2 Tariffs with Foreign Monopoly

1. Objectives: Analyze effects of a tariff on a foreign monopolist exporter; similar to the large-country case in Chapter 8.

2. Foreign Monopoly

For simplicity, assume the Foreign firm sells only in the Home market and that there is no Home competitor.

a. Free-Trade Equilibrium

Foreign firm exports the quantity where MR = MC (assumed constant), so P > MC.

b. Effect of a Tariff on Home Price

The tariff raises MC. Exports fall. Price increases, but by less than the tariff (assuming that MR is steeper than demand), so the price net-of-tariff falls: Home enjoys an improvement of its terms-of-trade.

c. Summary: Intuitively, the firm allows the Home price to increase by less than the tariff, in order to reduce the reduction in exports.

d. Effect of the Tariff on Home Welfare: Consumer surplus falls, tariff revenue increases, (with no effect on Home producer surplus), but there is a net welfare loss. Part of the tariff is being paid by the Foreign firm because the net-of-tariff price it receives has decreased. This is a TOT gain similar to that in Chapter 8. It follows that, if the gain in tariff revenue from the Foreign firm exceeds the deadweight loss, then the tariff will increase Home welfare; there is an optimal tariff here too.

So far in this chapter, we have studied the effects of a tariff or quota under Home monopoly. For simplicity, we have focused on the case in which the Home country is small, meaning that the world price is fixed. Let us now examine a different case, in which we treat the Foreign exporting firm as a monopoly. We will show that applying a tariff under a Foreign monopoly leads to an outcome similar to that of the large-country case in the previous chapter; that is, the tariff will lower the price charged by the Foreign exporter. In contrast to the small-country case, a tariff may now benefit the Home country.

