An Annotated Multimedia Research Paper, Laura Hartigan

An Annotated Multimedia Research Paper

Laura Hartigan

Below, we include an example of how one student, Laura Hartigan, used images to accompany her research report on multimodal, creative, and academic writing. An excerpt of her proposal appears in Chapter 11.

Specifically, Laura conducted research and wrote a paper on an issue that she identified in the area of education. More than simply reporting what she found through her observations and interviews, she developed an argument that responded to the following assignment:

Formulate an issue and explain its importance. Remember, at the center of an issue (as opposed to a topic) is a fundamental tension that is open to dispute; this tension can lead to a clear research question.

- Identify a gap reviewing the relevant research. Your review should inform readers about the issue: define key concepts, provide historical background, and discuss methodological issues. Equally important, you should use your review to help readers see a gap in current research and to explain why your study is necessary.

- Justify your methodological approach. You should provide an argument to explain why the methodological approach you take is the best way to answer your research question.

- Analyze the evidence. Your reader will not automatically understand how your evidence fits into the larger picture of your paper. By explaining how the evidence backs up your points, you reveal the logic of the argument and convince even the most skeptical reader.

- Make a claim. The claim is your thesis, and it is central to the argument. What is your position, or what do you want to convince your reader of?

- Support your claim(s) with reasons or evidence. Reasons are the main points of your argument (the “because” part of your argument). What is the basis of the claim you are making?

- Contextualize your claims. Explain how what you find fills a gap or builds upon and extends what others have found. Refer to others’ studies in your discussion and consider how others might respond to what you argue.

Annotated Research Paper

<<COMP: Please set as an annotated research paper and see separate file for popup annotations>>

Understanding the Unique Affordances of Multimodal, Creative Writing and Academic Writing

Laura Hartigan

Abstract

<<COMP: Please number paragraphs per style. STT-LN>>

This study examines student attitudes toward different kinds of writing in in- and out-of-school contexts. The primary purpose is to evaluate the extent to which multimodal, creative, and academic writing afford students the resources to develop authorial identities that have the potential to empower them both in and out of school. When advocating for the inclusion of multimodal, digital literacy practices in the standard curriculum, most studies succeed in revealing the relationship between creative expression and the individual. However, many researchers fail to provide a compelling rationale for why multimodal media literacy should be used in the classroom or explain why such an approach could be integrated into the standard curriculum. The lack of assessment focusing on how academic and multimodal, creative literacies affect one another also reveals a flaw in the conclusions drawn from studies that neglect both spheres of literacy. Without any clear direction for developing innovative curriculum, teachers lack the opportunity to stray from the strictures placed on their classroom by standardized testing. Denied an opportunity to explore the current landscape of multimodality, students lack access to a critical and unique way to develop an authorial presence that extends beyond the strictures, and perhaps insecurities, connected to their authorial voice in academic writing.

Understanding the Unique Affordances of Multimodal, Creative Writing and Academic Writing

Researchers (Hughes, 2009; Vasudevan, Schultz, & Bateman, 2010) have called attention to the unique affordances inherent in creative. For some time now, they have argued for the necessity of including this multimodal mode of writing in the classroom. Within the last decade, even more alternative modes of writing as a means of self-representation and literacy have gained prominence. Studies (Hughes, 2009; Hull & Katz, 2006) argue that multimodal, digital storytelling helps students engage more deeply both with written language and their own personal sense of command over their written work. Allowing for new literate spaces creates the opportunity for multiple modes of learning, understanding, and collaboration rather than isolation in knowledge construction (Hughes, 2009; Hull & Katz, 2006). Typically framed through studies in alternative or out-of-school contexts, studies aim to challenge traditional thinking surrounding curricular and pedagogical practices employed to help students create literate identities.

When advocating for the inclusion of multimodal, digital literacy practices in the standard curriculum, most studies (Hall, 2011; Hughes, 2009; Hull & Katz, 2006; Ranker, 2007; Vasudevan, Schultz, & Bateman, 2010) succeed in revealing evidence to demonstrate a relationship between creative expression and the individual. However, most fail to provide a satisfactory or compelling rationale for why multimodal media and new literacies should be used in the classroom (Alverman, Marshall, McLean, Huddleston, Joaquin, 2012; Binder & Kotsopoulos, 2011; Hull & Katz, 2006; Ranker, 2007) or how the seemingly unique gains could be positively integrated into the standard curriculum. The lack of assessment focusing on how academic and multimodal-digital-creative literacy affect one another reveals a flaw in the conclusions drawn from studies that neglect both spheres of literacy.

