3 The North American Free Trade Agreement

1.Objective: Use the model to explain the gains and costs of NAFTA

The idea that free trade will expand the range of products available to consumers is not new—it is even mentioned by David Ricardo in the quote at the beginning of this chapter. But the ability to carefully model the effects of trade under monopolistic competition is new and was developed in research during the 1980s by Professors Elhanan Helpman, Paul Krugman, and the late Kelvin Lancaster. That research was not just theoretical but was used to shed light on free-trade agreements, which guarantee free trade among a group of countries. In 1989, for example, Canada and the United States entered into a free-trade agreement, and in 1994 they were joined by Mexico in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The potential for Canadian firms to expand their output (and enjoy lower average costs) by selling in the United States and Mexico was a key factor in Canada’s decision to enter into these free-trade agreements. The quote from the Canadian economist Daniel Trefler at the beginning of the chapter shows that there was indeed a rise in productivity in Canada because of the free-trade agreements. We use NAFTA to illustrate the gains and costs predicted by the monopolistic competition model.

Gains and Adjustment Costs for Canada Under NAFTA

2.Gains and Adjustment Costs for Canada Under NAFTA

Daniel Trefler’s estimates: Substantial short-run adjustment costs, but new jobs ultimately were created in other sectors. In the long run productivity increased in industries most affected by NAFTA. Consumer prices fell and real wages increased.

Studies in Canada dating back to the 1960s predicted substantial gains from free trade with the United States because Canadian firms would expand their scale of operations to serve the larger market and lower their costs. A set of simulations based on the monopolistic competition model performed by the Canadian economist Richard Harris in the mid-1980s influenced Canadian policy makers to proceed with the free-trade agreement with the United States in 1989. Enough time has passed since then to look back and see how Canada has fared under the trade agreements with the United States and Mexico.

Key point: There are large short adjustment costs, but not in the long run. But some productivity gains.

Headlines: The Long and the Short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement describes what happened in Canada. Using data from 1988 to 1996, Professor Daniel Trefler of the University of Toronto found short-run adjustment costs of 100,000 lost jobs, or 5% of manufacturing employment. Some industries that faced particularly large tariff cuts saw their employment fall by as much as 15%. These are very large declines in employment. Over time, however, these job losses were more than made up for by the creation of new jobs elsewhere in manufacturing, so there were no long-run job losses as a result of the free-trade agreement.

What about long-run gains? Trefler found a large positive effect on the productivity of firms, with productivity rising as much as 18% over eight years in the industries most affected by tariff cuts, or a compound growth rate of 2.1% per year. For manufacturing overall, productivity rose by 6%, for a compound growth rate of 0.7% per year. The difference between these two numbers, which is 2.1 − 0.7 = 1.4% per year, is an estimate of how free trade with the United States affected the Canadian industries most affected by the tariff cuts over and above the impact on other industries. The productivity growth in Canada allowed for a modest rise in real earnings of 2.4% over the eight-year period for production workers, or 0.3% per year. We conclude that the prediction of the monopolistic competition model that surviving firms increase their productivity is confirmed for Canadian manufacturing. Those productivity gains led to a fall in prices for consumers and a rise in real earnings for workers, which demonstrates the first source of the gains from trade. The second source of gains from trade—increased product variety for Canadian consumers—was not measured in the study by Professor Trefler but has been estimated for the United States, as discussed later in this chapter.

179

Article on Trefler’s estimates.

3. Gains and Adjustment Costs for Mexico Under NAFTA

Very large tariff reductions in Mexico, from an average tariff of 14 percent on U.S. goods to 1 percent.

The Long and the Short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement

University of Toronto Professor Daniel Trefler studied the short-run effect of the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement on employment in Canada, and the long-run effect on productivity and wages.