Foreign Monopoly

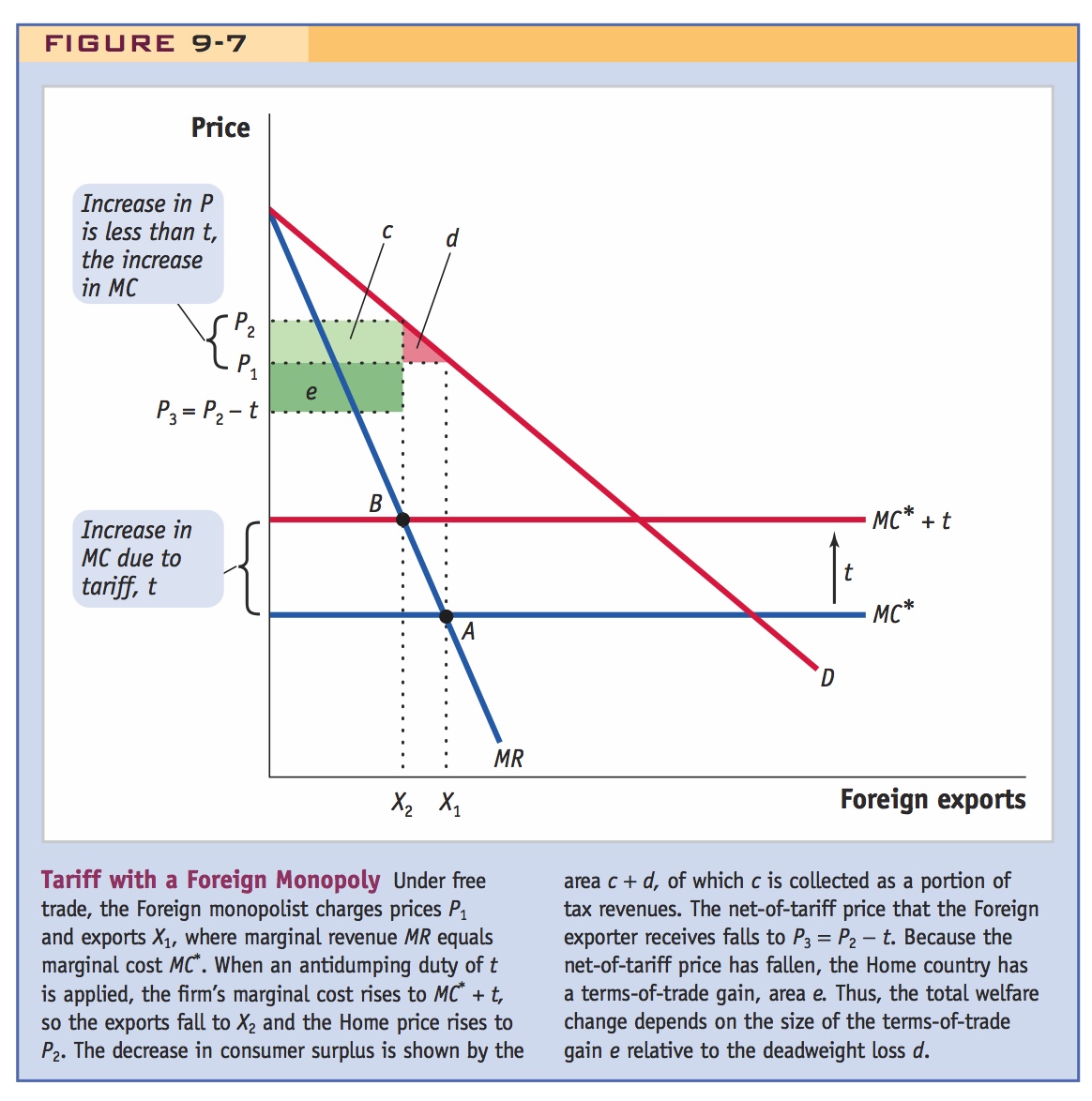

To focus our attention on the Foreign monopolist selling to the Home market, we will assume that there is no competing Home firm, so the Home demand D in Figure 9-7 is supplied entirely by exports from the Foreign monopolist. This assumption is not very realistic because normally a tariff is being considered when there is also a Home firm. But ignoring the Home firm will simplify our analysis while still helping us to understand the effect of an imperfectly competitive Foreign exporter.

Free-Trade Equilibrium In addition to the Home demand of D in Figure 9-7, we also show Home marginal revenue of MR. Under free trade, the Foreign monopolist maximizes profits in its export market where Home marginal revenue MR equals Foreign marginal cost MC*, at point A in Figure 9-7. It exports the amount X1 to the Home market and charges the price of P1.

They are so habituated to the linear case that this might require a little explanation.

Effect of a Tariff on Home Price If the Home country applies an import tariff of t dollars, then the marginal cost for the exporter to sell in the Home market increases to MC* + t. With the increase in marginal costs, the new intersection with marginal revenue occurs at point B in Figure 9-7, and the import price rises to P2.

Under the case we have drawn in Figure 9-7, where the MR curve is steeper than the demand curve, the increase in price from P1 to P2 is less than the amount of the tariff t. In other words, the vertical rise along the MR curve caused by the tariff (the vertical distance from point A to B, which is the tariff amount) corresponds to a smaller vertical rise moving along the demand curve (the difference between P1 and P2). In this case, the net-of-tariff price received by the Foreign exporter, which is P3 = P2 − t, has fallen from its previous level of P1 because the price rises by less than the tariff. Since the Home country is paying a lower net-of-tariff price P3 for its import, it has experienced a terms-of-trade gain as a result of the tariff.

292

Highlight this analogy. Use it to infer that there must also be a TOT gain to partially offset the loss in consumer surplus.

The effect of the tariff applied against a Foreign monopolist is similar to the effect of a tariff imposed by a large country (analyzed in the previous chapter). There we found that a tariff would lower the price charged by Foreign firms because the quantity of exports decreased, so Foreign marginal costs also fell. Now that we have assumed a Foreign monopoly, we get the same result but for a different reason. The marginal costs of the monopolist are constant at MC* in Figure 9-7, or MC* + t including the tariff. The rise in marginal costs from the tariff leads to an increase in the tariff-inclusive Home price as the quantity of Home imports falls, but the monopolist chooses to increase the Home price by less than the full amount of the tariff. In that way, the quantity exported to Home does not fall by as much as it would if the Foreign firm increased its price by the full amount of the tariff. So, the Foreign firm is making a strategic decision to absorb part of the tariff itself (by lowering its price from P1 to P3) and pass through only a portion of the tariff to the Home price (which rises from P1 to P2).

Summary To preserve its sales to Home, the Foreign monopolist chooses to increase the Home price by less than the amount of the tariff. This result depends on having MR steeper than D, as shown in Figure 9-7. It is not necessarily the case that MR is steeper than D for all demand curves, but this is usually how we draw them. In the case of a straight-line demand curve such as the one drawn in Figure 9-7, for example, the marginal revenue curve is exactly twice as steep as the demand curve.6 In this case, the Home import price rises by exactly half of the tariff amount, and the Foreign export price falls by exactly half of the tariff amount.

