2 Other Benefits of Fixing

Two other benefits of fixing:

1.Fiscal Discipline, Seigniorage, and Inflation

There is often an incentive for governments to monetize their debts, generating seigniorage revenue from inflation. The conventional wisdom has long been that fixed rates are desirable as a way of credibly committing not to inflate. However, fixed rates are neither necessary nor sufficient for price stability: In theory any nominal anchor could achieve this end; furthermore, pegs can be changed, and badly managed could produce a currency crisis, after which inflation might erupt. Do fix rates improve price stability empirically? The evidence suggests that what matters for price stability is the use of a nominal anchor, not necessarily fixed rates. However, fixed rates do produce lower inflation rates than other regimes.

We began the chapter by emphasizing two key factors that influence the choice of fixed versus floating rate regimes: economic integration (market linkages) and economic similarity (symmetry of shocks). Other factors can play a role, however, and in this section, we explore some benefits of a fixed exchange rate regime that can be particularly important in emerging markets and developing countries.

Fiscal Discipline, Seigniorage, and Inflation

Give examples.

Explain the origin of the word.

One common argument in favor of fixed exchange rate regimes in developing countries is that an exchange rate peg prevents the government from printing money to finance government expenditure. Under such a financing scheme, the central bank is called upon to monetize the government’s deficit (i.e., give money to the government in exchange for debt). This process increases the money supply and leads to high inflation. The source of the government’s revenue is, in effect, an inflation tax (called seigniorage) levied on the members of the public who hold money (see Side Bar: The Inflation Tax).

321

Details about seigniorage

1. Liability Dollarization, National Wealth, and Contractionary Depreciations

External assets are never entirely denominated in domestic currency, so exchange rate fluctuations can change domestic wealth: A depreciation will lower domestic wealth if foreign currency liabilities exceed foreign currency assets. If the country has no external assets denominated in dollars, but does have external liabilities in dollars, then a depreciation will reduce its wealth.

a. Destabilizing Wealth Shocks

This means that depreciation may result in adverse wealth effects: If wealth falls, households might reduce consumption, and firms might find it harder to borrow to invest. This is particularly likely to happen in developing economies because they are debtors and much of their liabilities are dollarized.

b. Evidence Based on Changes in Wealth

Empirical evidence shows that depreciations reduce wealth in emerging economies.

c. Evidence Based on Output Contractions

Large depreciations after currency crises cause wealth losses that are strongly correlated with reductions in output.

d. Original Sin

Historically, most developing countries suffer from “original sin,” the inability to borrow in their own currencies. This is because foreign investors are afraid these countries will be unable to maintain prudent macro policies. But perhaps the sinners can find redemption: Maybe international institutions can help create markets for assets denominated in these currencies; maybe the countries can institute institutional reforms to reassure foreign investors. The lesson: In countries that cannot borrow in their own currencies, flexible exchange rates are less effective as a stabilization tool.

2. Summary

In Section 1, we saw that the two crucial factors in the choice of exchange rate regime are integration and symmetry. Now we have investigated two other benefits of a fixed rate: First, it may provide a good nominal anchor to stop inflation, particularly in cases where the central bank is not independent and has little credibility in fighting inflation. Second, a fixed rate might avoid large fluctuations in wealth caused by the valuation effects of changes in the exchange rate.

Strictly speaking, this should be M0 (base money) in an economy with a money multiplier > 1.

Ask the students what inflation rate would maximize seigniorage. Develop the intuition for the answer by having them think about the price a monopolist would set to maximize its revenues--where the price elasticity is 1. Give them a linear money demand, and have them solve for the seigniorage maximizing inflation rate.

The Inflation Tax

How does the inflation tax work? Consider a situation in which a country with a floating exchange rate faces a constant budget deficit and is unable to finance this deficit through domestic or foreign borrowing. To cover the deficit, the treasury department calls on the central bank to “monetize” the deficit by purchasing an amount of government bonds equal to the deficit.

For simplicity, suppose output is fixed at Y, prices are completely flexible, and inflation and the nominal interest rate are constant. At any instant, money grows at a rate ΔM/M = ΔP/P = π, so the price level rises at a rate of inflation π equal to the rate of money growth. The Fisher effect tells us that the nominal interest rate is i = r* + π, where r* is the real world interest rate.

This ongoing inflation erodes the real value of money held by households. If a household holds M/P in real money balances, then a moment later when prices have increased by an amount ΔM/M = ΔP/P = π, a fraction π of the real value of the original M/P is lost to inflation. The cost of the inflation tax to the household is π × M/P. For example, if I hold $100, the price level is currently 1, and inflation is 1%, then after one period the initial $100 is worth only $99 in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, and prices are 1.01.

What is the inflation tax worth to the government? It can spend the extra money printed ΔM to buy real goods and services worth ΔM/P = (ΔM/M) × (M/P) = π × (M/P). For the preceding example, the expansion of the money supply from $100 to $101, provides financing worth $1 to the government. The real gain for the government equals the real loss to the households.