There is good news and bad news in regard to the Canada/U.S. Free Trade Agreement. The good news is that the deal, especially controversial in Canada, has raised productivity in Canadian industry since it was implemented on January 1, 1989, benefiting both consumers and stakeholders in efficient plants. The bad news is that there were also substantial short-run adjustment costs for workers who lost their jobs and for stakeholders in plants that were closed because of new import competition or the opportunity to produce more cheaply in the south. “One cannot understand current debates about freer trade without understanding this conflict” between the costs and gains that flow from trade liberalization, notes Daniel Trefler in “The Long and Short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement” (NBER Working Paper No. 8293). His paper looks at the impact of the FTA on a large number of performance indicators in the Canadian manufacturing sector from 1989 to 1996. In the one-third of industries that experienced the largest tariff cuts in that period, ranging between 5 and 33 percent and averaging 10 percent, employment shrunk by 15 percent, output fell 11 percent, and the number of plants declined 8 percent. These industries include the makers of garments, footwear, upholstered furniture, coffins and caskets, fur goods, and adhesives. For manufacturing as a whole, the comparable numbers are 5, 3, and 4 percent, respectively, Trefler finds. “These numbers capture the large adjustment costs associated with reallocating resources out of protected, inefficient, low-end manufacturing,” he notes.

Since 1996, manufacturing employment and output have largely rebounded in Canada. This suggests that some of the lost jobs and output were reallocated to high-end manufacturing. On the positive side, the tariff cuts boosted labor productivity (how much output is produced per hour of work) by a compounded annual rate of 2.1 percent for the most affected industries and by 0.6 percent for manufacturing as a whole, Trefler calculates…. Surprisingly, Trefler writes, the tariff cuts raised annual earnings slightly. Production workers’ wages rose by 0.8 percent per year in the most affected industries and by 0.3 percent per year for manufacturing as a whole. The tariff cuts did not effect earnings of higher-paid non-production workers or weekly hours of production workers.

Source: Excerpted from David R. Francis, “Canada Free Trade Agreement,” NBER Digest, September 1, 2001, http://www.nber.org/digest/sep01/w8293.html. This paper by Daniel Trefler was published in the American Economic Review, 2004, 94(4), pp. 870–895.

Gains and Adjustment Costs for Mexico Under NAFTA

Note how large these tariffs were.

In the mid-1980s Mexican President Miguel de la Madrid embarked on a program of economic liberalization that included land reform and greater openness to foreign investment. Tariffs with the United States were as high as 100% on some goods, and there were many restrictions on the operations of foreign firms. De la Madrid believed that the economic reforms were needed to boost growth and incomes in Mexico. Joining NAFTA with the United States and Canada in 1994 was a way to ensure the permanence of the reforms already under way. Under NAFTA, Mexican tariffs on U.S. goods declined from an average of 14% in 1990 to 1% in 2001.4 In addition, U.S. tariffs on Mexican imports fell as well, though from levels that were much lower to begin with in most industries.

180

Article reports growth in trade after NAFTA and gains from economies of scale, lower prices, greater selection, and better quality. But also complains about U.S. tardiness in opening its border to Mexican trucks.

NAFTA Turns 15, Bravo!

This editorial discussed the impact of NAFTA on the U.S. and Mexican economies. It appeared in a U.S.-based pro-business publication focusing on Latin-American businesses.

As Americans and Mexicans celebrated the start of a new year yesterday, they had reason to celebrate another milestone as well: The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) turned 15. Despite the slowdown in both the U.S. and Mexican economies, trade between the two nations was expected to set a new record last year. In the first half of 2008, U.S.-Mexico trade grew by 9.6 percent to $183.7 billion. That follows a record $347 billion in trade in 2007. Compare that to the $81.5 billion in total two-way trade in 1993, the last year before NAFTA was implemented.

NAFTA has without a doubt been the primary reason for that success. It dramatically opened up Mexico’s economy to U.S. goods and investments, helping boost revenues for many U.S. companies. At the same time, Mexican companies were able to get duty-free access to the world’s largest market, resulting in more sales and more jobs there. The trade growth has meant benefits for both consumers and companies on each side of the border.

While China clearly dominates many of the products we buy in U.S. stores these days, Mexico also plays an important role. Mexico ranks third behind Canada and China among the top exporters to the U.S. market. But Mexico beats China when it comes to buying U.S. goods. During the first ten months last year [2008], Mexico imported U.S. products worth $129.4 billion—or more than twice the $61.0 billion China (with a much larger economy) bought from us….

