Chapter Introduction

165

Increasing Returns to Scale and Monopolistic Competition

- Basics of Imperfect Competition

- Trade Under Monopolistic Competition

- The North American Free Trade Agreement

- Intra-Industry Trade and the Gravity Equation

- Conclusions

Foreign trade, then,…[is] highly beneficial to a country, as it increases the amount and variety of the objects on which revenue may be expended.

David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Chapter 7

The idea that a simple government policy [free trade between Canada and the United States] could raise productivity so dramatically is to me truly remarkable.

Professor Daniel Trefler, University of Toronto, 2005

1. Examples of intra-industry trade. Why does the U.S. export and import golf clubs?

2. The Ricardian model and HO can’t answer this. To answer it we must abandon perfect competition and its assumption of homogeneous goods. Instead, introduce product differentiation and imperfect competition.

3. Model has two key features:

a. Monopolistic competition: Product differentiation gives firms some market power, but they face competition from firms selling the same type of good.

b. Increasing returns to scale allows firms to reduce per unit cost by increasing production. This will create an incentive to trade internationally.

4. Show how the model helps explain actual trade patterns

a. Explains intra-industry trade

b. Predicts that large countries will trade more with each other—the gravity equation

5. Use the model to understand free-trade agreements (e.g. NAFTA)

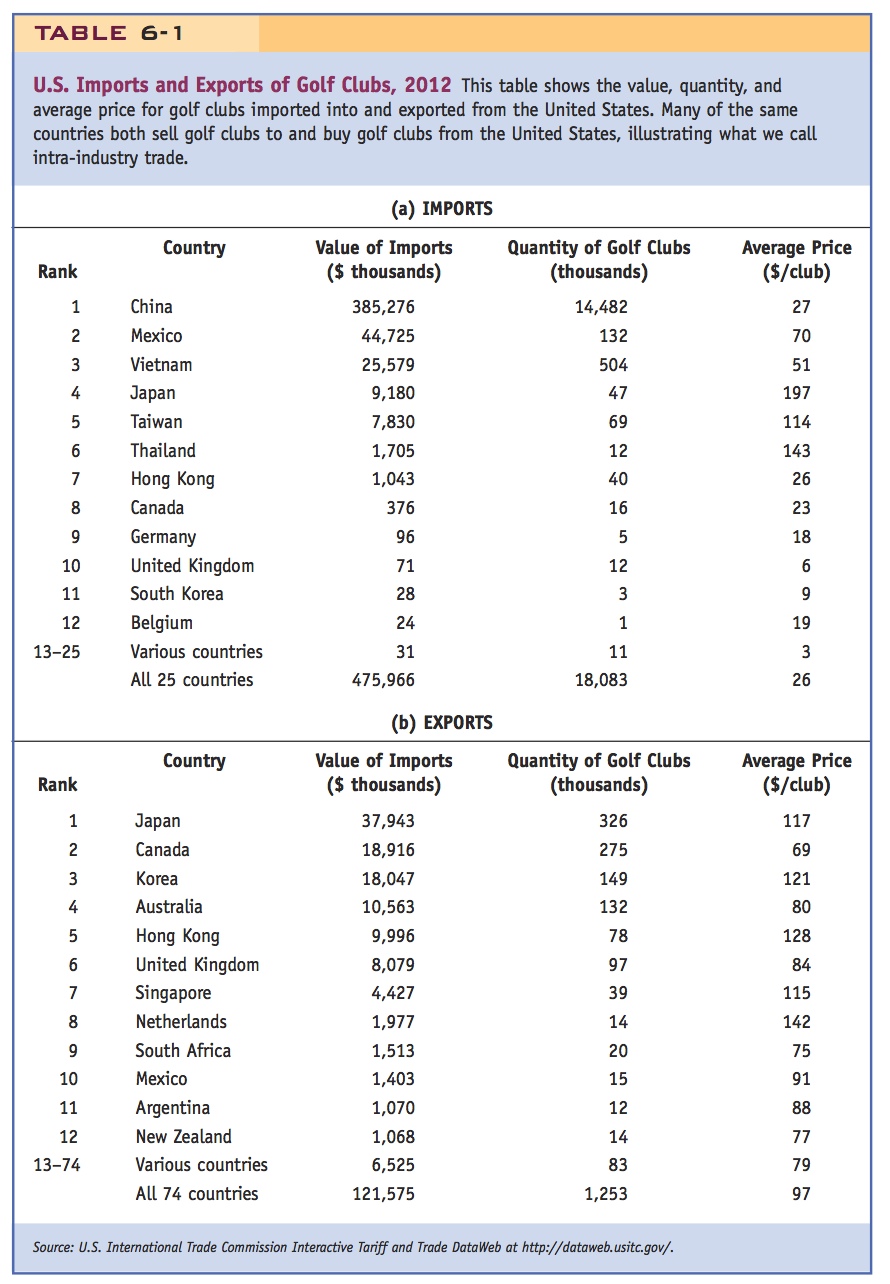

In Chapter 2, we looked at data for U.S. snowboard imports and considered the reasons why the United States imports this product from so many different countries. Now we look at another sporting good that the United States imports and exports in large quantities to illustrate how a country can both buy a product and sell it to other countries. In 2012 the United States imported golf clubs from 25 countries and exported them to 74 countries. In Table 6-1, we list the 12 countries that sell the most golf clubs to the United States and the 12 countries to which the United States sells the most golf clubs. The table also lists the amounts bought or sold and their average wholesale prices.