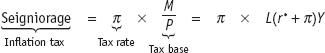

The amount that the inflation tax transfers from household to the government is called seigniorage, which can be written as

The two terms are often viewed as the tax rate (here, the inflation rate π) and the tax base (the thing being taxed; here, real money balances M/P = L). The first term rises as inflation π rises, but the second term goes to zero as π gets large because if inflation becomes very high, people try to hold almost no money, that is, real money demand given by L(i) = L(r* + π)Y falls to zero.

Because of these two offsetting effects, the inflation tax tends to hit diminishing returns as a source of real revenue: as inflation increases, the tax generates increasing real revenues at first, but eventually the rise in the first term is overwhelmed by the fall in the second term. Once a country is in a hyperinflation, the economy is usually well beyond the point at which real inflation tax revenues are maximized.

Review this important fact.

High inflation and hyperinflation (inflation in excess of 50% per month) are undesirable. If nothing else (such as fiscal discipline) can prevent them, a fixed exchange rate may start to look more attractive. Does a fixed exchange rate rule out inflationary finance and the abuse of seigniorage by the government? In principle, yes, but this anti-inflationary effect is not unique to a fixed exchange rate. As we saw in an earlier chapter on the monetary approach to exchange rates, any nominal anchor (such as money, exchange rate, or inflation targets) will have the same effect.

Maybe even currency boards?

If a country’s currency floats, its central bank can print a lot or a little money, with very different inflation outcomes. If a country’s currency is pegged, the central bank might run the peg well, with fairly stable prices, or it might run the peg so badly that a crisis occurs, the exchange rate collapses, and inflation erupts.

Nominal anchors imply a “promise” by the government to ensure certain monetary policy outcomes in the long run. However, these promises do not guarantee that the country will achieve these outcomes. All policy announcements including a fixed exchange rate are to some extent “cheap talk.” If pressure from the treasury to monetize deficits gets too strong, the commitment to any kind of anchor could fail.