NAFTA has benefited consumers in the U.S. through greater choice of products, in terms of selection, quality, and price, including many that are less expensive than pre-NAFTA…. NAFTA has allowed U.S. manufacturing giants from General Motors to General Electric to use economies of scale for their production lines. Prior to NAFTA, GM’s assembly plants in Mexico assembled small volumes of many products, which resulted in high costs and somewhat inferior quality, says Mustafa Mohatarem, GM’s chief economist. Now its plants in Mexico specialize in few high-volume products, resulting in low cost and high quality, he points out. The result benefits both U.S. and Mexican consumers….

To be sure, NAFTA is not perfect. For one, it didn’t even touch on Mexico’s sensitive oil sector, which should have been part of a comprehensive free trade agreement. Neither did it offer any teeth when it came to violations. For example, the shameful U.S. disregard for the NAFTA regulations on allowing Mexican trucks to enter the United States. Only in September last year [2008], as part of a pilot program by the Bush Administration, did the first Mexican trucks enter the United States—after a delay of eight years…thanks to opposition from U.S. unions and lawmakers…. Many economists also are critical of NAFTA’s labor and environmental side agreements, which President Bill Clinton negotiated in order to support the treaty.

However, all in all NAFTA has been of major benefit for both the United States and Mexico. Any renegotiation of NAFTA, as president-elect Barack Obama pledged during last year’s campaign, would negatively harm both economies just as they now suffer from economic recession. It would also harm our relations with Mexico, our top trading partner in Latin America. Hopefully, pragmatism will win the day in Washington, D.C. this year, as our new president aims to find a way to get the U.S. economy back on track. Leaving NAFTA alone would be a good start.

In the meantime, we congratulate NAFTA on its 15 years. Feliz Cumpleaños.

Source: Editors, Latin Business Chronicle, January 2, 2009, electronic edition.

How did the fall in tariffs under NAFTA affect the Mexican economy? We will review the evidence on productivity and wages below, but first, you should read Headlines: NAFTA Turns 15, Bravo! This editorial was written in 2009, the fifteenth anniversary of the beginning of NAFTA, and appeared in a U.S.-based pro-business publication focusing on Latin-American businesses. It makes a number of arguments in favor of NAFTA that we have also discussed, including increasing returns to scale and product variety for consumers. But it also points out some defects of NAFTA, including the tardiness of the United States in allowing an open border for trucks from Mexico, and the environmental and labor side agreements (discussed in a later chapter). Even after 15 years, Mexican trucks were not permitted into the United States, and this fact led Mexico to retaliate by imposing tariffs on some U.S. goods. Two years later, in 2011, the United States finally agreed to allow Mexican trucks to cross the border to deliver goods.5 In Headlines: Nearly 20 Years After NAFTA, First Mexican Truck Arrives In U.S. Interior, we describe this milestone in the economic relations between the United States and Mexico.

181

The U.S. finally allows Mexican trucks across the border.

a. Productivity in Mexico

Rapid increase in productivity in maquiladora plants.

b. Real Wages and Incomes

Real wages fell from 1994 to 1997. Why? The peso crisis, which had nothing to do with NAFTA. Since then real wages have increased, especially for higher-income workers. The biggest winners from NAFTA were higher-income workers in the maquiladora sector.

c. Adjustment Costs in Mexico

Surprisingly little effect on the Mexican corn industry, perhaps due to phased-in tariff reductions and government subsidies. Employment in maquiladora sector increased until 2000, then fell. Why? U.S. recession, competition from China, overvalued peso. Not due to NAFTA per se, but from increased international competition.

4. Gains and Adjustment Costs for the United States Under NAFTA

It is hard to estimate the effects of NAFTA on U.S. productivity, so the focus has been on estimating the gains from increased product variety.

i. Expansion of Variety to the United States

Assume that an expansion in variety has an effect similar to a reduction in import prices. Then the value to U.S. consumers of increased variety of goods imported from Mexico in the first 9 years of NAFTA was about $5.5 billion a year; in 2003 $11 billion.

ii. Adjustment Costs in the United States

Measure the temporary effects on unemployment with TAA claims: NAFTA displaced about 440,000 workers per year, about 13 percent of total displacement in manufacturing. Alternatively, compare wages lost by displaced workers to consumer gains: Total lost wages = $ 5.4 billion (per year) in the first 9 years of NAFTA, but the gains to consumers reported above are much larger in that the employment costs are temporary, while the gains to consumers are permanent, and will grow over time.

