module 33 Alternatives to Industrial Farming Methods

As problems with industrial agriculture become more apparent, alternatives are gaining more attention. Some of the newer techniques have actually been used in the developing world for thousands of years. In this module, we will examine some of these alternative farming practices. We will also look at the large-

Learning Objectives

After reading this module, you should be able to

describe alternatives to conventional farming methods.

explain alternative techniques used in farming animals and in fishing and aquaculture.

Alternatives to industrial farming methods are gaining more attention

Industrial agriculture has been so successful and widespread that it has come to be known as conventional agriculture. However, in situations in which the cost of labor is not the most important consideration, traditional farming techniques may also be economically successful. Small-

Shifting Agriculture and Nomadic Grazing

Shifting agriculture An agricultural method in which land is cleared and used for a few years until the soil is depleted of nutrients.

In locations with a moderately warm climate and relatively nutrient-

If a plot is used for a few years and then abandoned for a number of decades, over time the soil may recover its organic content and nutrient supplies and the vegetation may have a chance to regrow. However, population pressures may cause the land to be used too frequently to allow for its full recovery. In that case, soil productivity can decrease rapidly, leaving the land suitable only for animal grazing. In addition, the burning process oxidizes carbon, meaning that it converts it into the oxide compounds carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2). In this way, carbon from the vegetation and the soil is released into the atmosphere and ultimately contributes to higher atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

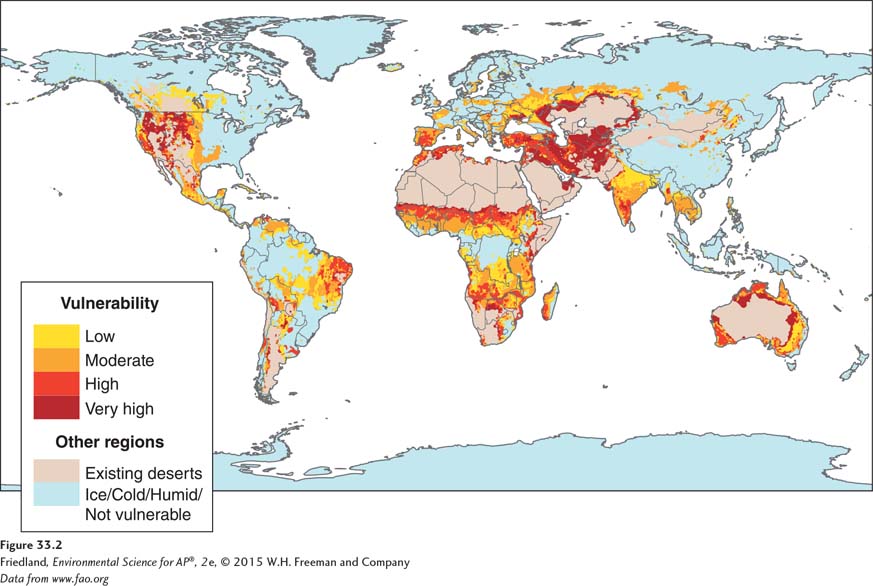

Desertification The transformation of arable, productive land to desert or unproductive land due to climate change or destructive land use.

In semiarid environments, dry, nutrient-

Nomadic grazing The feeding of herds of animals by moving them to seasonally productive feeding grounds, often over long distances.

The only sustainable way for people to use soil types with very low productivity is nomadic grazing, in which they move herds of animals, often over long distances, to seasonally productive feeding grounds. If grazing animals move from region to region without lingering in any one place for too long, the vegetation can usually regenerate.

Shifting agriculture and nomadic grazing worked well under the conditions in which they were first developed—

Sustainable Agriculture

Sustainable agriculture Agriculture that fulfills the need for food and fiber while enhancing the quality of the soil, minimizing the use of nonrenewable resources, and allowing economic viability for the farmer.