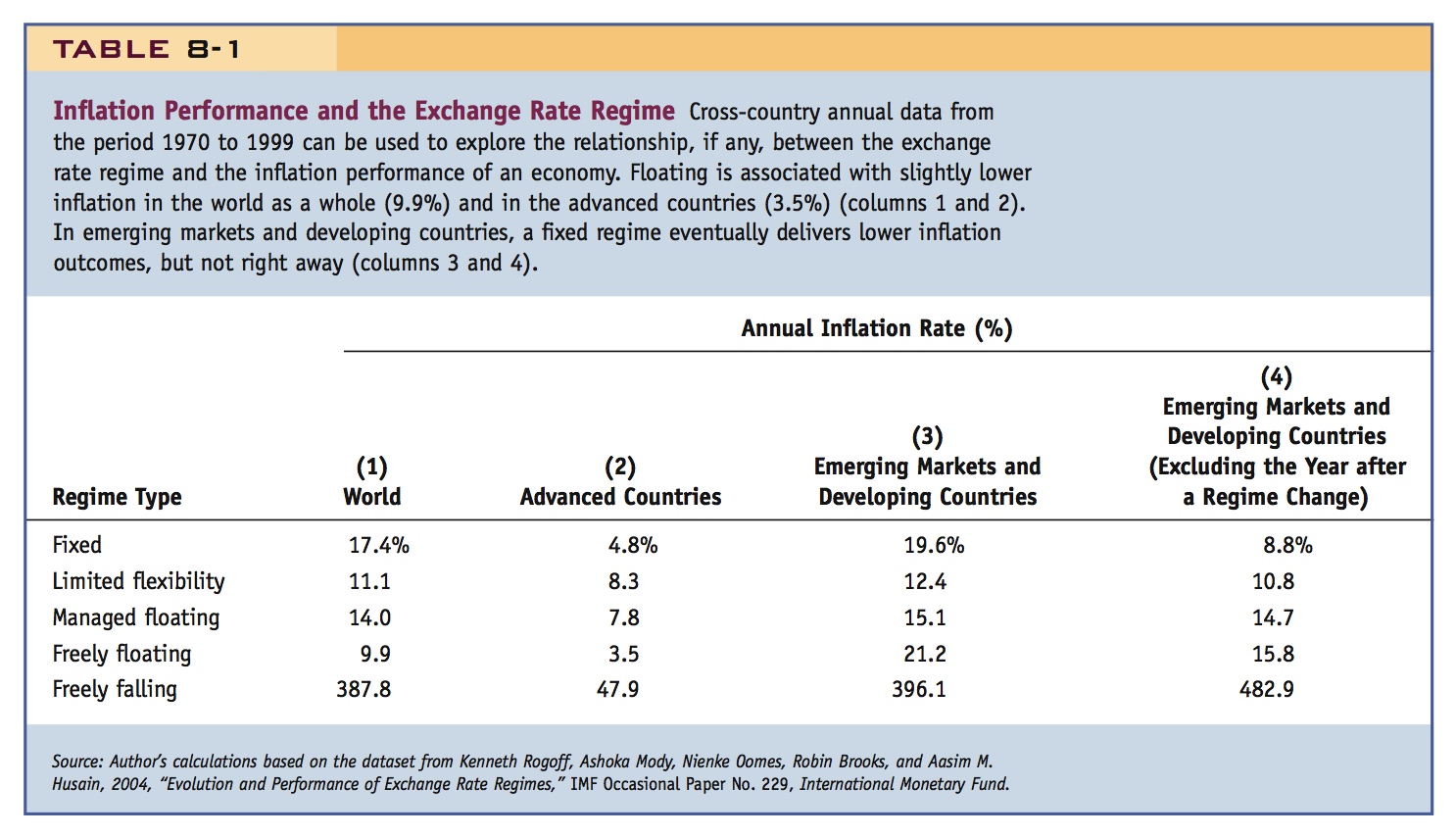

The debate over whether fixed exchange rates improve inflation performance cannot be settled by theory alone—it is an empirical question. What has happened in reality? Table 8-1 lays out the evidence on the world inflation performance from 1970 to 1999. Average inflation rates are computed for all countries and for subgroups of countries: advanced economies (rich countries), emerging markets (middle-income countries integrated in world capital markets), and developing countries (other countries).

322

These are striking, even surprising. Emphasize the need for a nominal anchor again, any anchor evidently.

For all countries (column 1), we can see that average inflation performance appears largely unrelated to the exchange rate regime, whether the choice is a peg (17.4%), limited flexibility (11.1%), managed floating (14.0%), or freely floating (9.9%). Only the “freely falling” has astronomical rates of inflation (387.8%). Similar results hold for the advanced countries (column 2) and for the emerging markets and developing countries (column 3). Although average inflation rates are higher in the latter sample, the first four regimes have fairly similar inflation rates, with fixed and freely floating almost the same.

We may conclude that as long as monetary policy is guided by some kind of nominal anchor, the particular choice of fixed and floating may not matter that much.13 Possibly the only place where the old conventional wisdom remains intact is in the developing countries, where fixed exchange rates can help to deliver lower inflation rates after high inflations or hyperinflations. Why? In those situations, people may need to see the government tie its own hands in a very open and verifiable way for expectations of perpetually high inflation to be lowered, and a peg is one way to do that. This can be seen in Table 8-1, column 4. If we exclude the first year after a change in the exchange rate regime, we exclude the periods after high inflations and hyperinflations when inflation (and inflationary expectations) may still persist even after the monetary and exchange rate policies have changed. Once things settle down in years two and later, fixed exchange rates generally do deliver lower (single-digit) inflation rates than other regimes.

323

- The lesson: Fixed exchange rates are neither necessary nor sufficient to ensure good inflation performance in many countries. In developing countries beset by high inflation, an exchange rate peg may be the only credible anchor.

Liability Dollarization, National Wealth, and Contractionary Depreciations

As we learned in the balance of payments chapter, exchange rate changes can have a big effect on a nation’s wealth. External assets and liabilities are never entirely denominated in local currency, so movements in the exchange rate can affect their value. For developing countries and emerging markets afflicted by the problem of liability dollarization, the wealth effects can be large and destabilizing, providing another argument for fixing the exchange rate.

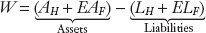

Suppose there are just two countries and two currencies, Home and Foreign. Home has external assets AH denominated in Home currency (say, pesos) and AF denominated in Foreign currency (say, U.S. dollars). Similarly, it has external liabilities LH denominated in Home currency and LF denominated in Foreign currency. The nominal exchange rate is E (with the units being Home currency per unit of Foreign currency—here, pesos per dollar).

The value of Home’s dollar external assets and liabilities can be expressed in pesos as EAF and ELF, respectively, using an exchange rate conversion. Hence, the Home country’s total external wealth is the sum total of assets minus liabilities expressed in local currency:

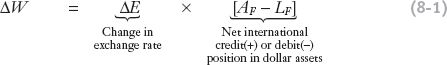

Now suppose there is a small change ΔE in the exchange rate, all else equal. This does not affect the values of AH and LH, but it does change the values of EAF and ELF expressed in pesos. We can express the resulting change in national wealth as

The expression is intuitive and revealing. After a depreciation (ΔE > 0), the wealth effect is positive if Foreign currency assets exceed Foreign currency liabilities (the net dollar position in brackets is positive) and negative if Foreign currency liabilities exceed Foreign currency assets (the net dollar position in brackets is negative).

Students will find the conclusion to this argument intuitive, but will get lost in the details. Numerical examples like this will help.

For example, consider first the case in which Home experiences a 10% depreciation, with assets of $100 billion and liabilities of $100 billion. What happens to Home wealth if it has $50 billion of assets in dollars and no liabilities in dollars? It has a net credit position in dollars, so it ought to gain. Half of assets and all liabilities are expressed in pesos, so their value does not change. But the value of the half of assets denominated in dollars will rise in peso terms by 10% times $50 billion. In this case, a 10% depreciation increases national wealth by 5% or $5 billion because it increases the value of a net foreign currency credit position.