In panel (a), we see that China sells the most clubs to the United States, providing $385 million worth of golf clubs at an average price of $27 each. Next is Mexico, selling $45 million of clubs at an average wholesale price of $70 each.1 Vietnam comes next, exporting $26 million of clubs at an average price of $51, followed by Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand, each of which sells golf clubs to the United States with an average price exceeding $100. The higher average prices of golf clubs from these three countries as compared with Chinese and Vietnamese clubs most likely indicate that the clubs sold by Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand are of much higher quality. The clubs from the other top-selling countries have wholesale prices below $30. In total, the United States imported $476 million of golf clubs in 2012.

166

167

On the export side, shown in panel (b), the top destination for U.S. clubs is Japan, followed by Canada and South Korea. Notice that these three countries are also among the top 12 countries selling golf clubs to the United States. The average price for U.S. exports varies between $69 and $142 per club, higher than the price of all the imported clubs, except those from Mexico, Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand, which suggests that the United States is exporting high-quality clubs.

Many of the countries that sell to the United States also buy from the United States: 6 of the top 12 selling countries were also among the top 12 countries buying U.S. golf clubs in 2012. Of the 25 selling countries, 24 also bought U.S. golf clubs (the only country that sold clubs to the United States but did not also buy them was Bangladesh). Why does the United States export and import golf clubs to and from the same countries? The answer to this question is one of the “new” explanations for trade that we study in this chapter and the next. The Ricardian model (Chapter 2) and the Heckscher-Ohlin model (Chapter 4) explained why nations would either import or export a good, but those models do not predict the simultaneous import and export of a product, as we observe for golf clubs and many other goods.

Go ahead and introduce the term "intra-industry trade."

Call it the "new trade theory," to distinguish it from classical.

To explain why countries import and export the same product, we need to change some assumptions made in the Ricardian and Heckscher-Ohlin models. In those models, we assumed that markets were perfectly competitive, which means there are many small producers, each producing a homogeneous (identical) product, so none of them can influence the market price for the product. As we know just from walking down the aisles in a grocery or department store, most goods are differentiated goods; that is, they are not identical. Based on price differences in Table 6-1, we can see that the traded golf clubs are of different types and quality. So in this chapter, we drop the assumption that the goods are homogeneous, as in perfect competition, and instead assume that goods are differentiated and allow for imperfect competition, in which case firms can influence the price that they charge.

The new explanation for trade explored in this chapter involves a type of imperfect competition called monopolistic competition, which has two key features. The first feature, just mentioned, is that the goods produced by different firms are differentiated. By offering different products, firms are able to exert some control over the price they can charge for their particular product. Because the market in which the firms operate is not a perfectly competitive one, they do not have to accept the market price, and by increasing their price, they do not lose all their business to competitors. On the other hand, because these firms are not monopolists (i.e., they are not the only firm that produces this type of product), they cannot charge prices as high as a monopolist would. When firms produce differentiated products, they retain some ability to set the price for their product, but not as much as a monopolist would have.

Distinguish between internal and external economies of scale. Explain that the latter is still consistent with competitive equilibrium, but that the former is not.

Emphasize this by making a list of reasons for trade: (1) Differences in technology (Ricardo), (2) differences in endowments (HO), and now (3) economies of scale.

The second feature of monopolistic competition is increasing returns to scale, by which we mean that the average costs for a firm fall as more output is produced. For this reason, firms tend to specialize in the product lines that are most successful—by selling more of those products, the average cost for the production of the successful products falls. Firms can lower their average costs by selling more in their home markets but can possibly attain even lower costs from selling more in foreign markets through exporting. So increasing returns to scale create a reason for trade to occur even when the trading countries are similar in their technologies and factor endowments. Increasing returns to scale set the monopolistic competition trade model apart from the logic of the Ricardian and Heckscher-Ohlin models.

168

In this chapter, we describe a model of trade under monopolistic competition that incorporates product differentiation and increasing returns to scale. After describing the monopolistic competition model, the next goal of the chapter is to discuss how this model helps explain trade patterns that we observe today. In our golf club example, countries specialize in different varieties of the same type of product and trade them; this type of trade is called intra-industry trade because it deals with imports and exports in the same industry. The monopolistic competition model explains this trade pattern and also predicts that larger countries will trade more with one another. Just as the force of gravity is strongest between two large objects, the monopolistic competition model implies that large countries (as measured by their GDP) should trade the most.2 There is a good deal of empirical evidence to support this prediction, which is called the gravity equation.

The monopolistic competition model also helps us to understand the effects of free-trade agreements, in which free trade occurs among a group of countries. In this chapter, we use the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to illustrate the predictions of the monopolistic competition model. The policy implications of free-trade agreements are discussed in a later chapter.