Page 657

Preserving biodiversity is expensive. A case in point is the money required to set aside terrestrial or aquatic areas for protection. As an example, if the land is privately owned, it must be purchased. Indirect costs can also be high. Not using the land, water, or other natural resources—such as wood materials, metals, and fossil fuels—results in lost income. Finally, the costs of maintaining the protected area can be prohibitive, ranging from monitoring the biodiversity to hiring guards to prevent illegal activities such as poaching. Given the fact that preserving biodiversity is expensive, how can the developing nations of the world, which contain so much biodiversity but have such little wealth, afford it?

In 1984, Thomas Lovejoy from the World Wildlife Fund came up with an idea that would help protect large areas of land but at the same time improve the economic conditions of developing countries. Lovejoy observed that developing nations possessed much biodiversity but were often deep in debt to wealthier, developed countries. Developing countries borrowed large amounts for the purpose of improving economic conditions and political stability. While the developing countries were slowly repaying their loans with interest, some had fallen so far behind on these payments that it seemed unlikely the loans would ever be repaid in full. These debtor countries had little money left over for investment in an improved environment after they had paid their loans to developed countries. Lovejoy considered the possibility that the wealthy countries might be willing to let debtor nations swap their debt in exchange for investing in the conservation of the biodiversity of the debtor nations.

The “debt-for-nature” swap has been used several times in Central and South America. In these swaps, the United States government and prominent environmental organizations provide cash to pay down a portion of a country’s debt to the United States. The debt is then transferred to environmental organizations within that country with the debtor government making payments to the environmental organizations rather than to the United States. This does not mean that the country is out of debt, just that it now sends its loan payments to the environmental organizations for the purpose of protecting the country’s biodiversity. In short, the indebted country switches from sending its money out of the country to investing in its own environmental conservation.

