3 Dumping

Imperfect competition may permit price discrimination. Practicing price discrimination between countries requires the markets to be segmented. Dumping occurs if a firm sets a price abroad that is either lower than its price at home, or lower than its average cost. Dumping is discouraged by WTO, but common.

a. Discriminating Monopoly

Foreign firm has monopoly power abroad, but faces a perfectly competitive market at Home.

b. Equilibrium Condition

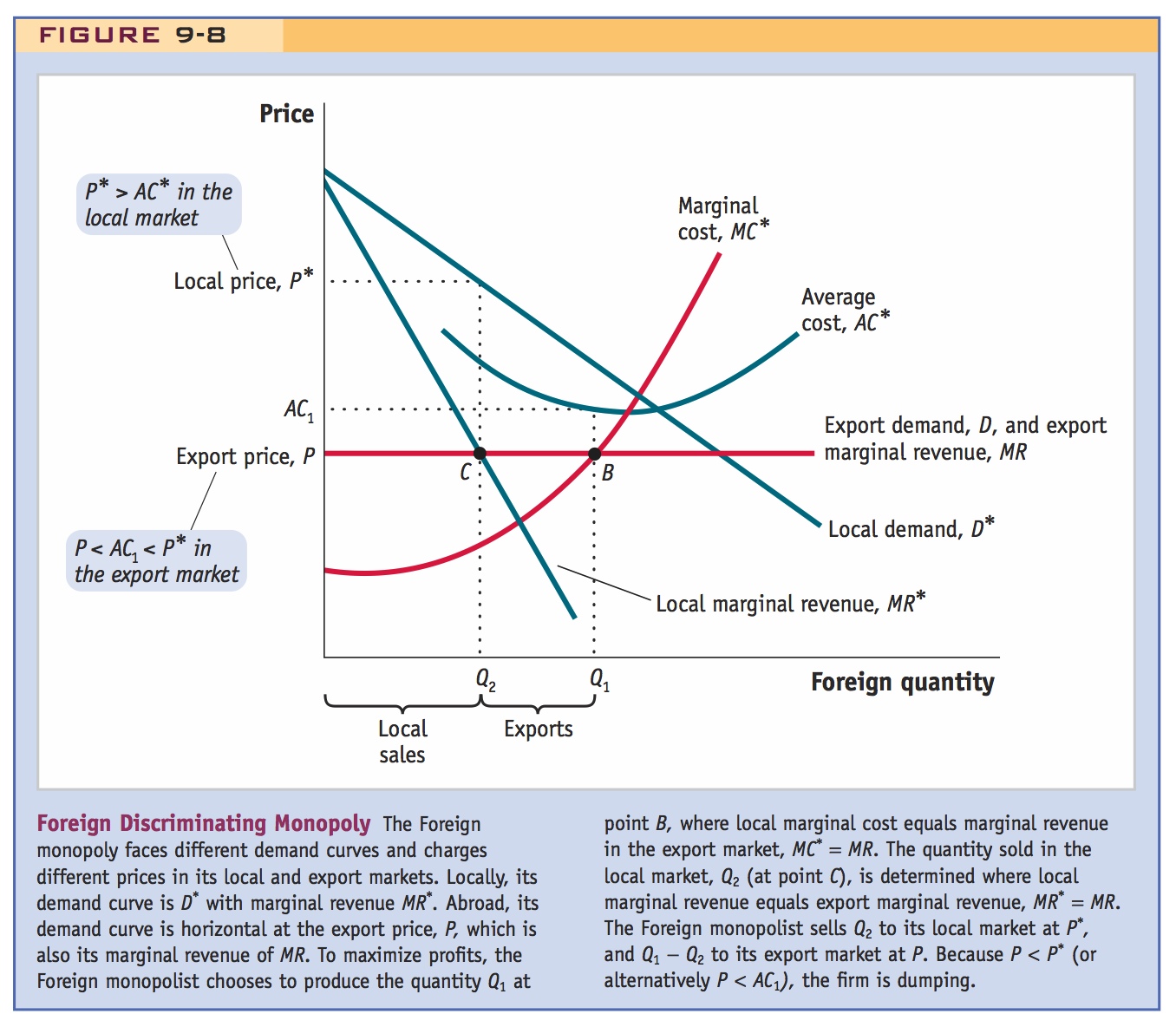

Firm produces where MR = MR* = MC*, as illustrated in Figure 9-8. It sells some to Foreign consumers, and exports the rest to Home.

c. The Profitability of Dumping

Since demand is more elastic abroad, the firm charges a lower price at Home than in Foreign. It is dumping. It is also possible for the export price to be lower than average cost.

