module 31 Human Nutritional Needs

In both the developed and developing worlds, human nutritional requirements are being met to varying degrees. Since agriculture first started to be practiced more than 10,000 years ago, farmers have been able to increase agricultural output through improved technology and more efficient use of resources. While these improvements have been beneficial to the overall output of food resources, they have not necessarily been beneficial to human well-

Learning Objectives

After reading this module, you should be able to

describe human nutritional requirements.

explain why nutritional requirements are not being met in various parts of the world.

Human nutritional requirements are not always satisfied

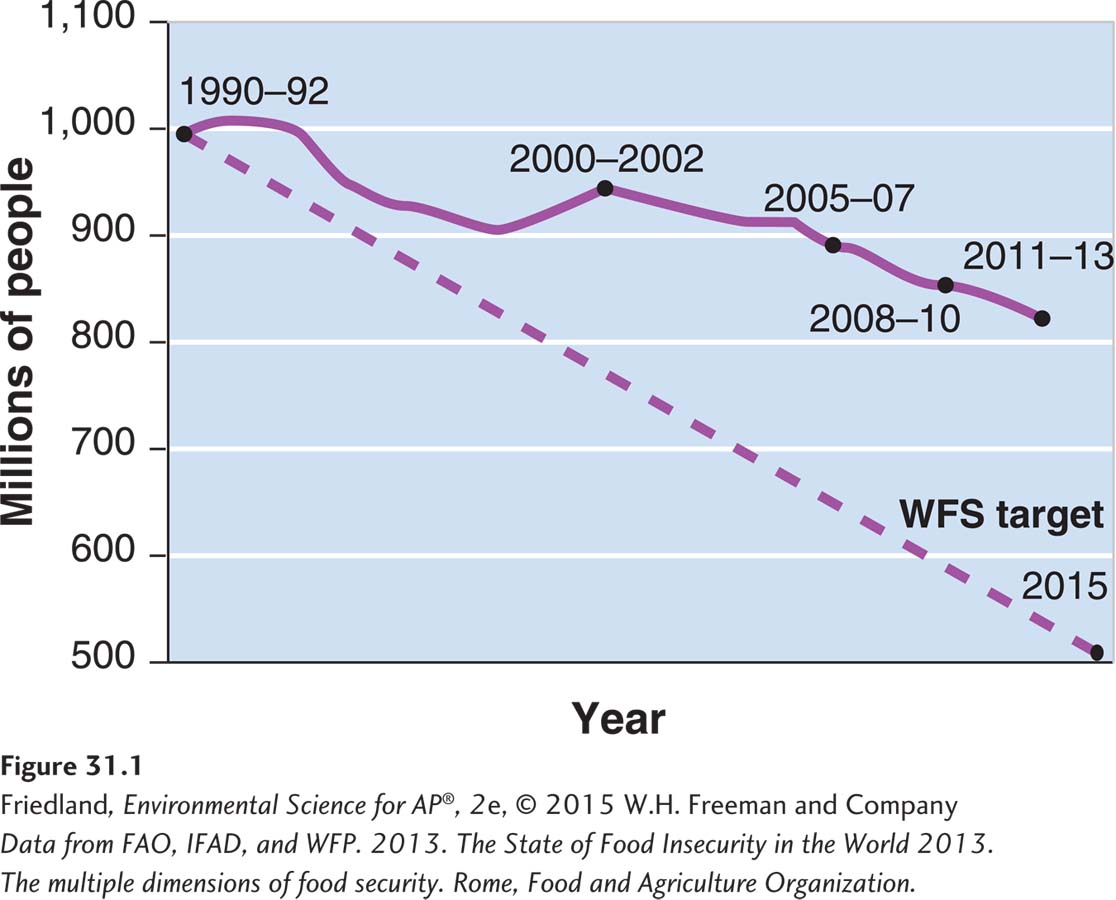

Advancements in agricultural methods are believed to have greatly improved the human diet over the last 10,000 years. In particular, tremendous gains in agricultural productivity and food distribution were made in the twentieth century. But despite these advances, many people throughout the world do not receive adequate nutrition. As FIGURE 31.1 shows, over 800 million people worldwide lack access to adequate amounts of food. Although that number has been declining for decades, it is still way above target numbers set by various world agencies. Currently, as many as 24,000 people starve to death each day—

Undernutrition The condition in which not enough calories are ingested to maintain health.

Chronic hunger, or undernutrition, means not consuming enough calories to be healthy. Food calories are converted into usable energy by the human body. Not receiving enough food calories leads to an energy deficit. An average person needs approximately 2,200 kilocalories per day, though this amount varies with gender, age, and weight. A long-

Malnourished Having a diet that lacks the correct balance of proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals.

In addition, a person lacking sufficient food calories is probably lacking sufficient protein and other nutrients. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 3 billion people—

Food security A condition in which people have access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs for an active and healthy life.

Food insecurity A condition in which people do not have adequate access to food.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines food security as the condition in which people have access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs for an active and healthy life. Access refers to the economic, social, and physical availability of food. Food insecurity refers to the condition in which people do not have adequate access to food.

