Chapter Introduction

199

Balance of Payments I: The Gains from Financial Globalization

This chapter focuses on financial globalization. First it establishes the limits to borrowing imposed by a country's intertemporal budget constraint. Then it discusses the benefits from financial liberalization, namely consumption smoothing, and the gains from more efficient investment and from diversification.

- The Limits on How Much a Country Can Borrow: The Long-Run Budget Constraint

- Gains from Consumption Smoothing

- Gains from Efficient Investment

- Gains from Diversification of Risk

- Conclusions

Save for a rainy day.

Make hay while the sun shines.

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

1. Access to financial markets allows households to cope better with economic shocks by allowing them to borrow in time of need.

2. In the same way, access to international financial markets allows countries to cope better with economic shocks.

3. This chapter explains benefits of financial globalizationa. It surveys factors that inhibit international borrowing and lending

b. It argues that financial markets permit (1) consumption smoothing, (2) efficient investment, and (3) diversification of risk

c. It assesses the extent to which the theoretical benefits of financial globalization are actually realized. The gains are large for advanced countries, but for poor countries the gains are smaller, and harder to realize.

How does your household cope with economic shocks and the financial challenges they pose? Let’s take an extreme example. Suppose you are self-employed and own a business. A severe storm appears and a flood overwhelms your town. This is bad news on several fronts. As people recover from the disaster, businesses, including yours, suffer and your income is lower for several months. If your business premises are damaged, you must also plan to make new investments to repair the damage.

If you have no financial dealings with anyone, your household, as a little closed economy, faces a difficult trade-off as your income falls. Your household income has to equal its consumption plus investment. Would you try to maintain your level of consumption, and neglect the need to invest? Or would you invest, and let your household suffer as you cut back drastically on consumption? Faced with an emergency like this, most of us look for help beyond our own household, if we can: we might hope for transfers (gifts from friends and family, or emergency relief payments from the government or a charity), or we might rely on financial markets (dip into savings, apply for a loan, rely on an insurance payout, etc.).

What does this story have to do with international economics? If we redraw the boundaries of this experiment and expand from the household unit, to the local, regional, and finally national level, the same logic applies. Countries face shocks all the time, and how they are able cope with them depends on whether they are open or closed to economic interactions with other nations.

200

To get a sense of how countries can deal with shocks, we can look at data from Caribbean and Central American countries that have faced the same kinds of shock as the household we just described. Every year many tropical storms, some of them of hurricane strength, sweep through this region. The storms are large—hundreds of miles across—and most countries in the region are much smaller in size, some no more than little islets. For them, a hurricane is the town flood blown up to a national scale. The worst storms cause widespread destruction and loss of life.

Tell some preliminary stories now to explain why countries might want to borrow, since the next section will impose constraints on how it can be borrowed.

