201.1 2scienceapplied

How Should We Prioritize the Protection of Species Diversity?

As a result of human activities, we have seen a widespread decline in biodiversity across the globe. Many people agree that we should try to slow or even stop this loss. But how do we do this? While ideally we might want to preserve all biodiversity, in reality preserving biodiversity requires compromises. For example, in order to preserve the biodiversity of an area, we might have to set aside land that would otherwise be used for housing developments, shopping malls, or strip mines. If we cannot preserve all biodiversity, how do we decide which species receive our attention? (FIGURE SA2.1)

Endemic species A species that lives in a very small area of the world and nowhere else.

Biodiversity hotspot An area that contains a high proportion of all the species found on Earth.

In 1988, Oxford University professor Norman Myers noted that much of the world’s biodiversity is concentrated in areas that make up a relatively small fraction of the globe. Part of the reason for this uneven pattern of biodiversity is that so many species are endemic species. Endemic species are species that live in a very small area of the world and nowhere else, often in isolated locations such as the Hawaiian Islands. Because they are home to so many endemic species, these isolated areas end up containing a high proportion of all the species found on Earth. Myers called these areas biodiversity hotspots.

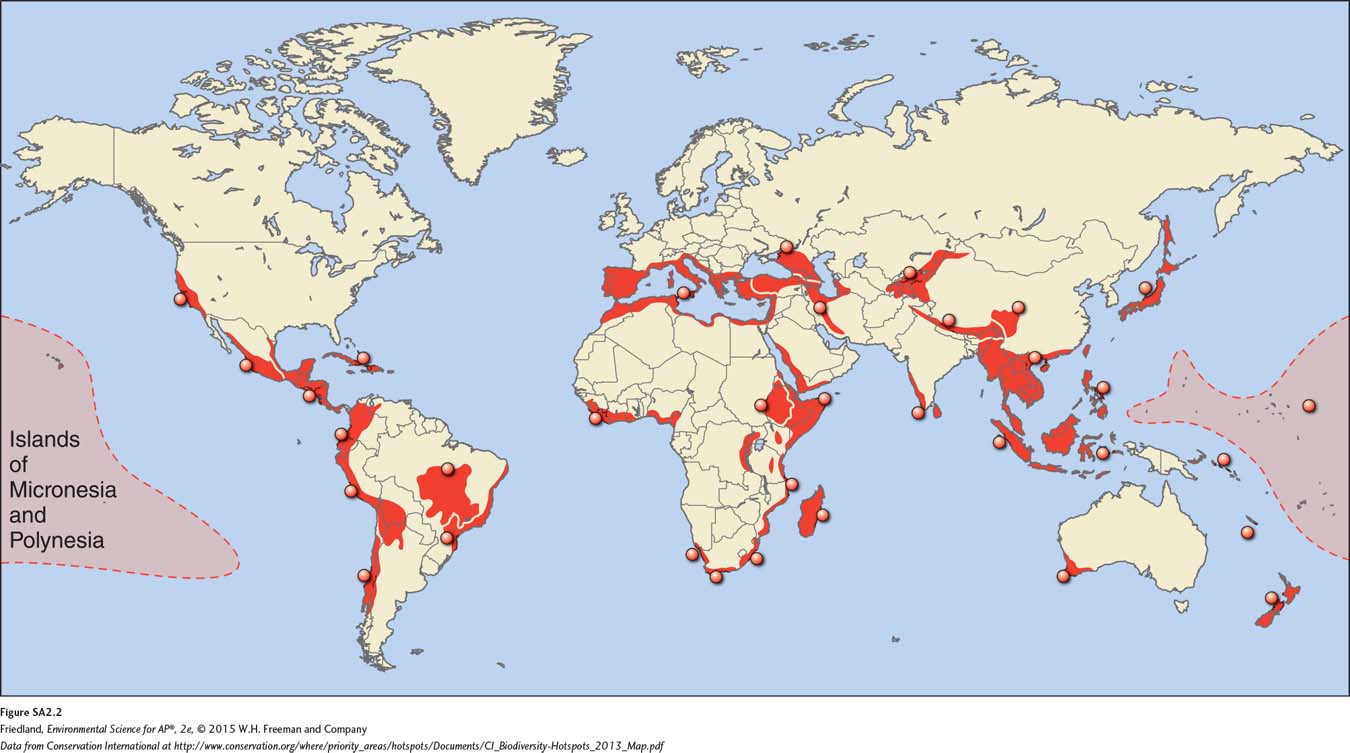

Scientists originally identified 10 biodiversity hotspots, including Madagascar, western Ecuador, and the Philippines. Myers argued that these 10 areas were in need of immediate conservation attention because human activities there could have disproportionately large negative effects on the world’s biodiversity. A year later, the group Conservation International adopted Myers’s concept of biodiversity hotspots to guide its conservation priorities. As of 2013, Conservation International had identified the 34 biodiversity hotspots shown in FIGURE SA2.2. Although these hotspots collectively represent only 2.3 percent of the world’s land area, more than 50 percent of all plant species and 42 percent of all vertebrate species are confined to these areas. As a result of this categorization, major conservation organizations have adjusted their funding priorities and are spending hundreds of millions of dollars to conserve these areas. What does environmental science tell us about the hotspot approach to conserving biodiversity?

What makes a hotspot hot?

Since Norman Myers initiated the idea of biodiversity hotspots, scientists have debated which factors should be considered most important when deciding where to focus conservation efforts. For example, most scientists agree that species richness is an important factor. There are more than 1,300 bird species in the small nation of Ecuador—

Identifying biodiversity hotspots is challenging, however, because scientists have not yet discovered and identified all the species on Earth. Because the distribution of plants is typically much better known than that of animals, the most practical way to identify hotspots has been to locate areas containing high numbers of endemic plant species. It is reasonable to expect that areas with high plant diversity will contain high animal diversity as well.

