module 30 Land Management Practices

We have seen that resources can be managed or they can be over-

Learning Objectives

After reading this module, you should be able to

explain specific land management practices for rangelands and forests.

describe contemporary problems in residential land use and some potential solutions.

Land management practices vary according to land use

Now that we have a basic picture of how public land is classified and of the relationship between public land use and management agencies in the United States, let’s turn to some of the specific issues involved in managing different types of public lands. Note that many of the management issues we discuss here apply to private lands as well.

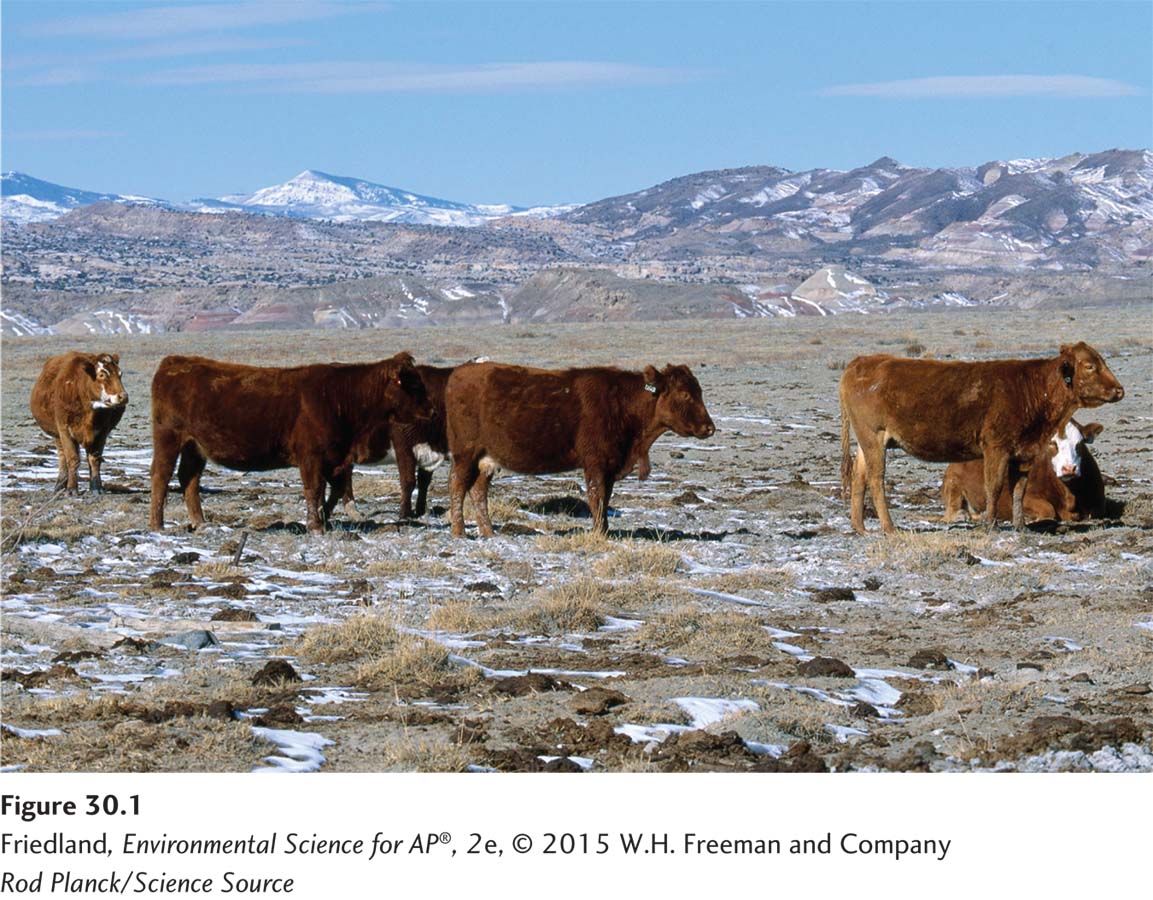

Rangelands

Rangeland A dry open grassland.

Rangelands are dry, open grasslands primarily used for the grazing of cattle, which is the most common use of land in the United States. Rangelands are semiarid ecosystems and are therefore particularly susceptible to fires and other environmental disturbances. When humans overuse rangelands, those rangelands can easily lose biodiversity.

Like most human activities, livestock grazing has mixed environmental effects. One environmental benefit of grazing is that ungulates—

Many environmental scientists argue that rangeland ecosystems are too fragile for multiple uses. Certain environmental organizations have suggested that as much as 55 percent of U.S. rangeland soils are in poor or very poor condition, due in large part to overgrazing. However, the BLM, which manages most public rangelands in the United States, has maintained that the percentage of poor or very poor soils is not nearly that high. Reconciling this difference is a challenge because of the many factors that influence how soil condition is determined.

