1 Measuring Macroeconomic Activity: An Overview

Review of the circular flow of payments and the national income and product accounts for a closed economy. Then introduce cross-border flows with the balance of payments.

1. The Flow of Payments in a Closed Economy: Introducing the National Income and Product Accounts

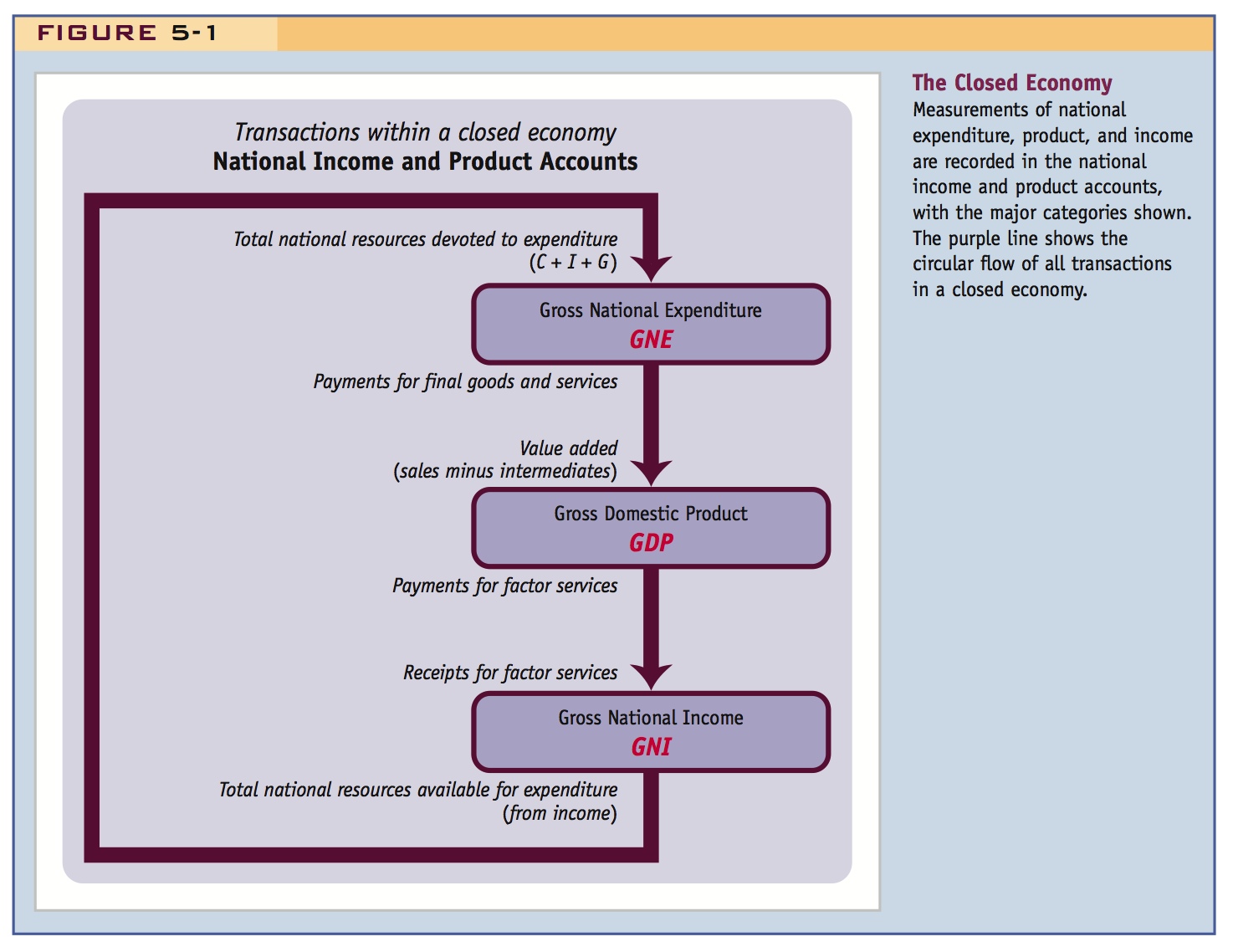

Review of gross national expenditures (GNE ≡ C + I + G), gross domestic product (GDP), and gross national income (GNI) in a closed economy. For the closed economy, GNE = GDP = GNI.