Conservation International considers two criteria when determining whether an area qualifies as a hotspot. First, the area must contain at least 1,500 endemic plant species. By conserving plant diversity, the hope is that we will simultaneously conserve animal diversity, especially for those groups, such as insects, that are poorly cataloged. Second, the area must have lost more than 70 percent of the vegetation that contains those endemic plant species. In this way, high-

What else can make a hotspot hot?

The number of endemic species in an area is undoubtedly important in identifying biodiversity hotspots, but other scientists have argued that this criterion alone is not enough. They suggest that we also consider the total number of species in an area or the number of species currently threatened with extinction in an area. Would all three approaches identify similar regions of conservation priority? A recent analysis of birds suggests they would not. When scientists identified bird diversity hotspots using each of the three criteria—

Source: Data from C.D. Orme et al., Global hotspots of species richness are not congruent with endemism or threat, Nature 436 (2005): 1016–

| Rank | Total number of species | Number of endemic species | Number of threatened species |

| 1 | Andes | Andes | Andes |

| 2 | Amazon Basin | New Guinea and Bismarck Archipelago | Amazon Basin |

| 3 | Western Great Rift Valley | Panama and Costa Rica Highlands | Guiana Highlands |

| 4 | Eastern Great Rift Valley | Caribbean | Himalayas |

| 5 | Himalayas | Lesser Sunda Islands | Atlantic Coastal Forest, Brazil |

As we can see, some areas of the world that have high species richness do not contain high numbers of endemic species. The Amazon, for example, has a high number of bird species, but not a particularly high number of endemic bird species compared with other more-

In addition to considering species diversity, some scientists have argued that we must also consider the size of the human population in diverse areas. For example, we might expect that natural areas containing more people face a greater probability of being affected by human activities. Furthermore, if we wish to project into the future, we must consider not only the size of the human population today, but also the expected size of the human population several decades from now. Scientists have found that many hotspots for endemic species have human population densities that are well above the world’s average. Whereas the world has an average human population density of 42 people per square kilometer, the average hotspot has a human population of 73 people per square kilometer. Such places may be at a higher risk of degradation from human activities. This risk should be considered when determining priority areas for conservation, and it should motivate us to promote development that does not come at the cost of species diversity.

What are the costs and benefits of conserving biodiversity hotspots?

