203.1 4scienceapplied

Is There a Way to Resolve the California Water Wars?

Pick up any tomato, broccoli spear, or carrot in the grocery store and chances are it came from California. California’s $37 billion agricultural industry is more than twice the size of the agricultural industry of any other state, and it accounts for nearly one-

Although agriculture in California has been economically successful, it has increased competition among the state’s residents for water. Nearly two-

Wildlife also depends on a readily available supply of fresh water. In many regions of California, diverting water away from streams and rivers threatens the habitats of fish and other aquatic organisms, including several endangered species. Salmon, for instance, require cold, clean water to lay their eggs. In the delta region where the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers come together just east of San Francisco, so much water has been pumped out for use in the southern part of the state that the salmon in the region’s rivers have experienced dramatic declines.

What historical factors have led to California’s water wars?

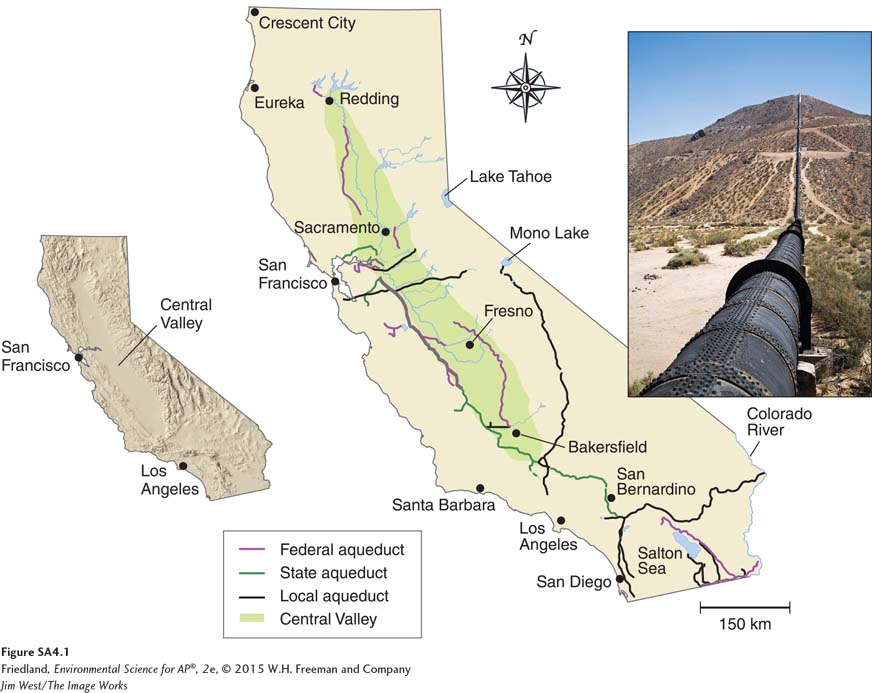

At 144 trillion liters (38 trillion gallons) of fresh water per day, California’s water use is more than twice that of any other state. The vast majority of that water is used in the Central Valley region, which produces more than 80 percent of California’s farm income. In 1935, the U.S. Department of Reclamation began an immense endeavor, called the Central Valley Project, to divert 8.6 trillion liters (2.3 trillion gallons) of water per year from rivers and lakes throughout the state for both agricultural and municipal uses.

While the project made agriculture possible in many of southern California’s desert regions, it also locked into place long-

In 2005, the federal government renewed nearly 200 large water supply contracts with farmers. These contracts were for 25 years, with an option available to extend them another 25 years, at prices so low that the payments did not even cover the cost of the electricity used to transport the water. Organizations ranging from the Cato Institute to the Natural Resources Defense Council protested this decision. The controversy raised the question of whether farmers should continue to be given cheap access to water to protect the existing agricultural industry or be required to pay the same price for water as everyone else.

How might farmers respond to increased water prices?

What would happen if the federal government raised the price of water for California farmers? If water were more expensive, farmers would face four choices: raise the prices of their crops, switch to less water-

One obvious way to offset higher water prices would be for farmers to charge more for the produce they grow. For example, if California broccoli growers had to pay the same price for water as municipalities paid, that cost would add about 13 cents to the price of broccoli per pound—

Other farmers faced with higher water prices might decide to switch to crops that require less water. For example, alfalfa, which uses 25 percent of California’s irrigation water and has a low resale value compared with other crops, would no longer be a profitable crop. A farm using 296 million liters (78 million gallons) of water can produce about $60,000 worth of alfalfa per year, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council. If farmers had to purchase water at the unsubsidized rate, that water would cost them $168,000; if the alfalfa continued to sell for only $60,000, the farmers would lose more than $100,000 a year growing alfalfa. Tomatoes, broccoli, and potatoes use about half as much water per acre as alfalfa and have a higher resale value (FIGURE SA4.2). Just by replacing alfalfa with these crops, California would reduce its statewide water use by 20 percent. This action would have a positive environmental impact, since less overall water would be needed for agriculture in the state.

