module 25 Weathering and Soil Science

Soil is a combination of geologic and organic material that forms a dynamic membrane over much of the surface of Earth. A variety of processes that occur in soil connect the overlying biology with the underlying geology. In this module we will explore the weathering of rocks that leads to the formation of soil and the development of specific soil horizons. We will discuss physical, chemical, and biological processes that take place in soils. Finally, we will examine human activities that degrade soils, including the process of mining.

Learning Objectives

After reading this module, you should be able to

understand how weathering and erosion occur and how they contribute to element cycling and soil formation.

explain how soil forms and describe its characteristics.

describe how humans extract elements and minerals and the social and environmental consequences of these activities.

The processes of weathering and erosion contribute to the recycling of elements

We have seen that rock forms beneath Earth’s surface under intense heat, pressure, or both heat and pressure. When rock is exposed at Earth’s surface, it begins to break down through the processes of weathering and erosion. These processes are components of the rock cycle, returning chemical elements and rock fragments to the crust by depositing them as sediments through the hydrologic cycle. This physical breakdown and chemical alteration of rock begins the cycle all over again, as shown in FIGURE 24.15. Without this part of the rock cycle, elements would never be recycled and the precursors of soils would not be present.

Weathering

Weathering occurs when rock is exposed to air, water, certain chemical compounds, or biological agents such as plant roots, lichens, and burrowing animals. There are two major categories of weathering—

Physical weathering The mechanical breakdown of rocks and minerals.

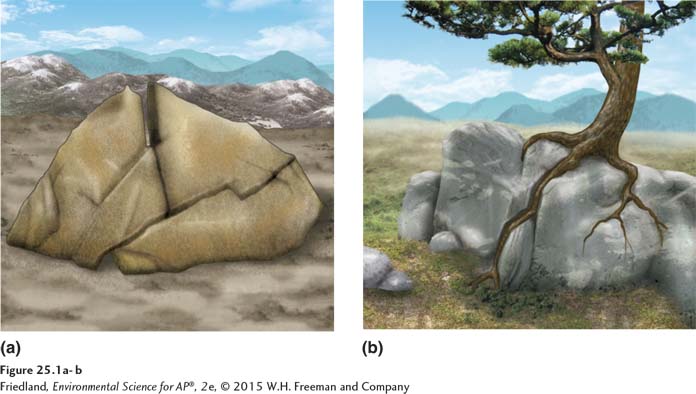

Physical weathering is the mechanical breakdown of rocks and minerals, shown in FIGURE 25.1. Physical weathering can be caused by water, wind, or variations in temperature such as seasonal freeze-

Chemical weathering The breakdown of rocks and minerals by chemical reactions, the dissolving of chemical elements from rocks, or both.

Biological agents can also cause physical weathering. Plant roots can work their way into small cracks in rocks and pry them apart, as illustrated in FIGURE 25.1b. Burrowing animals may also contribute to the breakdown of rock material, although their contributions are usually minor. However it occurs, physical weathering exposes more surface area and makes rock more vulnerable to further degradation. By producing more surface area for weathering processes to act on, physical weathering increases the rate of chemical weathering. Chemical weathering is the breakdown of rocks and minerals by chemical reactions, the dissolving of chemical elements from rocks, or both these processes. It releases essential nutrients from rocks, making them available for use by plants and other organisms.

Chemical weathering occurs most rapidly on newly exposed minerals, known as primary minerals. It alters primary minerals to form secondary minerals and the ionic forms of their constituent chemical elements. For example, when feldspar—

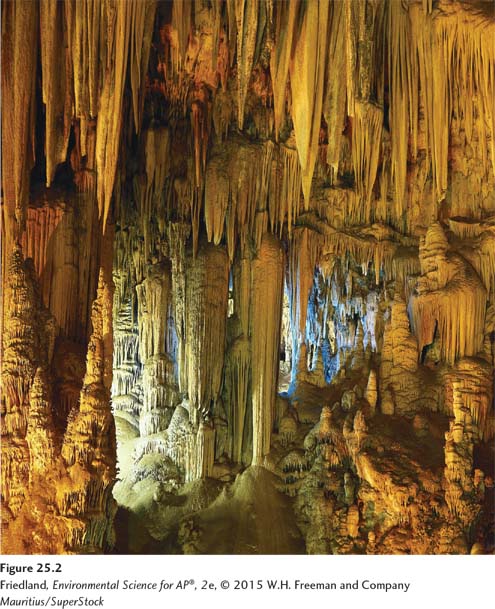

Recall from Chapter 2 that solutions can be basic or acidic. Depending on the starting chemical composition of rock and the pH of the water that comes in contact with it, hundreds of different chemical reactions can take place. For example, as we saw in Chapter 2, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere dissolves in water vapor to create a weak acid, called carbonic acid. When waters containing carbonic acid flow into geologic regions that are rich in limestone, they dissolve the limestone (which is composed of calcium carbonate) and create spectacular cave systems (FIGURE 25.2).

Acid precipitation Precipitation high in sulfuric acid and nitric acid from reactions between water vapor and sulfur and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere. Also known as Acid rain.

