In Chapter 19, we saw that the nations of the world have become concerned about the increasing amount of CO2 in the atmosphere of Earth. While the Kyoto Protocol called for developed nations to reduce total CO2 production, there has been a great deal of debate regarding the most effective way to achieve this reduction.

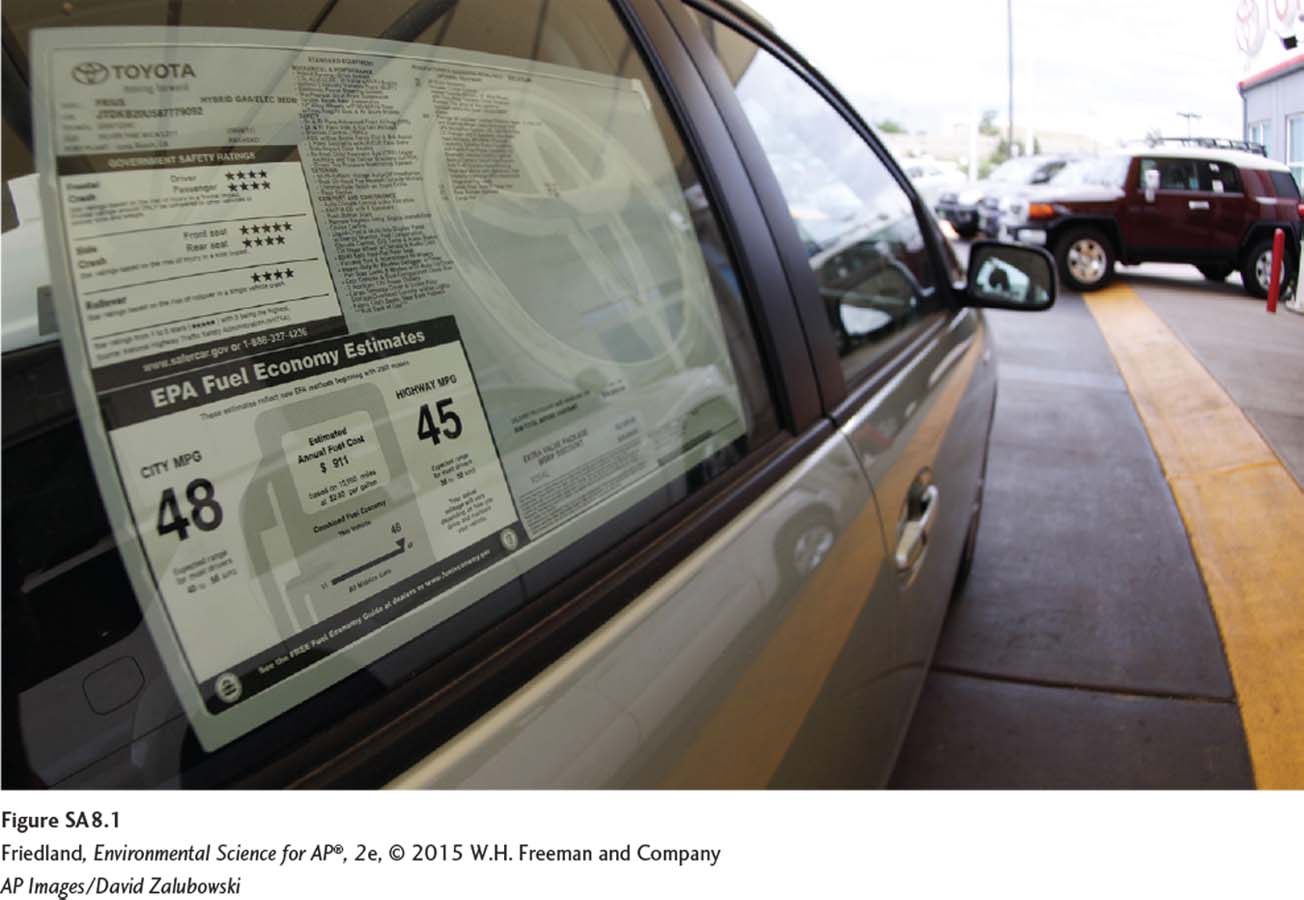

FIGURE 207.1FIGURE SA8.1 The command-and-control approach. When the federal government sets minimum standards for fuel efficiency, it is using a command-and-control approach to pollution.