The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 was passed to halt overgrazing. It converted federal rangelands from a commons into a permit-

The BLM focuses on mitigating the damage caused by grazing and considers “rangeland health” when it sets grazing guidelines. For example, state and regional rangeland managers are required to ensure healthy watersheds, maintain ecological processes such as nutrient cycles and energy flow, preserve water quality, maintain or restore habitats, and protect endangered species. However, because these managers are not given detailed guidance, and the BLM regulations do not require the involvement of environmental scientists, the managers have wide latitude to set their own guidelines and standards. As a result, BLM regulations are not consistently successful in preserving vulnerable rangeland ecosystems.

Forests

Forest Land dominated by trees and other woody vegetation and sometimes used for commercial logging.

Forests are dominated by trees and other woody vegetation. Approximately 73 percent of the forests used for commercial timber operations in the United States are privately owned. Many national forests were originally established to ensure a steady and reliable source of timber, and commercial logging companies are currently allowed to harvest U.S. national forests, usually in exchange for a royalty that is a percentage of their revenues. The federal government typically spends more money managing the timber program and building and maintaining logging roads than it receives from these royalties, essentially subsidizing the timber program as it does grazing on rangelands.

Timber Harvest Practices

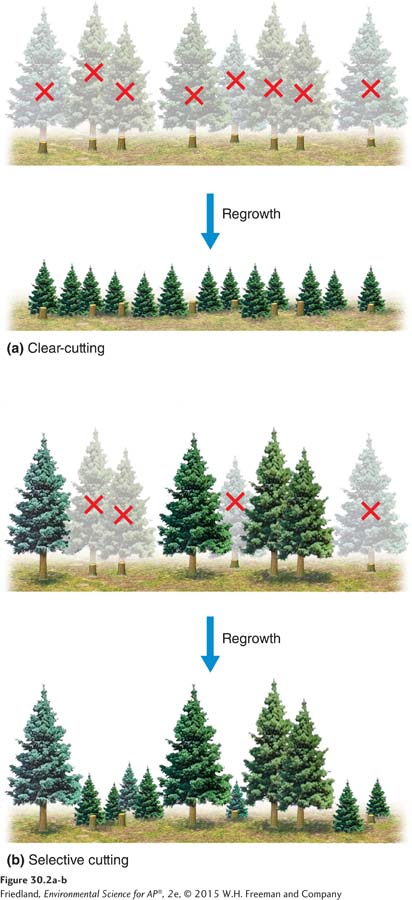

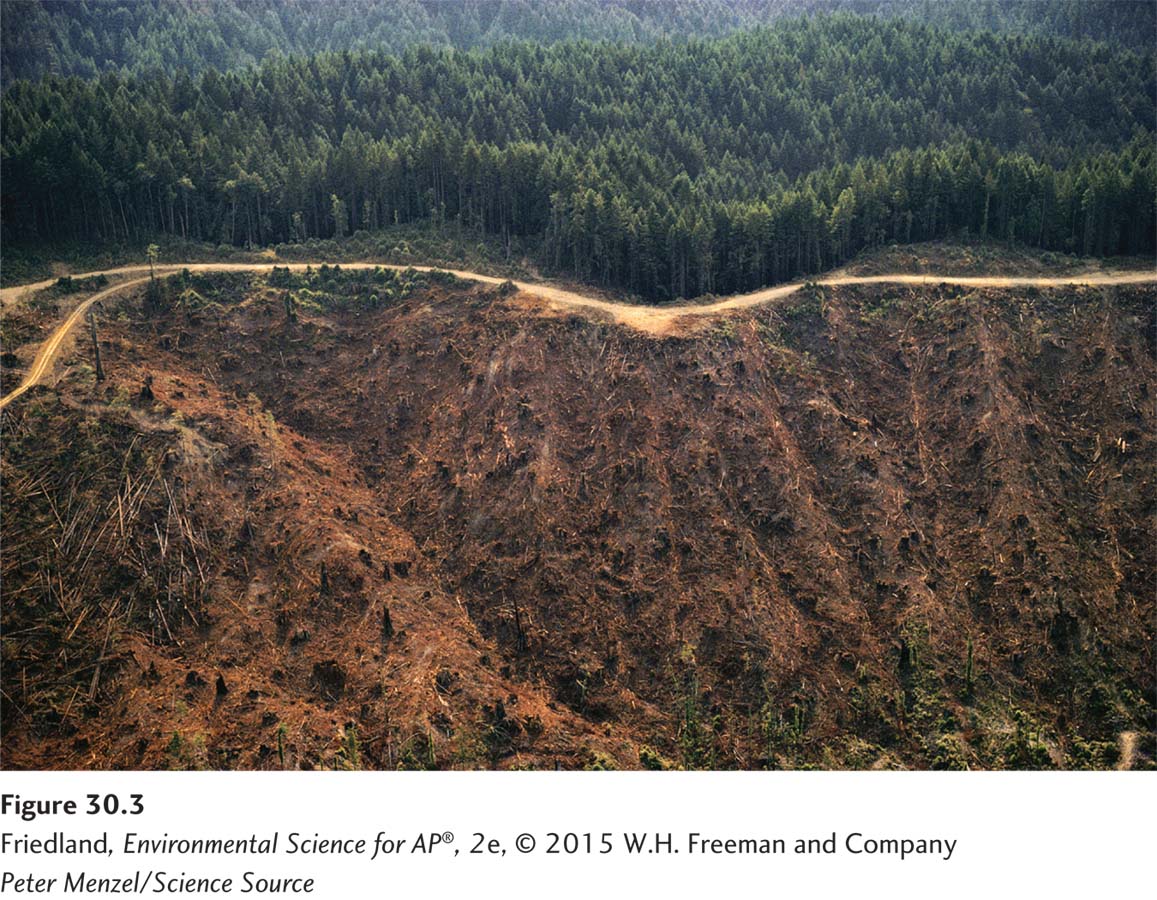

Clear-

The two most common ways in which trees are harvested for timber production are clear-

Clear-

Selective cutting The method of harvesting trees that involves the removal of single trees or a relatively small number of trees from among many in a forest.

Selective cutting (FIGURE 30.2b) removes single trees or a relatively small number of trees from the larger forest. This method creates many small openings in a stand where trees can reseed or young trees can be planted, so the regenerated stand contains trees of different ages. Because seedlings and young trees must grow next to larger, older trees, selective cutting produces optimum growth only among shade-

The environmental impact of selective cutting is less extensive than that of clear-

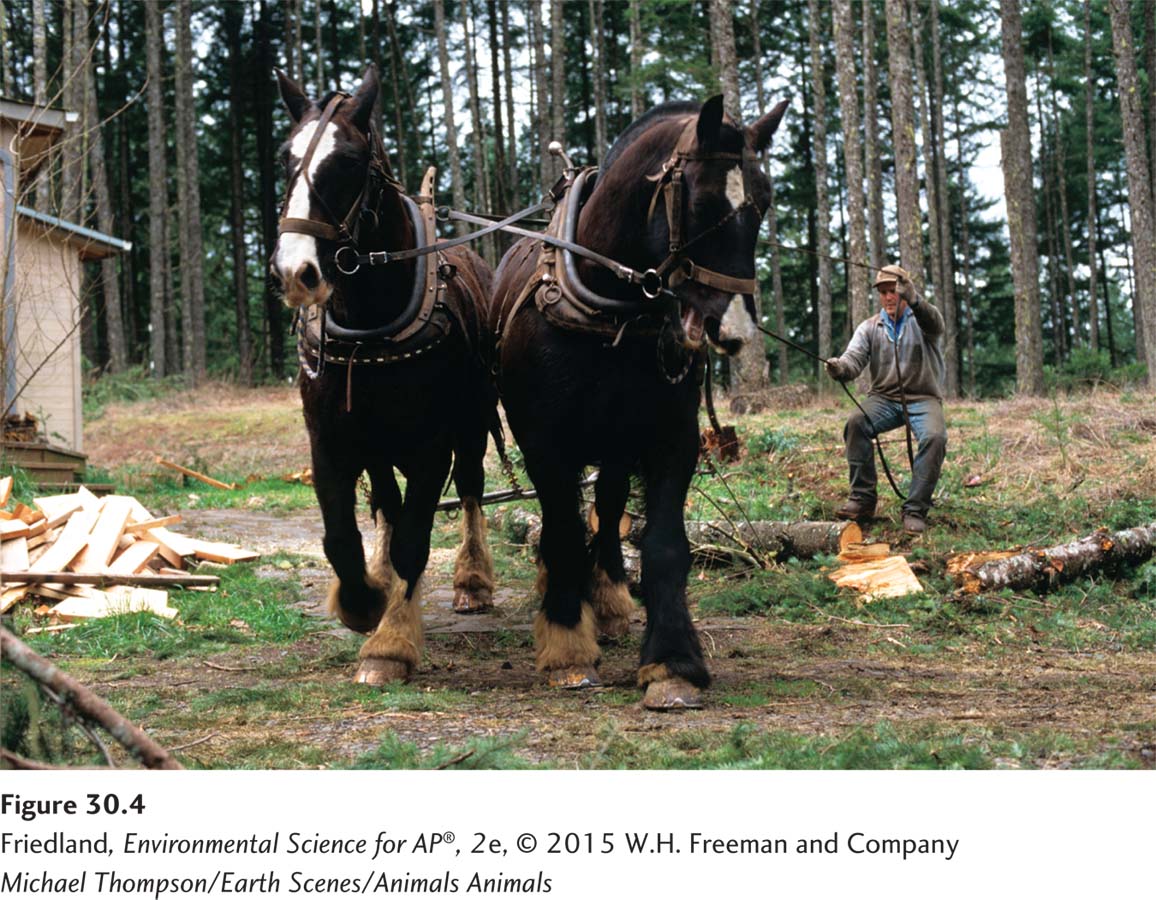

Ecologically sustainable forestry An approach to removing trees from forests in ways that do not unduly affect the viability of other trees.