5. Summary of NAFTA

The model predicts two gains from trade: (1) enhanced productivity, and hence lower prices; (2) increased product variety. Productivity increased in the export sectors of Canada and Mexico. In the U.S., product variety increased, and prices fell. For the U.S. and Canada, the long-run gains of NAFTA exceed the short-run costs. For Mexico, it is not so clear because of the peso crisis. But real wages are increasing, especially for high-income workers in the maquiladora sector.

Nearly 20 Years After NAFTA, First Mexican Truck Arrives In U.S. Interior

On October 21, 2011, the first big-rig truck from Mexico crossed the border into Laredo, Texas, under a trucking program that was agreed to in NAFTA but that took 17 years to implement.

Nearly two decades after the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the first Mexican truck ventured into the U.S. under provisions of the controversial treaty. With little fanfare, a white tractor-trailer with Mexican license plates entered the courtyard of the Atlas Copco facility in Garland, Texas on Saturday afternoon to unload a Mexico-manufactured metal structure for drilling oil wells.

The delivery marked the first time that a truck from Mexico reached the U.S. interior under the 17-year-old trade agreement, which was supposed to give trucks from the neighboring countries access to highways on both sides of the border. The Obama administration signed an agreement with Mexico to end the long dispute over the NAFTA provision in July that also removes $2 billion in duties on American goods. “We were prepared for this a long time ago because we met the requirements and complied with the rules of cross-border transportation, which made us earn the trust of American companies,” said Gerardo Aguilar, a manager for “Transportes Olympic,” the only Mexican company authorized to operate its trucks in the U.S. The long-delayed door-to-door delivery was launched with a bi-national ceremony Friday to mark the truck’s crossing at the international bridge “World Trade” in Laredo, Tex., the entry point for 40 percent of products imported from Mexico.

Source: The Huffington Post, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/10/24/nearly-20-years-after-nafta-first-mexican-arrives-in-us-interior_n_1028630.html, First Posted: 10/24/11 06:08 PM ET Updated: 12/24/11 05:12 AM ET