Specifically, few articles explore the student’s sense of their literate identity in traditional academic writing versus creative writing. Most researchers (Binder & Kostopoulos, 2011; Hughes, 2009; Hull & Katz, 2006; Vasudevan, Schultz, & Bateman, 2010) reference the mono-literacy landscape of schools in an era of high-stakes testing. As an alternative to an increasingly narrow curriculum in schools, they describe students’ developing sense of authorship and identity when they have opportunities to write, perform, create digital stories, and integrate image and text. However, none probe the binary of academic/creative, or standard/multimodal, writing before, during and after the research study. Such a gap in research seems to necessitate an inquiry into a student’s emergent sense of authorial identity in different forms of composing, even academic writing. One implication would be to show why educators might expand the types of writing/literate experiences that students have in school.

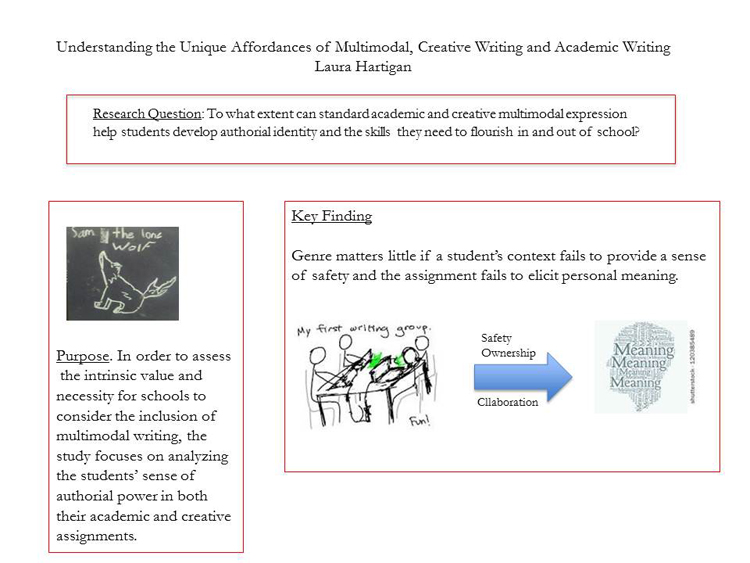

In order to investigate the possible differences between multimodal, creative writing, and standardized academic writing in helping foster students’ voices, this study explores (a) the unique opportunities afforded by the multiple means of expression inherent in multimodal storytelling, (b) how/if these opportunities create an alternative space for the growth of empowered literate identities and a sense of agency, (c) the extent to which writing bring to a student’s development of an authorial voice, (d) why schools should be concerned with the affordances given to the development of a student’s written voice and individual identity by the inclusion of multimodal digital storytelling in the curriculum. In order to assess the intrinsic value and necessity for schools to consider the inclusion of multimodal writing, the study focuses on analyzing the students’ sense of authorial power in both their academic and creative assignments. To what extent can standard academic and creative multimodal expression help students develop authorial identity and the skills they need to flourish in and out of school?

Situating Digital Literacy and Multimodal Writing in the Classroom and Curriculum

In order to gain an understanding of the affordances and importance of digital literacy and multimodality, it is important to design a working construct and definition of digital literacy and multimodal writing. In education, literacy is typically defined as a set of skills and competencies; the abilities to access, understand and create (Buckingham, 2007). However, Buckingham (2007) argues that confining literacy to a list of competencies ignores the interpersonal and critical components of the word. Pointing to a gap in literacy research concerning the new media and technologies, Hall (2011) notes that new forms of literacy are often considered universal rather than framed as socially situated and constructed by people who use different forms of literacy to achieve their own purposes. Literacy does not take place in a vacuum—it is a phenomenon that occurs in cultural, economic, political, historical, and social dimensions and theories (Buckingham, 2007; Hall, 2011; Hughes, 2009; Vasudevan, Schultz, & Bateman, 2010). Thus researchers make an important distinction that I apply here between contexts of writing and contexts of use. It is important to study literacies as they are used to communicate, reflect, and get things done in the world.