2. The Flow of Payments in an Open Economy: Incorporating the Balance of Payments Accounts

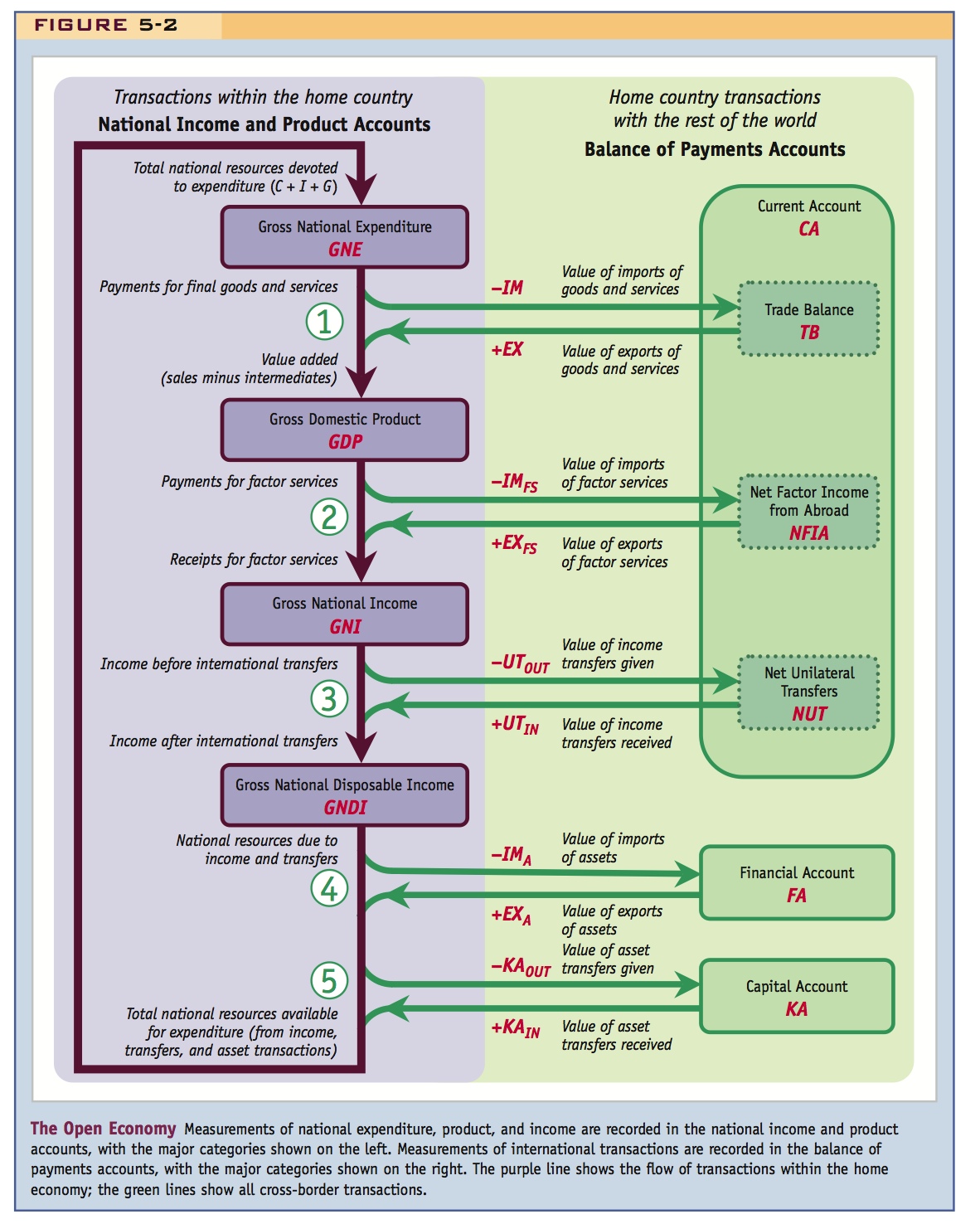

Trade creates new flows to and from the economy, measured in the balance of payments (BOP). New flows: (1) Exports and imports of goods and services, so GNE = C + I + G + TB. (2) Income must be adjusted for net factor income from abroad (NFIA), so GNI = GDP + NFIA. (3) Income must also be adjusted for net unilateral transfers (NUT), so gross national disposable income is GNDI = GNI + NUT. In the BOP the current account is CA = TB + NFIA + NUT, which summarizes flows of goods, services, and income.

