5 Fixed Exchange Rates and the Trilemma

Adapting the model to fixed rates1. What Is a Fixed Exchange Rate Regime?

In a fixed exchange rate regime, the central bank buys and sells foreign currency to achieve a desired, fixed level. Assume capital mobility. To be concrete, use the example of Denmark pegging the krone to the euro.

2. Pegging Sacrifices Monetary Policy Autonomy in the Short Run: Example

Under fixed rates, the expected rate of depreciation is zero, so the Danish interest rate must equal the European interest rate. It completely loses control of its monetary policy. In fact, it loses control of its money supply too: If Denmark were to increase its money supply, its interest rate would start to fall. But this would cause a massive capital outflow that would tend to make the krone depreciation. To maintain the peg, the Danish central bank would have to raise interest rates, which would entail decreasing the money supply. The short-run model still applies, but with causality reversed: Under a float, the money supply is exogenous and the exchange rate is endogenous. Under fixed rates, the exchange rate is exogenous and the money supply is endogenous.

3. Pegging Sacrifices Monetary Policy Autonomy in the Long Run: Example

PPP implies that in the long run Danish prices will be a fixed multiple of European prices.The long-run model still applies, but with causality reversed. Under a float, the money supply is exogenous and prices and the exchange rate are endogenous. Under fixed rate, the exchange rate is exogenous and the money supply is endogenous.

4. The Trilemma

Consider policy choices about exchange rate regime, the degree of capital mobility, and autonomy of monetary policy. Choosing any two determines the third. Example: Fixing the exchange rate and maintaining capital mobility implies the loss of monetary policy.

We have developed a complete theory of exchange rates, based on the assumption that market forces in the money market and the foreign exchange market determine exchange rates. Our models have the most obvious application to the case of floating exchange rate regimes. But as we have seen, not every country floats. Can our theory also be applied to the equally important case of fixed exchange rate regimes and to other intermediate regimes? The answer is yes, and we conclude this chapter by adapting our existing theory for the case of fixed regimes.

What Is a Fixed Exchange Rate Regime?

To understand the crucial difference between fixing and floating, we contrast the polar cases of tight fixing (hard pegs including narrow bands) and free floating, and ignore, for now, intermediate regimes. We also set aside regimes that include controls on arbitrage (capital controls) because such extremes of government intervention render our theory superfluous. Instead, we focus on the case of a fixed rate regime without controls so that capital is mobile and arbitrage is free to operate in the foreign exchange market.

Here the government itself becomes an actor in the foreign exchange market and uses intervention in the market to influence the market rate. Exchange rate intervention takes the form of the central bank buying and selling foreign currency at a fixed price, thus holding the market exchange rate at a fixed level denoted  .

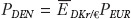

.

We can explore the implications of that policy in the short run and the long run using the familiar building blocks of our theory. To give a concrete flavor to these analyses, we replace the United States and the Eurozone (whose currencies float against each other) with an example of an actual fixed exchange rate regime. In this example, Foreign remains the Eurozone, but Home is now Denmark.

We examine the implications of Denmark’s decision to peg its currency, the krone, to the euro at a fixed rate  .4

.4

In the long run, fixing the exchange rate is one kind of nominal anchor. Yet even if it allowed the krone to float but had some nominal anchor, Denmark’s monetary policy would still be constrained in the long run by the need to achieve its chosen nominal target. We have seen that any country with a nominal anchor faces long-run monetary policy constraints of some kind. What we now show is that a country with a fixed exchange rate faces monetary policy constraints not just in the long run but also in the short run.

Pegging Sacrifices Monetary Policy Autonomy in the Short Run: Example

By assumption, equilibrium in the krone–euro forex market requires that the Danish interest rate be equal to the Eurozone interest rate plus the expected rate of depreciation of the krone. But under a peg, the expected rate of depreciation is zero.

142

Here uncovered interest parity reduces to the simple condition that the Danish central bank must set its interest rate equal to i€, the rate set by the ECB:

This is a very clear way of making a vital point: capital mobility + fixed rates -> loss of monetary independence.

Denmark has lost control of its monetary policy: it cannot independently change its interest rate under a peg.