A third approach to logging—

Logging, Deforestation, and Reforestation

Approximately 30 percent of all commercial timber in the world is produced in the United States and Canada. Compared with South America and Africa, forest losses in these two major timber-

Throughout this chapter we have seen examples of the conflicts over land use created by competing interests and values. Perhaps nowhere is this conflict so clear as in the case of logging. For example, while timber production has always been a part of the mission of the United States Forest Service, maintaining biodiversity is an equally important goal. It would seem that we can’t have both.

All logging disrupts habitat and usually has an effect, either negative or positive, on plant and animal species. One such species is the marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus). This bird spends most of its life along the coastal waters of the Pacific Northwest, but it nests in coastal redwood forests. With the intensive logging of these forests, the marbled murrelet has become endangered. The tree sit described at the beginning of this chapter brought this species, among others, to the public’s attention.

Tree plantation A large area typically planted with a single rapidly growing tree species.

Logging often replaces complex forest ecosystems with tree plantations, which are large areas typically planted with a single rapidly growing tree species. These same-

Since 1982, federal regulations have required the USFS to provide appropriate habitat for plant and animal communities while at the same time meeting multiple-

Fire Management

In many ecosystems, fire is a natural process that is important for nutrient cycling and regeneration. As discussed briefly in Chapter 3, when fires periodically move through an ecosystem, they liberate nutrients tied up in dead biomass. In addition, areas where vegetation is killed by fire provide openings for early-

Prescribed burn A fire deliberately set under controlled conditions in order to reduce the accumulation of dead biomass on a forest floor.

Humans have followed a variety of management policies with respect to fire. For many years, managers of forest ecosystems, including the USFS, worked to suppress fires. This strategy led to the accumulation of large quantities of dead biomass on the forest floor, which built up until a large fire became inevitable. One method for reducing the accumulation of dead biomass is a prescribed burn, in which a fire is deliberately set under controlled conditions. Prescribed burns help reduce the risk of uncontrolled natural fires as well as providing some of the other benefits of fire. More recently, forest managers have allowed certain fires that have occurred naturally to burn. This policy appears to have been accepted in many parts of the United States, as long as human life and property are not threatened.

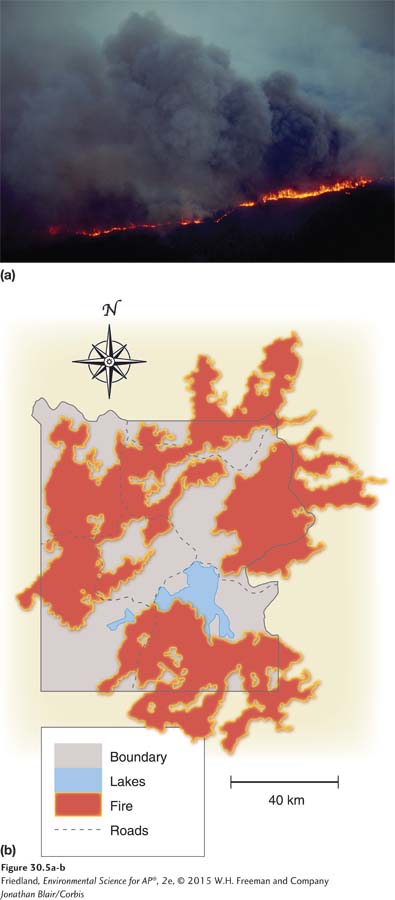

Probably the best-

National Parks

As we have already noted, many national parks were established to preserve scenic views and unusual landforms. Today, national parks are managed for scientific, educational, aesthetic, and recreational use. Since Yellowstone National Park was founded in 1872, 57 additional national parks have been established in the United States. Today the NPS manages a total of 400 national parks and other areas, such as historical parks and national monuments, and the list continues to grow.

The Goals of National Park Management

Management of national parks, like that of national forests, is based on the multiple-

It was not until the 1960s that ecology became a focus of national park management. In 1963, an advisory board on wildlife management presented the Leopold Report to Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall. This report established the guiding principles of national park management that are followed today. It proposed that the primary purpose of NPS should be to maintain the parks in the same biotic condition in which they were first found by European settlers. To this end, the authors believed that NPS should focus its efforts on conservation and on protection of wildlife species and their habitats. The report claimed that human activity had severely affected normal ecological processes in the parks and that active intervention was required to achieve the goal of a return to a more “natural” state.