Trading of financial assets is measured in the financial account (FA). Transfers of assets are measured in the capital account (KA), and are added to GNDI to calculate total resources available the economy.

The BOP ≡ 0.

To understand macroeconomic accounting in an open economy, we build on the principles used to track payments in a closed economy. As you may recall from previous courses in economics, a closed economy is characterized by a circular flow of payments, in which economic resources are exchanged for payments as they move through the economy. At various points in this flow, economic activity is measured and recorded in the national income and product accounts. In an open economy, however, such measurements are more complicated because we have to account for cross-border flows. These additional flows are recorded in a nation’s balance of payments accounts. In this opening section, we survey the principles behind these measurements. In later sections, we define the measurements more precisely and explore how they work in practice.

The Flow of Payments in a Closed Economy: Introducing the National Income and Product Accounts

Students should be familiar with the circular flow diagram, so you can go through this quickly.

Figure 5-1 shows how payments flow in a closed economy. At the top is gross national expenditure (GNE), the total expenditure on final goods and services by home entities in any given period of measurement (usually a calendar year, unless otherwise noted). It is made up of three parts: personal consumption C, investment I, and government spending G. The sum of these variables equals GNE.

159

Once GNE is spent, where do the payments flow next? All of this spending constitutes all payments for final goods and services within the nation’s borders. Because the economy is closed, the nation’s expenditure must be spent on the final goods and services it produces. More specifically, a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is the value of all (intermediate and final) goods and services produced as output by firms, minus the value of all intermediate goods and services purchased as inputs by firms. (GDP is also known as value added.) GDP is a product measure, in contrast to GNE, which is an expenditure measure. In a closed economy, intermediate sales must equal intermediate purchases, so in GDP these two terms cancel out, leaving only the value of final goods and services produced, which equals the expenditure on final goods and services, or GNE. Thus, GDP equals GNE.

Once GDP is sold, where do the payments flow next? Because GDP measures the value of firm outputs minus the cost of firm inputs, this remaining flow is paid by firms as income to factors such as the owners of labor, capital, and land employed by the firms. The factors may, in turn, be owned by households, government, or firms, but such distinctions are not important. The key thing in a closed economy is that all such income is paid to domestic entities. It thus equals the total income resources of the economy, also known as gross national income (GNI). By this point in our circular flow, we can see that in a closed economy the expenditure on total goods and services GNE equals GDP, which is then paid as income to productive factors GNI.

160

Nonetheless, you will be surprised at how many students still don't grasp this assertion.

Once GNI is received by factors, where do the payments flow next? Clearly, there is no way for a closed economy to finance expenditure except out of its own income, so total income is, in turn, spent and must be the same as total expenditure. This is shown by the loop that flows back to the top of Figure 5-1. What we have seen in our tour around the circular flow is that in a closed economy, all the economic aggregate measures are equal: GNE equals GDP which equals GNI which equals GNE. In a closed economy, expenditure is the same as product, which is the same as income. Our understanding of the closed economy circular flow is complete.

The Flow of Payments in an Open Economy: Incorporating the Balance of Payments Accounts

This is unavoidably tedious, but try to make it as intuitive as possible.

The closed-economy circular flow shown in Figure 5-1 is simple and tidy. When a nation opens itself to trade with other nations, however, the flow becomes a good deal more complicated. Figure 5-2 incorporates all of the extra payment flows to and from the rest of the world, which are recorded in a nation’s balance of payments (BOP) accounts.

The circulating purple arrows on the left side of the figure are just as in the closed-economy case in Figure 5-1. These arrows flow within the purple box, which represents the home country, and do not cross the edge of that box, which represents the international border. The cross-border flows that occur in an open economy are represented by green arrows. There are five key points on the figure where these flows appear.

Say that expenditures must be adjusted for exports and imports so that GDP = C + I + G + TB is in an open economy. Students should remember this.