Now look at the case in which Home experiences a 10% depreciation, as in the preceding example, with zero assets in dollars and $50 billion of liabilities in dollars. All assets and half of liabilities are expressed in pesos, so their value does not change. But the value of the half of liabilities denominated in dollars will rise in peso terms by 10% times $50 billion. In this case, a depreciation decreases national wealth by 5% or $5 billion because it increases the value of a net foreign currency debit position.

324

This is a good way to tie things back to the model.

Destabilizing Wealth Shocks Why do these wealth effects have implications for stabilization policy? In the previous chapter, we saw that nominal exchange rate depreciation can be used as a short-run stabilization tool in the IS-LM-FX model. In the face of an adverse demand shock in the Home country, for example, a depreciation will increase Home aggregate demand by switching expenditure toward Home goods. Now we can see that exchange rate movements can influence aggregate demand by affecting wealth.

These effects matter because, in more complex short-run models of the economy, wealth affects the demand for goods. For example,

Recommend including wealth, and other things like expectations and interest rates.

- Consumers might spend more when they have more wealth. In this case, the consumption function would become C(Y − T, Total wealth), and consumption would depend not just on after-tax income but also on wealth.

- Firms might find it easier to borrow if their wealth increases (e.g., wealth increases the net worth of firms, increasing the collateral available for loans). The investment function would then become I(i, Total wealth), and investment would depend on both the interest rate and wealth.

We can now begin to understand the importance of the exchange rate valuation effects summarized in Equation (8-1). This equation says that countries have to satisfy a special condition to avoid changes in external wealth whenever the exchange rate moves: the value of their foreign currency external assets must exactly equal foreign currency liabilities. If foreign currency external assets do not equal foreign currency external liabilities, the country is said to have a currency mismatch on its external balance sheet, and exchange rate changes will affect national wealth.

If foreign currency assets exceed foreign currency liabilities, then the country experiences an increase in wealth when the exchange rate depreciates. From the point of view of stabilization, this is likely to be beneficial: additional wealth will complement the direct stimulus to aggregate demand caused by a depreciation, making the effect of the depreciation even more expansionary. This scenario applies to only a few countries, most notably the United States.

However, if foreign currency liabilities exceed foreign currency assets, a country will experience a decrease in wealth when the exchange rate depreciates. From the point of view of stabilization policy, this wealth effect is unhelpful because the fall in wealth will tend to offset the conventional stimulus to aggregate demand caused by a depreciation. In principle, if the valuation effects are large enough, the overall effect of a depreciation can be contractionary! For example, while an interest rate cut might boost investment, and the ensuing depreciation might also boost the trade balance, such upward pressure on aggregate demand may well be offset partially or fully (or even outweighed) by decreases in wealth that put downward pressure on demand.

We now see that if a country has an adverse (i.e., negative) net position in foreign currency assets, then the conventional arguments for stabilization policy (and the need for floating) are weak. For many emerging market and developing economies, this is a serious problem. Most of these poorer countries are net debtors, so their external wealth shows a net debit position overall. But their net position in foreign currency is often just as much in debit, or even more so, because their liabilities are often close to 100% dollarized.

325

Summarize all this: Exchange rate fluctuations cause developing countries with significant amounts of debt denominated in foreign currency to suffer large changes in wealth, which have significant real effects.

