Chapter Introduction

305

Fixed Versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

This chapter provides a detailed analysis of the pros and cons of fixed and flexible exchange rate regimes. It stresses the classical criteria of integration and symmetry in the choice of regime. It also highlights two other virtues of fixed rates: (1) their use as a nominal anchor, and (2) they may also avoid large changes in external wealth in countries with dollarized liabilities. It investigates the theory and practice of fixed rate systems, and concludes with a brief history of the international monetary system.

- Exchange Rate Regime Choice: Key Issues

- Other Benefits of Fixing

- Fixed Exchange Rate Systems

- International Monetary Experience

- Conclusions

In truth, the gold standard is already a barbarous relic. All of us, from the Governor of the Bank of England downwards, are now primarily interested in preserving the stability of business, prices, and employment, and are not likely, when the choice is forced on us, deliberately to sacrifice these to the outworn dogma.…Advocates of the ancient standard do not observe how remote it now is from the spirit and the requirements of the age.

John Maynard Keynes, 1923

How many more fiascoes will it take before responsible people are finally convinced that a system of pegged exchange rates is not a satisfactory financial arrangement for a group of large countries with independent political systems and independent national policies?

Milton Friedman, 1992

The gold standard in particular—and even pegged exchange rates in general—have a bad name. But the gold standard’s having lost her name in the 1920s and 1930s should not lead one to forget her 19th century virtues.…Can these lost long-term virtues be retrieved without the world again being in thrall to the barbarous relic?…In an integrated world economy, the choice of an exchange rate regime—and thus the common price level—should not be left to an individual country. The spillover effects are so high that it should be a matter of collective choice.

Ronald McKinnon, 2002

Most students will have heard of the gold standard, but won't know much about it. Provide a brief introduction, and use it as a segue way to a brief survey of the historical evolution of regimes.

1. A brief history of exchange rate regimes:

a. 1870-1913, the classical gold standard

b. 1913-WWII, abandonment of gold, followed a brief return in the 1920s, then abandonment

c. Post WWII, the dollar standard of Bretton Woods

d. Early 1970s, collapse of Bretton Woods

e. Since then, flexible rates are most common

2. Why do some countries float, while others fix? Why do they change? This chapter investigates the advantages and disadvantages of different exchange rate regimes.

A century ago, economists and policy makers may have had their differences of opinion, but—unlike today—almost all of them agreed that a fixed exchange rate was the ideal choice of exchange rate regime. Even if some countries occasionally adopted a floating rate, it was usually with the expectation that they would soon return to a fixed or pegged rate.

The preferred method for fixing the exchange rate was the gold standard, a system in which the value of a country’s currency was fixed relative to an ounce of gold. As a result, the currency’s value was also fixed against all other currencies that were also pegged to gold. The requirements of maintaining the gold standard were strict: although monetary authorities could issue paper money, they had to be willing and able to exchange paper currency for gold at the official fixed rate when asked to do so.

306

Note that this wasn't really such a long time.

