4 Conclusions

1. Developed a model where firms trade productive activities, rather than final goods.

2. If low-skilled labor is cheap abroad, it is efficient for a domestic company to offshore activities that are intensive in low-skilled labor. Offshoring should raise the relative wage of skilled labor in both countries.

3. There are usually overall gains from offshoring. However, if offshoring causes a deterioration of the terms of trade then the gains from offshoring will be smaller.

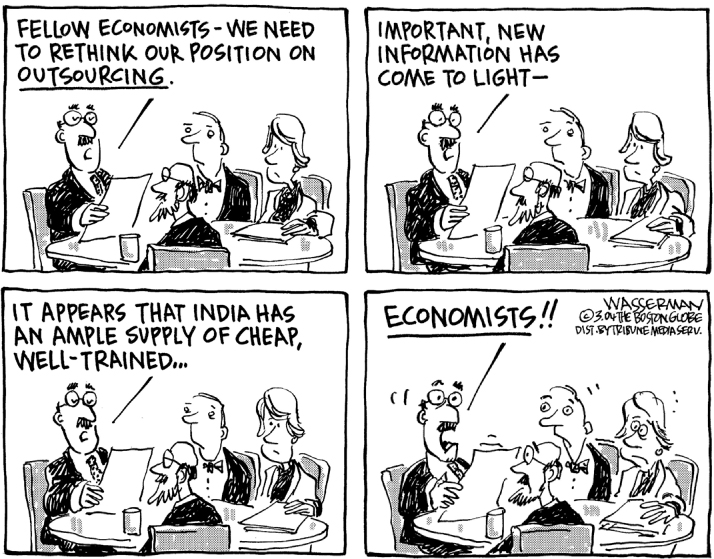

4. The U.S. offshoring to Mexico is mostly of low-skilled labor. The U.S. offshoring to India is mostly of high-skilled labor, providing services that might compete with U.S. services. Nonetheless, the U.S. still has a comparative advantage in most business services. India may become a competitive threat in some of these provisions, but others must be provided locally, and cannot be offshored.

In this chapter, we have studied a type of trade that is becoming increasingly important: offshoring, by which we mean the shifting of some production activities to another country, while other production activities are kept at Home. Rather than trading final goods, like wheat for cloth as in the Ricardian model of Chapter 2, or computers for shoes as in the Heckscher-Ohlin model of Chapter 4, with offshoring each good can be produced in stages in several countries and then assembled in a final location.

227

In the model of offshoring we presented, because low-skilled labor is relatively cheap abroad, it makes sense for Home to offshore to the Foreign country those activities that are less skill-intensive, while keeping at Home those activities that are more skill-intensive. “Slicing” the value chain in this way is consistent with the idea of comparative advantage, because each country is engaged in the activities for which its labor is relatively cheaper. From both the Home and Foreign point of view, the ratio of high-skilled/low-skilled labor in value chain activities goes up. A major finding of this chapter, then, is that an increase in offshoring will raise the relative demand (and hence relative wage) for skilled labor in both countries.

In a simplified model in which there are only two activities, we found that a fall in the world price of the low-skilled and labor-intensive input will lead to gains to the Home firm from offshoring. But in contrast, a fall in the price of the skilled labor-intensive input would lead to losses to the Home firm, as compared with the prior trade equilibrium. Such a price change is a terms-of-trade loss for Home, leading to losses from the lower relative price of exports. So even though Home gains overall from offshoring (producing at least as much as it would in a no-offshoring equilibrium), it is still the case that competition in the input being exported by Home will make it worse off.

We concluded the chapter by exploring offshoring in service activities, a topic that has received much attention in the media recently. Offshoring from the United States to Mexico consists mainly of low-skilled jobs; offshoring from the United States to India consists of higher-skilled jobs performed by college-educated Indians. This new type of offshoring has been made possible by information and communication technologies (such as the Internet and fiber-optic cables) and has allowed cities like Bangalore, India, to establish service centers for U.S. companies. These facilities not only answer questions from customers in the United States and worldwide, they are also engaged in accounting and finance, writing software, R&D, and many other skilled business services.

The fact that it is not only possible to shift these activities to India but economical to do so shows how new technologies make possible patterns of international trade that would have been unimaginable a decade ago. Such changes show “globalization” at work. Does the offshoring of service activities pose any threat to white-collar workers in the United States? There is no simple answer. On the one hand, we presented evidence that service offshoring provides productivity gains, and therefore gains from trade, to the United States. But as always, having gains from trade does not mean that everyone gains: there can be winners and losers. For service offshoring, it is possible that skilled workers will see a potential reduction in their wages, just as low-skilled labor bore the brunt of the impact from offshoring in the 1980s. Nevertheless, it is still the case that the United States, like the United Kingdom and other European countries, continues to have a comparative advantage in exporting various types of business services. Although India is making rapid progress in the area of computer and information services, there are still many types of service activities that need be done locally and cannot be outsourced. One likely prediction is that the activities in the United States that cannot be codified in written rules and procedures, and that benefit from face-to-face contact as well as proximity to other highly skilled individuals in related industries, will continue to have comparative advantage.

228