Some chemical weathering is the result of human activities. For example, sulfur emitted into the atmosphere from fossil fuel combustion combines with oxygen to form sulfur dioxide. That sulfur dioxide reacts with water vapor in the atmosphere to form sulfuric acid, which then causes acid precipitation. Acid precipitation, also called acid rain, is precipitation high in sulfuric acid and nitric acid from reactions between water vapor and sulfur and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere. Acid precipitation is responsible for the rapid degradation of certain old statues and gravestones and other limestone and marble structures. When acid precipitation falls on soil, it can promote chemical weathering of certain minerals in the soil, releasing elements that may then be taken up by plants or leached from the soil into groundwater and streams.

Chemical weathering, due to either natural processes or acid precipitation, can contribute additional elements to an ecosystem. Knowing the rate of weathering helps researchers assess how rapidly soil fertility can be renewed in an ecosystem. In addition, because the chemical reactions involved in the weathering of certain granitic rocks consume carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, weathering can actually reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

Erosion

Erosion The physical removal of rock fragments from a landscape or ecosystem.

We have seen that physical and chemical weathering results in the breakdown and chemical alteration of rock. Erosion is the physical removal of rock fragments (sediment, soil, rock, and other particles) from a landscape or ecosystem. Erosion is usually the result of two mechanisms. In one, wind, water, and ice move soil and other materials by downslope creep under the force of gravity. In the other, living organisms, such as animals that burrow under the soil, cause erosion. After eroded material has traveled a certain distance from its source, it accumulates. Deposition is the accumulation or depositing of eroded material such as sediment, rock fragments, or soil.

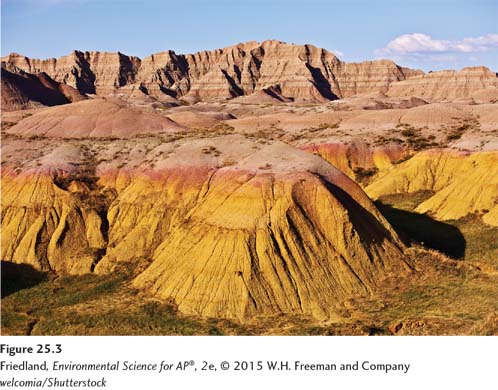

Erosion is a natural process: Streams, glaciers, and wind-

Soil links the rock cycle and the biosphere

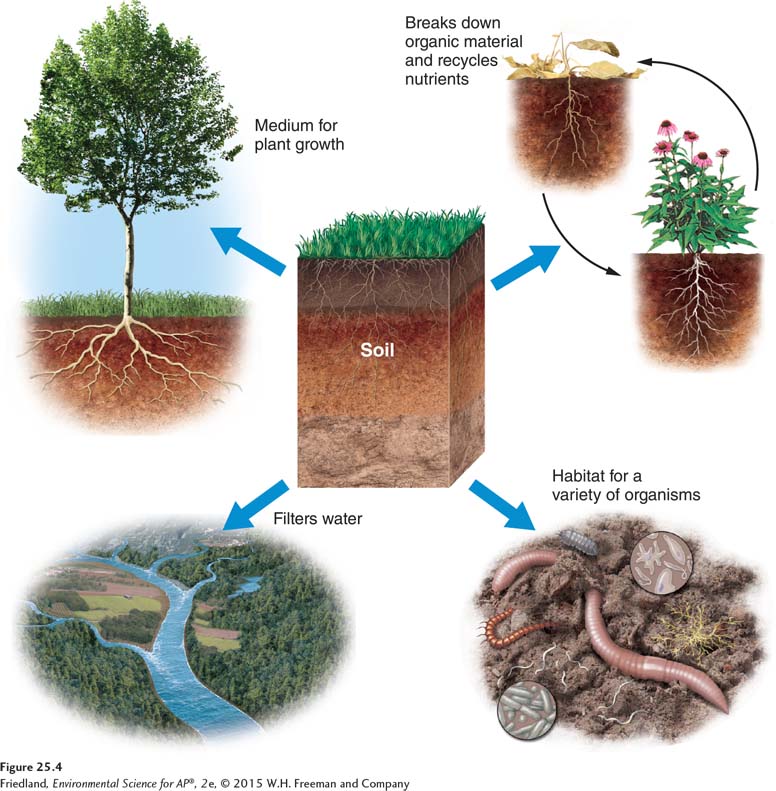

Soil has a number of functions that benefit organisms and ecosystems. As you can see in FIGURE 25.4, soil is a medium for plant growth. It also serves as the primary filter of water as water moves from the atmosphere into rivers, streams, and groundwater. Soil contributes greatly to biodiversity by providing habitat for a wide variety of living organisms—

In this section we will look at the formation and properties of soil.

The Formation of Soil

In order to appreciate the role of soil in ecosystems, we need to understand how and why soil forms and what happens to soil when humans alter it. It takes hundreds to thousands of years for soil to form. Soil is the result of physical and chemical weathering of rocks and the gradual accumulation of detritus from the biosphere. We can determine the specific properties of a soil if we know its parent rock type, the amount of time it has been forming, and its associated biotic and abiotic components.