Today, NPS applies knowledge gained from environmental science to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem function in all national parks. As we saw in the example of the Yellowstone fires, NPS policies continue to be controversial. Each national park adapts U.S. policy to its specific needs. In parks with high levels of endemic biodiversity, for example, management focuses on conserving endemic species. The Channel Islands National Park off the coast of southern California, for instance, is an important breeding ground for many seabirds, including a pelican species rarely found elsewhere in the western United States. Because of this, the Channel Islands National Park is managed primarily to conserve its biodiversity. Other national parks balance biodiversity protection with recreational use.

National Parks and Human Activities

Reducing the impact of human activities both outside and inside park borders is the primary challenge of most national parks throughout the world. Air and water pollution from distant sources can reduce biodiversity, recreational value, and economic opportunities. Ongoing development adjacent to park boundaries can be particularly problematic. In many locations, national parks have become islands of biodiversity amid increasing human development, but even the protected status of the parks cannot defend them completely from invasive species and other problems, such as pollution. These external threats require large-

National parks are also victims of their popularity. Although the park system was established in part to make areas of great beauty accessible to people, human overuse can harm the very environment that attracts visitors. For example, all-

Wildlife Refuges and Wilderness Areas

National wildlife refuge A federal public land managed for the primary purpose of protecting wildlife.

National wildlife refuges are the only federal public lands managed for the primary purpose of protecting wildlife. The Fish and Wildlife Service manages more than 450 national wildlife refuges and 28 waterfowl production areas on 34.4 million hectares (85 million acres) of publicly owned land.

National wilderness area An area set aside with the intent of preserving a large tract of intact ecosystem or a landscape.

National wilderness areas are set aside with the intent of preserving large tracts of intact ecosystems or landscapes. Sometimes only a portion of an ecosystem is included. Wilderness areas are created from other public lands, usually national forests or rangelands, and are managed by the same federal agency that managed them prior to their designation as wilderness areas.

These areas allow only limited human use and are designated as roadless. Although logging, road building, and mining are banned in national wilderness areas, roads that existed before the designation sometimes remain in use, and activities such as mining that were previously permitted on the land are allowed to continue. More than 38.5 million hectares (95 million acres) of federal land, 60 percent of which is in Alaska, are classified as wilderness.

Federal Regulation of Land Use

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) A 1969 U.S. federal act that mandates an environmental assessment of all projects involving federal money or federal permits.

Government regulation can influence the use of private as well as public lands. The 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) mandates an environmental assessment of all projects involving federal money or federal permits. Along with other major laws of the 1960s and 1970s, such as the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act, NEPA creates an environmental regulatory process designed to ensure protection of the nation’s resources.

Environmental impact statement (EIS) A document outlining the scope and purpose of a development project, describing the environmental context, suggesting alternative approaches to the project, and analyzing the environmental impact of each alternative.

Environmental mitigation plan A plan that outlines how a developer will address concerns raised by a project’s impact on the environment.

Endangered Species Act A 1973 U.S. act designed to protect species from extinction.

Before a project can begin, NEPA rules require the project’s developers to file an environmental impact statement. An environmental impact statement (EIS) typically outlines the scope and purpose of the project, describes the environmental context, suggests alternative approaches to the project, and analyzes the environmental impact of each alternative. NEPA does not require that developers proceed in the way that will have the least environmental impact. However, in some situations, NEPA rules may stipulate that building permits or government funds be withheld until the developer submits an environmental mitigation plan stating how it will address the project’s environmental impact. In addition, preparation of the EIS sometimes uncovers the presence of endangered species in the area under consideration. When this occurs, managers must apply the protection measures of the Endangered Species Act, a 1973 law designed to protect species from extinction.

Members of the public are entitled to comment on the environmental assessment and decision makers are required to respond. And, although developers are not obligated to act in accordance with public wishes, in practice public concern often improves the project’s outcome. For this reason, attending informational sessions and providing input is a good way for concerned citizens to learn more about local land use decisions and to help reduce the environmental impact of land development.

Residential land use is expanding

Suburb An area surrounding a metropolitan center, with a comparatively low population density.

Exurb An area similar to a suburb, but unconnected to any central city or densely populated area.

Roughly a century ago, large numbers of people in the United States began to move from rural areas to large cities. The last 50 years have seen an increased movement from those cities to the surrounding areas, which has resulted in the growth of two classes of communities: suburban and exurban. Suburban areas surround metropolitan centers and have low population densities compared with urban areas. Exurban areas are similar to suburban areas, but are not connected to any central city or densely populated area. Since 1950, more than 90 percent of the population growth in metropolitan areas has occurred in suburbs, and two out of three people now live in suburban or exurban communities.