The same is true of money supply policy. Short-run equilibrium in Denmark’s money market requires that money supply equal money demand, but once Denmark’s interest rate is set equal to the Eurozone interest rate i€, there is only one feasible level for money supply, as we see by imposing i€ as the Danish interest rate in money market equilibrium:

The implications are striking. The final expression contains the euro interest rate (exogenous, as far as the Danes are concerned), the fixed price level (exogenous by assumption), and output (also exogenous by assumption). No variable in this expression is under the control of the Danish authorities in the short run, and this is the only level of the Danish money supply consistent with equilibrium in the money and forex markets at the pegged rate  . If the Danish central bank is to maintain the peg, then in the short run it must choose the level of money supply implied by the last equation.

. If the Danish central bank is to maintain the peg, then in the short run it must choose the level of money supply implied by the last equation.

What’s going on? Arbitrage is the key force. For example, if the Danish central bank tried to supply more krone and lower interest rates, they would be foiled by arbitrage. Danes would want to sell krone deposits and buy higher-yield euro deposits, applying downward pressure on the krone. To maintain the peg, whatever krone the Danish central bank had tried to pump into circulation, it would promptly have to buy them back in the foreign exchange market.

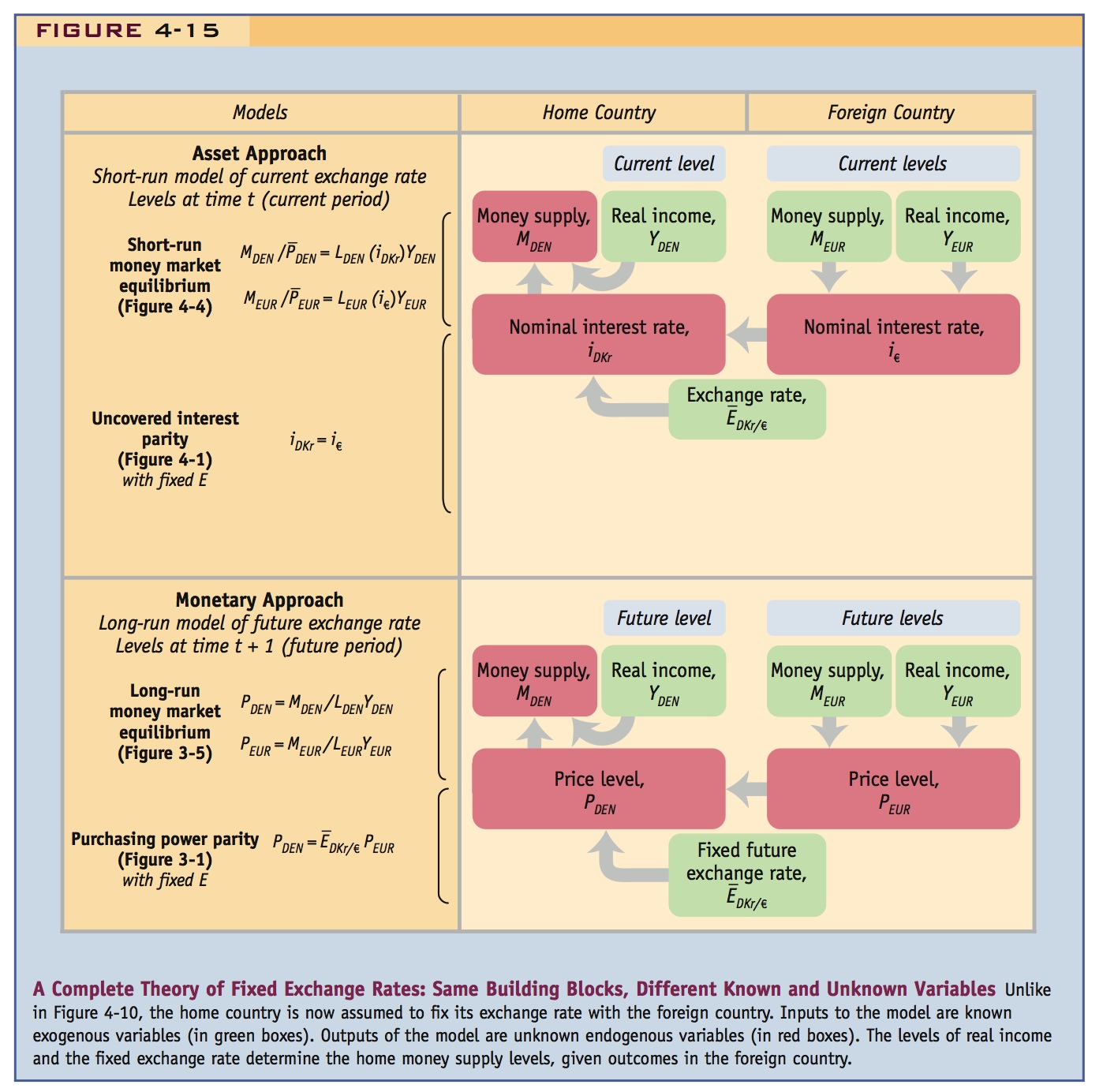

Thus, our short-run theory still applies, but with a different chain of causality:

A nicely symmetric way of comparing the structure of the model under fixed and flexible rates: Under fixed rates E is exogenous and M is endogenous; under flexible rates E is endogenous and M is exogenous.

- Under a float, the home monetary authorities pick the money supply M. In the short run, the choice of M determines the interest rate i in the money market; in turn, via UIP, the level of i determines the exchange rate E. The money supply is an input in the model (an exogenous variable), and the exchange rate is an output of the model (an endogenous variable).

- Under a fix, this logic is reversed. Home monetary authorities pick the fixed level of the exchange rate E. In the short run, a fixed E pins down the home interest rate i via UIP (forcing i to equal the foreign interest rate i*); in turn, the level of i determines the level of the money supply M necessary to meet money demand. The exchange rate is an input in the model (an exogenous variable), and the money supply is an output of the model (an endogenous variable).

This reversal of short-run causality is shown in a new schematic in the top part of Figure 4-15.