Is it possible to produce enough food to feed the world’s population without destroying the land, polluting the environment, or reducing biodiversity? Sustainable agriculture fulfills the need for food and fiber while enhancing the quality of the soil, minimizing the use of nonrenewable resources, and allowing economic viability for the farmer. It emphasizes the ability to continue agriculture on a given piece of land indefinitely through conservation and soil improvement. Sustainable agriculture often requires more labor than industrial agriculture, which makes it more expensive in places where labor costs are high. But practitioners of sustainable agriculture consider the improved long-

Intercropping An agricultural method in which two or more crop species are planted in the same field at the same time to promote a synergistic interaction.

Crop rotation An agricultural technique in which crop species in a field are rotated from season to season.

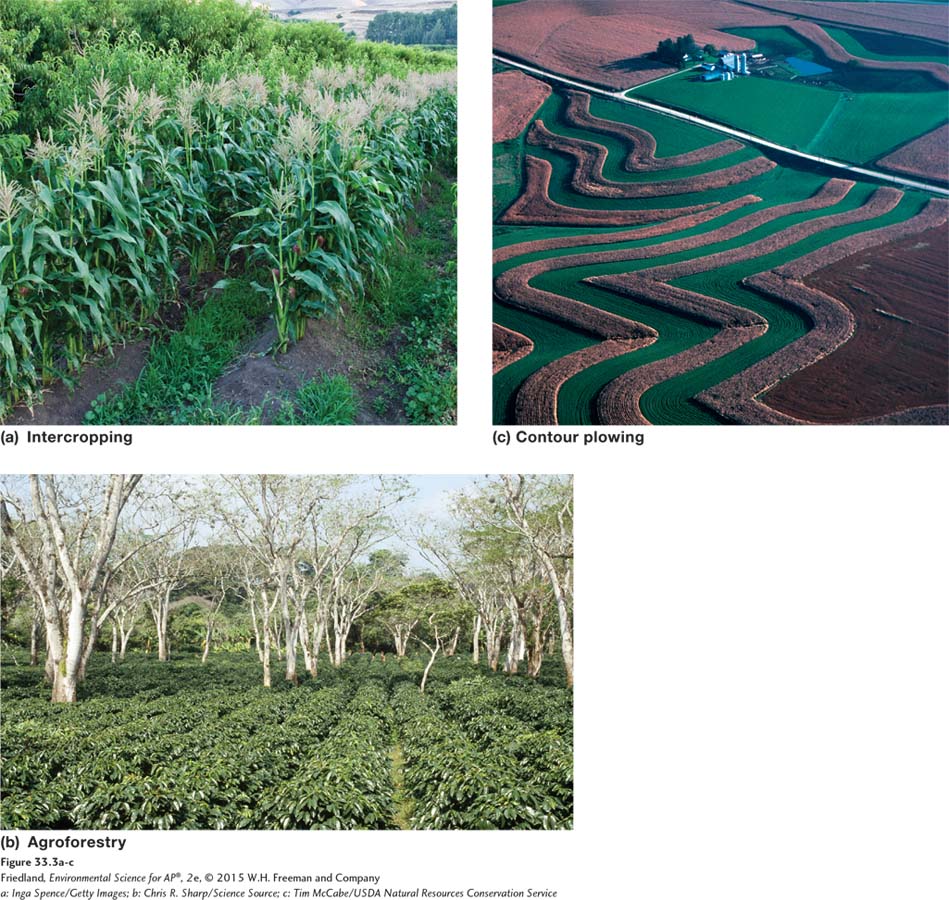

Many of the practices used in sustainable agriculture are traditional farming methods (FIGURE 33.3). Subsistence farmers in India, Kenya, and Thailand typically use animal and plant wastes as fertilizer because they cannot obtain or afford synthetic fertilizers. Such traditional farmers may also practice intercropping (FIGURE 33.3a), in which two or more crop species are planted in the same field at the same time to promote a synergistic interaction between them. For example, corn, which requires a great deal of nitrogen, can be planted along with peas, a nitrogen-

Agroforestry An agricultural technique in which trees and vegetables are intercropped.

