6 Conclusions

1. This chapter developed the asset approach to short-run exchange rate determination. It then integrated this short-run model with the long-run monetary approach to develop a unified theory of exchange rates.

2. Ensuing chapters will apply these theories to explain how exchange rates affect the rest of the macroeconomy.

3. The theory has worked well, and is commonly used by economists and policymakers.

In this chapter, we drew together everything we have learned so far about exchange rates. We built on the concepts of arbitrage and equilibrium in the foreign exchange market in the short run, taking expectations as given and applying uncovered interest parity. We also relied on the purchasing power parity theory as a guide to exchange rate determination in the long run. Putting together all these building blocks provides a complete and internally consistent theory of exchange rate determination.

Exchange rates are an interesting topic in and of themselves, but at the end of the day, we also care about what they mean for the wider economy, how they relate to macroeconomic performance, and the part they play in the global monetary system. That is our goal in the next chapters in which we apply our exchange rate theories in a wider framework to help us understand how exchange rates function in the national and international economy.

Both are neat examples that students will find interesting.

The theory we’ve developed in the past three chapters is the first tool that economists and policy makers pick up when studying a problem involving exchange rates. This theory has served well in rich and poor countries, whether in periods of economic stability or turbulence. Remarkably, it has even been applied in wartime, and to round off our discussion of exchange rates, we examine some colorful applications of the theory from conflicts past and present.

Applies the model to explain exchange rate behavior during the Civil War and the Second Iraq War.

News and the Foreign Exchange Market in Wartime

Our theory of exchange rates places expectations at center stage, but demonstrating the effect of changing expectations empirically is a challenge. However, wars dramatically expose the power of expectations to change exchange rates. War raises the risk that a currency may depreciate in value rapidly in the future, possibly all the way to zero. For one thing, the government may need to print money to finance its war effort, but how much inflation this practice will generate may be unclear. In addition, there is a risk of defeat and a decision by the victor to impose new economic arrangements such as a new currency; the existing currency may then be converted into the new currency at a rate dictated by the victors or, in a worst-case scenario, it may be declared totally worthless, that is, not legal tender. Demand for the currency will then collapse to nothing and so will its value. Investors in the foreign exchange market are continually updating their forecasts about a war’s possible outcomes, and, as a result, the path of an exchange rate during wartime usually reveals a clear influence of the effects of news.