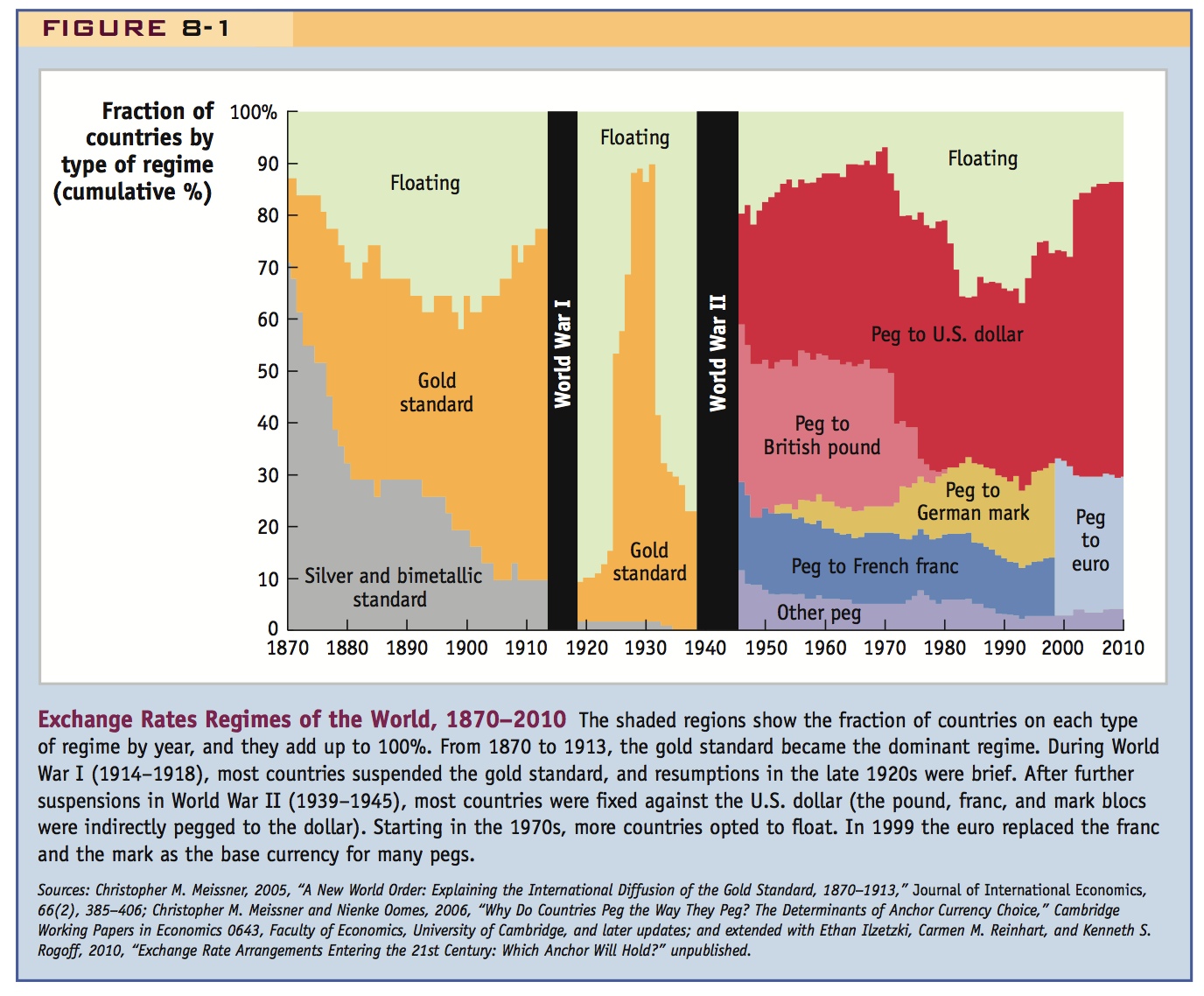

Figure 8-1 documents 140 years of exchange rate arrangements around the world. From 1870 to 1913, most of the world used the gold standard. At the peak in 1913, approximately 70% of the world’s countries were part of the gold standard system; a few floated (about 20%) or used other metallic standards (about 10%). Since 1913 much has changed. Adherence to the gold standard weakened during World War I, waxed and waned in the 1920s and 1930s, then was never seen again. In the 1940s, John Maynard Keynes and policy makers from all over the world designed a new system of fixed exchange rates, the Bretton Woods system.

In the period after World War II, the figure shows that many currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar in this system. Other currencies were pegged to the British pound, the French franc, and the German mark. Because the pound, franc, and mark were all pegged to the dollar at this time, the vast majority of the world’s currencies were directly or indirectly fixed on what amounted to a “dollar standard” system.

Like the gold standard, the dollar-based system didn’t endure either. Beginning in the early 1970s, floating exchange rates became more common (more than 30% of all currency regimes in the 1980s and 1990s); in recent years, fixed exchange rates have risen again in prominence. Remember that these data count all countries’ currencies equally, without any weighting for economic size (measured by GDP). In the larger economies of the world, and especially among the major currencies, floating regimes are more prevalent.

307

Why do some countries choose to fix and others to float? Why do they change their minds at different times? These are among the most enduring and controversial questions in international macroeconomics and they have been the cause of conflicts among economists, policy makers, and commentators for many years. On one side of the debate are those like Milton Friedman (quoted at the start of this chapter) who in the 1950s, against the prevailing gold standard orthodoxy, argued that floating rates are obviously to be preferred because of their clear economic and political advantages. On the opposing side of the debate are figures such as Ronald McKinnon (also quoted above) who think that only a system of fixed rates can encourage cooperative policy making, keep prices and output stable, and encourage international flows of trade and finance. In this chapter, we examine the pros and cons of different exchange rate regimes.