143

Pegging Sacrifices Monetary Policy Autonomy in the Long Run: Example

As we have noted, choosing a nominal anchor implies a loss of long-run monetary policy autonomy. Let’s quickly see how that works when the anchor is a fixed exchange rate.

Following our discussion of the standard monetary model, we must first ask what the nominal interest rate is going to be in Denmark in the long run. But we have already answered that question; it is going to be tied down the same way as in the short run, at the level set by the ECB, namely i€. We might question, in turn, where that level i€ comes from (the answer is that it will be related to the “neutral” level of the nominal interest rate consistent with the ECB’s own nominal anchor, its inflation target for the Eurozone). But that is beside the point: all that matters is that i€ is as much out of Denmark’s control in the long run as it is in the short run.

144

Next we turn to the price level in Denmark, which is determined in the long run by PPP. But if the exchange rate is pegged, we can write long-run PPP for Denmark as

Conclude that fixed rates provide an effective nominal anchor to prevent inflation.

Here we encounter another variable that is totally outside of Danish control in the long run. Under PPP, pegging to the euro means that the Danish price level is a fixed multiple of the Eurozone price level (which is exogenous, as far as the Danes are concerned).

With the long-run nominal interest and price level outside of Danish control, we can show, as before, that monetary policy autonomy is out of the question. We just substitute iDKr = i€ and  into Denmark’s long-run money market equilibrium to obtain

into Denmark’s long-run money market equilibrium to obtain

The final expression contains the long-run euro interest rate and price levels (exogenous, as far as the Danes are concerned), the fixed exchange rate level (exogenous by assumption), and long-run Danish output (also exogenous by assumption). Again, no variable in the final expression is under the control of the Danish authorities in the long run, and this is the only level of the Danish money supply consistent with equilibrium in the money and foreign exchange market at the pegged rate of  .

.

Thus, our long-run theory still applies, just with a different chain of causality:

- Under a float, the home monetary authorities pick the money supply M. In the long run, the growth rate of M determines the interest rate i via the Fisher effect and also the price level P; in turn, via PPP, the level of P determines the exchange rate E. The money supply is an input in the model (an exogenous variable), and the exchange rate is an output of the model (an endogenous variable).