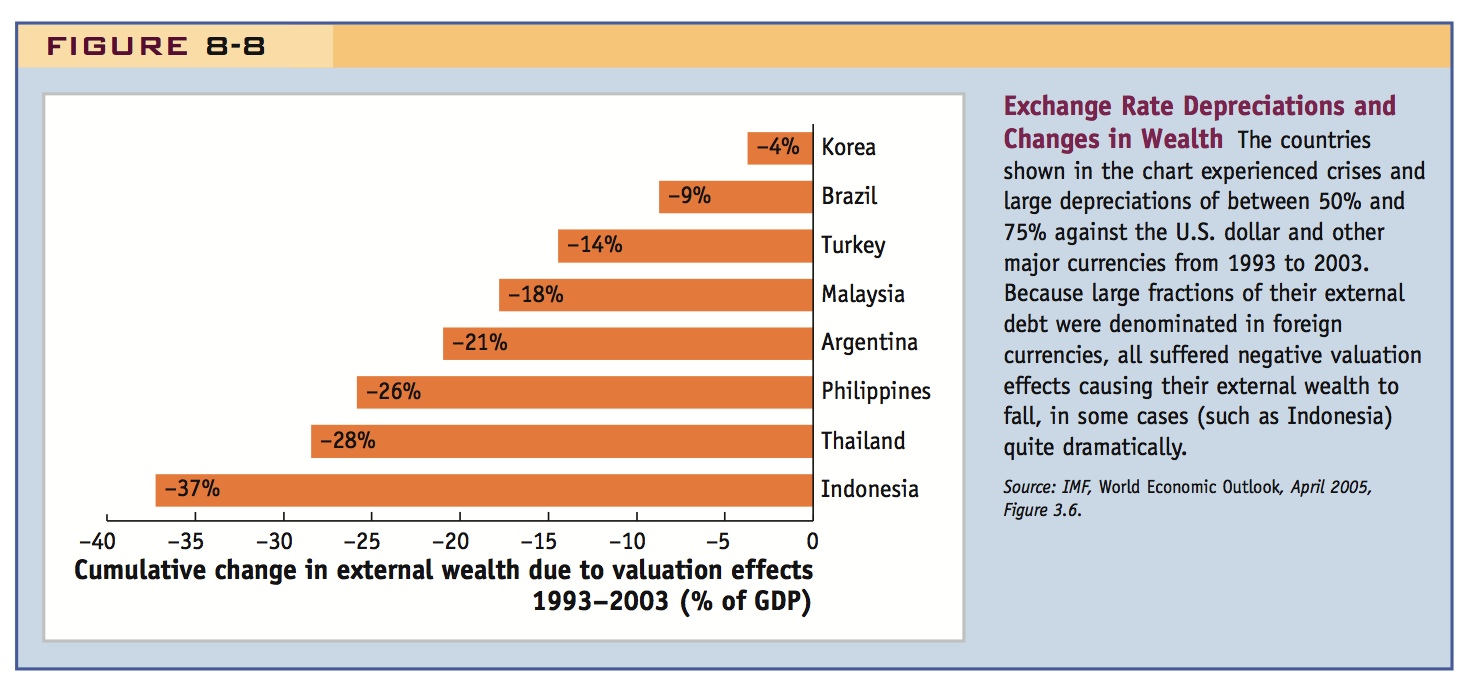

Evidence Based on Changes in Wealth When emerging markets experience large depreciations, they often suffer serious collapses in external wealth. To illustrate the severity of this problem, Figure 8-8 shows the impact of exchange rate valuation effects on wealth in eight countries. All the countries experienced exchange rate crises during the period in which the domestic currency lost much of its value relative to the U.S. dollar. Following the 1997 Asian crisis, Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand saw their currencies depreciate by about 50%; Indonesia’s currency depreciated by 75%. In 1999 the Brazilian real depreciated by almost 50%. In 2001 Turkey’s lira depreciated suddenly by about 50%, after a long slide. And in Argentina, the peso depreciated by about 75% in 2002.

All of these countries also had large exposure to foreign currency debt with large levels of currency mismatch. The Asian countries had borrowed extensively in yen and U.S. dollars; Turkey, Brazil, and Argentina had borrowed extensively in U.S. dollars. As a result of the valuation effects of the depreciations and the liability dollarization all of these countries saw large declines in external wealth. Countries such as Brazil and Korea escaped lightly, with wealth falling cumulatively by only 5% to 10% of annual GDP. Countries with larger exposure to foreign currency debt, or with larger depreciations, suffered much more: in Argentina, the Philippines, and Thailand, the losses were 20% to 30% of GDP and in Indonesia almost 40% of GDP.

