module 43 Oil Pollution

In Chapter 12 we noted that the pollution of Earth’s oceans and shorelines from crude oil and other petroleum products is an ongoing problem. Petroleum products are highly toxic to many marine organisms, including birds, mammals, and fish, as well as to algae and microorganisms that form the base of the aquatic food chain. Oil is a persistent substance that can spread below and across the surface of the water for hundreds of kilometers and leave shorelines with a thick, viscous covering that is extremely difficult to remove. In this section, we will examine the many sources of oil pollution and then talk about some of the ways currently used to clean up oil and to reduce its harmful effects.

Learning Objectives

After reading this module you should be able to

identify the major sources of oil pollution.

explain some of the current methods to remediate oil pollution.

There are several sources of oil pollution

There are many different sources of oil pollution in water. Oil and other petroleum products can enter the oceans as spills from oil tankers. One of the best-

In 2009, 20 years after the Exxon Valdez spill, scientists evaluated the state of the contaminated Alaskan ecosystem. They concluded that the harmed populations of many species have rebounded, including bald eagles and salmon. However, several species have not yet rebounded, including killer whales (Orcinus orca) and sea otters (Enhydra lutris). Nor has the oil been completely removed from the environment. Pits dug into the shoreline suggest that approximately 55,000 L (14,500 gallons) of oil remain. It is estimated that this oil will take more than 100 years to break down and the long-

For its part, Exxon has paid $1 billion for the cleanup and $500 million in damages. The company also changed the ship’s name, although the ship has been banned from carrying oil in North America. The Valdez accident sparked new rules for oil tankers in North America. The Exxon Valdez had a single-

Offshore drilling is another source of oil pollution. There are approximately 5,000 offshore oil platforms in North America and another 3,000 worldwide. Drilling platforms often experience leaks. The best estimate for the amount of petroleum leaking into North American waters is 146,000 kg (322,000 pounds) per year. In other parts of the world, antipollution regulations are often less stringent. Estimates of the amount of petroleum leaking into the ocean annually from foreign oil platforms range from 0.3 million to 1.4 million kilograms (0.6 million to 3.1 million pounds).

One of the most famous oil leaks from an offshore platform occurred in 2010 on a BP operation in the Gulf of Mexico. In this case, an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon platform caused a pipe to break on the ocean floor nearly 1.6 km (1 mile) below the surface of the ocean. From the time of the explosion in April until the well was sealed in August 2010, the broken pipe released an estimated 780 million liters (206 million gallons) of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico (see FIGURE 35.4 on page 412). This spill contaminated beaches, wildlife, and the estuaries that serve as habitats for the reproduction of commercially important fish and shellfish. The magnitude of the oil spill was nearly 20 times larger than that of the Exxon Valdez. However, because much of the oil spilled into the ocean, scientists may not be able to assess the full impact of the oil spill for several decades. The accident has the potential to become one of the largest environmental disasters in history.

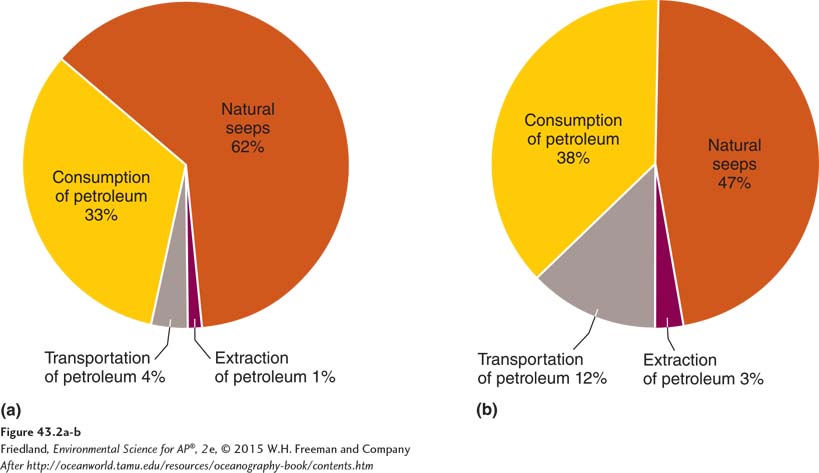

In addition to oil spills, oil pollution in the ocean occurs naturally. In fact, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences recently estimated that natural releases of oil from seeps in the bottom of the ocean account for 60 percent of all oil in the waters surrounding North America and 45 percent of all oil in water worldwide. FIGURE 43.2 shows the proportion of different sources of oil in water for both North American and worldwide marine waters. In the waters controlled by the United States, the ocean seeps more than 270,000 L (70,000 gallons) of oil every day. This means that when we assess the environmental impact of oil in our oceans, we must consider the combination of both natural and anthropogenic releases of oil.

There are ways to remediate oil pollution

Since the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, researchers have been investigating how best to remediate oil spills. Contaminated mammals and waterfowl must be cleaned by hand. Bird feathers that are covered with oil, for example, become heavy and lose their ability to insulate. The best approach to cleaning up the spilled oil, however, is not always clear.

Oil spilled in the ocean can either float on the surface or remain far below in the form of underwater plumes. For oil floating on the surface of the open ocean, a common approach is to contain the oil within an area and then suck it off the surface of the water. Containment occurs by laying out oil containment booms that consist of plastic barriers floating on the surface of the water and extending down into the water for several meters. These plastic walls keep the floating oil from spreading further. Once the oil is contained, boats equipped with giant vacuums suck up as much oil as possible (FIGURE 43.3). In shallow areas and along the coastline, absorbent materials are used to suck up the spilled oil.

A second approach to treating oil floating on the surface is to apply chemicals that help break up and disperse the oil before it hits the shoreline and causes damage to the coastal ecosystems. Although the dispersants can be effective, they can also be toxic to marine life. Current research is examining ways to make chemical dispersants more environmentally friendly.

A third approach to cleaning up oil uses genetically engineered bacteria. Several years ago scientists discovered a naturally occurring bacterium that obtained its energy by consuming oil emerging from natural seeps. These bacteria were typically rare in the ocean, but were very abundant in areas where oil spills or seeps occurred. Scientists are currently trying to determine the genes that confer the bacteria’s ability to consume oil and hope to insert copies of these genes into genetically modified bacteria to consume oil spills even faster.

In contrast to oil floating on the surface of the water, oil in underwater plumes persists as a mixture of water and oil, similar to the mixture of vinegar and oil in a salad dressing. In the case of the BP platform explosion in the Gulf of Mexico, scientists reported observing an oil plume moving approximately 1,000 m (3,000 feet) below the surface of the ocean. The plume was approximately 24 to 32 km (15–

When spilled oil comes to shore, the best solution in not always clear. For example, there is some debate over the best way to treat rocky coastlines after an oil spill. Scientists have been monitoring parts of Prince William Sound that were treated in different ways after the Exxon Valdez spill. Workers cleaned some areas with high-

Other parts of the coastline received no human intervention. Over the years since the spill, the repeated action of waves and tides slowly removed much of the oil. However, the remaining oil existing in crevices of the rocky shoreline continues to have a negative effect on organisms that live among the rocks. Thus, leaving the oil on beaches also poses problems. At present, there is no clear consensus on the best way to respond to oil spills on coastlines.