149

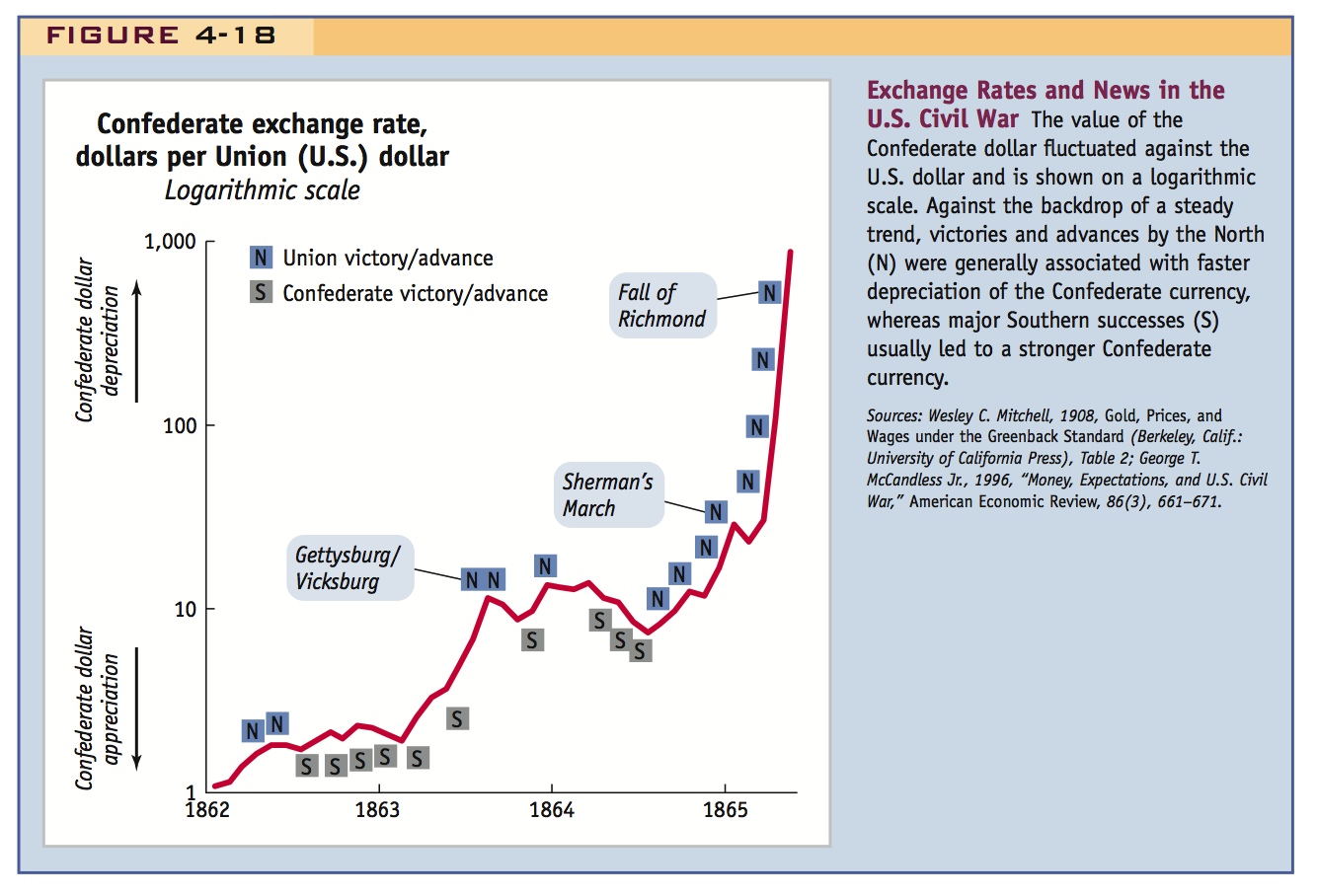

The U.S. Civil War, 1861–1865 For four years, beginning April 12, 1861, a war raged between Union (Northern) and Confederate (Southern) forces. An important economic dimension of this conflict was the decision by the Confederate states to issue their own currency, the Confederate dollar, to help gain economic autonomy from the North and finance their war effort. The exchange rate of the Confederate dollar against the U.S. dollar is shown in Figure 4-18.

How should we interpret these data? The two currencies differed in one important respect. If the South had won, and the Confederate states had gained independence, they would have kept their Confederate dollar, and the Northern United States would have kept their U.S. dollar, too. Instead, the South was defeated, and, as expected in these circumstances, the U.S. dollar was imposed as the sole currency of the unified country; the Confederate dollar, like all liabilities of the Confederate nation, was repudiated by the victors and, hence, became worthless.

150

War news regularly influenced the exchange rate.6 As the South headed for defeat, the value of the Confederate dollar shrank. The overall trend was driven partly by inflationary war finance and partly by the probability of defeat. Major Northern victories marked “N” tended to coincide with depreciations of the Confederate dollar. Major Southern victories marked “S” were associated with appreciations or, at least, a slower depreciation. The key Union victory at Gettysburg, July 1–3, 1863, and the near simultaneous fall of Vicksburg on July 4 were followed by a dramatic depreciation of the Confederate dollar. By contrast, Southern victories (in the winter of 1862 to 1863 and the spring of 1864) were periods when the Southern currency held steady or even appreciated. But by the fall of 1864, and particularly after Sherman’s March, the writing was on the wall, and the Confederate dollar began its final decline.