- Under a fix, this logic is reversed. Home monetary authorities pick the exchange rate E. In the long run, the choice of E determines the price level P via PPP, and also the interest rate i via UIP; these, in turn, determine the necessary level of the money supply M. The exchange rate is an input in the model (an exogenous variable), and the money supply is an output of the model (an endogenous variable).

Explain that in the long run P is endogenous under flexible rates, but exogenous under fixed rates (because of PPP).

This reversal of long-run causality is also shown in the new schematic in the bottom part of Figure 4-15.

The Trilemma

Our findings lead to the conclusion that policy makers face some tough choices. Not all desirable policy goals can be simultaneously met. These constraints are summed up in one of the most important principles in open-economy macroeconomics.

145

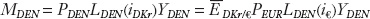

Consider the following three equations and parallel statements about desirable policy goals. For illustration we return to the Denmark–Eurozone example:

This is so essential that you should spend some time on this. Make sure they understand each of the three steps in the argument. Have them contemplate the triangle in Figure 4-16. Think of extreme examples: U.S. (capital mobility+ float = monetary autonomy); Hong Kong (capital mobility + fixed rates = no monetary autonomy); China (capital controls + fixed rate (sort of) = monetary autonomy). Then consider the intermediate cases below.

For a variety of reasons, as noted, governments may want to pursue all three of these policy goals. But they can’t: formulae 1, 2, and 3 show that it is a mathematical impossibility as shown by the following statements:

- 1 and 2 imply not 3 (1 and 2 imply interest equality, contradicting 3).

- 2 and 3 imply not 1 (2 and 3 imply an expected change in E, contradicting 1).

- 3 and 1 imply not 2 (3 and 1 imply a difference between domestic and foreign returns, contradicting 2).

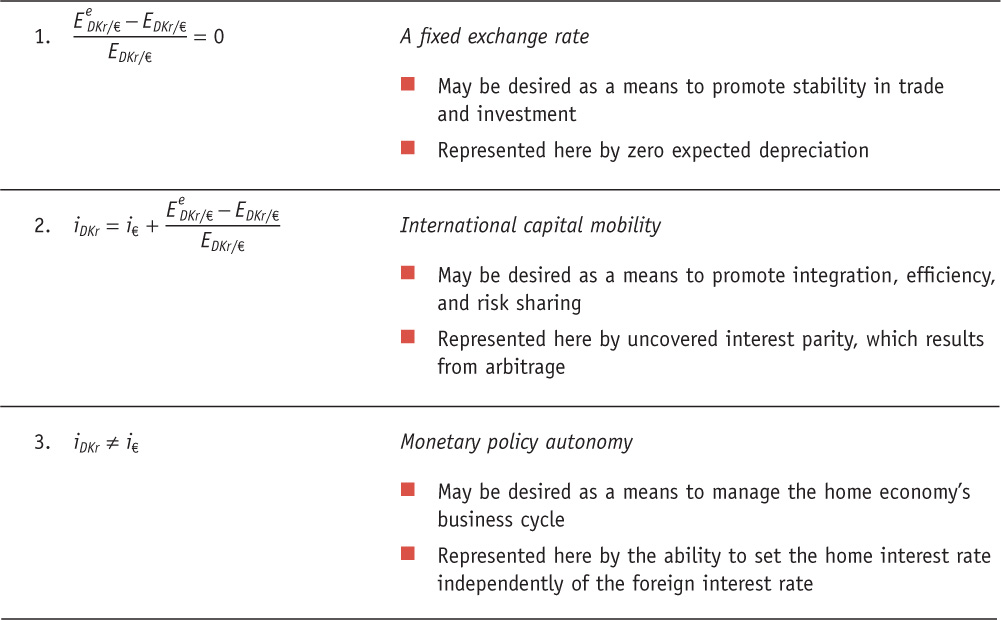

This result, known as the trilemma, is one of the most important ideas in international macroeconomics.5 It tells us that the three policy goals just outlined are mutually incompatible: you cannot have all three at once. You must choose to drop one of the three (or, equivalently, you must adopt one of three pairs: 1 and 2, 2 and 3, or 3 and 1). Sadly, there is a long history of macroeconomic disasters stemming from the failure of some policy that ignored this fundamental lesson.