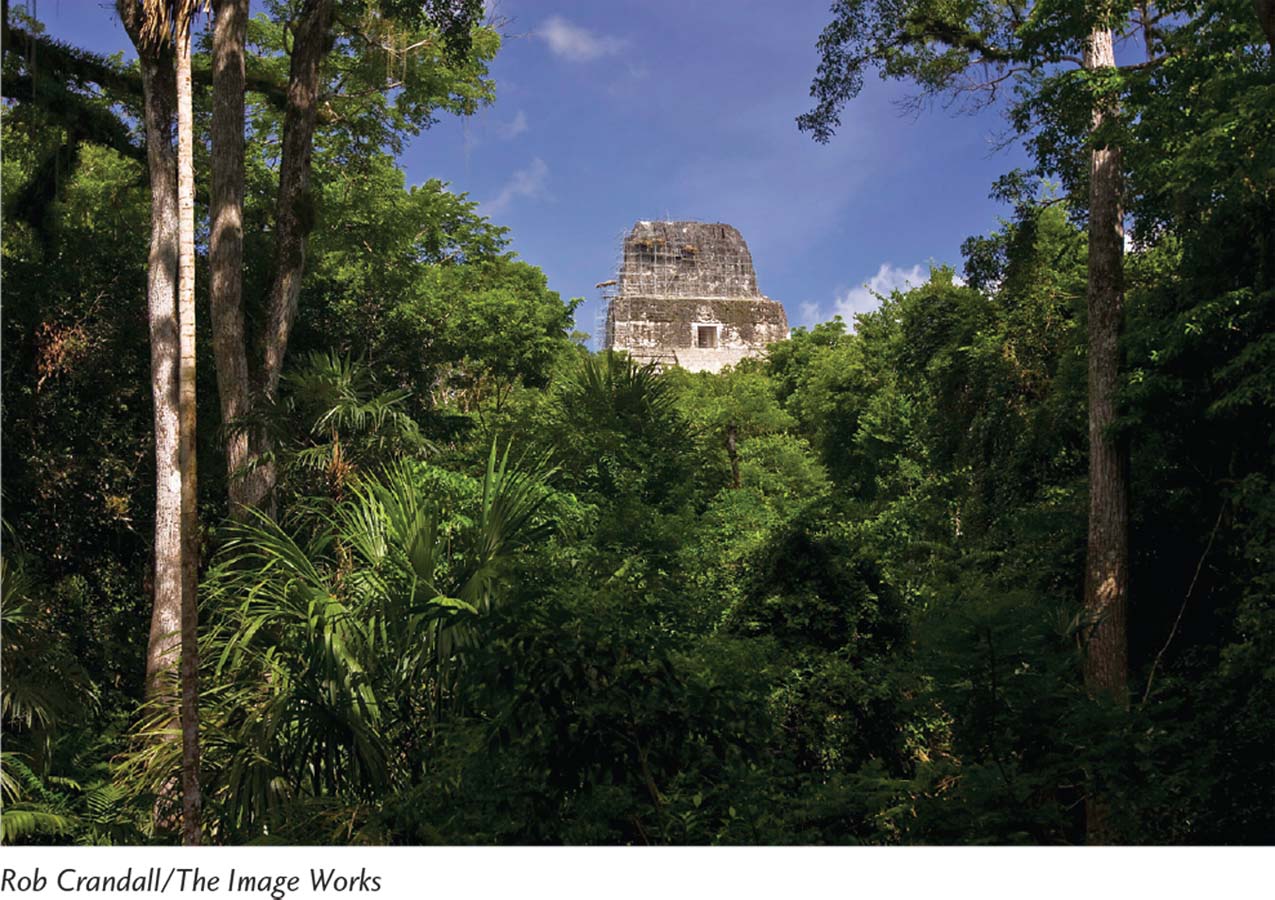

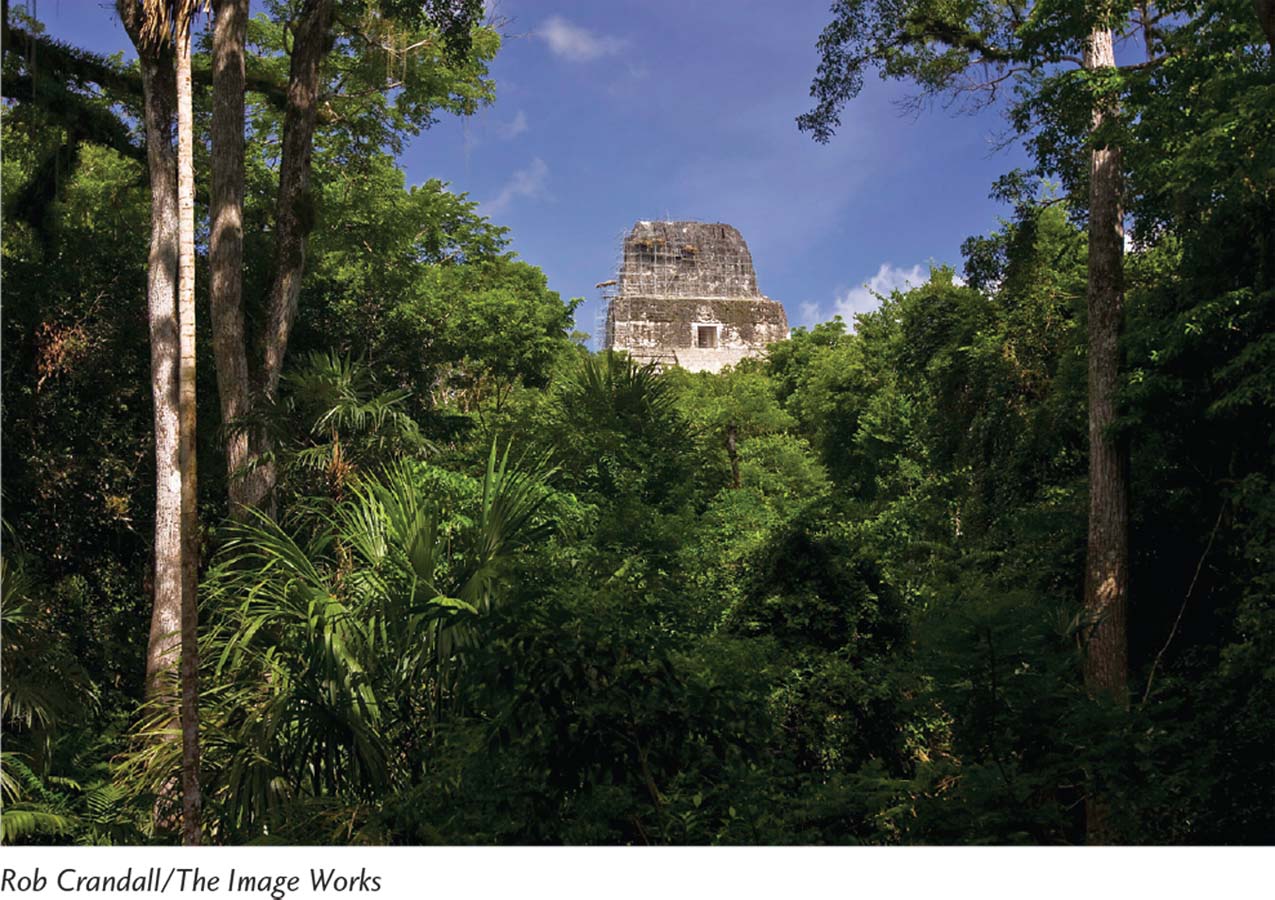

One of the largest debt-for-nature swaps recently happened in the Central American country of Guatemala. The United States government paired with two conservation organizations to provide $17 million to Guatemala. Over a period of 15 years, this amount, with interest, would have grown to more than $24 million, or about 20 percent of Guatemala’s debt to the United States. In exchange, Guatemala agreed to pay $24 million over 15 years to improve conservation efforts in four areas of the country, including the purchase of land, the prevention of illegal logging, and future grants to conservation organizations helping to document and preserve the local biodiversity. The four areas include two ecosystems—mangrove forests and tropical forests. Each forms a core area within a biosphere reserve that contains a large number of rare and endangered species including the jaguar (Panthera onca). More than twice the size of Yellowstone National Park in the United States, this reserve offers important protection to biodiversity while also preserving historic Mayan temples that are part of Guatemala’s cultural heritage and allowing sustainable use of some of the forest by local people.

Swapping debt for nature in Guatemala. The Maya Biosphere Reserve is one of four areas of Guatemala that will be better protected under an agreement between the governments of the United States and Guatemala as well as several conservation organizations.

(Rob Crandall/The Image Works)

Since the program began in 1998, the United States has used the debt-for-nature swap to protect tropical forests in 15 countries from Central America to the Philippines. To take part in the swap program, the countries are required to have a democratically elected government, a plan for improving their economies, and an agreement to cooperate with the United States on issues related to combating drug trafficking and terrorism. The results of these agreements have been encouraging. In Belize, for example, a debt-for-nature swap allowed 9,300 ha (23,000 acres) to be protected and an additional 109,000 ha (270,000 acres) to be managed for conservation. In Peru, a $10.6 million debt-for-nature swap led to the protection of more than 11 million ha (27 million acres) of tropical forest. Although these arrangements are only currently being applied to tropical forests, there is no inherent reason that this unique, modern-day conservation strategy would not also work in many other developing countries around the world.

Page 658

Critical Thinking Questions

In debt-for-nature swaps, why might the United States require that developing countries receiving such assistance have a plan for improving their economies?

How might the debt-for-nature program promote the goals of the Convention on Biological Diversity?

sustainability

sustainability