Famine The condition in which food insecurity is so extreme that large numbers of deaths occur in a given area over a relatively short period.

Famine is a condition in which food insecurity is so extreme that large numbers of deaths occur in a given area over a relatively short period. Actual definitions of famine vary widely depending on the agency using the term. One relief agency defines a famine as an event in which there are more than 5 deaths per day per 10,000 people due to lack of food. According to this definition, there is an annual mortality rate of 18 percent during a famine. Famines are often the result of crop failures, sometimes due to drought, although famines can have social and political causes.

Anemia A deficiency of iron.

Even when people have access to sufficient food, a deficit in just one essential vitamin or mineral can have drastic consequences. The WHO estimates that more than 250,000 children per year become blind due to a vitamin A deficiency. Iron deficiency, known as anemia, is the most widespread nutritional deficiency in the world. The WHO estimates that there are 3 billion anemic people in the world—

Overnutrition Ingestion of too many calories and a lack of balance of foods and nutrients.

In the last few decades, one other form of malnutrition has been increasing. Overnutrition, the ingestion of too many calories combined with a lack of proper balance in foods and nutrients, causes a person to become both overweight and malnourished. The WHO estimates that there are over 1 billion people in the world who are overweight, and that roughly 300 million of those people are obese, meaning they are more than 20 percent above their ideal weight. Overnutrition is a type of malnutrition that puts people at risk for a variety of diseases, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. While overnutrition is common in developed countries such as the United States, it can also coexist with malnutrition in developing countries. Childhood obesity is a related condition that has started to occur in greater numbers. Overnutrition is often a function of the availability and affordability of certain kinds of foods. For example, overnutrition in the United States has been attributed in part to the easy availability and low cost of processed foods containing ingredients such as high-

Meat Livestock or poultry consumed as food.