(AP Images/David Zalubowski)

What are our options for controlling CO2 emissions?

Although many different options for controlling CO2 emissions have been considered, most approaches can be categorized as either command-and-control or cap-and-trade. As discussed in Chapter 20, with a command-and-control approach, a government regulates the amount of pollution that can be emitted by different industries. For example, in 2010 the U.S. federal government announced substantially higher fuel-efficiency standards for cars and light-duty trucks and in 2014 it announced higher standards for medium- and heavy-duty trucks such as delivery trucks and tractor trailers (FIGURE SA8.1). These mandates would reduce the consumption of gasoline and thereby lower the output of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere. The new standards, which ultimately received support from the major automobile manufacturers, require new technology that would make the vehicles more expensive for consumers, but this higher initial expense is more than offset by reduced fuel costs over the life of each vehicle.

Cap-and-trade An approach to controlling CO2 emissions, where a cap places an upper limit on the amount of pollutant that can be emitted and trade allows companies to buy and sell allowances for a given amount of pollution.

While a command-and-control approach means the government sets a single mandatory standard to which all companies must adhere, a cap-and-trade approach uses a different philosophy. As the name suggests, there are two elements to this approach. First, there is a cap, or upper limit, that is placed on the amount of a pollutant that can be emitted. Instead of placing a limit on individual companies or industries, the limit is placed on the total amount of the pollutant produced in a region, such as a state, country, or group of cooperating countries. In the case of CO2, for example, a cap could be placed on the total amount of CO2 that a state or country could emit. To meet the goals of the Kyoto Protocol, for example, the United States agreed to a 7 percent reduction in CO2 from 1990 levels. This value could serve as a cap for the United States.

