Chapter 13: Introduction

Visual Effects and Animation

13

CHAPTER

“If you can imagine it, we can make it.”

– John Dykstra, visual effects designer and Academy Award winner on many films, including Star Wars (1977), Stuart Little (1999), and Spider-Man (2002)

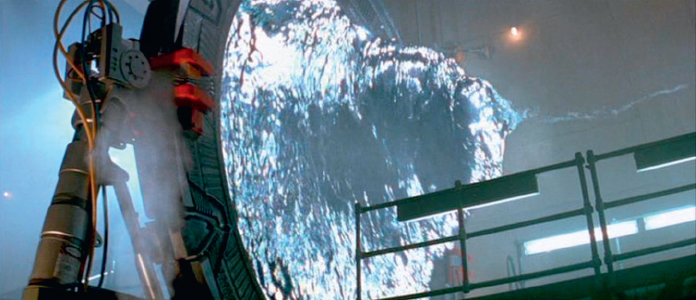

Stargate (1994)

KEY CONCEPTS

Visual effects (“VFX”) constitute an art form almost as old as the medium of filmmaking itself, and a discipline that has relevance for almost every major motion picture in the modern era. In modern filmmaking, the label has come to represent digital effects with a heavy reliance on computer-generated, -lit, and -composited imagery; more generally, however, the term refers to the creation and incorporation of any elements that cannot be captured during principal photography.

Visual effects (“VFX”) constitute an art form almost as old as the medium of filmmaking itself, and a discipline that has relevance for almost every major motion picture in the modern era. In modern filmmaking, the label has come to represent digital effects with a heavy reliance on computer-generated, -lit, and -composited imagery; more generally, however, the term refers to the creation and incorporation of any elements that cannot be captured during principal photography. Practical effects, called special effects these days, remain part of the picture in some cases—effects achieved in-camera using more traditional methods, including the use of models and miniatures or other effects, such as explosion, that are created live, on-set. But today, the combining of digital and nondigital elements into final shots is almost always done by computer.

Practical effects, called special effects these days, remain part of the picture in some cases—effects achieved in-camera using more traditional methods, including the use of models and miniatures or other effects, such as explosion, that are created live, on-set. But today, the combining of digital and nondigital elements into final shots is almost always done by computer. A solid understanding of the basics of computer-generated imagery (CGI) is crucial to understanding modern visual effects. The processes, workflow, and tools for doing CGI work are now everyday elements in the modern filmmaking paradigm. Some of the creative principles of computer animation, however, are no different from the time-honored concepts of traditional hand-drawn animation.

A solid understanding of the basics of computer-generated imagery (CGI) is crucial to understanding modern visual effects. The processes, workflow, and tools for doing CGI work are now everyday elements in the modern filmmaking paradigm. Some of the creative principles of computer animation, however, are no different from the time-honored concepts of traditional hand-drawn animation. Character animation is an art form that dates back to the beginning of modern film—an art form in which the animator “acts” by putting an emotional performance into a character that would not otherwise exist. In the digital world, characters can range from cartoony to photorealistic, and be created using a variety of techniques, including hand-drawings, digital motion capture or performance capture techniques, and frame-by-frame performance animation methods.

Character animation is an art form that dates back to the beginning of modern film—an art form in which the animator “acts” by putting an emotional performance into a character that would not otherwise exist. In the digital world, characters can range from cartoony to photorealistic, and be created using a variety of techniques, including hand-drawings, digital motion capture or performance capture techniques, and frame-by-frame performance animation methods. Using digital elements requires you to carefully manage data during the visual effects process. This includes tracking data, using and sharing correct files, naming files correctly, and backing them up. The central requirement in this regard is to always protect original data so that you have pristine backup elements in the event you need them.

Using digital elements requires you to carefully manage data during the visual effects process. This includes tracking data, using and sharing correct files, naming files correctly, and backing them up. The central requirement in this regard is to always protect original data so that you have pristine backup elements in the event you need them.

In 1994, Jeffrey Okun had a close brush with getting fired while working as digital effects supervisor on Roland Emmerich’s film Stargate. Okun was responsible for designing the look of the mysterious Stargate portal that sits at the plot’s center—a portal that opens and closes for intergalactic travelers. Okun eventually came up with a basic look that Emmerich was excited about. But Okun says his blind spot was the fact that he couldn’t describe to Emmerich’s satisfaction what the Stargate would look like as it turned on and off.