Investment in new irrigation technology that uses less water would also reduce a farmer’s costs. As we saw earlier in this chapter, the four major irrigation techniques differ in cost and efficiency. If farmers had to purchase water at the unsubsidized rate, converting to more-

If water prices rise, not all farmers will be able to afford the new costs. This recognition brings us to the final option: Some farmers could be driven out of business and forced to sell their land. This outcome would probably reduce the amount of food grown in the region. Whether conversion from farming to other uses would reduce water demand would depend on how the land was used. For example, if it became a housing development in which residents practiced water conservation, then the residents would use much less water per acre than the amount used for agriculture. However, if the residents chose to plant and water large lawns and were not careful about their use of water indoors, they could use even more water than was used for agriculture.

Because charging more for water could force some farmers out of business, many politicians are reluctant to support this change. In response, some economists argue that farmers who possess long-

How have the water wars played out in the political arena?

The California water wars have developed because of the large number of competing interests involved, including northern California farmers and municipalities that are losing water, southern California farmers and municipalities that need more water, endangered species that are declining due to the diversion of water, and beautiful natural areas that have experienced reduced water capacity, seen increased salinity, or gone completely dry.

Competition for California’s water has been marked by political maneuvering and numerous lawsuits. In the 1960s, for example, there was a large push to build dams that would create reservoirs to collect water. Today there are about 1,200 dams in the state. Because of the money and time needed to construct new dams and the environmental impact of dams, many Californians do not consider more dams to be a viable solution to today’s water problems.

The past few years have witnessed a number of lawsuits that have produced very interesting court decisions. For example, the Natural Resources Defense Council won a lawsuit regarding the 2005 water contracts for farmers in the eastern San Joaquin Valley, who use water diverted from the San Joaquin River. The judge ruled that the contracts were illegal because they did not consider how diverting the water might affect endangered species that rely on the river.

In 2007, a federal court was asked to consider how the large, powerful pumps used to divert water from the San Joaquin River and Sacramento delta region affected local fish populations—

The problem of water scarcity in California rose to a crisis level in June 2008 when Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger declared that the state was officially in a drought. As a result of a lack of rain and a reduced amount of snow in the Sierra Nevada, the spring of 2008 was the driest in 88 years. The California legislature passed a bill to cut water use by 20 percent. But the legislature put most of the responsibility for reducing water use on residential users, despite the fact that agriculture uses a much larger portion of the state’s water. Some municipalities started rationing water, and a number of municipalities began enforcing a 2001 state law that requires new building developments to show plans that ensure a 20-

As the drought continued into 2009, additional ideas to promote water conservation were proposed. In June 2009, for example, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power announced that customers who replaced turfgrass with drought-

In November 2009, the California legislature passed a series of bills to address the water crisis. The $40 billion package called for the restoration of the San Joaquin and Sacramento delta ecosystem as well as the building of new dams and a series of water conservation efforts to reduce water demand. A few days later, the governor signed the bill into law.

What can be done?

Given the scarcity of water in California, it stands to reason that its sustainable use is an important topic with many environmental, economic, and even political implications. Economists generally argue that all users should be charged the same amount for a resource so that only those who value it most will pay to use it. Doing so would provide increased motivation for more efficient water use by farms, residences, and businesses. Increased water costs could be helpful in reducing the demand for water, but we cannot forget the simultaneous need for all users to better conserve water.

Scenarios similar to the California water wars are being played out in many other parts of the world. Competition for water exists not only among farmers and municipalities, but also among neighboring countries. Indeed, disagreements over water have turned into real wars between nations. If the competing interests in California can devise creative solutions to the state’s water problems, those solutions can serve as a model for the rest of the world so that we can continue to have economic prosperity without severely harming the environment.

Questions

Question 203.1

1. What are the challenges of balancing the need for water in agriculture with the need for water to protect endangered species?

Question 203.2

2. How might a California farmer who receives subsidized costs of water argue that the current water distribution rules are beneficial not only to farmers but also to society?

Free-

The Los Angeles aqueduct spans 375 km (233 miles) from the Owens Valley through the Mojave Desert to the San Fernando Valley. The aqueduct collects snowmelt from the mountains and is capable of carrying 13.7 m3 of water per second. The water flows the entire distance by gravity. In the years after the aqueduct was completed in 1913, the area in and around Owens Valley has become increasingly dry and farmers have suffered a tremendous loss of productivity.

Surveys taken from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power claim that the water table in the Owens Valley has not changed, yet residents in the Owens Valley claim that wells are running dry. Why might this be? (3 points)

Aside from moving out of the area, list three possible ways that farmers may mitigate the loss of water supply and continue farming. (3 points)

Los Angeles is situated along the shore of the Pacific Ocean. Describe two methods of desalinization that Los Angeles could use to obtain fresh water. List two costs associated with each method. (2 points)

Considering the position of Owens Valley on the windward side of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, how might water diversion through the aqueduct affect air quality in the Owens Valley? (2 points)

References

Martin, G. 2005.The California water wars: Water flowing to farms, not fish. San Francisco Chronicle, October 23.

Steinhauer, J. 2008. Governor declares drought in California. New York Times, June 5.

Obegi, D. 2011. California water wars: It isn’t fish vs. farmers. Los Angeles Times, August 10.