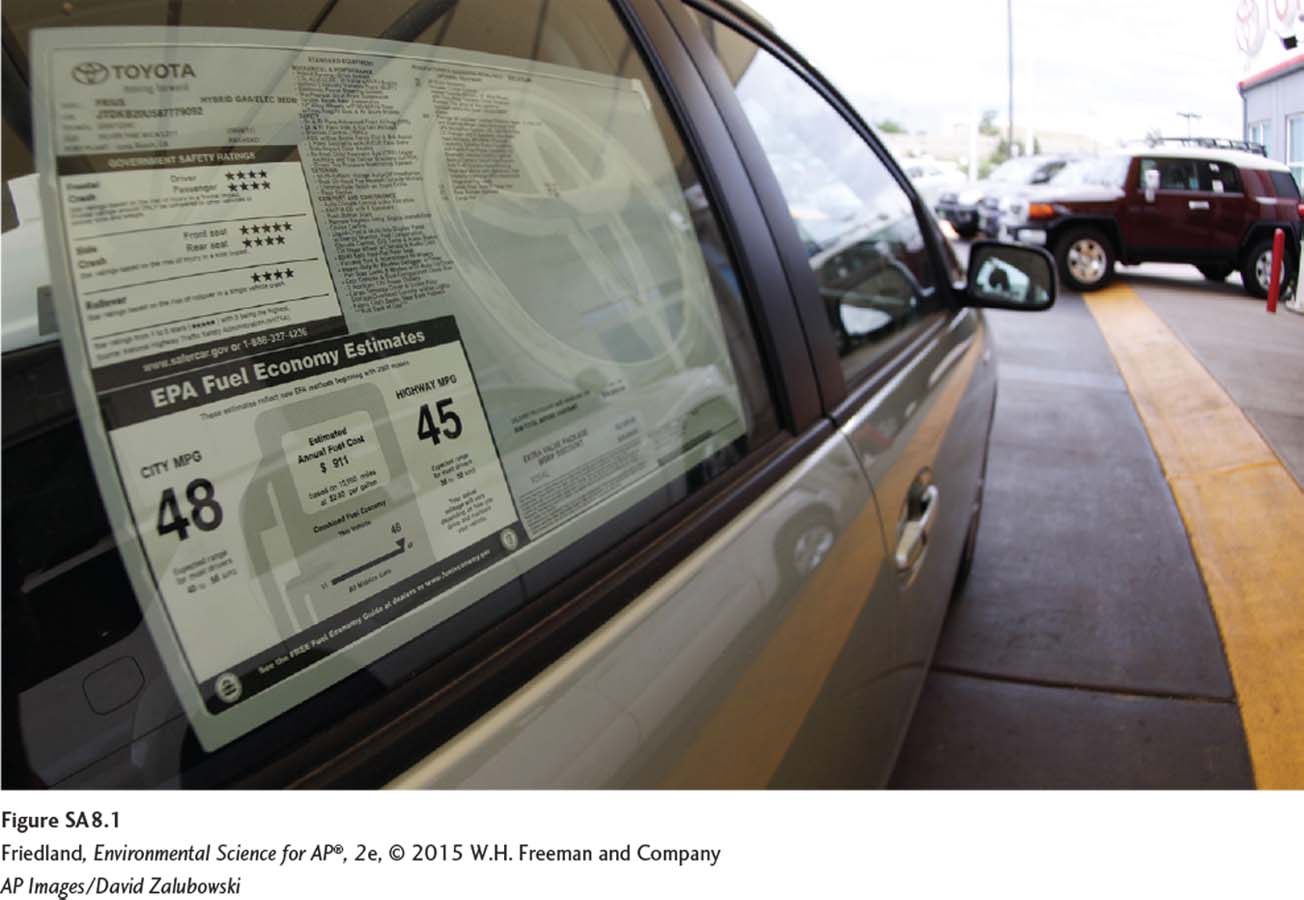

FIGURE 207.2FIGURE SA8.2 Carbon cap-and-trade approach. Many different industries emit large amounts of CO2, including coal-fired electricity-generating power plants, automobiles, airplanes, and steel manufacturers. Under a cap-and-trade approach, all of these industries could be involved in buying and selling permits for CO2 emission.

(top left: David Parsons/iStockphoto.com; bottom left: Elena Elisseeva/age fotostock; right: Digital Vision/Getty Images)

Page 731

The trade portion of the cap-and-trade approach should be familiar from Chapter 15. It allows companies to buy and sell permits for a given amount of pollution. A government can either require all companies that emit pollutants to buy permits or it can distribute a large number of free permits and then slowly reduce the number of permits available to be traded. Allowing companies to buy and sell pollution permits provides an incentive for companies to invest in pollution reduction, since they would gain income by selling permits they no longer need to companies that continue to pollute. Companies still generating large amounts of pollution will also be motivated to reduce their emissions since they would have to spend more to buy the additional permits, assuming that the cost of the permit is higher than the cost of not polluting (FIGURE SA8.2).

Using this strategy, over time, the government would gradually reduce the number of pollution permits available. By the laws of supply and demand, reducing the supply of permits (lowering the cap) causes an increased demand for the remaining permits and results in higher prices for the permits. This price increase further motivates polluting companies to reduce their emissions, resulting in a decline in the total amount of pollution. The cap-and-trade approach avoids the complex regulations that occur with the command-and-control approach and gives companies the freedom to choose from a wide range of possible solutions the approach that best suits them. At the same time, it offers an economic incentive to reduce pollution. The rate at which the pollution declines would depend on how quickly the government reduced the number of pollution permits.

What are the concerns about controlling carbon by using cap-and-trade?

There is currently a great deal of debate concerning the use of cap-and-trade as a means of controlling CO2 emissions. One of the major issues is that most cap-and-trade proposals for CO2 include an additional aspect known as carbon offsets. Carbon offsets are methods of promoting global CO2 reduction that do not involve a direct reduction in the amount of CO2 actually emitted by a company. For example, a company could pay for the reforestation of an area that could absorb CO2 or pay a landowner not to log a forest, thereby keeping the carbon locked up in the biomass of the trees. By paying these costs, a company could avoid paying a potentially higher cost of reducing its own CO2 emissions. Opponents contend that while these efforts would allow a particular piece of land to sequester carbon, it does not decrease the total amount of land needed to grow lumber or crops. As a result, the deforestation simply occurs in another location and the carbon offset does nothing to reduce the global production of CO2. Furthermore, even if a section of land is allowed to sequester carbon, changes in government regulations or political control, or even a natural event such as a forest fire, could rapidly convert sequestered carbon into atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Another concern about the cap-and-trade approach is the exemption of certain companies or facilities. Most experts agree that such exemptions are likely to occur. As we saw in Chapter 15, the cap-and-trade approach was used for the control of sulfur dioxide emissions from coal-powered plants in 1990 to reduce acid precipitation. Many of the older power plants were exempt from the program because at the time it was believed that these plants would soon be retired. However, nearly two-thirds of the coal-powered plants in operation today were constructed before 1975. For cap-and-trade to be a fair system, all polluting companies will need to pay for polluting permits.