“Roland hated about 150 ideas I had, but then I shot one more test—filming a three-foot diameter Plexiglas tube with iced tea in it, which I stirred with a drill with a piece of wood attached to get a nice, soft spin,” Okun, now a well-known industry visual effects supervisor, recalls.1 “Then I shot reflections of sun rays through the iced tea, which I could then pull out as a matte or use digital photography to add onto the [Stargate set]. When I showed Roland the footage, he was really excited about the stirring motion—the funnel, or the ‘strudel,’ as he called it. As you stirred it, it formed a ‘V’ in the water. He said that is what the Stargate should look like. He loved what we ended up with, but before that, I almost got fired because there was no real way for me to communicate what I was thinking in terms of organic things that you had seen before in the real world, but not in the way I had in mind—I had to show him.”

The point of Okun’s example is that the communication process with his director trumped any technology or technique he had at his disposal. He suggests that creativity, an understanding of real-world visuals, communication, and problem-solving skills are more important to achieving success in visual effects than technical proficiency. Industry professionals agree that the best visual effects training involves studying organic things in the real world in what Okun calls “an interactive way.” Indeed, famed visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston insists you won’t get far in manufacturing artificial shots “if you don’t understand what the final image is supposed to be in your head.”2

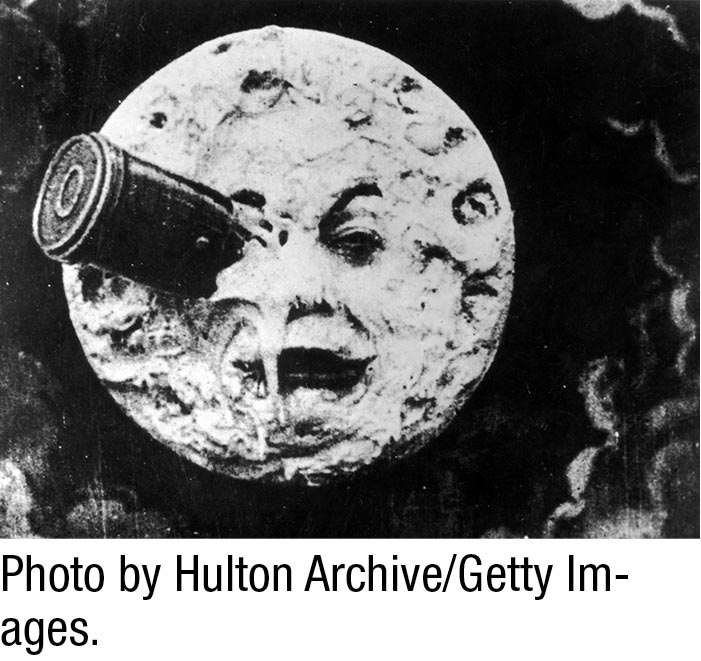

A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Visual effects wizards have been dazzling audiences ever since the legendary Georges Méliès essentially invented the concept of visual effects when he made 1902’s A Trip to the Moon. From Méliès to Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion animation tricks to the pioneering work of the original Star Wars visual effects team to Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs to industry-advancing achievements seen in Terminator 2, Matrix, Avatar, and Life of Pi, visual effects have been helping filmmakers tell stories effectively for generations. At their core, all effects emanate from a single need—to build images you can’t create during routine photography. Perhaps they are impossible to film in the real world, perhaps you can’t afford to do it, or perhaps they aren’t safe or logical to capture on-set. Whatever the reason, your solution will involve some part of the visual effects process.

The Visual Effects Society Award, designed as an homage to the pioneering, seminal visual effects created by George Méilès in 1902.

Thus, specific techniques are crucial to comprehend, particularly computer animation, as we will discuss later. Understand that we will use visual effects, or VFX, in this chapter as shorthand, since today, it is really an umbrella term that is largely built on the foundation of computer-generated imagery (CGI)—a term that incorporates the more specific functions of creating moving images in the computer. As you will discover, the creation of moving images in the computer is also a wider, general label that covers the more specific, but creatively different, disciplines of digital effects generally—the art of adding or combining digital imagery with other digital images or live-action images—and digital character animation, which is the art of creating acting performances for digital characters or creatures, giving them life and emotion.

The visual effects department has evolved into a filmmaking hub—almost all departments are connected to, or interact with, the visual effects unit. Today, members of a visual effects department will be on-set for testing and preproduction, as well as through principal and second-unit photography, and they will likely be involved in all aspects of postproduction. Visual effects are no longer a specialized process to worry about “later.”

This means that there is now more information than ever to digest regarding what visual effects are, how to create them, and how to use them effectively. Some of the technical nuance and science behind all this are things you will learn later in your education. For now, though, you can certainly grasp the fundamentals of how to create photo-realistic or near photo-realistic images outside of principal photography, and how to blend them with real-world images to create a seamless result. These basics will be the prime focus of this chapter.