Currency traders in New York did good business either way. They were known to whistle “John Brown’s Body” after a Union victory and “Dixie” after Confederate success, making profits as they traded dollars for gold and vice versa. Abraham Lincoln was not impressed, declaring, “What do you think of those fellows in Wall Street, who are gambling in gold at such a time as this?…For my part, I wish every one of them had his devilish head shot off.”

The Iraq War, 2002–2003 The Civil War is not the only example of such phenomena. In 2003 Iraq was invaded by a U.S.-led coalition of forces intent on overthrowing the regime of Saddam Hussein, and the effects of war on currencies were again visible.7

Our analysis of this case is made a little more complicated by the fact that at the time of the invasion there were two currencies in Iraq. Indeed, some might say there were two Iraqs. Following a 1991 war, Iraq had been divided: in the North, a de facto Kurdish government was protected by a no-fly zone enforced by the Royal Air Force and U.S. Air Force; in the South, Saddam’s regime continued. The two regions developed into two distinct economies, and each had its own currency. In the North, Iraqi dinar notes called “Swiss” dinars circulated.8 In the South, a new currency, the “Saddam” or “print” dinar, was introduced.9

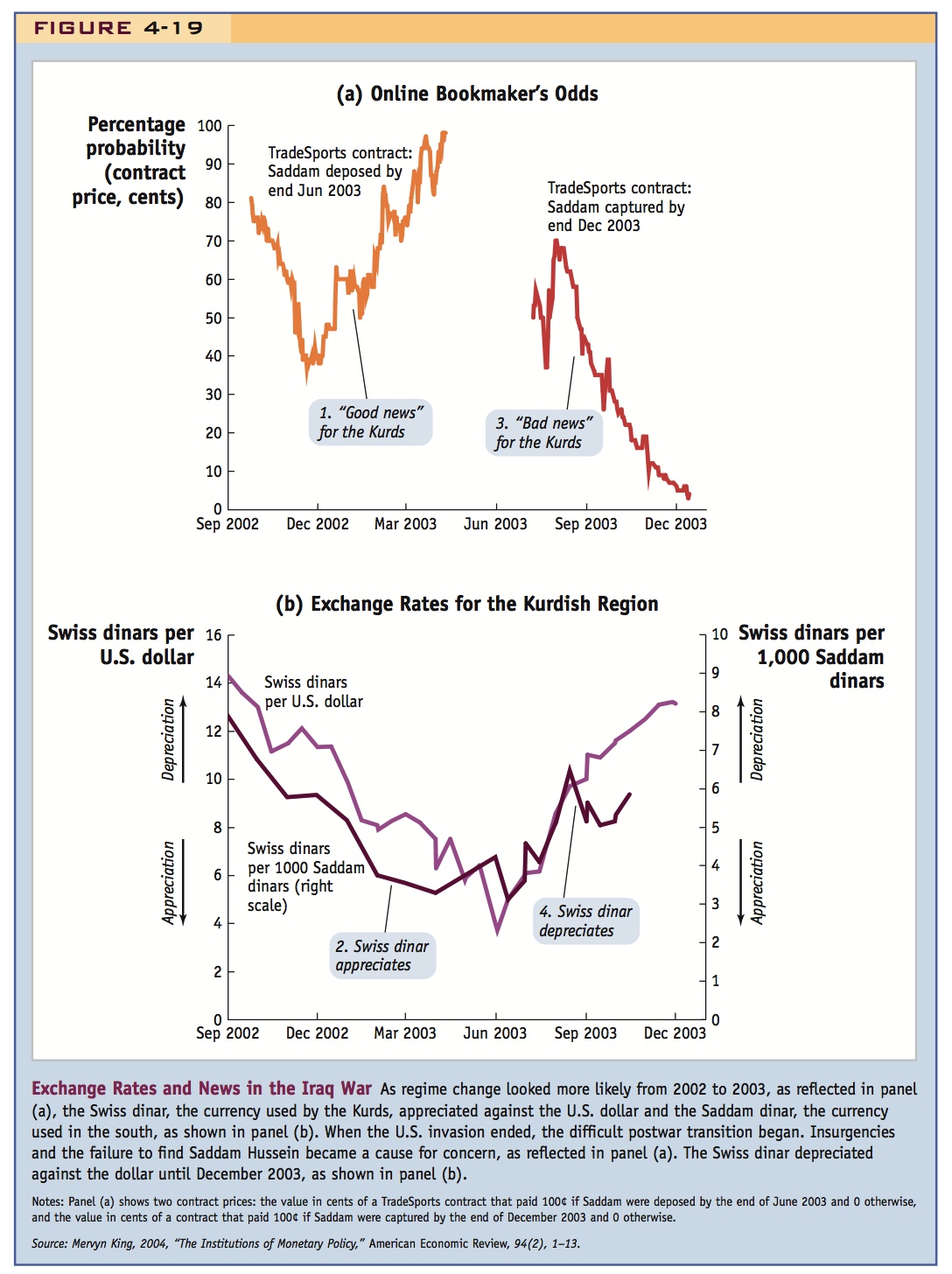

Figure 4-19 shows the close correlation between wartime news and exchange rate movements for this modern episode. We can compare exchange rate movements with well-known events, but panel (a) allows another interesting comparison. In 2002 a company called TradeSports Exchange allowed bets on Saddam’s destiny by setting up a market in contracts that paid $1 if he was deposed by a certain date, and the prices of these contracts are shown using the left scale. After he was deposed, contracts that paid out upon his capture were traded, and these are also shown. If such a contract had a price of, say, 80¢, then this implied that “the market” believed the probability of overthrow or apprehension was 80%.

151

152