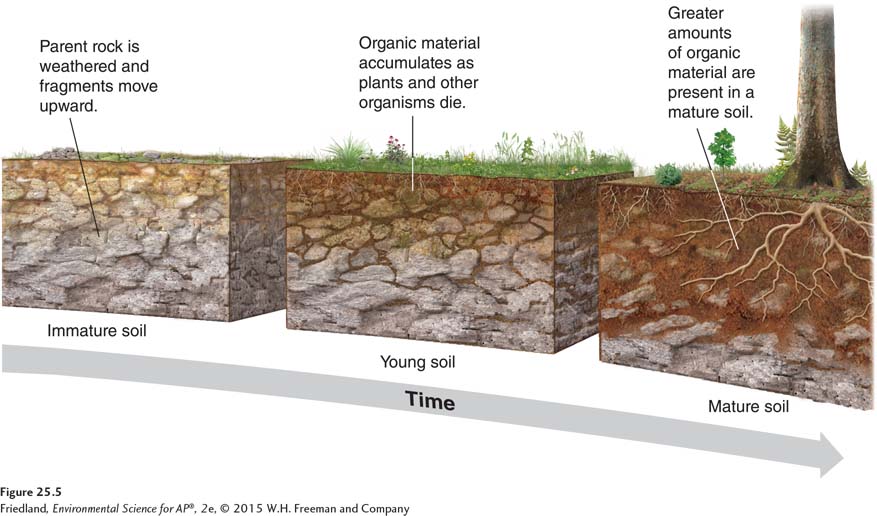

FIGURE 25.5 shows the stages of soil development from rock to mature soil. The processes that form soil work in two directions simultaneously. The breakdown of rocks and primary minerals by weathering provides the raw material for soil from below. The deposition of organic matter from organisms and their wastes contributes to soil formation from above. What we normally think of as “soil” is a mix of these mineral and organic components. A poorly developed (young) soil has substantially less organic matter and fewer nutrients than a more developed (mature) soil. Very old soils may also be nutrient poor because over time plants remove many essential nutrients and water leaches away others. Five factors simultaneously determine the properties of soils: parent material, climate, topography, organisms, and time.

Parent Material

Parent material The rock material from which the inorganic components of a soil are derived.

A soil’s parent material is the underlying rock material from which a soil’s inorganic components are derived. Different soil types arise from different parent materials. For example, a quartz sand (made up of silicon dioxide) parent material will give rise to a soil that is nutrient poor, such as those along the Atlantic coast of the United States. By contrast, a soil that has calcium carbonate as its parent material will contain an abundant supply of calcium, have a high pH, and may also support high agricultural productivity. Such soils are found in the area surrounding Lake Champlain in Vermont and northern New York, as well as in many other locations.

Climate

Climate influences soil formation in a number of ways. Soils do not develop well when temperatures are below freezing because decomposition of organic matter and water movement are both extremely slow in frozen or nearly frozen soils. Therefore, soils at high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere are composed largely of organic material in an undecomposed state, as we saw in Chapter 4. In contrast, soil development in the humid tropics is accelerated by rapid weathering of rock and soil minerals, leaching of nutrients, and decomposition of organic detritus. Climate also has an indirect effect on soil formation because it affects the type of vegetation that develops, and therefore the type of detritus left after the vegetation dies.

Topography

Topography—

Organisms

Many organisms influence soil formation. Plants remove nutrients from soil and excrete organic acids that speed chemical weathering. Animals that tunnel or burrow—

Soil degradation The loss of some or all of a soil’s ability to support plant growth.

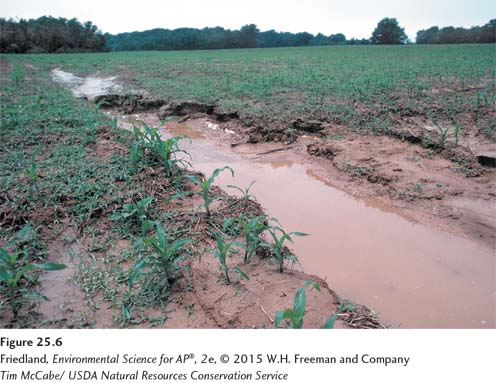

Human activity has dramatic effects on soils. For centuries, the use and overuse of land for agriculture, forestry, and other human activities has led to significant soil degradation: the loss of some or all of the ability of soils to support plant growth. One of the major causes of soil degradation is soil erosion, which occurs when topsoil is disturbed—

While topsoil loss can happen rapidly—

Time

The final factor that determines the properties of a soil is the amount of time during which the soil has developed. As soils age, they develop a variety of characteristics. The grassland soils that support much of the food crop and livestock feed production in the United States are relatively old soils. Because they have had continual inputs of organic matter for hundreds of thousands of years from the grassland and prairie vegetation growing above them, they have become deep and fertile. Other soils that are equally old, but with less productive communities above them and perhaps greater quantities of water moving through them, can become relatively infertile.