293

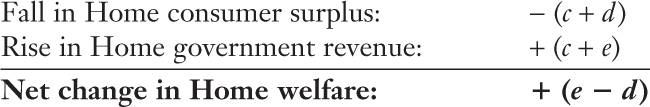

Effect of the Tariff on Home Welfare With the rise in the Home price from P1 to P2, consumers are worse off. The decline in consumer surplus equals the area between the two prices and to the left of the demand curve, which is (c + d) in Figure 9-7. The increase in the Home price would in principle benefit Home firms, but we have assumed for simplicity that there is no Home producer, so we do not need to keep track of the change in Home producer surplus. We do need to take account of tariff revenue collected by the Home government, however. Tariff revenue equals the amount of the tariff t times Foreign exports X2, which is area (c + e). Therefore, the effect of the tariff on Home welfare is

We can interpret the area e as the terms-of-trade gain for the Home country, whereas the area d is the deadweight loss from the tariff. If the terms-of-trade gain exceeds the deadweight loss, e > d, then Home gains overall by applying a tariff, similar to the result we found for a large country in the previous chapter. As we discussed there, we can expect the terms-of-trade gain to exceed the deadweight loss when the tariff is small, so that Home welfare initially rises for small tariffs. Welfare then reaches some maximum level and then falls as the tariff is increased beyond its optimal level. The same results apply when a tariff is placed against a Foreign monopolist, provided that the marginal revenue curve is steeper than demand, as we have assumed.

To illustrate how a tariff can affect the prices charged by a Foreign monopolist in practice, we once again use the automobile industry as an example. Because there are a small number of firms in that industry, it is realistic to expect them to respond to a tariff in the way that a Foreign monopolist would.

Do foreign exporters actually absorb part of the tariff in order to reduce the increase in Home prices? Case study: U.S. tariff of 25 percent on Japanese trucks since the 1980s. Only about 60 percent of the tariff was passed through to American consumers; the rest was absorbed by Japanese automakers. There is a substantial TOT benefit, so this is an example of a strategic trade policy that might improve U.S. welfare.

This is a great story to tell in class.

Import Tariffs on Japanese Trucks

We have found that in the case of a Foreign monopolist, Home will experience a terms-of-trade gain from a small tariff. The reason for this gain is that the Foreign firm will lower its net-of-tariff price to avoid too large an increase in the price paid by consumers in the importing country. To what extent do Foreign exporters actually behave that way?

To answer this question, we can look at the effects of the 25% tariff on imported Japanese compact trucks imposed by the United States in the early 1980s and still in place today. The history of how this tariff came to be applied is an interesting story. Recall from the application earlier in the chapter that in 1980 the United Automobile Workers and Ford Motor Company applied for a tariff under Article XIX of the GATT and Section 201 of U.S. trade law. They were turned down for the tariff, however, because the International Trade Commission determined that the U.S. recession was a more important cause of injury in the auto industry than growing imports. For cars, the “voluntary” export restraint (VER) with Japan was pursued. But for compact trucks imported from Japan, it turned out that another form of protection was available.

294

At that time, most compact trucks from Japan were imported as cab/chassis with some final assembly needed. These were classified as “parts of trucks,” which carried a tariff rate of only 4%. But another category of truck—“complete or unfinished trucks”—faced a tariff rate of 25%. That unusually high tariff was a result of the “chicken war” between the United States and West Germany in 1962. At that time, Germany joined the European Economic Community (EEC) and was required to adjust its external tariffs to match those of the other EEC countries. This adjustment resulted in an increase in its tariff on imported U.S. poultry. In retaliation, the United States increased its tariffs on trucks and other products, so the 25% tariff on trucks became a permanent item in the U.S. tariff code.

That tariff created an irresistible opportunity to reclassify the Japanese imports and obtain a substantial increase in the tariff, which is exactly what the U.S. Customs Service did with prodding from the U.S. Congress. Effective August 21, 1980, imported cab/chassis “parts” were reclassified as “complete or unfinished” trucks. This reclassification raised the tariff rate on all Japanese trucks from 4% to 25%, which remains in effect today.