In panel (b), we see the exchange rates of the Swiss dinar against the U.S. dollar and the Saddam dinar from 2002 to 2003. The Kurds’ Swiss dinar–U.S. dollar rate had held at 18 per U.S. dollar for several years but steadily appreciated in 2002 and 2003 as the prospect of a war to depose Saddam became more likely. By May 2003, when the invasion phase of the war ended and Saddam had been deposed, it had appreciated as far as 6 to the dollar. The war clearly drove this trend: the more likely the removal of Saddam, the more durable would be Kurdish autonomy, and the more likely it was that a postwar currency would be created that respected the value of the Kurds’ Swiss dinars. Notice how the rise in the value of the Swiss dinar tracked the odds of regime change until mid-2003.

After Baghdad fell, the coalition sought to capture Saddam, who had gone into hiding. As the hunt wore on, and a militant/terrorist insurgency began, fears mounted that he would never be found and his regime might survive underground and reappear. The odds on capture fell, and, moving in parallel, so did the value of the Swiss dinar. The Kurds now faced a rising probability that the whole affair would end badly for them and their currency. (However, when Saddam Hussein was captured on December 14, 2003, the Swiss dinar appreciated again.)

We can also track related movements in the Swiss dinar against the Saddam or print dinar. Before and during the war, while the Swiss dinar was appreciating against the U.S. dollar, it was also appreciating against the Saddam dinar. It strengthened from around 10 Swiss dinars per 1,000 Saddam dinars in early 2002 to about 3 Swiss dinars per 1,000 Saddam dinars in mid-2003. Then, as the postwar operations dragged on, this trend was reversed. By late 2003, the market rate was about 6 Swiss dinars per 1,000 Saddam dinars. Again, we can see how the Kurds’ fortunes appeared to the market to rise and fall.

What became of all these dinars? Iraqis fared better than the holders of Confederate dollars. A new dinar was created under a currency reform announced in July 2003 and implemented from October 15, 2003, to January 15, 2004.10 Exchange rate expectations soon moved into line with the increasingly credible official conversion rates and U.S. dollar exchange rates for the new dinar.

153