Intercropping trees with vegetables—

Contour plowing An agricultural technique in which plowing and harvesting are done parallel to the topographic contours of the land.

Alternative methods of land preparation and use can also help to conserve soil and prevent erosion. For instance, contour plowing—plowing and harvesting parallel to the topographic contours of the land—

No-

Perennial plant A plant that lives for multiple years.

Annual plant A plant that lives only one season.

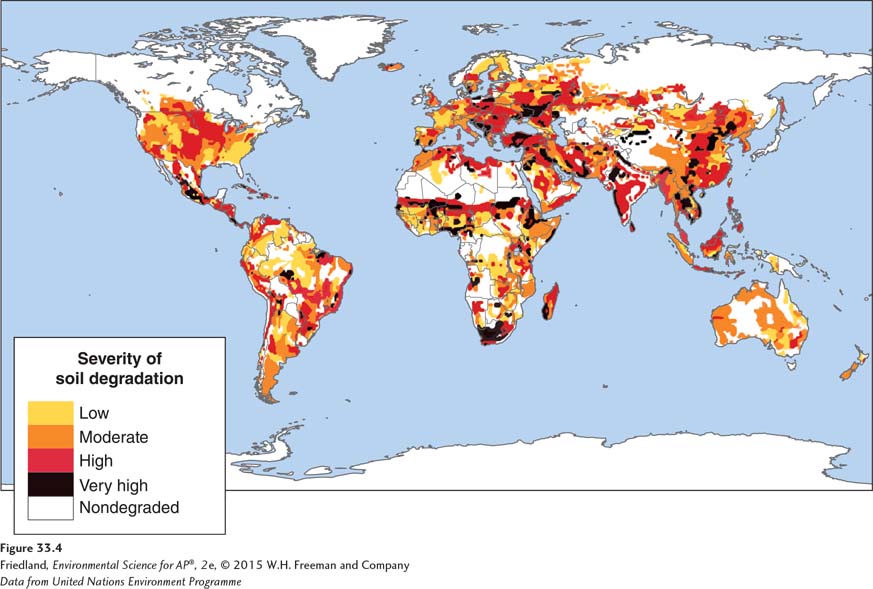

Perennial plants live for multiple years, and there is usually no need to disturb the soil. In contrast, annual plants, such as wheat and corn, live only one season and must be replanted each year. Conventional agriculture of annual plants therefore relies on plowing and tilling, processes that physically turn the soil upside down and push crop residues under the topsoil, thereby killing weeds and insect pupae. Critics argue that plowing and tilling have negative effects on soils. As we learned in Chapter 8, soils may take hundreds or even thousands of years to develop as organic matter accumulates and soil horizons form. Every time soil is plowed or tilled, soil particles that were attached to other soil particles or to plant roots are disturbed and broken apart and become more susceptible to erosion. In addition, repeated plowing increases the exposure of organic matter deep in the soil to oxygen. This exposure leads to oxidation of organic matter, a reduction in the organic matter content of the soil, and an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Tilling, in addition to irrigation and overproduction, has led to severe soil degradation in many parts of the world. The world map in FIGURE 33.4 indicates areas of severe soil degradation.

No-

No-

Integrated Pest Management

Integrated pest management (IPM) An agricultural practice that uses a variety of techniques designed to minimize pesticide inputs.