Soil Horizons

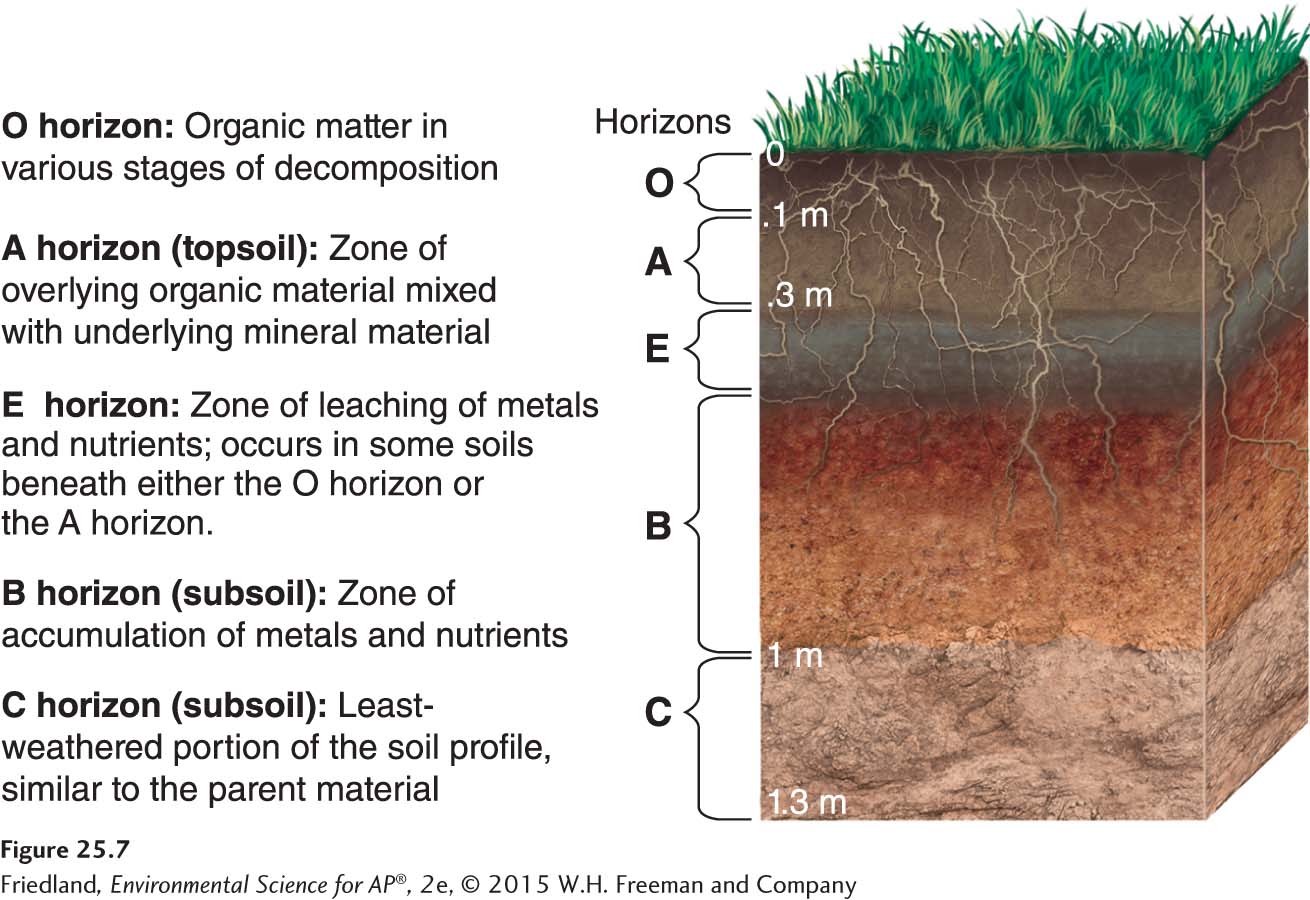

Horizon A horizontal layer in a soil defined by distinctive physical features such as texture and color.

O horizon The organic horizon at the surface of many soils, composed of organic detritus in various stages of decomposition.

As soils form, they develop characteristic horizons, which are horizontal layers with distinct physical features such as color or texture, shown in FIGURE 25.7. The specific composition of those horizons depends largely on climate, vegetation, and parent material. At the surface of many soils is a layer known as the O horizon, composed of organic detritus such as leaves, needles, twigs, and even animal bodies, all in various stages of decomposition. The O horizon is most pronounced in forest soils and is also found in some grasslands. Organic matter is sometimes called humus (pronounced “hu-

A horizon Frequently the top layer of soil, a zone of organic material and minerals that have been mixed together. Also known as Topsoil.

E horizon A zone of leaching, or eluviation, found in some acidic soils under the O horizon or, less often, the A horizon.

B horizon A soil horizon composed primarily of mineral material with very little organic matter.

C horizon The least-

In a soil that is mixed, either naturally or by human agricultural practices, the top layer is the A horizon, also known as topsoil, a zone of organic material and minerals that have been mixed together. In some acidic soils, an E horizon—a zone of leaching, or eluviation—

Properties of Soil

Soils with different properties serve different functions for humans. For example, some soil types are good for growing crops and others are more suited for building a housing development. Therefore, to understand and classify soil types, we need to understand the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soils.