Though definitions of literacies range widely, the ability to use multiple forms of literacy is generally defined as being situational, instructional, critical and transformative (Binder & Kotsopoulos, 2011; Ranker, 2007). The current landscape of digital technology has opened up a new field of educational research concerned with the opportunities afforded to students through multimodal engagements in both alternative and classroom spaces. The potential affordances of multimodal venues seem to be numerous. In particular, researchers (Hull & Katz, 2006) focused on the potential for digital and multimodal writing to help individuals enact both identity and agency. Focusing on defining the importance of multimodal opportunities in an alternative literate space, research (Hull & Katz, 2006) has sought to illustrate the way that multiple media and modes combined with a supportive atmosphere of social relationships can provide a powerful route for forming and representing an agentive self. Although research has pointed to the power of new literate spaces and symbolic tools for learning (Hull & Katz, 2006), less research focused on developing these new literate spaces for agentive writing within the classroom. Noting this gap, researchers (Vasudevan, Schultz, & Bateman, 2010) argue that introducing new composing tools for students provides more opportunities for identity exploration and development—particularly involving what it means to be a successful student in the academic classroom space. Likewise, Hughes (2009) argues that utilizing digital literacies in school provides students with opportunities to construct both knowledge and understanding with the new kinds of digital media that figure largely into students’ out-of-school lives. Situating the research even more firmly in the traditional classroom space, Hughes (2009) specifically designates English Language Arts educators with the challenge of providing an alternative space that allows for the freedom of identity exploration and formation.

Understanding the Affordances of Digital Literacy and Multimodality in the Classroom

While multimodality may help students rethink composing processes (Vasudevan, Schultz, & Bateman, 2010), an exploration of varying literacy practices in the classroom demands an analysis of multimodal literacy practices alongside academic literacy practices. Sharpening the ideas drawn from the conclusions of Hughes (2009) points to the necessity of documenting the development of a student’s voice and presence in both multimodal, digital writing and academic writing. Arguing for the inclusion of multimodal literacies in the classroom requires an inquiry into a student’s sense of academic, authorial identity. In essence, I avoid implying that one form of literacy precludes the other. To address this gap, my study will approach the potential affordances of multimodal, digital literacy by analyzing the differences, and perhaps similarities, in how students develop and perceive their authorial presence and power in both kinds of writing—multimodal and academic.

Method

In order to investigate the possible differences and affordances between multimodal, creative writing and academic writing, I conducted an analysis of students’ attitudes about writing in and out of school at a community learning center (CCLC) in a small mid-western city.

Participants

I sampled nine students from the creative writing class of Ms. Smith, a former fourth-grade teacher serving the center as a full-time AmeriCorps member. As an AmeriCorps member, Ms. Smith works in a federal program funded by the state of Indiana for a full-time 40-hour week at the CCLC. Taking place every Wednesday, the creative writing class centers around brainstorming, drafting, and publishing the student work for display inside the center and on a developing Web blog. I chose this specific class and student population because it offered the opportunity to talk to students about their school and afterschool writing experiences alongside the physical creative artifacts they created in Ms. Smith’s class. Due to the participants’ weekly experience of academic tutoring and creative class time, the choice was based on the wide range of writing activities that could be probed by the broad, experience-based focus of the questions I developed for interviews and focus groups.

Data Collection Procedure and Analysis

I conducted the focus groups and interviews with the students in Ms. Smith’s class on separate Fridays over the course of three weeks. I needed parental consent in order to conduct the focus groups and subsequent interviews. Therefore, I emailed consent forms requesting each student’s participation in my research to Ms. Smith two weeks prior to the study’s start in order to provide the necessary time for the forms to be sent home and signed by the parents. Upon receiving confirmation from Ms. Smith that the consent forms had been completed, I began conducting focus groups and interviews with the participating students. The focus groups and interviews took place over the course of two weeks and were conducted during the Friday afterschool sessions at the CCLC. Ms. Smith and the college student volunteers approved a time slot during the Friday sessions to conduct in the CCLC library. The focus groups ranged from 16 to 26 minutes and the one-on-one interviews from 8 to 18 minutes depending on the length and detail of the responses to the scripted questions.