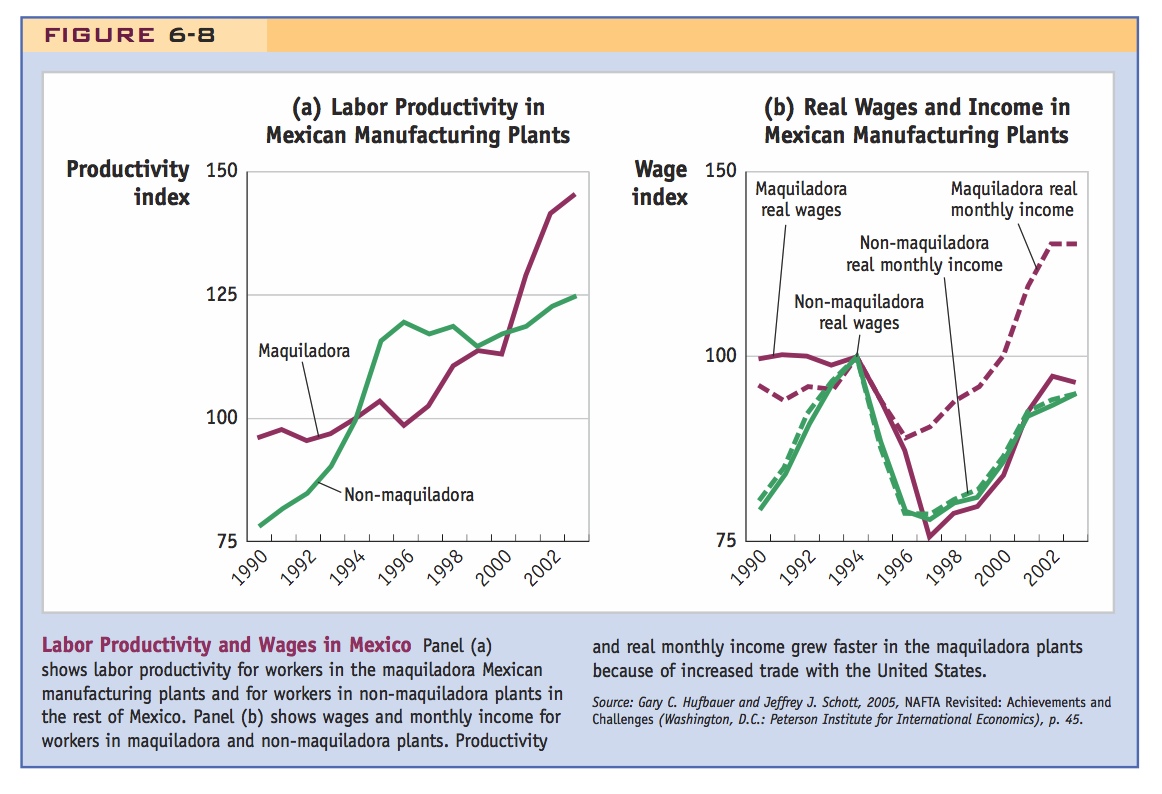

Productivity in Mexico As we did for Canada, let us investigate the impact of NAFTA on productivity in Mexico. In panel (a) of Figure 6-8, we show the growth in labor productivity for two types of manufacturing firms: the maquiladora plants, which are close to the border and produce almost exclusively for export to the United States, and all other nonmaquiladora manufacturing plants in Mexico.6 The maquiladora plants should be most affected by NAFTA. In panel (b), we also show what happened to real wages and real incomes.

182

Substantial

For the maquiladora plants in panel (a), productivity rose 45% from 1994 (when Mexico joined NAFTA) to 2003, a compound growth rate of 4.1% per year for more than nine years. For the non-maquiladora plants, productivity rose overall by 25% from 1994 to 2003, 2.5% per year. The difference between these two numbers, which is 1.6% per year, is an estimate of the impact of NAFTA on the productivity of the maquiladora plants over and above the increase in productivity that occurred in the rest of Mexico.

Real Wages and Incomes Real wages in the maquiladora and non-maquiladora plants are shown in panel (b) of Figure 6-8. From 1994 to 1997, there was a fall of more than 20% in real wages in both sectors, despite a rise in productivity in the nonmaquiladora sector. This fall in real wages is not what we expect from the monopolistic competition model, so why did it occur?

Explain how the crisis made it difficult to assess the impact of NAFTA itself for a long time.

Shortly after Mexico joined NAFTA, it suffered a financial crisis that led to a large devaluation of the peso. It would be incorrect to attribute the peso crisis to Mexico’s joining NAFTA, even though both events occurred the same year. Prior to 1994 Mexico followed a fixed exchange-rate policy, but in late 1994 it switched to a flexible exchange-rate regime instead, and the peso devalued to much less than its former fixed value. Details about exchange-rate regimes and the reasons for switching from a fixed to flexible exchange rate are covered in international macroeconomics. For now, the key idea is that when the peso’s value falls, it becomes more expensive for Mexico to import goods from the United States because the peso price of imports goes up. The Mexican consumer price index also goes up, and as a result, real wages for Mexican workers fall.

183

The maquiladora sector, located beside the U.S. border, was more susceptible to the exchange-rate change and did not experience much of a gain in productivity over that period because of the increased cost of inputs imported from the United States. Workers in both the maquiladora and non-maquiladora sectors had to pay higher prices for imported goods, which is reflected in higher Mexican consumer prices. So the decline in real wages for workers in both sectors is similar. This decline was short-lived, however, and real wages in both sectors began to rise again in 1998. By 2003 real wages in both sectors had risen to nearly equal their value in 1994. This means that workers in Mexico did not gain or lose because of NAFTA on average: the productivity gains were not shared with workers, which is a disappointing finding, but real wages at least recovered from the effects of the peso crisis.