Physical Properties of Soil

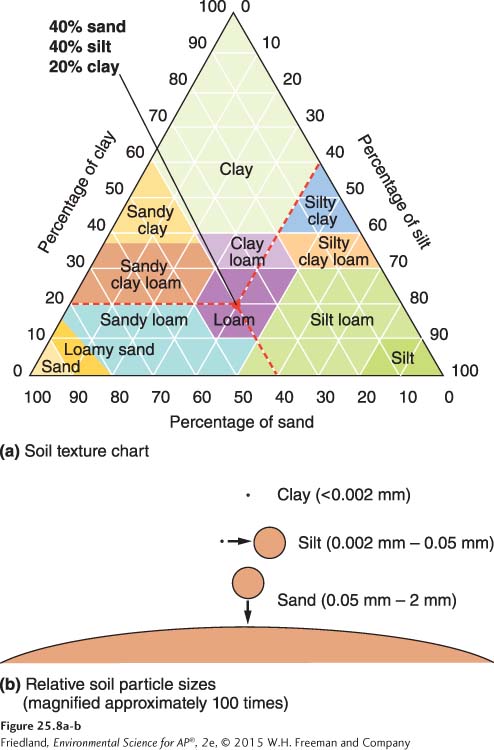

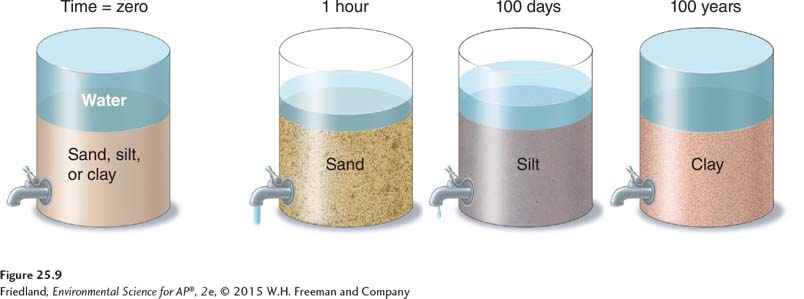

The physical properties of soil refer to features related to physical characteristics such as size and weight. Sand, silt, and clay are mineral particles of different sizes. The texture of a soil is determined by the percentages of sand, silt, and clay it contains. FIGURE 25.8A plots those percentages on a triangle-

The permeability of soil—

The best agricultural soil is a mixture of sand, silt, and clay. This mixture promotes balanced water drainage and retention. In natural ecosystems, however, various herbaceous and woody plants have adapted to growing in wet, intermediate, and dry environments, so there are plants that thrive in soils of virtually all textures.

Soil texture can have a strong influence on how the physical environment responds to environmental pollution. For example, the ground water of western Long Island in New York State has been contaminated over the years by toxic chemicals discharged from local industries. One major reason for the contamination is that Long Island is dominated by sandy soils that readily allow surface water to drain into the groundwater. While soil usually serves as a filter that removes pollutants from the water moving through it, sandy soils are so permeable that pollutants move through them quickly and therefore are not filtered effectively.

Clay is particularly useful where a potential contaminant needs to be contained. Many modern landfills are lined with clay, which helps keep the contaminants in solid waste from leaching into the soil and groundwater beneath the landfill.

Chemical Properties of Soil

Chemical properties are also important in determining how a soil functions. Clay particles contribute the most to the chemical properties of a soil because of their ability to attract positively charged mineral ions, referred to as cations. Because clay particles have a negative electrical charge, cations are adsorbed—

Cation exchange capacity (CEC) The ability of a particular soil to absorb and release cations.

The ability of a particular soil to adsorb and release cations is called its cation exchange capacity (CEC), sometimes referred to as the nutrient holding capacity. The overall CEC of a soil is a function of the amount and types of clay particles present. Soils with high CECs have the potential to provide essential cations to plants and therefore are desirable for agriculture. If a soil is more than 20 percent clay, however, its water retention becomes too great for most crops as well as many other types of plants. In such waterlogged soils, plant roots are deprived of oxygen. Thus there is a trade off between CEC and permeability.

Base saturation The proportion of soil bases to soil acids, expressed as a percentage.

The relationship between soil bases and soil acids is another important soil chemical property. Calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium are collectively called soil bases because they can neutralize or counteract soil acids such as aluminum and hydrogen. Soil acids are generally detrimental to plant nutrition, while soil bases tend to promote plant growth. With the exception of sodium, all the soil bases are essential for plant nutrition. Base saturation is the proportion of soil bases to soil acids, expressed as a percentage.

Because of the way they affect nutrient availability to plants, CEC and base saturation are important determinants of overall ecosystem productivity. If a soil has a high CEC, it can retain and release plant nutrients. If it has a relatively high base saturation, its clay particles will hold important plant nutrients such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium. A soil with both high CEC and high base saturation is likely to support high productivity.