The trilemma can be illustrated graphically as in Figure 4-16. Each corner of the triangle represents a viable policy regime choice. For each corner, the label on the opposite edge of the triangle indicates the goal that has been sacrificed, while the labels on the two adjacent edges show the two goals that can be attained under that choice (see Side Bar: Intermediate Regimes).

146

Allowing for capital controls or abandoning a hard peg permits some control of monetary policy.

Intermediate Regimes

The lessons of the trilemma most clearly apply when the policies are at the ends of a spectrum: a hard peg or a float, perfect capital mobility or immobility, complete autonomy or none at all. But sometimes a country may not be fully in one of the three corners: the rigidity of the peg, the degree of capital mobility, and the independence of monetary policy could be partial rather than full.

For example, in a band arrangement, the exchange rate is maintained within a range of ±X% of some central rate. The significance of the band is that some expected depreciation (i.e., a little bit of floating) is possible. As a result, a limited interest differential can open up between the two countries. For example, suppose the band is 2% wide (i.e., ±1% around a central rate). To compute home interest rates, UIP tells us that we must add the foreign interest rate (let’s suppose it is 5%) to the expected rate of depreciation (which is ±2% if the exchange rate moves from one band edge to the other). Thus, Home may “fix” this way and still have the freedom to set 12-month interest rates in the range between 3% and 7%. But the home country cannot evade the trilemma forever: on average, over time, the rate of depreciation will have to be zero to keep the exchange rate within the narrow band, meaning that the home interest rate must track the foreign interest rate apart from small deviations.

Similar qualifications to the trilemma could result from partial capital mobility, in which barriers to arbitrage could also lead to interest differentials. And with such differentials emerging, the desire for partial monetary autonomy can be accommodated.

In practice, once these distinctions are understood, it is usually possible to make some kind of judgment about which corner best describes the country’s policy choice. For example, in 2007 both Slovakia and Denmark were supposedly pegged to the euro as members of the EU’s Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). But the similarities ended there. The Danish krone was operating in ERM bands of official width ±2.25%, but closer to ±0.5% in practice, a pretty hard peg with almost no movement. The Slovak koruna was operating with ±15% bands and at one point even shifted that band by appreciating its central rate by 8.5% in March 2007. With its perpetual narrow band, Denmark’s regime was clearly fixed. With its wide and adjustable bands, Slovakia’s regime was closer to managed floating.*

* Note that Slovakia has since joined the euro as of 2009.

147

Denmark has pegged to the euro and maintained capital mobility, so it has lost its monetary policy. The UK has flexible rates and kept capital mobility, so it does have an independent monetary policy.

The Trilemma in Europe

We motivated the trilemma with the case of Denmark, which has chosen policy goals 1 and 2. As a member of the European Union (EU), Denmark adheres to the single-market legislation that requires free movement of capital within the bloc. It also unilaterally pegs its krone to the euro under the EU’s Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), an arrangement that ostensibly serves as a stepping-stone to Eurozone membership. Consequently, UIP predicts that the Danish central bank must set an interest rate at the same level as that set by the ECB; it has lost option 3.

The Danes could make one of two politically difficult choices if they wished to gain monetary independence from the ECB: they could abandon their commitment to the EU treaties on capital mobility (drop 2 to get 3), which is extremely unlikely, or they could abandon their ERM commitment and let the krone float against the euro (drop 1 to get 3), which is also fairly unlikely. Floating is, however, the choice of the United Kingdom, an EU country that has withdrawn from the ERM and that allows the pound to float against the euro.