The picture is somewhat better if instead of real wages, we look at real monthly income, which includes higher-income employees who earn salaries rather than wages.7 In panel (b), for the non-maquiladora sector, the data on real wages and real monthly income move together closely. But in the maquiladora sector, real monthly incomes were indeed higher in 2003 than in 1994, indicating some gains for workers in the manufacturing plants most affected by NAFTA. This conclusion is reinforced by other evidence from Mexico, which shows that higher-income workers fared better than unskilled workers in the maquiladora sector and better than workers in the rest of Mexico.8 From this evidence, the higher-income workers in the maquiladora sector gained most from NAFTA in the long run.

Reflecting the increase in productivity mentioned above.

Adjustment Costs in Mexico When Mexico joined NAFTA, it was expected that the short-run adjustment costs would fall especially hard on the agricultural sector in Mexico, such as the corn industry, because it would face strong import competition from the United States. For that reason, the tariff reductions in agriculture were phased in over 15 years. The evidence to date suggests that the farmers growing corn in Mexico did not suffer as much as was feared.9 There were several reasons for this outcome. First, the poorest farmers do not sell the corn they grow but consume it themselves and buy any extra corn they need. These farmers benefited from cheaper import prices for corn from the United States. Second, the Mexican government was able to use subsidies to offset the reduction in income for other corn farmers. Surprisingly, the total production of corn in Mexico rose following NAFTA instead of falling.

Turning to the manufacturing sector, we should again distinguish the maquiladora and non-maquiladora plants. For the maquiladora plants, employment grew rapidly following NAFTA, from 584,000 workers in 1994 to a peak of 1.29 million workers in 2000. After that, however, the maquiladora sector entered a downturn, due to several factors: the United States entered a recession, reducing demand for Mexican exports; China was competing for U.S. sales by exporting products similar to those sold by Mexico; and the Mexican peso became overvalued, making it difficult to export abroad. For all these reasons, employment in the maquiladora sector fell after 2000, to 1.1 million workers in 2003. It is not clear whether we should count this decline in employment as a short-run adjustment cost due to NAFTA, nor is it clear how long it will take the maquiladora sector to recover. What is apparent is that the maquiladora sector faces increasing international competition (not all due to NAFTA), which can be expected to raise the volatility of its output and employment, and that volatility can be counted as a cost of international trade for workers who are displaced.

184

Gains and Adjustment Costs for the United States Under NAFTA

Studies on the effects of NAFTA on the United States have not estimated its effects on the productivity of American firms, perhaps because Canada and Mexico are only two of many export markets for the United States, and it would be hard to identify the impact of their tariff reductions. Instead, to measure the long-run gains from NAFTA and other trade agreements, researchers have estimated the second source of gains from trade: the expansion of import varieties available to consumers. For the United States, we will compare the long-run gains to consumers from expanded product varieties with the short-run adjustment costs from exiting firms and unemployment.