Conservation efforts that focus on regions with large numbers of species place a clear priority on preserving the largest number of species possible. However, people making these efforts do not explicitly consider the likelihood of succeeding in this goal, nor do they necessarily consider the costs associated with the effort. For example, there may be many ways of helping a species persist in an area, including buying habitat, entering into agreements with landowners not to develop their land, or removing threats such as invasive species. In the case of the California tiger salamander, for example, while eliminating invasive predators may not be feasible, it is possible to protect salamander habitat. In 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to designate more than 20,000 ha (50,000 acres) of habitat as being critical for the salamander’s persistence and in 2012 the agency agreed to develop a plan to help populations of the salamander to recover. Each option will have a different impact on the number of species that will be helped, and each option will have different costs of implementation. Given the limited funds that are available for protecting species, it is certainly worth comparing the expected costs and benefits of different options, both within and among biodiversity hotspots. In this way, we have the potential to maximize the return on our conservation investment.

What about biodiversity coldspots?

The concept of biodiversity hotspots assumes that our primary goal is to protect the maximum number of species. That goal is admirable, but it could come at the cost of many important ecosystems that do not fall within hotspots. Yellowstone National Park, for example, has a relatively low diversity of species, yet it is one of the few places in the United States that contains remnant populations of large mammals, including wolves, grizzly bears, and bison. Does this mean that places such as Yellowstone National Park should receive decreased conservation attention?

Biodiversity coldspots also provide ecosystem services that humans value at least as much as species diversity. For example, wetlands in the United States are incredibly important for flood control, water purification, wildlife habitat, and recreation. Many wetlands, however, have relatively low plant diversity and, as a result, would not be identified as biodiversity hotspots. It is true that increased species richness leads to improved ecosystem services, but only as we move from very low species richness to moderate species richness. Moving from moderate species richness to high species richness generally does not further improve the functioning of an ecosystem. Since very high species diversity is not expected to provide any substantial improvement in ecosystem function, protecting more and more species produces diminishing returns in terms of protecting ecosystem services. Hence, if our primary goal is to preserve the functioning of the ecosystems that improve our lives, we do not necessarily need to preserve every species in those ecosystems.

How can we reach a resolution?

During the past 2 decades, it has become clear that scientists and policy makers need to set priorities for the conservation of biodiversity. No single criterion may be agreed upon by everyone. However, it is important to appreciate the bias of each approach and to consider the possible unintended consequences of favoring some geographic regions over others. Our investment in conservation cannot be viewed as an all-

Questions

Question 201.1

1. If you were in the role of a decision maker, how might you balance your desire to protect biodiversity around the world with the high cost of preserving biodiversity in any given location?

Question 201.2

2. When identifying hotspots around the world, why is it important to simultaneously consider the biodiversity of different areas and the future human population size in each of these locations?

Question 201.3

3. If you had to make a choice between protecting biodiversity hotspots and biodiversity coldspots, how would you make this decision?

Free-

Florida Reef is the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States. Like other coral reefs on the planet, Florida Reef is home to many species of coral, fish, and other aquatic life forms. Also like other coral reefs, its health is at risk due to such factors as coral bleaching. However, Conservation International does not list this as a biodiversity hotspot.

List two reasons why Florida Reef might not be internationally recognized as a hotspot. (2 points)

List and describe two ecosystem services provided by Florida Reef. (2 points)

What is coral bleaching? (2 points)

Researchers recently found that the disturbance generated by hurricanes is important for maintaining the diversity of coral reef ecosystems. However, massive hurricanes often put many coral reef species at risk of local extinction. Generate a hypothesis to explain this pattern. (4 points)

References

Bacchetta, G., et al. 2012. A new method to set conservation priorities in biodiversity hotspots. Plant Biosystems 146:638–

Joppa, L. N., et al. 2011. Biodiversity hotspots house most undiscovered plant species. PNAS 108:13171–

Kareiva, P., and M. Marvier. 2003. Conserving biodiversity coldspots. American Scientist 91:344–

Myers, N., et al. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403:853–

Orme, C. D., et al. 2005. Global hotspots of species richness are not congruent with endemism or threat. Nature 436:1016–

Key Terms

Endemic species

Biodiversity hotspots