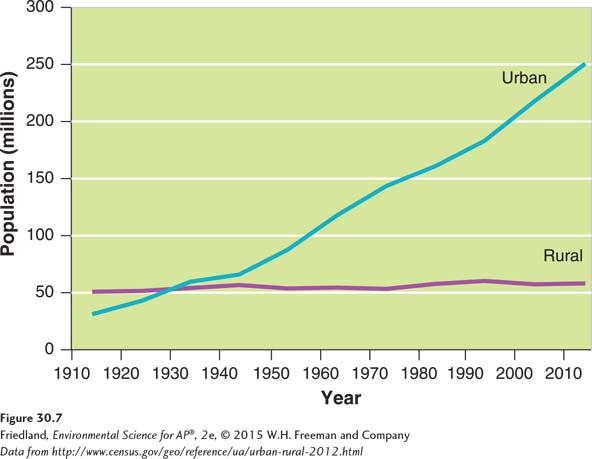

The U.S. census bureau currently categorizes a population as urban if the area contains more than 2,500 people. FIGURE 30.7 shows U.S. urban and rural populations between 1910 and 2012. The rural population in the United States has been roughly the same since 1910, and a century later it makes up less than a fifth of the total U.S. population. Although this population shift has brought with it a new set of environmental problems associated with urban sprawl, attempts to find creative solutions have been increasingly successful.

Causes and Consequences of Urban Sprawl

Urban sprawl Urbanized areas that spread into rural areas, removing clear boundaries between the two.

If you have ever been to a strip mall, you are familiar with the phenomenon known as urban sprawl—urbanized areas that spread into rural areas and remove clear boundaries between the two. The landscape in these areas is characterized by clusters of housing, retail shops, and office parks, which are separated by miles of road. Large feeder roads and parking lots that separate “big box” and other retail stores from the road discourage pedestrian traffic.

Urban sprawl has had a dramatic environmental impact. Dependence on the automobile causes suburban residents to drive more than twice as much as people who live in cities. Between 1950 and 2000, the number of vehicle miles traveled per person in U.S. suburban areas tripled. Because suburban house lots tend to be significantly larger than their urban counterparts, suburban communities also use more than twice as much land per person as urban communities. Urban sprawl tends to occur at the edge of a city, often replacing farmland and increasing the distance between farms and consumers. In its most recent survey, the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated that between 1982 and 2007, U.S. farmland was being converted to residential uses at a rate of 405,000 ha (1 million acres) per year. There are four main causes of urban sprawl in the United States: automobiles and highway construction, living costs, urban blight, and government policies.

Automobiles and Highway Construction

Before automobiles and highway systems existed, transportation into and out of cities was difficult: Horses were slow, roads were bad, and trolley services rarely went far beyond the city limits. In those days, if you wanted to take advantage of the many amenities of city life, such as job opportunities, cultural institutions, shopping, and social activities, you had to live within a few miles of the city center.

The advent of the automobile, and the subsequent development of the interstate highway system in the 1950s and 1960s, changed everything. Today we think nothing of working in the city during the day and commuting home to the suburbs at night. And if you live in the suburbs but want to get into the city on a Saturday night for dinner, a concert, or a movie, that’s no problem either. With rapid, comfortable transportation between urban and suburban areas, it became possible to work or play in the city and then return to a large home in a quiet neighborhood. For the first time in history, people could enjoy the best of both worlds.

Living Costs

Land in the suburbs, because it is readily available, is relatively inexpensive when compared with land in the city. For the cost of a tiny one-

Although single-

Urban Blight

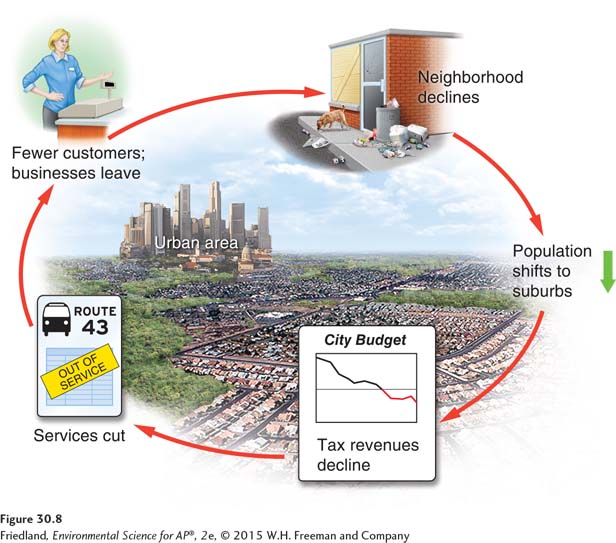

We have seen that urban sprawl encourages population shifts to the suburbs. As people leave the city, city revenue from sources such as property, sales, and service taxes begins to shrink. However, the cost of maintaining urban services, including public transportation, police and fire protection, and social services, does not decrease. Faced with declining tax receipts, cities are forced to reduce services, raise tax rates, or both. As services decline, crime rates may increase, either because police resources are stretched thin or because conditions for lower-

Urban blight The degradation of the built and social environments of the city that often accompanies and accelerates migration to the suburbs.