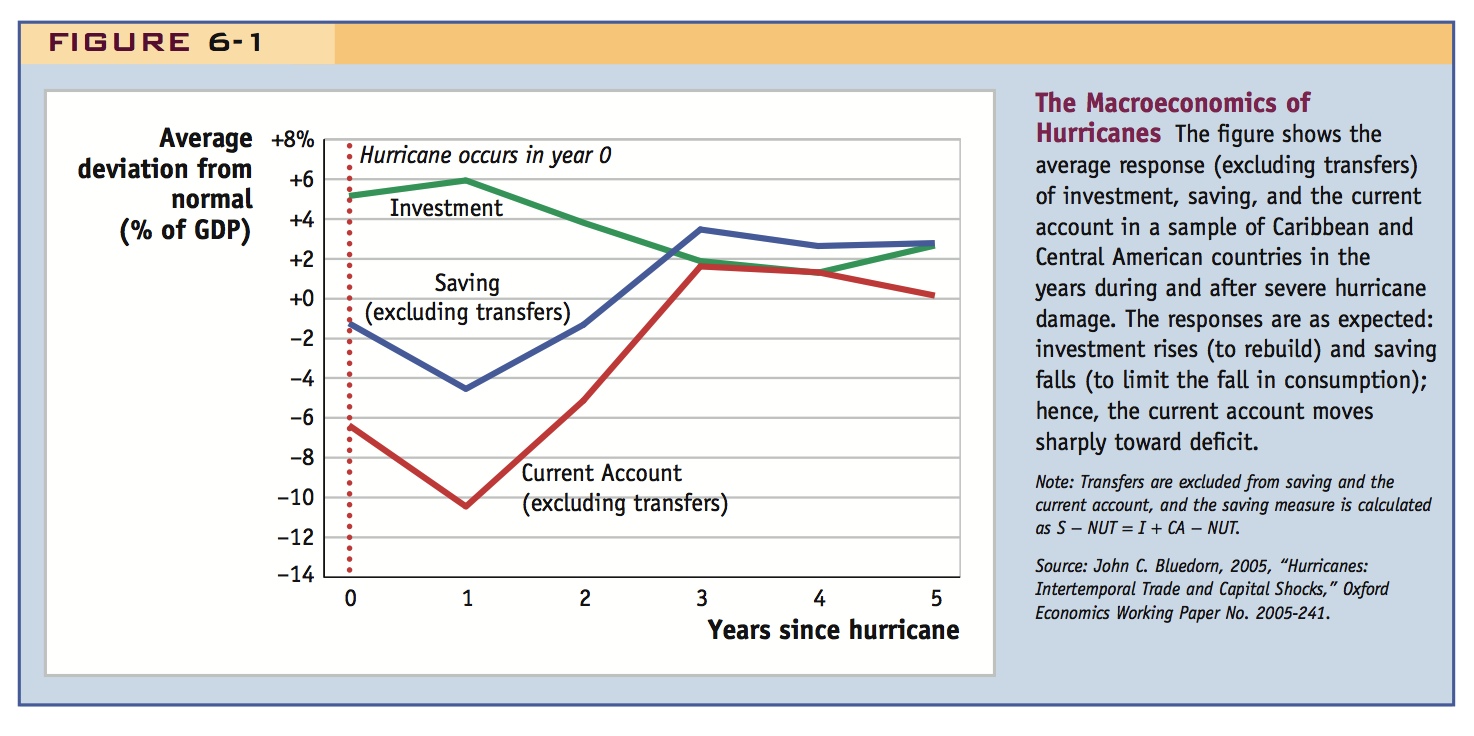

Hurricanes are tragic human events, but they provide an opportunity for research. Economists study them because such an “act of God”—in economics jargon, a “natural experiment”—provides a laboratory-like test of economic theory. Figure 6-1 shows the average macroeconomic response in these countries after they were hit by a hurricane. In the aftermath, these countries do some of the things we would expect households to do: accept nonmarket gifts (transfers from foreign countries) and borrow (by running a current account deficit). If we subtract nonmarket transfers and examine market behavior alone, the patterns are striking. As a fraction of GDP, investment is typically 3% to 6% higher than normal in the three years after a hurricane, and saving is 1% to 5% lower (excluding transfers). Combining the two effects, the current account (saving minus investment) falls dramatically and is 6% to 10% more in deficit than normal.

Hurricanes are extreme examples of economic shocks. They are not representative of the normal fluctuations that countries experience, but the size and randomness of the hurricanes allow us to look at the nations’ macroeconomic responses to such a shock. These responses illustrate some of the financial mechanisms that help open economies cope with all types of shocks, large and small, natural or human in origin.

In this chapter, we see how financially open economies can, in theory, reap gains from financial globalization. We first look at the factors that limit international borrowing and lending. Then, in the remaining sections of the chapter, we see how a nation’s ability to use international financial markets allows it to accomplish three different goals:

201

- consumption smoothing (steadying consumption when income fluctuates);

- efficient investment (borrowing to build a productive capital stock); and

- diversification of risk (by trading of stocks between countries).

Along the way, we look at how well the theoretical gains from financial globalization translate into reality (an area of some dispute among economists) and find that many of these gains have yet to be realized. In advanced countries, the gains from financial globalization are often large and more attainable, but in poorer countries the gains may be smaller and harder to realize. We want to understand why these differences exist, and what risks may arise for poor countries that attempt to capture the gains from financial globalization.