With imperfect competition, firms can charge different prices across countries and will do so whenever that pricing strategy is profitable. Recall that we define imperfect competition as the firm’s ability to influence the price of its product. With international trade, we extend this idea: not only can firms charge a price that is higher than their marginal cost, they can also choose to charge different prices in their domestic market than in their export market. This pricing strategy is called price discrimination because the firm is able to choose how much different groups of customers pay. To discriminate in international trade, there must be some reason that consumers in the high-price market cannot import directly from the low-cost market; for example, that reason could be transportation costs or tariffs between the markets.

Dumping occurs when a foreign firm sells a product abroad at a price that is either less than the price it charges in its local market, or less than its average cost to produce the product. Dumping is common in international trade, even though the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO) discourage this activity. Under the rules of the WTO, an importing country is entitled to apply a tariff any time a foreign firm dumps its product on a local market. Such a tariff is called an antidumping duty. We study antidumping duties in detail in the next section. In this section, we want to ask the more general question: Why do firms dump at all? It might appear at first glance that selling abroad at prices less than local prices or less than the average costs of production must be unprofitable. Is that really the case? It turns out the answer is no. It can be profitable to sell at low prices abroad, even at prices lower than average cost.

Emphasize that the markets must be segmented, and that this may be particularly plausible internationally.

Discriminating Monopoly To illustrate how dumping can be profitable, we use the example of a Foreign monopolist selling both to its local market and exporting to Home. As described previously, we assume that the monopolist is able to charge different prices in the two markets; this market structure is sometimes called a discriminating monopoly. The diagram for a Foreign discriminating monopoly is shown in Figure 9-8. The local demand curve for the monopolist is D*, with marginal revenue MR*. We draw these curves as downward-sloping for the monopolist because to induce additional consumers to buy its product, the monopolist lowers its price (downward-sloping D*), which decreases the revenue received from each additional unit sold (downward-sloping MR*).

Make sure students understand that demand in the firm's domestic market is less elastic than its export market; assuming export demand is perfectly elastic is a convenient polar case.

In the export market, however, the Foreign firm will face competition from other firms selling to the Home market. Because of this competition, the firm’s demand curve in the export market will be more elastic; that is, it will lose more customers by raising prices than it would in its local market. If it faces enough competition in its export market, the Foreign monopolist’s export demand curve will be horizontal at the price P, meaning that it cannot charge more than the competitive market price. If the price for exports is fixed at P, selling more units does not depress the price or the extra revenue earned for each unit exported. Therefore, the marginal revenue for exports equals the price, which is labeled as P in Figure 9-8.

Equilibrium Condition We can now determine the profit-maximizing level of production for the Foreign monopolist, as well as its prices in each market. For the discriminating monopoly, profits are maximized when the following condition holds:

MR = MR* = MC*

297

This equation looks similar to the condition for profit maximization for a single-market monopolist, which is marginal revenue equals marginal cost, except that now the marginal revenues should also be equal in the two markets.

We illustrate this equilibrium condition in Figure 9-8. If the Foreign firm produces quantity Q1, at point B, then the marginal cost of the last unit equals the export marginal revenue MR. But not all of the supply Q1 is exported; some is sold locally. The amount sold locally is determined by the equality of the firm’s local marginal revenue MR* with its export marginal revenue MR (at point C), and the equality of its local marginal cost MC* with MR (at point B). All three variables equal P, though the firm charges the price P* (by tracing up the Foreign demand curve) to its local consumers. Choosing these prices, the profit-maximization equation just given is satisfied, and the discriminating monopolist is maximizing profits across both markets.

The Profitability of Dumping The Foreign firm charges P* to sell quantity Q2 in its local market (from Q2, we go up to the local demand curve D* and across to the price). The local price exceeds the price P charged in the export market. Because the Foreign firm is selling the same product at a lower price to the export market, it is dumping its product into the export market.

298

Conclusion: The firm is dumping, according to both criteria. But ask them to depict case where the firm is dumping according to the price criterion and not by the AC criterion.

What about the comparison of its export price with average costs? At total production of Q1 at point B, the firm’s average costs are read off the average cost curve above that point, so average costs equal AC1, lower than the local price P* but higher than the export price P. Because average costs AC1 are above the export price P, the firm is also dumping according to this cost comparison. But we will argue that the Foreign firm still earns positive profits from exporting its good at the low price of P. To see why that is the case, we turn to a numerical example.

Numerical Example of Dumping

Suppose the Foreign firm has the following cost and demand data:

The profits earned from selling in its local market are

Notice that the average costs for the firms are

Now suppose that this firm sells an additional 10 units abroad, at the price of $15, which is less than its average cost of production. It is still worthwhile to sell these extra units because profits become

Profits have increased because the extra units are sold at $15 but produced at a marginal cost of $10, which is less than the price received in the export market. Therefore, each unit exported will increase profits by the difference between the price and marginal costs. Thus, even though the export price is less than average costs, profits still rise from dumping in the export market.