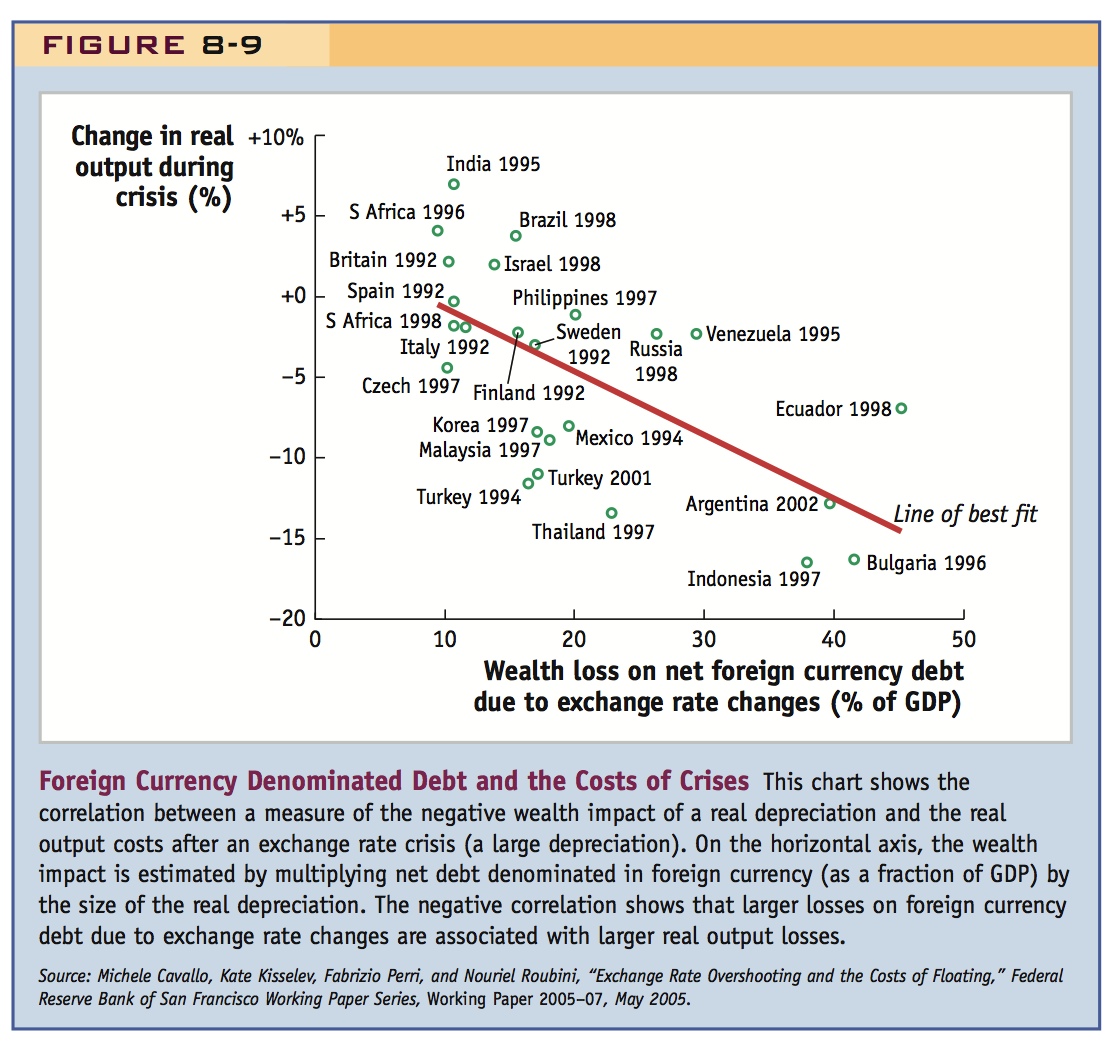

Evidence Based on Output Contractions Figure 8-8 tells us that countries with large liability dollarization suffered large wealth effects. But do these wealth effects cause so much economic damage that a country might reconsider its exchange rate regime?

Figure 8-9 suggests that wealth effects are associated with contractions and that the damage is fairly serious. Economists Michele Cavallo, Kate Kisselev, Fabrizio Perri, and Nouriel Roubini found a strong correlation between wealth losses on net foreign currency liabilities suffered during the large depreciations seen after an exchange rate crisis, and a measure of the subsequent fall in real output.14 For example, after 1992 Britain barely suffered any negative wealth effect and, as we noted earlier, did well in its subsequent economic performance: Britain in 1992 sits in the upper left part of this scatterplot (very small wealth loss, no negative impact on GDP). At the other extreme (in the lower right part of this scatterplot), are countries like Argentina and Indonesia, where liability dollarization led to massive wealth losses after the 1997 crisis (large wealth loss, large negative impact on GDP).

326

Original Sin Such findings have had a powerful influence among international macroeconomists and policymakers in recent years. Previously, external wealth effects were largely ignored and poorly understood. But now, after the adverse consequences of recent large depreciations, macroeconomists recognize that the problem of currency mismatch, driven by liability dollarization, is a key factor in the economic health of many developing countries and should be considered when choosing an exchange rate regime.