Another alternative agricultural practice, integrated pest management (IPM), uses a variety of techniques designed to minimize pesticide inputs. These techniques include crop rotation and intercropping, the use of pest-

Crop rotation and the use of pest-

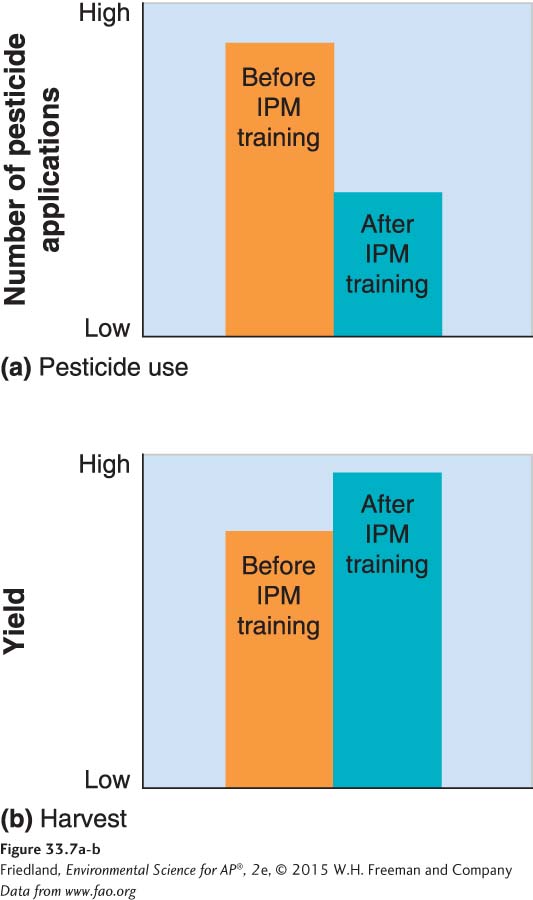

Although IPM practitioners do use pesticides, they limit applications through very careful observation. Farmers regularly inspect their crops for the presence of insect pests and other potential crop hazards to catch them early so they can be treated using natural controls or smaller doses of pesticides than would be needed at later stages of an infestation. These more-

When farmers take time to inspect their fields carefully, as required by IPM methods, they often notice other crop needs, and this additional attention improves overall crop management. The trade off for these benefits is that farmers must be trained in IPM methods and must spend more time inspecting their crops. But once farmers are trained, the extra income and reduced costs associated with IPM often outweigh the extra time they must spend in the field. IPM has been especially successful in many parts of the developing world where the high-

Organic Agriculture

Organic agriculture Production of crops without the use of synthetic pesticides or fertilizers.

Organic agriculture is the production of crops without the use of synthetic pesticides or fertilizers. Organic agriculture follows several basic principles:

Use ecological principles and work with natural systems rather than dominating those systems.

Keep as much organic matter and as many nutrients in the soil and on the farm as possible.

Avoid the use of synthetic fertilizers and synthetic pesticides.

Maintain the soil by increasing soil mass, biological activity, and beneficial chemical properties.

Reduce the adverse environmental effects of agriculture.

In the developed world, organic farming has increased in popularity over the past 3 decades. The U.S. Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA) was enacted as part of the 1990 farm bill to establish uniform national standards for the production and handling of foods labeled organic. “Science Applied 5: How Do We Define Organic Food?” on page 392 discusses organic food labeling in more detail.

For a long time, all organic farms were small, but today this is not necessarily the case. However, because most organic farmers plant diverse crops and encourage beneficial insects, it is common for them to keep their farms relatively small. Organic farmers also must manage the soil carefully because if they lose soil nutrients and see a decline in the health of their crops, they have fewer options than conventional farmers. These practices usually increase labor costs significantly. However, farmers can recoup extra labor costs by selling their harvest at a premium price to consumers who prefer to buy organic food (FIGURE 33.8).

Organic agriculture is not without some adverse environmental consequences. Because organic farmers typically do not use herbicides, they are less likely than conventional farmers to be able to use no-

Alternative techniques for farming animals and fish are becoming more popular

Animals and fish are in general more energy intensive to raise and prepare for eating than vegetable crops, but there are methods for animal and fish production that have a lower environmental impact. This section covers some of those processes.

Not all meat comes from CAFOs. Free-

More Sustainable Fishing

In the interest of creating and supporting sustainable fisheries, many countries around the world have developed fishery management plans, often in cooperation with one another. International cooperation is particularly important because fish migrate across national borders, some marine ecosystems span national borders, and many of the world’s most important fisheries lie in international waters.