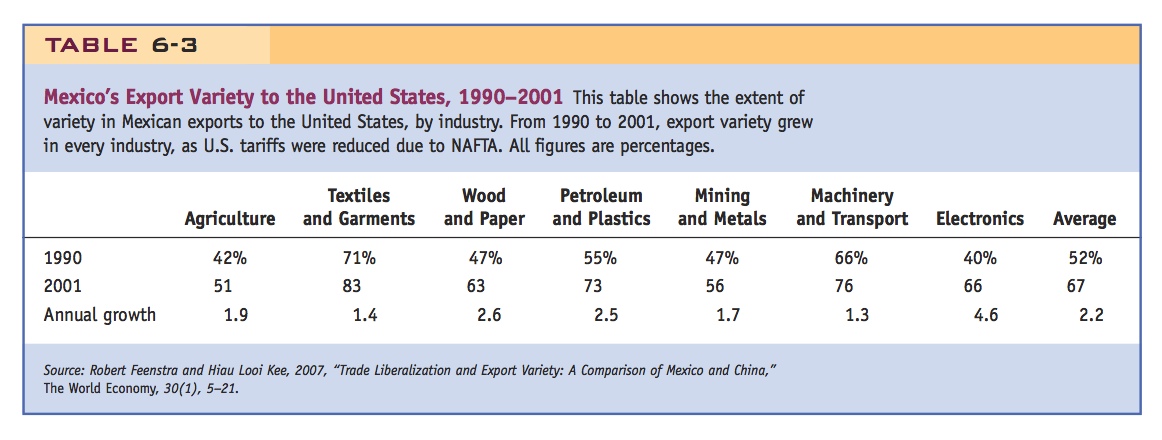

Expansion of Variety to the United States To understand how NAFTA affected the range of products available to American consumers, Table 6-3 shows the variety of goods Mexico exported to the United States in 1990 and 2001. To interpret these numbers, start with the 1990 export variety in agriculture of 42%. That figure means that 42% of all the agricultural products the United States imported in 1990, from any country, also came from Mexico. For instance, avocados, bananas, cucumbers, and tomatoes imported from various Central or South American countries were also imported to the United States from Mexico. Measuring the variety of products Mexico exported to the United States does not take into account the amount that Mexico sells of each product; rather, it counts the number of different types of products Mexico sells to the United States as compared with the total number of products the United States imports from all countries.

185

From 1990 to 2001, the range of agricultural products that Mexico exported to the United States expanded from 42 to 51%. That compound growth rate of 1.9% per year is close to the average annual growth rate for export variety in all industries shown in the last column of Table 6-3, which is 2.2% per year. Export variety grew at a faster rate in the wood and paper industry (with a compound growth rate of 2.6% per year), petroleum and plastics (2.5% growth), and electronics (4.6% growth). The industries in which there has traditionally been a lot of trade between the United States and Mexico—such as machinery and transport (including autos) and textiles and garments—have slower growth in export variety because Mexico was exporting a wide range of products in these industries to the United States even before joining NAFTA.

The punchline.

The increase in the variety of products exported from Mexico to the United States under NAFTA is a source of gains from trade for American consumers. The United States has also imported more product varieties over time from many other countries, too, especially developing countries. According to one estimate, the total number of product varieties imported into the United States from 1972 to 2001 has increased by four times. Furthermore, that expansion in import variety has had the same beneficial impact on consumers as a reduction in import prices of 1.2% per year.10 That equivalent price reduction is a measure of the gains from trade due to the expansion of varieties exported to the United States from all countries.

Unfortunately, we do not have a separate estimate of the gains from the growth of export varieties from Mexico alone, which averages 2.2% per year from Table 6-3. Suppose we use the same 1.2% price reduction estimate for Mexico that has been found for all countries. That is, we assume that the growth in export variety from Mexico leads to the same beneficial impact on U.S. consumers as a reduction in Mexican import prices of 1.2% per year, or about one-half as much as the growth in export variety itself. In 1994, the first year of NAFTA, Mexico exported $50 billion in merchandise goods to the United States and by 2001 this sum had grown to $131 billion. Using $90 billion as an average of these two values, a 1.2% reduction in the prices for Mexican imports would save U.S. consumers $90 billion · 1.2% = $1.1 billion per year. We will assume that all these savings are due to NAFTA, though even without NAFTA, there would likely have been some growth in export variety from Mexico.

It is crucial to realize that these consumer savings are permanent and that they increase over time as export varieties from Mexico continue to grow. Thus, in the first year of NAFTA, we estimate a gain to U.S. consumers of $1.1 billion; in the second year a gain of $2.2 billion, equivalent to a total fall in prices of 2.4%; in the third year a gain of $3.3 billion; and so on. Adding these up over the first nine years of NAFTA, the total benefit to consumers was $49.5 billion, or an average of $5.5 billion per year. In 2003, the tenth year of NAFTA, consumers would gain by $11 billion as compared with 1994. This gain will continue to grow as Mexico further increases the range of varieties exported to the United States.

186

Adjustment Costs in the United States Adjustment costs in the United States come as firms exit the market because of import competition and the workers employed by those firms are temporarily unemployed. One way to measure that temporary unemployment is to look at the claims under the U.S. Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) provisions. The TAA program offers assistance to workers in manufacturing who lose their jobs because of import competition. As we discussed in Chapter 3, the North American Free Trade Agreement included a special extension of TAA to workers laid off due to import competition because of NAFTA.

By looking at claims under that program, we can get an idea of the unemployment caused by NAFTA, one of the short-run costs of the agreement. From 1994 to 2002, some 525,000 workers, or about 58,000 per year, lost their jobs and were certified as adversely affected by trade or investment with Canada or Mexico under the NAFTA-TAA program.11 As a result, these workers were entitled to additional unemployment benefits. This number is probably the most accurate estimate we have of the temporary unemployment caused by NAFTA.