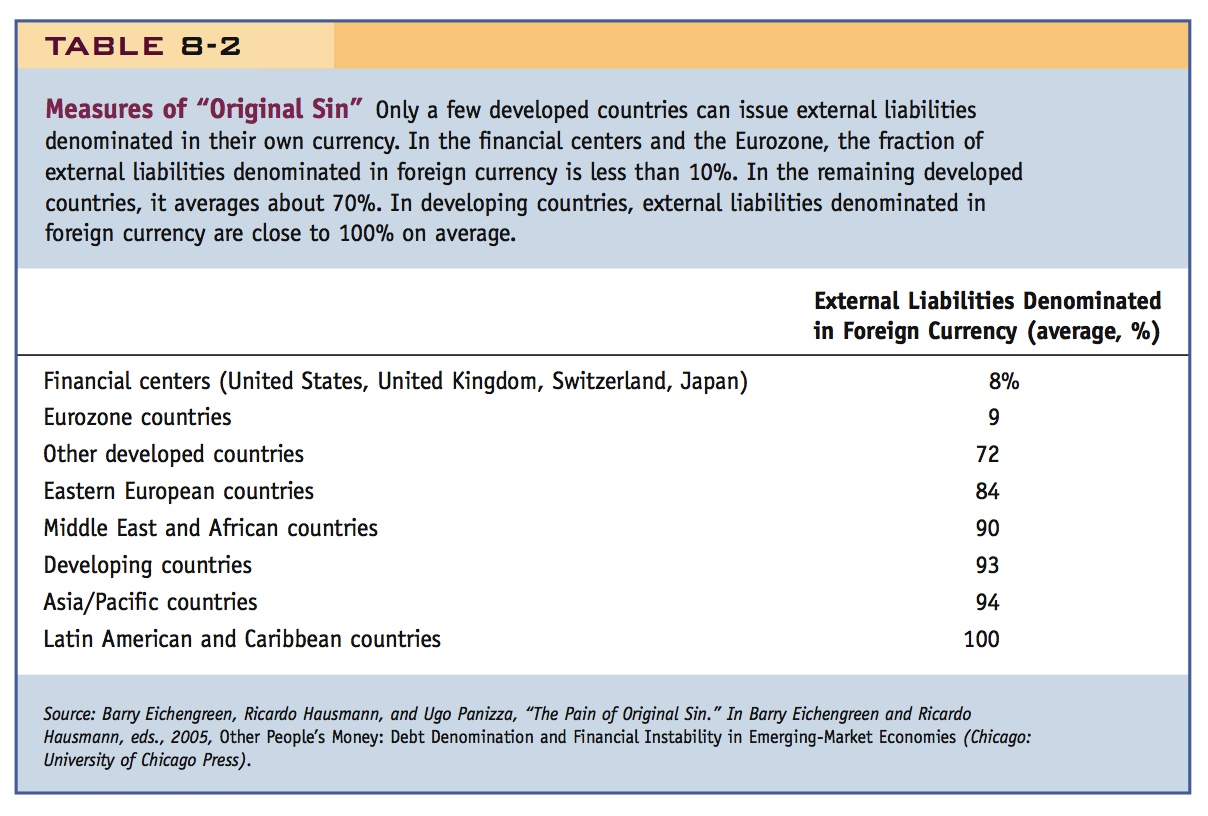

Yet these kinds of losses due to currency mismatch are an old problem. In the long history of international investment, one remarkably constant feature has been the inability of most countries—especially poor countries on the periphery of global capital markets—to borrow from abroad in their own currencies. In the late nineteenth century, such countries had to borrow in gold, or in a “hard currency” such as British pounds or U.S. dollars. The same is true today, as is apparent from Table 8-2. In the world’s financial centers and the Eurozone, only a small fraction of external liabilities are denominated in foreign currency. In other countries, the fraction is much higher; in developing countries, it is close to 100%.

327

Return to the theme of the importance of institutions.

Economists Barry Eichengreen, Ricardo Hausmann, and Ugo Panizza used the term “original sin” to refer to a country’s inability to borrow in its own currency.15 As the term suggests, an historical perspective reveals that the “sin” is highly persistent and originates deep in a country’s historical past. Countries with a weak record of macroeconomic management—often due to institutional or political weakness—have in the past been unable to follow prudent monetary and fiscal policies, so the real value of domestic currency debts was frequently eroded by periods of high inflation. Because creditors were mostly unwilling to hold such debt, domestic currency bond markets did not develop, and creditors would lend only in foreign currency which promised a more stable long-term value.

Stock Search International

Still, sinners can find redemption. One view argues that the problem is a global capital market failure: for many small countries, the pool of their domestic currency liabilities may be too small to offer any significant risk diversification benefits to foreign investors. In this case, multinational institutions could step in to create markets for securities in the currencies of small countries, or in baskets of such currencies. Another view argues that as such countries improve their institutional quality, design better policies, secure a low-inflation environment, and develop a better reputation, they will eventually free themselves from original sin and be able to issue domestic and even external debt in their own currencies. Many observers think this is already happening. Habitual “sinners” such as Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Uruguay have recently been able to issue some debt in their own currency. In addition, many emerging countries have been reducing currency mismatch: many governments have been piling up large stocks of foreign currency assets in central bank reserves and sovereign wealth funds and both governments and in some cases the private sectors have been reducing their reliance on foreign currency loans. The recent trends indicate substantial progress in reducing original sin as compared with the 1990s.16

328

Yet any optimism must be tempered with caution. Only time will tell whether countries have really turned the corner and put their “sinful” ways behind them. Progress on domestic-currency borrowing is still very slow in many countries, and this still leaves the problem of currency mismatches in the private sector. While private sector exposure could be insured by the government, that insurance could, in turn, introduce the risk of abuse in the form of moral hazard, the risk that insured entities (here, private borrowers) will engage in excessive risk taking, knowing that they will be bailed out if they incur losses. This moral hazard could then create massive political problems, because it may not be clear who, in a crisis, would receive a public-sector rescue, and who would not. Why can’t the private sector simply hedge all its exchange rate risk? This solution would be ideal, but in many emerging markets and developing countries, currency derivative markets are poorly developed, many currencies cannot be hedged at all, and the costs are high.

The punch line.

If developing countries cannot avoid currency mismatches, they must try to cope with them. One way to cope is to reduce or stop external borrowing, but countries are not eager to give up all borrowing in world capital markets. A more feasible alternative is for developing countries to minimize or eliminate valuation effects by limiting the movement of the exchange rate. This is indeed what many countries are doing, and evidence shows that the larger a country’s stock of foreign currency liabilities relative to GDP, the more likely that country is to peg its currency to the currency in which the external debt is issued.17

- The lesson: in countries that cannot borrow in their own currency, floating exchange rates are less useful as a stabilization tool and may be destabilizing. Because this outcome applies particularly to developing countries, they will prefer fixed exchange rates to floating exchange rates, all else equal.

329

Summary

We began the chapter by emphasizing the two key factors that influence the choice of fixed versus floating rate regimes: economic integration (market linkages) and economic similarity (symmetry of shocks). But we now see that many other factors can affect the benefits of fixing relative to floating.