Biological Properties of Soil

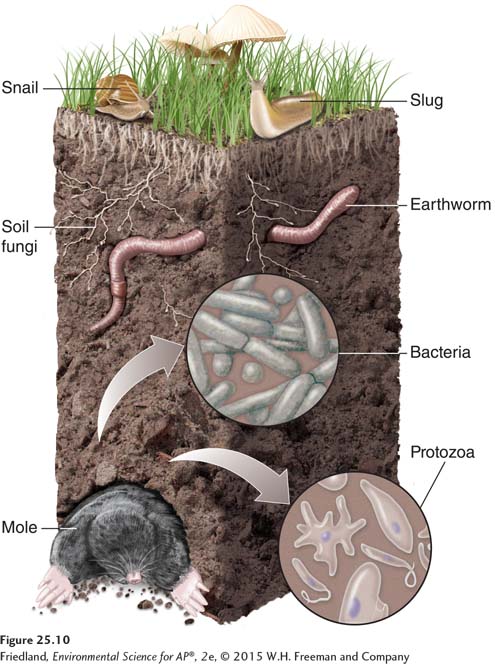

As we have seen, a diverse group of organisms populates the soil. FIGURE 25.10 shows a representative sample. Three groups of organisms account for 80 to 90 percent of the biological activity in soils: fungi, bacteria, and protozoans (a diverse group of single-

The distribution of mineral resources on Earth has social and environmental consequences

The tectonic cycle, the rock cycle, and soil formation and erosion all influence the distribution of rocks and minerals on Earth. These resources, along with fossil fuels, exist in finite quantities, but are vital to modern human life. In this section we will discuss some important nonfuel mineral resources and how humans obtain them; we will discuss fuel resources in Chapters 12 and 13. Some of these resources are abundant, whereas others are rare and extremely valuable.

Abundance of Ores and Metals

Crustal abundance The average concentration of an element in Earth’s crust.

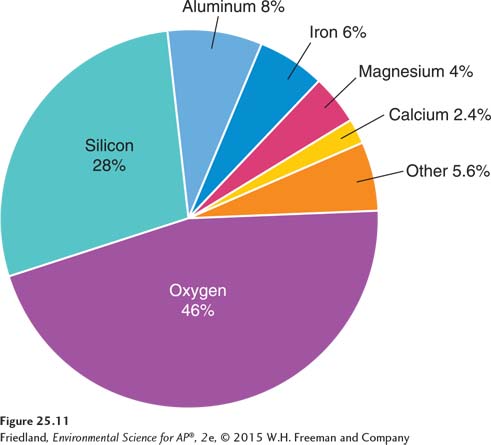

As we saw at the beginning of this chapter, early Earth cooled and differentiated into distinct vertical zones. Heavy elements sank toward the core, and lighter elements rose toward the crust. Crustal abundance is the average concentration of an element in Earth’s crust. Looking at FIGURE 25.11, we can see that four elements—

Ore A concentrated accumulation of minerals from which economically valuable materials can be extracted.

Metal An element with properties that allow it to conduct electricity and heat energy, and to perform other important functions.

Environmental scientists and geologists study the distribution and types of mineral resources around the planet in order to locate them and to manage their extraction or conservation. Ores are concentrated accumulations of minerals from which economically valuable materials can be extracted. Ores are typically characterized by the presence of valuable metals, but accumulations of other valuable materials, such as salt or sand, can also be considered ores. Metals are elements with properties that allow them to conduct electricity and heat energy and to perform other important functions. Copper, nickel, and aluminum are common examples of metals. They exist in varying concentrations in rock, usually in association with elements such as sulfur, oxygen, and silicon. Some metals, such as gold, exist naturally in a pure form.

Ores are formed by a variety of geologic processes. Some ores form when magma comes into contact with water, heating the water and creating a solution from which metals precipitate, while others form after the deposition of igneous rock. Some ores occur in relatively small areas of high concentration, such as veins, and others, called disseminated deposits, occur in much larger areas of rock, although often in lower concentrations. Still other ores, such as copper, can be deposited both throughout a large area and in veins. Nonmetallic mineral resources, such as clay, sand, salt, limestone, and phosphate, typically occur in concentrated deposits. These deposits occur as a result of their chemical or physical separation from other materials by water, in conjunction with the tectonic and rock cycles. Some ores, such as bauxite—

Reserve In resource management, the known quantity of a resource that can be economically recovered.

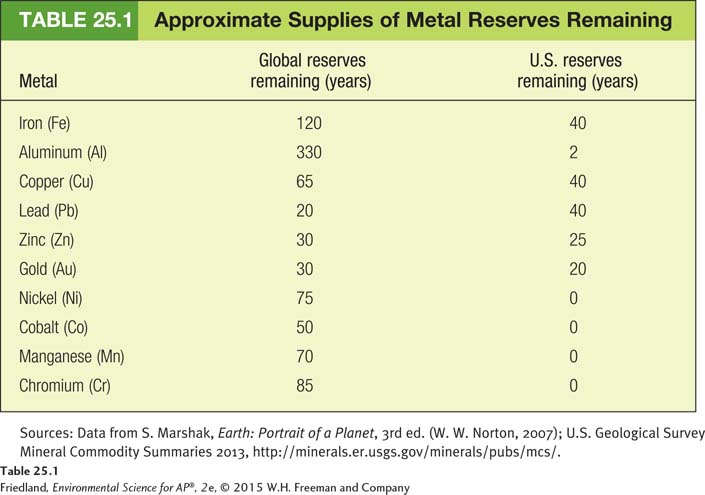

The global supply of mineral resources is difficult to quantify. Because private companies hold the rights to extract certain mineral resources, information about the exact quantities of resources is not always available to the public. The publicly known estimate of how much of a particular resource is available is based on its reserve: the known quantity of the resource that can be economically recovered. TABLE 25.1 lists the estimated number of years of remaining supplies of some of the most important metal resources commonly used in the United States, assuming that rates of use do not change. Some important metals, such as tantalum, have never existed in the United States. The United States has used up all of its reserves of some other metals, such as nickel, and must now import those metals from other countries.