In addition, as the population shifts to the suburbs, jobs and services follow. Suburbanization has spawned suburban office parks, which have led to an increase in suburb-

Historically, urban blight has contributed to racial segregation. In the 1950s and 1960s, when migration to the suburbs began in earnest, those leaving the cities for the suburbs were predominantly middle-

Government Policies

Urban sprawl has also been enhanced by federal and local laws and policies, including the Highway Trust Fund, zoning laws, and subsidized mortgages.

Highway Trust Fund A U.S. federal fund that pays for the construction and maintenance of roads and highways.

Induced demand The phenomenon in which an increase in the supply of a good causes demand to grow.

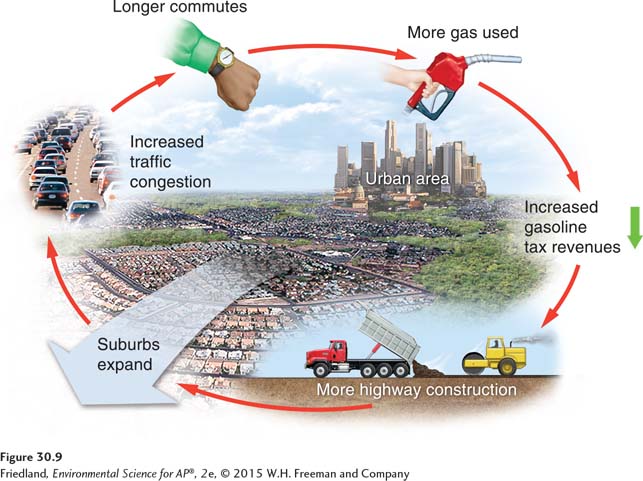

The Highway Trust Fund, begun by the Highway Revenue Act of 1956 and funded by a federal gasoline tax, pays for the construction and maintenance of roads and highways. We have already seen that highways allow people to live farther from where they work. FIGURE 30.9 shows the resulting positive feedback loop. More highways mean more driving and more gasoline purchases, which lead to more gasoline tax receipts that pay for more roads, and so on. As people move farther away from their jobs, traffic congestion increases, and roads are expanded. But the new, even larger roads encourage even more people to live farther away from work. This cycle exemplifies a phenomenon known as induced demand, in which an increase in the supply of a good causes demand to grow.

Zoning A planning tool used to separate industry and business from residential neighborhoods.

Governments may use zoning to address issues of traffic congestion, urban sprawl, and urban blight. Zoning is a planning tool developed in the 1920s and used to separate industry and business from residential neighborhoods, thereby creating quieter, safer communities. Governments that use zoning can classify land areas into “zones” in which certain land uses are restricted. For instance, zoning ordinances might prohibit developers from building a factory or a strip mall in a residential area or a multi-

Multi-

Zoning often regulates much more than land use. The number of parking spaces a building must have, how far from the street a building must be placed, or even the size and location of a home’s driveway are among the development features that zoning may stipulate. Zoning laws have been helpful in addressing issues of safety and sometimes in minimizing environmental damage caused by new construction. One negative aspect of zoning, however, is that it generally prohibits suburban neighborhoods from developing a traditional “Main Street” with shops, apartments, houses, and businesses clustered together. Many communities are now attempting to incorporate multi-

The federal government has also played a large part in encouraging the growth of suburbs through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Congress established the FHA during the Great Depression of the 1930s, in part to jump-

Smart Growth

Smart growth A set of principles for community planning that focuses on strategies to encourage the development of sustainable, healthy communities.

People are beginning to recognize and address the problems of urban sprawl. One approach, smart growth, focuses on strategies that encourage the development of sustainable, healthy communities. The Environmental Protection Agency lists 10 basic principles of smart growth:

Create mixed land uses. Smart growth mixes residential, retail, educational, recreational, and business land uses. Mixed-

use development allows people to walk or bicycle to various destinations and encourages pedestrians to be in a neighborhood at all times of the day, increasing safety and interpersonal interactions. Create a range of housing opportunities and choices. By providing housing for people of all income levels, smart growth counters the concentration of poverty in failing urban neighborhoods. Mixed housing also allows more people to find jobs near where they live, improves schools, and generates strong support for neighborhood transit stops, commercial centers, and other services.

Create walkable neighborhoods. Walkable neighborhoods are created by mixing land uses, reducing the speed of traffic, encouraging businesses to build stores directly up to the sidewalk, and placing parking lots behind buildings. In neighborhoods that encourage walking, people use their cars less, reducing fossil fuel use and traffic congestion and providing health benefits. Communities with more pedestrians tend to see more interaction among neighbors because people stop to talk with each other. This, in turn, creates opportunities for civic engagement. When people interact, the environment usually benefits.