This is a catchy phrase around which an entire literature has developed. However, the word "fear" has connotations of irrationality that are inappropriate: Point out that the argument is simply that some developing countries may have extra reasons to prefer fixed rates.

A fixed exchange rate may have some additional benefits in some situations. It may be the only transparent and credible way to attain and maintain a nominal anchor, a goal that may be particularly important in emerging markets and developing countries with weak institutions, a lack of central bank independence, strong temptations to use the inflation tax, and poor reputations for monetary stability. A fixed exchange rate may also be the only way to avoid large fluctuations in external wealth, which can be a problem in emerging markets and developing countries with high levels of liability dollarization. These may be powerful additional reasons to fix, and they seem to apply with extra force in developing countries. Therefore, such countries may be less willing to allow their exchange rates to float—a situation that some economists describe as a fear of floating.

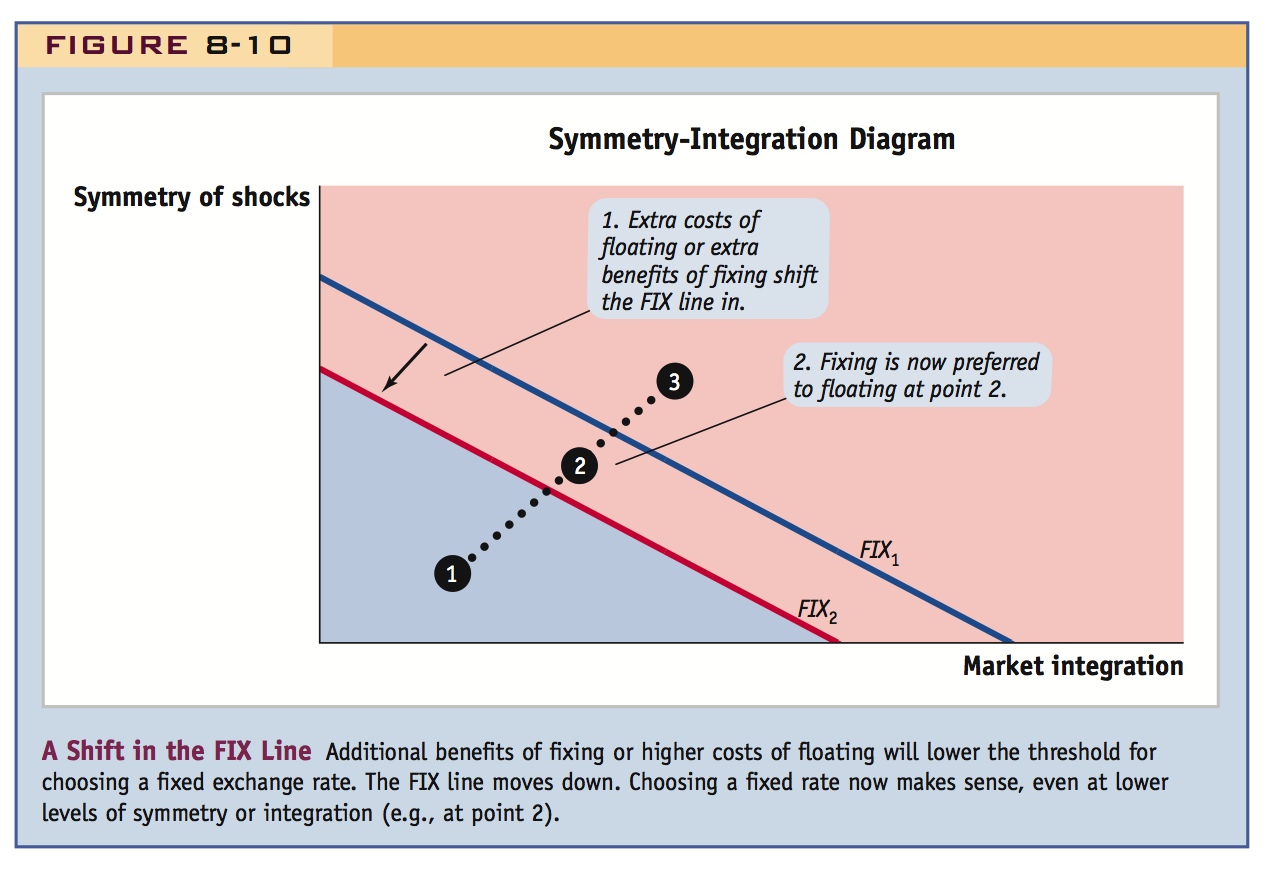

To illustrate the influence of additional costs and benefits, consider a Home country thinking of pegging to the U.S. dollar as a base currency (Figure 8-10). A Home country with a fear of floating would perceive additional benefits to a fixed exchange rate, and would be willing to peg its exchange at lower levels of integration and similarity. We would represent this choice as an inward shift of the FIX line from FIX1 to FIX2. Without fear of floating, based on FIX1, the Home country would float with symmetry-integration measures given by points 1 and 2, and fix at point 3. But if it had fear of floating, based on FIX2, it would elect to fix at point 2 because the extra benefits of a fixed rate lower the threshold.

330