How large is the displacement of 58,000 workers per year due to NAFTA? We can compare this number with overall job displacement in the United States. Over the three years from January 1999 to December 2001, 4 million workers were displaced, about one-third of whom were in manufacturing. So the annual number of workers displaced in manufacturing was 4 million  = 444,000 workers per year. Thus, the NAFTA layoffs of 58,000 workers were about 13% of the total displacement in manufacturing, which is a substantial amount.

= 444,000 workers per year. Thus, the NAFTA layoffs of 58,000 workers were about 13% of the total displacement in manufacturing, which is a substantial amount.

Rather than compare the displacement caused by NAFTA with the total displacement in manufacturing, however, we can instead evaluate the wages lost by displaced workers and compare this amount with the consumer gains. In Chapter 3 (see Application: Manufacturing and Services), we learned that about 56% of workers laid off in manufacturing during the 2009–2011 period were reemployed within three years (by January 2012). That estimate of the fraction of workers reemployed within three years has been somewhat higher—66%—during earlier recessions. Some workers are reemployed in less than three years; for some, it takes longer. To simplify the problem, suppose that the average length of unemployment for laid-off workers is three years.12 Average yearly earnings for production workers in manufacturing were $31,000 in 2000, so each displaced worker lost $93,000 in wages (three times the workers’ average annual income).13 Total lost wages caused by displacement would be 58,000 workers displaced per year times $93,000, or $5.4 billion per year during the first nine years of NAFTA.

These private costs of $5.4 billion are nearly equal to the average welfare gains of $5.5 billion per year due to the expansion of import varieties from Mexico from 1994 to 2002, as computed previously. But the gains from increased product variety continue and grow over time as new imported products become available to American consumers. Recall from the previous calculation that the gains from the ongoing expansion of product varieties from Mexico were $11 billion in 2003, the tenth year of NAFTA, or twice as high as the $5.4 billion costs of adjustment. As the consumer gains continue to grow, adjustment costs due to job losses fall. Thus, the consumer gains from increased variety, when summed over years, considerably exceed the private losses from displacement. This outcome is guaranteed to occur because the gains from expanded import varieties occur every year that the imports are available, whereas labor displacement is a temporary phenomenon.

187

The calculation we have made shows that the gains to U.S. consumers from greater import variety from Mexico, when summed over time, are more than the private costs of adjustment. In practice, the actual compensation received by workers is much less than their costs of adjustment. In 2002 the NAFTA–TAA program was consolidated with the general TAA program in the United States, so there is no further record of layoffs as a result of NAFTA. Under the Trade Act of 2002, the funding for TAA was increased from $400 million to $1.2 billion per year and some other improvements to the program were made, such as providing a health-care subsidy for laid-off workers. In addition, as part of the jobs stimulus bill signed by President Obama on February 17, 2009, workers in the service sector (as well as farmers) who lose their jobs due to trade can now also apply for TAA benefits, as was discussed in Chapter 3. It would be desirable to continue to expand the TAA program to include more workers who face layoffs due to increased global competition.

Given how large the tariff reductions for Mexico were, it seems surprising that it has benefited so little. But the outcome is confused by the peso crisis, still.

Summary of NAFTA In this section, we have been able to measure, at least in part, the long-run gains and short-run costs from NAFTA for Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The monopolistic competition model indicates two sources of gains from trade: the rise in productivity due to expanded output by surviving firms, which leads to lower prices, and the expansion in the overall number of varieties of products available to consumers with trade, despite the exit of some firms in each country. For Mexico and Canada, we measured the long-run gains by the improvement in productivity for exporters as compared with other manufacturing firms. For the United States, we measured the long-run gains using the expansion of varieties from Mexico, and the equivalent drop in price faced by U.S. consumers. It is clear that for Canada and the United States, the long-run gains considerably exceed the short-run costs. The picture is less optimistic for Mexico because the gains have not been reflected in the growth of real wages for production workers (due in part to the peso crisis). The real earnings of higher-income workers in the maquiladora sector have risen, however, so they have been the principal beneficiaries of NAFTA so far.