Page 348Stakeholder A person or organization with an interest in a particular place or issue.

Encourage community and stakeholder collaboration in development decisions. There is no single “right” way to build a neighborhood; residents and stakeholders—people with an interest in a particular place or issue—

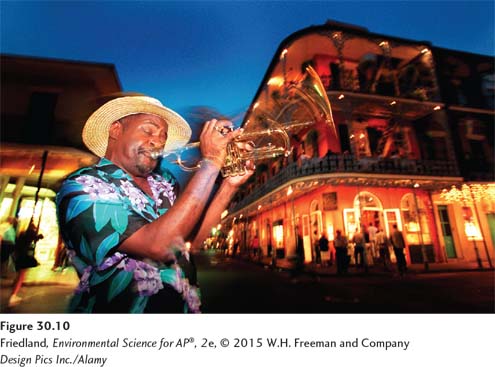

need to work together to determine how their neighborhoods will appear and be structured.  FIGURE 30.10FIGURE 30.10 The French Quarter of New Orleans. One principle of smart growth is to foster communities with a strong sense of place. The French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, is known for its architecture, food, and, especially, music.(Design Pics Inc./Alamy)

FIGURE 30.10FIGURE 30.10 The French Quarter of New Orleans. One principle of smart growth is to foster communities with a strong sense of place. The French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, is known for its architecture, food, and, especially, music.(Design Pics Inc./Alamy)Take advantage of compact building design. Smart growth incorporates multistory buildings and parking garages—

as opposed to sprawling parking lots— to reduce a neighborhood’s environmental footprint and protect more open space. Ideally, shops, cafés, and small businesses should be easily accessible to pedestrian traffic on the ground floor near sidewalks, with two or three stories of apartments and offices above. Sense of place The feeling that an area has a distinct and meaningful character.

Foster distinctive, attractive communities with a strong sense of place. A sense of place is the feeling that an area has a distinct and meaningful character. Many cities have such unique neighborhoods. For example, the French Quarter of New Orleans (FIGURE 30.10) has a sense of place that adds to the quality of life for people living there. Smart growth attempts to foster this sense of place through development that fits into the neighborhood.

FIGURE 30.11FIGURE 30.11 Light rail system. Light rail is one option in transit-

FIGURE 30.11FIGURE 30.11 Light rail system. Light rail is one option in transit-oriented development (TOD), which strives to develop communities with a denser mix of retail and residential components around a convenient public transportation system. (AP Photo/Steve C. Wilson)Preserve open space, farmland, natural beauty, and critical environmental areas. Working farmland is a source of fresh local produce and other goods. Open space provides opportunities for recreation and enjoyment. Land protected from development through restricted growth also provides habitats for a variety of species.

Transit-

oriented development (TOD) Development that attempts to focus dense residential and retail development around stops for public transportation, a component of smart growth.Provide a variety of transportation choices. Transit-

oriented development (TOD) attempts to focus dense residential and retail development around public transportation stops, giving people convenient alternatives to driving. Bicycle racks and safe roads, pleasant sidewalks for walking, frequent bus service, and light rail service can all aid in this goal (FIGURE 30.11). Car-sharing networks such as Zipcar can provide easy access to a fleet of rental automobiles. This increasingly popular service reduces the need for private car ownership where public transportation is not available. Page 349Infill Development that fills in vacant lots within existing communities.

Urban growth boundary A restriction on development outside a designated area.

Strengthen and direct development toward existing communities. Development strategies can help to reinvigorate urban neighborhoods that are caught in a vicious cycle of depopulation and blight and can protect rural lands from sprawl. Development that fills in vacant lots within existing communities, rather than expanding into new land outside the city, is known as infill. Some cities, such as Portland, Oregon, have had success with urban growth boundaries, which place restrictions on development outside a designated area.

Make development decisions predictable, fair, and cost-

effective. Suburban developments throughout the country often look the same because standardized designs allow developers to move rapidly through the permitting process. A streamlined approval process that encourages smart growth could increase the number of individualized plans rather than promoting cookie-cutter development.

Of course, no individual new development or neighborhood plan is likely to incorporate all of these ideals, but as a guide to thinking about how to build communities, the smart growth concept has been quite successful.

Smart growth can have important environmental benefits. For example, compact development reduces the amount of impervious surface, reducing runoff and flooding downstream. A 2000 study found that smart growth in New Jersey would reduce water pollution by 40 percent compared with the more common, dispersed growth pattern. By mixing uses and providing transportation options, smart growth also reduces fossil fuel consumption. A 2005 study in Seattle found that residents of neighborhoods incorporating just a few of the techniques to make non-