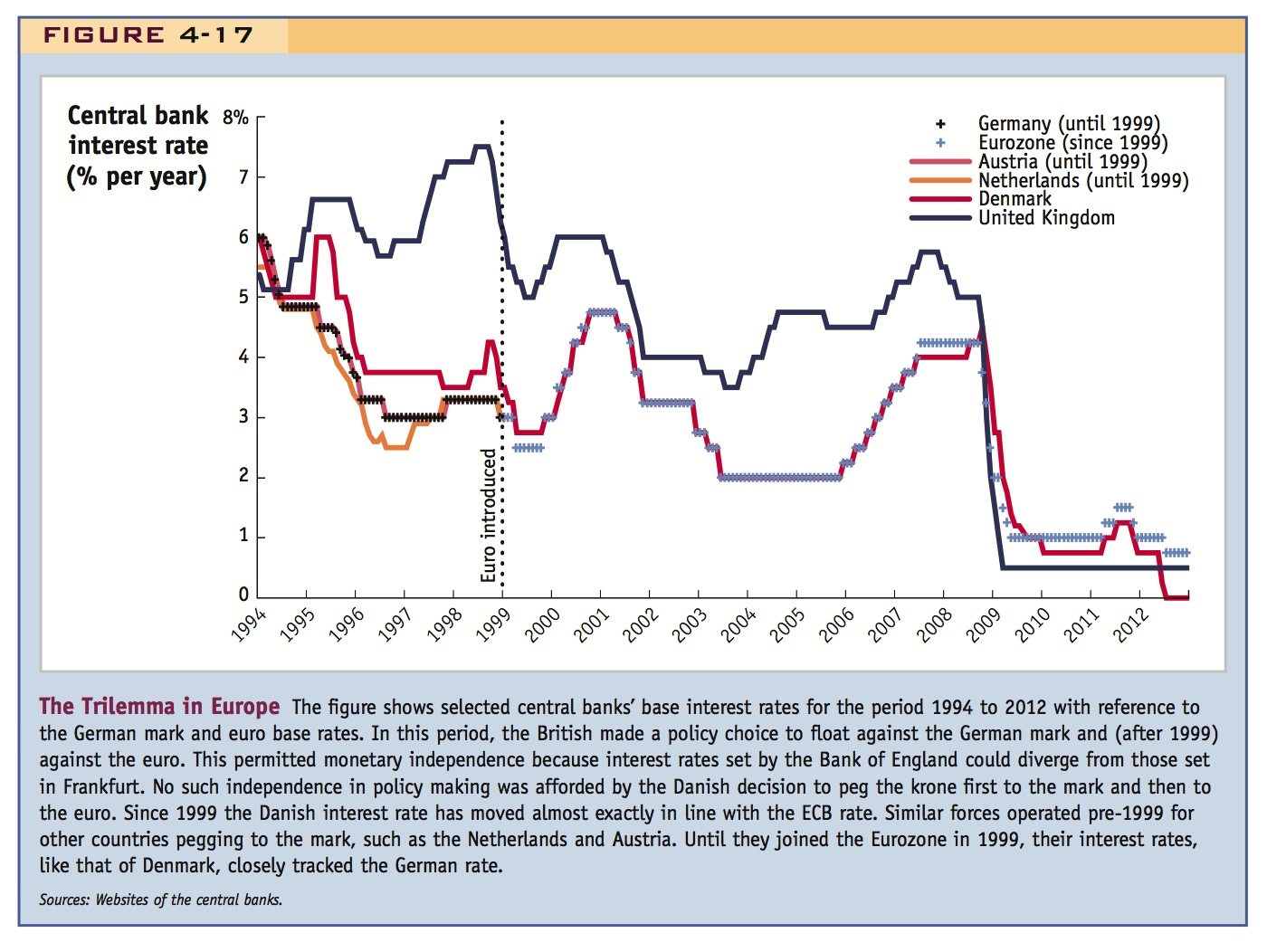

Figure 4-17 shows evidence for the trilemma. Since 1999 the United Kingdom has had the ability to set interest rates independently of the ECB. But Denmark has not: since 1999 the Danish interest rate has tracked the ECB’s rate almost exactly. (Most of the departures from equality reflect uncertainty about the euro project and Denmark’s peg at two key moments: at the very start of the euro project in 1999, and during the credibility crisis of the Eurozone since the crisis of 2008.)

148

These monetary policy ties to Frankfurt even predate the euro itself. Before 1999 Denmark, and some countries such as Austria and the Netherlands, pegged to the German mark with the same result: their interest rates had to track the German interest rate, but the U.K. interest rate did not. The big difference is that Austria and the Netherlands have formally abolished their national currencies, the schilling and the guilder, and have adopted the euro—an extreme and explicit renunciation of monetary independence. Meanwhile, the Danish krone lives on, showing that a national currency can suggest monetary sovereignty in theory but may deliver nothing of the sort in practice.