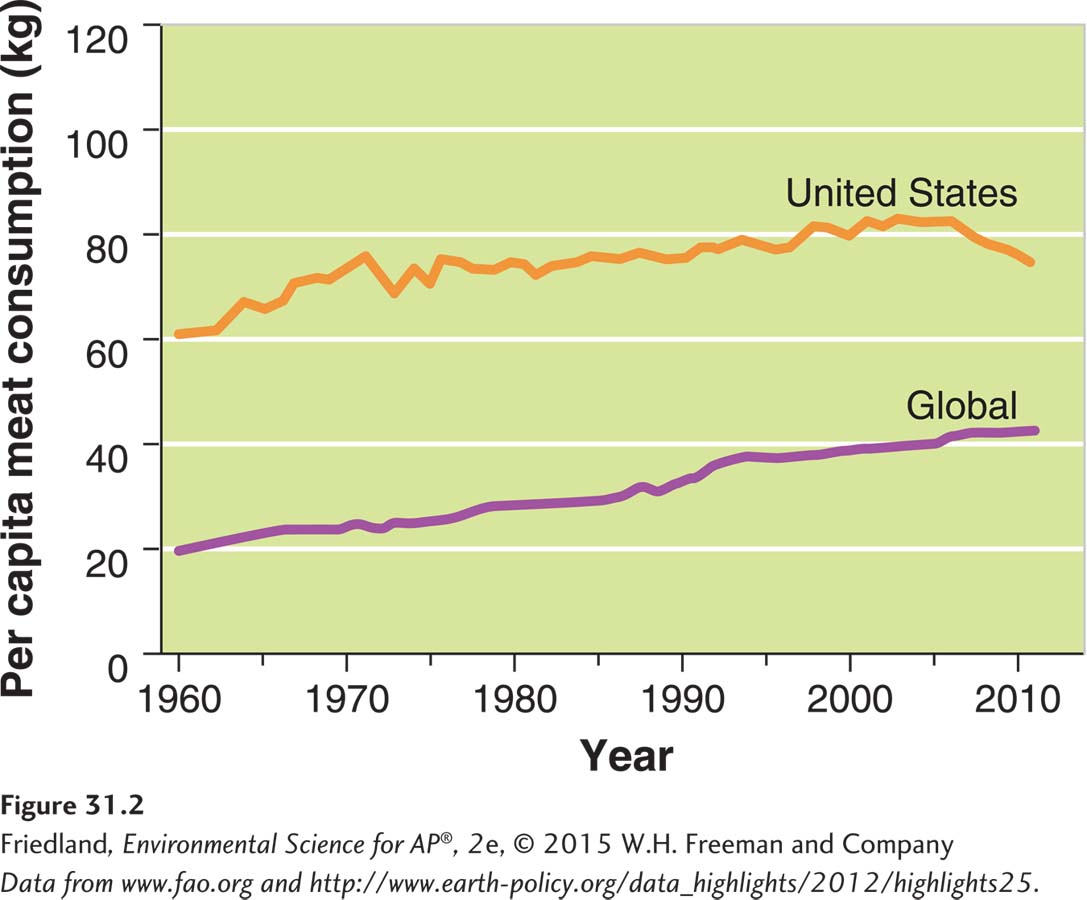

Humans eat a variety of foods, but grains—

Undernutrition and malnutrition occur primarily because of poverty

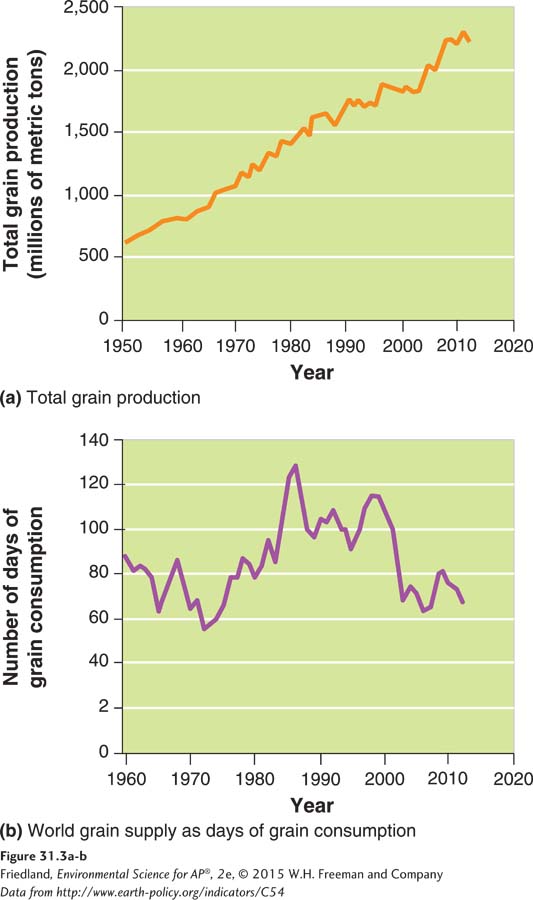

Currently, the world’s farmers grow enough grain to feed at least 8 billion people, which would appear to be more than enough for the world’s population of 7.1 billion. And grain is only a little more than one-

The primary reason for undernutrition and malnutrition is poverty: the lack of resources that allows a person to have access to food. According to many food experts, starvation on a global scale is the result of unequal distribution of food rather than absolute scarcity of food. In other words, the food exists but not everyone has access to it. This may mean that people cannot afford to buy the food they need, which is a problem that cannot be solved just by producing more grain.

In addition, political and economic factors play an important role. For example, refugee populations that have fled their homes due to war or natural disasters may not have access to food that they grew and stored but had to leave behind when they became refugees. Many times in modern history the lack of an adequate food supply has led to political unrest because people without the means to feed themselves or their families may resort to crime or violence in an attempt to improve their situation. More recently, a rise in food prices in 2008 led to food riots in Haiti, Egypt, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Yemen, and elsewhere. Poor governance and political unrest can lead to inadequate food supplies as well, so they can be both causes and effects of undernutrition and malnutrition.

Food researchers have also observed that large amounts of agricultural resources are diverted to feed livestock and poultry rather than people. In fact, roughly 40 percent of the grain grown in the world is used to feed livestock. In the United States, the two largest agricultural crops, corn and soybeans, are grown more for animal feed than for people (although more corn is used for ethanol than for either livestock or people). When these foods are fed to livestock, the low efficiency of energy transfer causes much of the energy they contain to be lost from the system, as we saw in Chapter 3. Ultimately, perhaps only 10 to 15 percent of the calories in grain or soybeans fed to cattle are converted into calories in beef. If people ate producers, such as grains and soybeans, rather than primary consumers, such as cattle, it is possible that more food would be available for people.

FIGURE 31.3 shows global grain production since 1950. A large number of factors influence grain production, including the amount of land under cultivation, global weather and precipitation patterns, world prices for grain, and the productivity of the land on which grain is being grown. As FIGURE 31.3a shows, grain production has been steadily increasing, though there have been some years within the last decade with no increase in production. Number of days of grain consumption in reserve, as FIGURE 31.3b shows, has varied considerably in the last three decades but is roughly similar to numbers of days of reserve available in 1980. There is not a perfectly clear answer as to why global per capita grain production has not continued to increase. Some environmental scientists suggest that we have finally reached the limit of our ability to supply the human population with food while others blame some of the political and social factors that we mentioned above.

In Chapter 7 we learned that the human population is expected to be between 8 and 10 billion by 2050. To feed everyone in the future, we will have to put more land into agricultural production, improve crop yields, reduce the consumption of meat, harvest more from the world’s fisheries, or use some combination of these strategies.

Experts disagree on whether it is feasible to greatly expand food production. Optimists point to new techniques for crop development as well as unused land in tropical rainforests and grasslands that could be farmed, while pessimists argue that climate change, decreasing biodiversity, dwindling supplies of water for irrigation, diminishing topsoil, and other factors may make it difficult to produce more crops. To understand what we can do to improve food security in all nations of the world and reduce the environmental consequences of growing food, we will need to examine the farming methods we use today and the trade offs involved in using them.