Mining Techniques

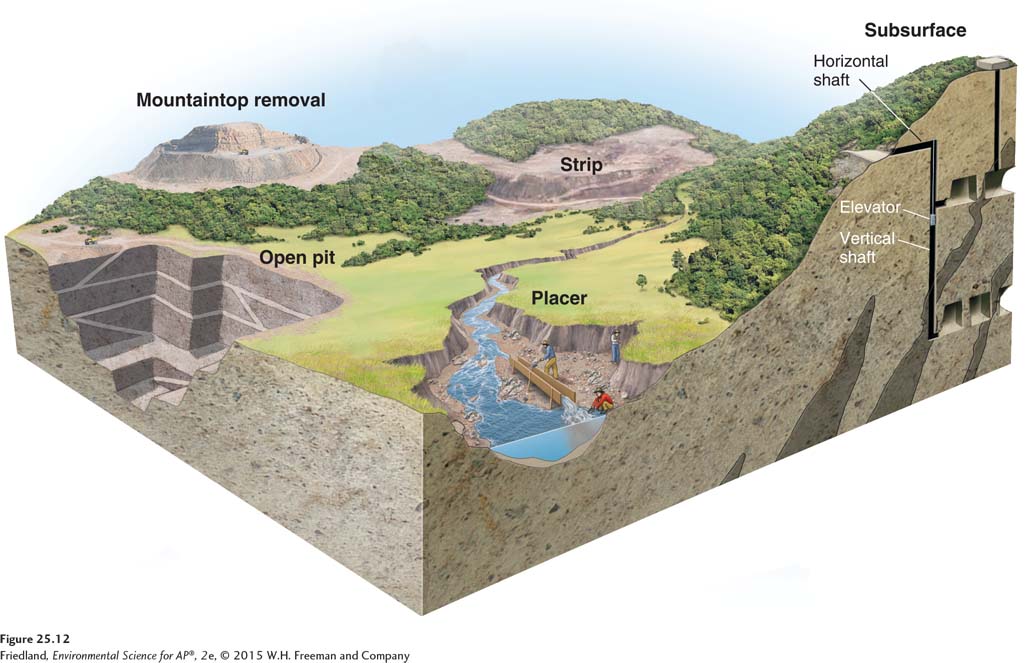

Mineral resources are extracted from Earth by mining the ore and separating any other minerals, elements, or residual rock away from the sought-

Surface Mining

Strip mining The removal of strips of soil and rock to expose ore.

Mining spoils Unwanted waste material created during mining. Also known as Tailings.

A variety of surface mining techniques can be used to remove a mineral or ore deposit that is close to the surface of Earth. Strip mining, or the removal of “strips” of soil and rock to expose the underlying ore, is used when the ore is relatively close to Earth’s surface and runs parallel to it, which is often the case for deposits of sedimentary materials such as coal and sand. In these situations, miners remove a large volume of material, extract the resource, and return the unwanted waste material, called mining spoils or tailings, to the hole created during the mining. A variety of strategies can be used to restore the affected area to something close to its original condition.

Open-

Open-

Mountaintop removal A mining technique in which the entire top of a mountain is removed with explosives.

In mountaintop removal, miners remove the entire top of a mountain with explosives. Large earth-

Placer mining The process of looking for minerals, metals, and precious stones in river sediments.

Placer mining is the process of looking for metals and precious stones in river sediments. Miners use the river water to separate heavier items, such as diamonds, tantalum, and gold, from lighter items, such as sand and mud. The prospectors in the California gold rush in the mid 1800s were placer miners, and the technique is still used today.

Subsurface Mining

Subsurface mining Mining techniques used when the desired resource is more than 100 m (328 feet) below the surface of Earth.

When the desired resource is more than 100 m (328 feet) below Earth’s surface, miners must turn to subsurface mining, which is mining that occurs below the surface of Earth. Typically, a subsurface mine begins with a horizontal tunnel dug into the side of a mountain or other feature containing the resource. From this horizontal tunnel, vertical shafts are drilled, and elevators are used to bring miners down to the resource and back to the surface. The deepest mines on Earth are up to 3.5 km (2.2 miles) deep. Coal, diamonds, and gold are some of the resources removed by subsurface mining.