Page 732

Has cap-and-trade ever worked successfully?

The concept of cap-and-trade, developed by economists in the 1970s, has experienced limited use in the decades since. As noted above, it was first implemented to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions that caused acid precipitation as part of the U.S. Clean Air Act of 1990. Following a suggestion from the Environmental Defense Fund, the federal government developed a cap-and-trade program for coal-powered plants. Motivated by the new cost of buying pollution permits, the companies owning these plants had to retrofit existing facilities, build new and less polluting facilities, or buy pollution permits from other companies that had already reduced their emissions. Even though some of the older plants were exempt from certain provisions of the act, from 1990 to 2012 there has been a 72 percent reduction in sulfur emissions. The cap-and-trade system motivated investment in new technologies, which is one of the underlying reasons for the success of this program. For example, General Electric developed a system that converted sulfur into gypsum. Because gypsum is a valuable product used in construction, the economic incentive to reduce sulfur emissions motivated new research and development that produced a profitable solution.

In 2005, a carbon cap-and-trade system was instituted in the European Union. Critics of the European system point out that the national governments in the European Union have overestimated the baseline amount of CO2 that their industries were producing and have given away most of the permits to the polluters for free. As a result, these companies have surplus CO2 permits that they can sell at a profit. In rebuttal, proponents of the system point out that this strategy was necessary at the beginning to gain the support of companies. Starting the system with a surplus of permits and then gradually reducing the number of permits available allowed for a gradual adjustment by the companies that emitted CO2. In 2010, the European Union started to lower the cap and more companies, including electricity-generating plants and airlines, began paying for the permits. Some industries, such as steel and cement manufacturers, however, have argued that they needed to continue having free permits if they are to remain competitive with companies that operate outside the European Union. In 2014, the European Union projected that industries covered by the cap-and-trade system would reduce CO2 emissions by 21 percent in 2020 compared with emissions in 2005.

At this stage, it is too early to tell if the cap-and-trade system will be a successful strategy to reduce CO2 emissions. Cap-and-trade was successful in reducing sulfur emissions, but the sulfur program had no offsets that could be used as credit and allow continued pollution by a company. If carbon cap-and-trade is used in the United States, a major focus will be placed on energy companies, including those that produce petroleum products and those that generate electricity. A study by Point Carbon, a market research company, found that the major oil companies, including ExxonMobil and Chevron, would likely pay hundreds of millions of dollars in CO2 permits while electricity-generating companies that have diversified to include hydroelectric and nuclear energy will pay substantially less. Ultimately, if cap-and-trade is successful in the European Union, it could serve as an effective model for other nations and help reduce the growing problem of CO2 and the global changes that come with it.

Question

207.1

1. What is the difference between a command-and-control and a cap-and-trade approach to regulating CO2?

Question

207.2

2. If a cap-and-trade approach were to be used, what is the expected effect on CO2-emitting factories as a nation’s government begins reducing the number of CO2 emission permits?

Write your answer to each part clearly. Support your answers with relevant information and examples. Where calculations are required, show your work.

Carbon taxes provide an alternative method to cap-and-trade for the federal regulation of greenhouse gas emissions. Unlike cap-and-trade, there is no cap on the amount of emissions that can be produced. However, there is a tax on every unit of emissions that is produced. Economists have debated which system is better.

Considering the laws of supply and demand, how is the equilibrium value of pollution permits likely to change? Justify your answer by describing supply and demand curves. Assume a fixed number of permits are given. (2 points)

If a fixed number of pollution permits are distributed in a single year and no more are offered in subsequent years, describe why new companies have a disadvantage under this system. (2 points)

Which of the two methods of regulating greenhouse gas emissions is better if

the environment is highly sensitive to small changes in greenhouse gas emissions? (1 point)

the economy is rapidly growing, and the environment is not highly sensitive to changes in gas emissions? (1 points)

What are carbon offsets and why are they a potential concern in implementing a cap-and-trade system? (2 points)

If a company produces more pollution than allowed by their number of acquired pollution permits, they must pay a fine. Why is the size of the fine important to consider when discussing the potential benefits of cap-and-trade? (2 points)