How did Japanese exporters respond to the tariff? According to one estimate, the tariff on trucks was only partially reflected in U.S. prices: of the 21% increase, only 12% (or about 60% of the increase) was passed through to U.S. consumer prices; the other 9% (or about 40% of the increase) was absorbed by Japanese producers.7 Therefore, this tariff led to a terms-of-trade gain for the United States, as predicted by our theory: for a straight-line demand curve (as in Figure 9-7), marginal revenue is twice as steep, and the tariff will lead to an equal increase in the Home import price and decrease in the Foreign export price.8 The evidence for Japanese trucks is not too different from what we predict in that straight-line case.

Notice that the terms-of-trade gain from the tariff applied on a Foreign monopolist is similar to the terms-of-trade gain from a tariff applied by a “large” country, as we discussed in the previous chapter. In both cases, the Foreign firm or industry absorbs part of the tariff by lowering its price, which means that the Home price rises by less than the full amount of the tariff. If the terms-of-trade gain, measured by the area e in Figure 9-7 exceed the deadweight loss d, then the Home country gains from the tariff. This is our first example of strategic trade policy that leads to a potential gain for Home.

In principle, this potential gain arises from the tariff that the United States has applied on imports of compact trucks, and that is still in place today. But some economists feel that this tariff has the undesirable side effect of encouraging the U.S. automobile industry to focus on the sales of trucks, since compact trucks have higher prices because of the tariff.9 That strategy by U.S. producers can work when gasoline prices are low, so consumers are willing to buy trucks. At times of high prices, however, consumers instead want fuel-efficient cars, which have not been the focus of the American industry. So high fuel prices can lead to a surge in imports and fewer domestic sales, exactly what happened after the oil price increase of 1979 and again in 2008, just before the financial crisis. Some industry experts believe that these factors contributed to the losses faced by the American industry during the crisis, as explained in Headlines: The Chickens Have Come Home to Roost.

...and a great example to make the theory concrete.

295

The article recounts the strange history of the tariff on Japanese trucks, and argues that it has perverse effects on the U.S. auto industry.

The Chickens Have Come Home to Roost

This article discusses the history of the 25% tariff that still applies to U.S. imports of lightweight trucks. The author argues that this tariff caused some of the difficulties in the U.S. automobile industry today.

Although we call them the big three automobile companies, they have basically specialized in building trucks. This left them utterly unable to respond when high gas prices shifted the market towards hybrids and more fuel efficient cars.

One reason is that Americans like to drive SUVs, minivans and small trucks when gasoline costs $1.50 to $2.00 a gallon. But another is that the profit margins have been much higher on trucks and vans because the US protects its domestic market with a twenty-five percent tariff. By contrast, the import tariff on regular automobiles is just 2.5 percent and US duties from tariffs on all imported goods are just one percent of the overall value of merchandise imports. Since many of the inputs used to assemble trucks are not subject to tariffs anywhere near 25 percent—US tariffs on all goods average only 3.5 percent—the effective protection and subsidy equivalent of this policy has been huge.

It is no wonder much of the initial foray by Japanese transplants to the US involved setting up trucks assembly plants, no wonder that Automakers only put three doors on SUVs so they can qualify as vans and no wonder that Detroit is so opposed to the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement that would eventually allow trucks built in Korea Duty-Free access to the US market.

What accounts for this distinctive treatment of trucks? An accident of history that shows how hard it is for the government to withdraw favors even when they have no sound policy justification.

It all comes down to the long forgotten chicken wars of the 1960s. In 1962, when implementing the European Common Market, the Community denied access to US chicken producers. In response after being unable to resolve the issue diplomatically, the US responded with retaliatory tariffs that included a twenty five percent tariffs on trucks that was aimed at the German Volkswagen Combi-Bus that was enjoying brisk sales in the US.

Since the trade (GATT) rules required that retaliation be applied on a nondiscriminatory basis, the tariffs were levied on all truck-type vehicles imported from all countries and have never been removed. Over time, the Germans stopped building these vehicles and today the tariffs are mainly paid on trucks coming from Asia. The tariffs have bred bad habits, steering Detroit away from building highquality automobiles towards trucks and trucklike cars that have suddenly fallen into disfavor.

If Congress wants an explanation for why the big three have been so uncompetitive it should look first at the disguised largess it has been providing them with for years. It has taken a long time—nearly 47 years—but it seems that eventually the chickens have finally come home to roost.

Source: Robert Lawrence, guest blogger on Dani Rodrik’s weblog, posted May 4, 2009. http://www.rodrik.typepad.com/dani_rodriks_weblog/2009/05/the-chickens-have-come-home-to-roost.html.

296