The Environment and Safety

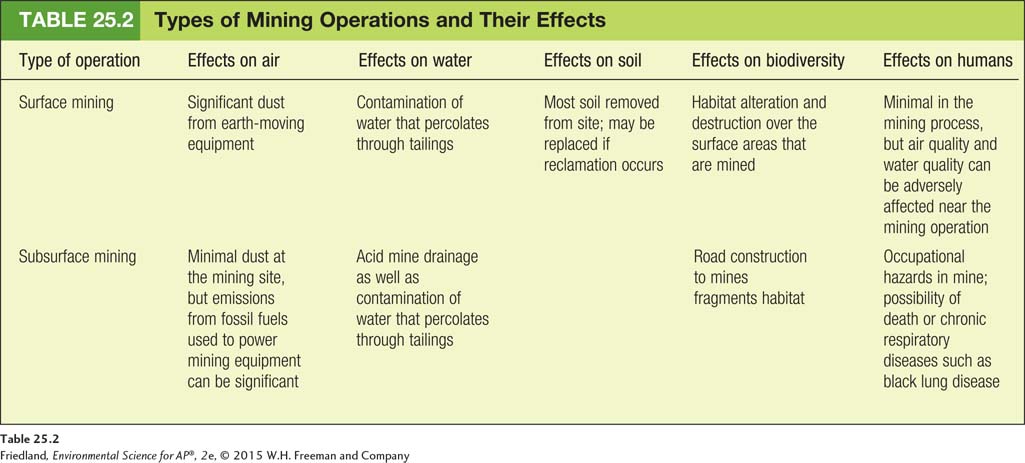

The extraction of mineral resources from Earth’s crust has a variety of environmental impacts on water, soil, biodiversity, and other areas. In addition, mineral resource extraction can have human health consequences that affect the miners directly as well as other individuals who are affected by the mining process.

Mining and the Environment

As you can see in TABLE 25.2 all forms of mining affect the environment. Mining almost always requires the construction of roads, which can result in soil erosion, damage to waterways, and habitat fragmentation. In addition, all types of mining produce tailings, the residue that is left behind after the desired metal or ore is removed, and some tailings contaminate land and water with acids and metals.

In mountaintop removal, the mining spoils are typically deposited in the adjacent valleys, sometimes blocking or changing the flow of rivers. Mountaintop removal is used primarily in coal mining and is safer for workers than subsurface mining. In environmental terms, mining companies do sometimes make efforts to restore the mountain to its original shape. However, there is considerable disagreement about whether these reclamation efforts are effective. Damage to streams and nearby groundwater during mountaintop removal cannot be completely rectified by the reclamation process.

Placer mining can also contaminate large portions of rivers, and the areas adjacent to the rivers, with sediment and chemicals. In certain parts of the world, the toxic metal mercury is used in placer mining of gold and silver. Mercury is a highly volatile metal; that is, it moves easily among air, soil, and water. Mercury is harmful to plants and animals and can damage the central nervous system in humans; children are especially sensitive to its effects.

The environmental impacts of subsurface mining may be less apparent than the visible scars left behind by surface mining. One of these impacts is acid mine drainage. To keep underground mines from flooding, pumps must continually remove the water, which can have an extremely low pH. Drainage of this water lowers the pH of nearby soils and streams and can cause damage to the ecosystem.

Mining Safety and Legislation

Subsurface mining is a dangerous occupation. Hazards to miners include accidental burial, explosions, and fires. In addition, the inhalation of gases and particles over long periods can lead to a number of occupational respiratory diseases, including black lung disease and asbestosis, a form of lung cancer. In the United States, between 1900 and 2006, more than 11,000 coal miners died in underground coal mine explosions and fires. A much larger number died from respiratory diseases. Today, there are relatively few deaths per year in coal mines in the United States, in part because of improved work safety standards and in part because there is much less subsurface mining. In other countries, especially China, mining accidents remain fairly common.

As human populations grow and developing nations continue to industrialize, the demand for mineral resources continues to increase. But as the most easily mined mineral resources are depleted, extraction efforts become more expensive and environmentally destructive. The ores that are easiest to reach and least expensive to remove are always recovered first. When these sources are exhausted, mining companies must turn to deposits that are more difficult to reach. These extraction efforts result in greater amounts of mining spoils and more of the environmental problems we have already noted. Learning to use and reuse limited mineral resources more efficiently will help protect the environment as well as human health and safety.

Governments have sought to regulate the mining process for many years. Early mining legislation was primarily focused on promoting economic development, but later legislation became concerned with worker safety as well as environmental protection. The effectiveness of these mining laws has varied.

Congress passed the Mining Law of 1872 to regulate the mining of silver, copper, and gold ores as well as fuels, including natural gas and oil, on federal lands. This law, also known as the General Mining Act, allowed individuals and companies to recover ores or fuels from federal lands. The law was written primarily to encourage development and settlement in the western United States and, as a result, it contains very few provisions for environmental protection.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 regulates surface mining of coal and the surface effects of subsurface coal mining. The act mandates that land be minimally disturbed during the mining process and reclaimed after mining is completed. Mining legislation does not regulate all of the mining practices that can have harmful effects on air, water, and land. In later chapters we will learn about other U.S. legislation that does, to some extent, address these issues, including the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Superfund Act.