Character Animation

Now that you have the technical overview of the basic steps in the computer-animation process, whatever software tools you use should allow you to create models and rig them with the controls and capabilities you will need as the animator to achieve story goals. But when it comes to character animation, manipulating any digital character to have emotional impact successfully will require much more than mere technical proficiency—it will require you to think like both an actor and an artist in order to merge several goals together in your creative work. Character animation, whether done by computer, by hand, or by photographing stop-motion puppets, is about one thing and one thing only—the illusion of life. Achieving this goal to a level sufficient for satisfying an audience depends far more on your ability to create and “perform” the character as an actor would, than on any of the mechanical techniques previously described.

PRINCIPLES OF ANIMATION

PRINCIPLES OF ANIMATION

If you are interested in character animation, it’s a good idea to read The Illusion of Life, by former Disney animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, which is still considered an animator’s bible. Among other things, Thomas and Johnston suggest 12 principles of character animation one should follow, involving character positioning, building anticipation into the action, overlapping action, and making sure acceleration follows the laws of physics.

Key Techniques

The first step in character animation is actually a question: Why do these characters need to be animated? Once you’re sure that the creation of an animated character is driven by the story, it’s important to understand what the digital character is thinking and feeling at a particular moment in the story—just like an actor. You will also need to know how to externalize that emotion with the tools at your disposal. To do that, you must determine the purpose of every single movement you intend to program your character with.

All this is precisely why experienced industry professionals routinely urge those who wish to be animators to take acting classes. They also suggest keeping a mirror at your desk so that you can see yourself physically acting out particular movements you want to put into your character. In addition, you should become an observer of others, sketching and photographing people and animals in movement, and taking note of movement in other movies or videos. Even if you are animating an alien or a monster, it will need to interact with some kind of environment and other characters in a way that the viewer needs to comprehend from his or her experiences in the real world. It’s also a good idea to watch classic 2D animation; after all, the goal for an emotional connection and movement the audience can accept and enjoy (and not be distracted by) is exactly the same whether you are using a computer or a pencil.

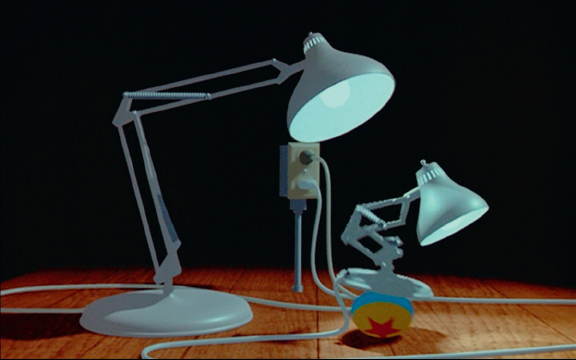

Pixar’s Luxo Jr. (1986) uses character animation to lend personality to a pair of desk lamps.

Learning all the techniques behind character animation takes years of hard work, but here are a few key principles based on ideas from longtime Disney animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston out of their seminal 1986 book on character animation, The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation, and also from Pixar founder John Lasseter:

Every movement of any body part needs to have a specific purpose and appear to the audience to occur out of some kind of thought process on the character’s part. The thought and personality of the character should impact its movement, and how the character physically acts should always help the audience understand what the character is thinking or feeling.

Every movement of any body part needs to have a specific purpose and appear to the audience to occur out of some kind of thought process on the character’s part. The thought and personality of the character should impact its movement, and how the character physically acts should always help the audience understand what the character is thinking or feeling. Leading with the eyes or head is an excellent technique for illustrating that the character’s upcoming motion is something it thought about first.

Leading with the eyes or head is an excellent technique for illustrating that the character’s upcoming motion is something it thought about first. The exception to the notion that the character should first think about an action is when the character is reacting instinctively to some unexpected force. In such cases, unless you are going for exaggerated movement, studying and comprehending real-world physics is an excellent way to illustrate the character’s response to an external action—falling down, flipping over, ducking instinctively, writhing in pain.

The exception to the notion that the character should first think about an action is when the character is reacting instinctively to some unexpected force. In such cases, unless you are going for exaggerated movement, studying and comprehending real-world physics is an excellent way to illustrate the character’s response to an external action—falling down, flipping over, ducking instinctively, writhing in pain. Mix it up—do not have the character act or move exactly the same way when in different emotional states. The gait of the walk, the facial expression, and so on, should be different when the character is happy, sad, bored, angry, and so forth.

Mix it up—do not have the character act or move exactly the same way when in different emotional states. The gait of the walk, the facial expression, and so on, should be different when the character is happy, sad, bored, angry, and so forth. Similarly, when animating multiple characters, do not have them all act and move the same way, unless a particular story point requires it. There needs to be the same kind of uniqueness in each character as there would be in real life.

Similarly, when animating multiple characters, do not have them all act and move the same way, unless a particular story point requires it. There needs to be the same kind of uniqueness in each character as there would be in real life. Timing is everything. Allow the audience to anticipate actions or prepare them for actions, and likewise give them time to react to actions. For example, a second action should start a fraction of a second before the preceding action has finished. This helps make sure there is continuity and that the audience’s attention will have no time to wander away.

Timing is everything. Allow the audience to anticipate actions or prepare them for actions, and likewise give them time to react to actions. For example, a second action should start a fraction of a second before the preceding action has finished. This helps make sure there is continuity and that the audience’s attention will have no time to wander away. As Lasseter says, “In every step of the production of your animation—the story, the design, the staging, the animation, the editing, the lighting, the sound, etc.—ask yourself why? Why is this here? Does it further the story? Does it support the whole?”7 Knowing why your character moves, he says, is much more important than knowing how to move it. If you take that as a guiding principle for character animation, you will be off to a solid start.