As before, we start at the top with the home economy’s gross national expenditure, C + I + G. In an open economy, some home expenditure is used to purchase foreign final goods and services. At point 1, these imports are subtracted from home GNE because those goods are not sold by domestic firms. In addition, some foreign expenditure is used to purchase final goods and services from home. These exports must be added to home GNE because those goods are sold by domestic firms. (A similar logic applies to intermediate goods.) The difference between payments made for imports and payments received for exports is called the trade balance (TB), and it equals net payments to domestic firms due to trade. GNE plus TB equals GDP, the total value of production in the home economy.

Give examples of income received from, or paid to, the ROW.

At point 2, some home GDP is paid to foreign entities for factor service imports, that is, domestic payments to capital, labor, and land owned by foreign entities. Because this income is not paid to factors at home, it is subtracted when computing home income. Similarly, some foreign GDP may be paid to domestic entities as payment for factor service exports, that is, foreign payments to capital, labor, and land owned by domestic entities. Because this income is paid to factors at home, it is added when computing home income. The value of factor service exports minus factor service imports is known as net factor income from abroad (NFIA). Thus GDP plus NFIA equals GNI, the total income earned by domestic entities from all sources, domestic and foreign.

Say that income must also be adjusted, by adding net factor income from abroad and a net unilateral transfers. Give examples of transfers.

At point 3, we see that the home country may not retain all of its earned income GNI. Why? Domestic entities might give some of it away—for example, as foreign aid or remittances by migrants to their families back home. Similarly, domestic entities might receive gifts from abroad. Such gifts may take the form of income transfers or be “in kind” transfers of goods and services. They are considered nonmarket transactions, and are referred to as unilateral transfers. Net unilateral transfers (NUT) equals the value of unilateral transfers the country receives from the rest of the world minus those it gives to the rest of the world. These net transfers are added to GNI to calculate gross national disposable income (GNDI). Thus GNI plus NUT equals GNDI, which represents the total income resources available to the home country.

161

162

CA is fundamental. Make sure students understand this interpretation.

The balance of payments accounts collect the trade balance, net factor income from abroad, and net unilateral transfers and report their sum as the current account (CA), a tally of all international transactions in goods, services, and income that occur through market transactions or transfers. The current account is not, however, a complete picture of international transactions. Resource flows of goods, services, and income are not the only items that flow between open economies. Financial assets such as stocks, bonds, or real estate are also traded across international borders.

Likewise for the FA. Beware: This is the IMF's terminology. For most everybody else, the "capital account" is equal to the sum of what the IMF calls the "financial account" and the "capital account." See footnote 1.

At point 4, we see that a country’s capacity to spend is not restricted to be equal to its GNDI, but instead can be increased or decreased by trading assets with other countries. When foreign entities pay to acquire assets from home entities, the value of these asset exports increases resources available for spending at home. Conversely, when domestic entities pay to acquire assets from the rest of the world, the value of the asset imports decreases resources available for spending. The value of asset exports minus asset imports is called the financial account (FA). These net asset exports are added to home GNDI when calculating the total resources available for expenditure in the home country.

Give examples of KA transactions, but add that they are relatively small and can be ignored in most of what we will be doing.

Finally, at point 5, we see that a country may not only buy and sell assets but also transfer assets as gifts. Such asset transfers are measured by the capital account (KA), which is the value of capital transfers from the rest of the world minus those to the rest of the world. These net asset transfers are also added to home GNDI when calculating the total resources available for expenditure in the home country.

After some effort, at the bottom of Figure 5-2, we have finally computed the total value of all the resources that are available for the home country to use for spending, or gross national expenditure, as the flow loops back to the top. We have now fully modified the circular flow to account for international transactions.1

These modifications to the circular flow in Figure 5-2 tell us something very important about the balance of payments. We start at the top with GNE. We add the trade balance to get GDP, we add net factor income from abroad to get GNI, and then we add net unilateral transfers received to get GNDI. We then add net asset exports measured by the financial account and net capital transfers measured by the capital account, and we get back to GNE. That is, we start with GNE, add in everything in the balance of payments accounts, and still end up with GNE. What does this tell us? The sum of all the items in the balance of payments account, the net sum of all those cross-border flows, must amount to zero! The balance of payments account does balance. We explore the implications of this important result later in this chapter.

163