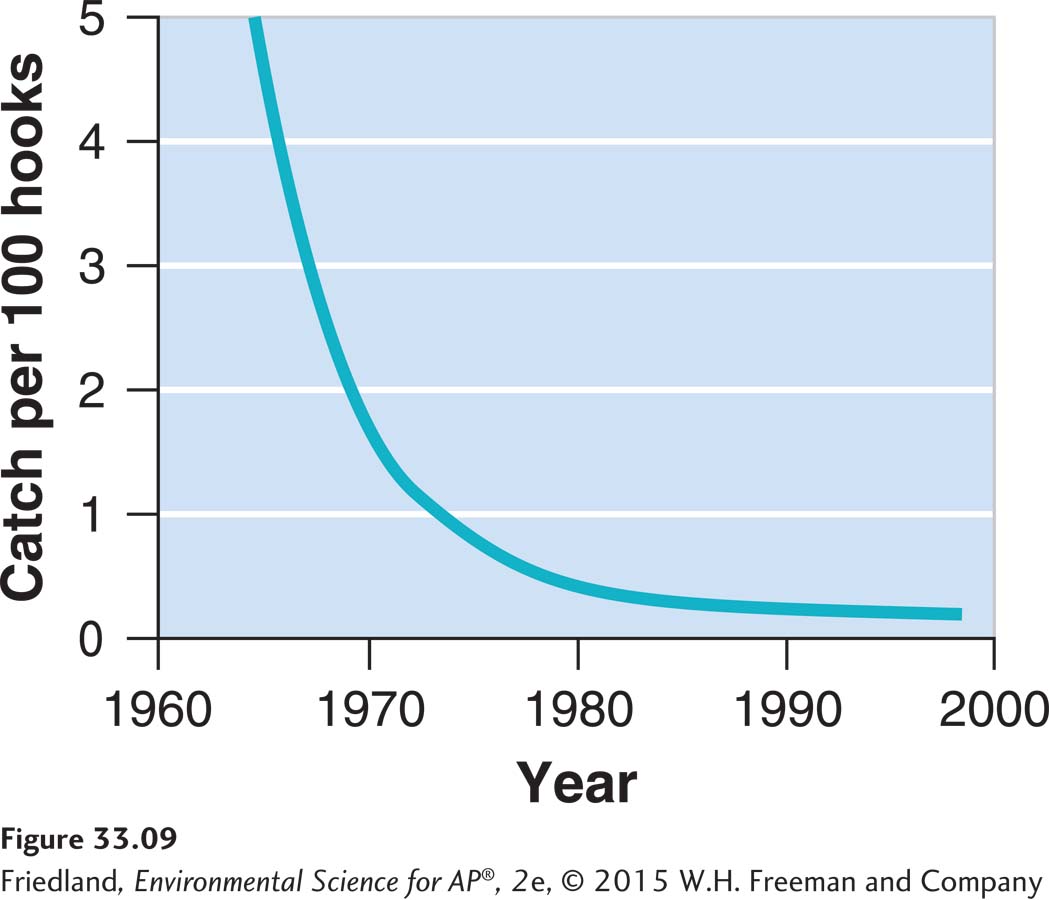

The northwestern Atlantic fisheries, for example, comprise several continental shelf ecosystems that stretch from the northeastern United States to southeastern Canada. Historically, these fisheries were among the most productive in the world. However, overfishing by international fleets of factory ships led to a catastrophic depletion of fish stocks, particularly of cod and pollock, by the early 1990s, as FIGURE 33.9 shows. The fisheries were forced to close because of the depleted stocks, and the Canadian and U.S. governments imposed a moratorium on bottom fishing in the area. The majority of the Atlantic Canadian fisheries are still closed today. Most fisheries in the United States are now open, at least for part of the year.