As Lasseter says, “In every step of the production of your animation—the story, the design, the staging, the animation, the editing, the lighting, the sound, etc.—ask yourself why? Why is this here? Does it further the story? Does it support the whole?”7 Knowing why your character moves, he says, is much more important than knowing how to move it. If you take that as a guiding principle for character animation, you will be off to a solid start.

Motion Capture

CAPTURING THE CAMERA

CAPTURING THE CAMERA

Camera movement itself can be mocapped by placing markers on a camera taping a performer, giving animators access to data of the camera’s exact movements in order to replicate them in the virtual world. On the Academy Award–nominated animated film, Surf’s Up (2007), this approach was taken to an entirely new level by allowing the film’s director to view the animation through a real camera viewfinder and then record the movements of the camera to create a “handheld” documentary feel to the camera’s movement.

In recent years, the art of character animation by computer has been greatly impacted by the proliferation of another digital breakthrough—the so-called motion-capture process, sometimes called performance capture. At the simplest level, motion capture—or mocap, as it is often called—is a process of using sensors and specialized cameras to record the movement of a living person or creature, translate those recordings to data, save that data, import it into a computer-animation system, and apply it to the digital controls for CGI characters to permit them to have more realistic movement. The process has been around for years and has become more popular as the technology has evolved, as demonstrated by James Cameron’s Avatar in 2009. That film advanced the art and science of the technique at the time, using motion capture to animate dozens of detailed digital characters for the entire movie, and breaking box-office records along the way. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) took mocap’s ability to portray highly believable creatures on a big screen even further, and the technique continues to play a growing role on major Hollywood films.

Indeed, mocap is relatively commonplace today and is almost ubiquitous in video games. Mocap’s rise certainly brings up issues regarding the role of the actor in the digital era, and how all-digital films can be made more efficiently in the future. Many directors certainly like it because it gives them the ability to “direct” animated characters down to the smallest, most nuanced movement. On the other hand, dedicated motion-capture hardware and the staging of mocap sessions can get expensive and often be technically complicated. Remember that mocap is not exactly “plug and play,” and should not be thought of as a shortcut; in fact, animators are frequently needed to tweak raw mocap movements in animated characters to meet a project’s specific needs, particularly those concerning facial capture—relying on mocap systems specifically designed to capture subtle motion of facial muscles.

FINDING AN ALTERNATIVE

FINDING AN ALTERNATIVE

In 2009, Zack Snyder’s superhero epic, Watchmen, featured almost 1,000 visual effects shots. For that giant-budget film, Snyder’s team concocted an ultracomplex methodology of transforming Billy Crudup, who played the big, blue Dr. Manhattan, into a realistic all-CGI character, whose very body was also a light source. They not only motion-captured Crudup’s movements but also used a special suit on him with LED lights to record light emitting from his body at the same time, and then combined that element with the computer-generated version of the character. But suppose you needed your own Dr. Manhattan and had no giant visual effects team and huge budget? Offer up alternative suggestions for ways to bring Dr. Manhattan to life on a student’s budget and timeline. Don’t worry about whether you would achieve the same level of quality as the Hollywood filmmakers. Just focus on methods you think might work, and list the tools and techniques you would incorporate. There is no right or wrong answer for this exercise—it’s designed to help you understand the importance of using creativity and ingenuity when faced with major challenges.

But no matter how you feel about those issues, mocap is a useful tool under certain conditions and a permanent part of the CGI industry. Indeed, many film schools and media centers now offer students and professionals motion-capture equipment and stages. As such, it will be useful for you to learn the basic aspects of the technique:

Outfit actors in special skin-tight suits, which have reflective markers or lights stitched into them at various locations, particularly at the joints. Set up special infrared camera systems on a specially configured stage to bounce light off the markers so that computer sensors can record the light patterns bouncing back and save that data to hard drives. Alternatively, in recent years, mocap suits have been developed that can work with high-quality video cameras without bouncing infrared light. In those cases, special software tools analyze the movement and light reflections involving an actor on a mocap stage direct from a video recording and interpolate that analysis into movement data.

Outfit actors in special skin-tight suits, which have reflective markers or lights stitched into them at various locations, particularly at the joints. Set up special infrared camera systems on a specially configured stage to bounce light off the markers so that computer sensors can record the light patterns bouncing back and save that data to hard drives. Alternatively, in recent years, mocap suits have been developed that can work with high-quality video cameras without bouncing infrared light. In those cases, special software tools analyze the movement and light reflections involving an actor on a mocap stage direct from a video recording and interpolate that analysis into movement data. Stage performances with actors in the mocap suits, asking them to go through motions specific to what the story calls for.

Stage performances with actors in the mocap suits, asking them to go through motions specific to what the story calls for. Typically, special computer software saves and analyzes the data and applies it to stick-figure, animated characters, allowing each figure to replicate the actor’s motion. The data is then mapped to the computer model’s digital controls, giving the animator control over those movements via animation software packages.

Typically, special computer software saves and analyzes the data and applies it to stick-figure, animated characters, allowing each figure to replicate the actor’s motion. The data is then mapped to the computer model’s digital controls, giving the animator control over those movements via animation software packages.

Tom Hanks in a motion-capture suit during production of The Polar Express (2004), alongside his finished performance from the final film.