In response to the fishery collapse, and in order to restore the depleted stocks and manage the ecosystem as a whole, the U.S. Congress passed the Sustainable Fisheries Act in 1996. This act shifted fisheries management from a focus on economic sustainability to an approach that increasingly stressed conservation and the sustainability of species. The act calls for the protection of critical marine habitat, which is important for both commercial fish species and nontarget species. For many commercial species considered to be in danger, such as cod, a sustainable fishery means that no fishing will be permitted until populations recover.

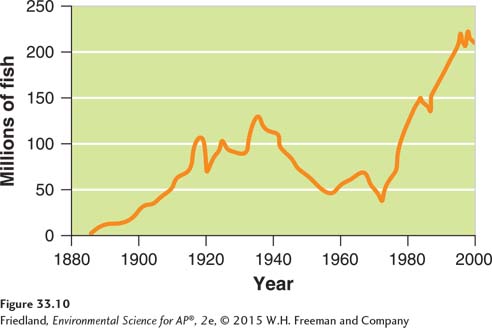

One successful fishery management plan was developed in Alaska, where the commercial salmon fishery declined rapidly between 1940 and 1970. Managers first tried to increase salmon populations by limiting the fishing season, but by 1970, when the season was restricted to less than a week, so many fishers participated that populations continued to drop.

Individual transferable quota (ITQ) A fishery management program in which individual fishers are given a total allowable catch of fish in a season that they can either catch or sell.

In 1973, fishery managers introduced a system of individual transferable quotas (ITQs), a fishery management program in which individual fishers are given a total allowable catch of fish for a season that they can either catch themselves or sell to others. Before the start of each salmon season, fishery managers establish a total allowable catch and distribute or sell quotas to individual fishers or fishing companies, favoring those with long-

In Alaska, ITQs are sold primarily to small family-

Not all fisheries are declining, but it is often difficult for consumers to know which fish are being overharvested and which are not. To help consumers choose more sustainable fish, the Environmental Defense Fund and other organizations have compiled lists of popular food fish, dividing them into three categories, depending on how sustainable their stocks are. “Best” choices include wild Alaskan salmon and farmed rainbow trout. “Worst” choices include shark and Chilean sea bass.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture Farming aquatic organisms such as fish, shellfish, and seaweeds.

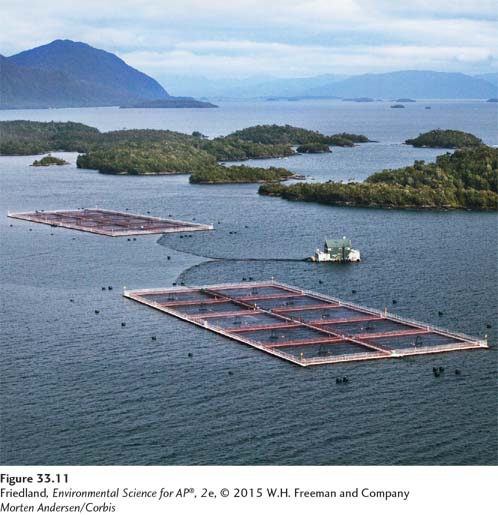

The demand for fish has increased even as wild fish catches have been falling. In response, many scientists, government officials, and entrepreneurs have been developing ways to increase the production of seafood through aquaculture: the farming of aquatic organisms such as fish, shellfish, and seaweeds. Aquaculture involves constructing an aquatic ecosystem by stocking the organisms, feeding them, and protecting them from diseases and predators. It usually requires keeping the organisms in enclosures (FIGURE 33.11), and it may require providing them with food and antibiotics. Almost all of the catfish and trout eaten in the United States, as well as half of the shrimp and salmon, are produced by aquaculture.

Proponents of aquaculture believe it can alleviate some of the human-

Critics of aquaculture, though, point out that it can create many environmental problems. In a typical aquaculture facility, clean water is pumped in at one end of a pond or marine enclosure, and wastewater containing feces, uneaten food, and antibiotics is pumped back into the river or ocean at the other end. The wastewater may also contain bacteria, viruses, and pests that thrive in the high-