I used an audio recording device to tape the focus groups and interviews. Following the end of each session, I transcribed the recordings over the course of the weekend. Though I opted not to take notes during the focus groups and interviews in order to maintain total engagement with the participants, I typed a series of reflections and field notes immediately after completing each audio recorded session. Following the completion of the transcriptions, I took more notes to identify the thematic patterns crossing conversations in the focus groups and interviews.

Due to the multilayered focus of my research questions, I opted to utilize focus groups, one-on-one-interviews, and participant–observer field notes. Though focus groups invite the potential for peer pressure to encourage or discourage specific responses, I chose this data collection method due to the CCLC’s tenets of safety and openness. The focus groups also allowed me to observe the group dynamics generated from open-ended questions. Following the focus groups, I supplemented the group conversation with one-on-one interviews. The one-on-one interviews allowed the participants to develop ideas and responses free from the influence of their peers. Additionally, the fact that the interviews occurred with past focus group participants provided the opportunity to analyze their group and individual responses to the scripted questions. The interviews also allowed me to directly question students about their attitudes toward physically present creative projects.

After reading the transcripts of the focus groups and interviews, I marked a series of recurring words and ideas in order to develop a set of thematic classifications. After analyzing student responses, I constructed several categories to explore the CCLC participants’ sense of self and authorial identity across contexts: safe spaces, expressing interest and meaningful message, and ownership.

Results

Through conducting and analyzing the two focus groups and three one-on-one interviews based on student experiences and attitudes, I better understood the potential benefits of different modes of writing within different educational spaces. In all instances of primary data collection there were clear and recurrent patterns of students who spoke about the need for safe spaces to write and share their writing, expressing interests in a meaningful way, and ownership. The pervasive thematic importance of the CCLC as a safe, alternative, and family structured element of the participants’ lives indicated the empowerment of fostering a universal sense of dignity and resilience, regardless of subject matter or designated writing styles in academic or creative projects. Rather than different styles of writing dividing along lines of affordances, the three thematic groups connected through students’ feelings about (a) sharing different types of writing assignments in different contexts, (b) the negative emotions associated with standardized, timed writing assignments, and (c) conceptions of their identities in relation to writing, the in-school context, and the CCLC out-of-school context.

An important recurring theme in both the focus groups and interviews was the extent to which a student associated the context of their writing space with a sense of community, respect, and safety. While a student’s sense of comfort and legitimacy in any context may seem to be an obvious factor in their identity as an individual author. But this is not a trivial point. The afterschool, familial nature of the CCLC pointed to the often assumed, or overlooked, affordances of structuring an inherently welcoming, supportive, and alternative space for participants to develop positive, agentive student identities.

Safe Space

In both the focus groups and one-on-one interviews, students expressed an explicit awareness of the CCLC as a safe space and uniformly preferred to perform any kind of writing assignment in a place they found comfortable. Though none of the scripted questions used the word “safe” or targeted the CCLC as the better space to write in, all students indicated that CCLC functioned as a welcoming space outside the differing perceptions of their in-school context. When describing how they felt at the CCLC, one student explained: “It feels like you get to learn new things that you didn’t, that you don’t learn at school.” A fellow member of the focus group supported this student’s claim and said he felt positively about the CCLC, “Because it’s a happy place for me.” Asking students how they felt about writing in school garnered different responses. Some students found that school was not a “fun” place due to a sense of disempowerment. To illustrate this idea, one student in the focus group explained feeling worse at school because: “It’s not as fun as here [the CCLC]. . . . [at school] we get yelled at, we can’t talk about our day when everybody is so loud. And we can’t talk anymore.” Other students supported these feelings by supporting each other’s discussions during the focus groups: “I actually feel different here, like X. I kind of feel better here than at school,” which allowed a chorus of agreement and one student to add, “I feel more like family here.”

When discussing whether or not they would feel comfortable sharing their writing assignments in school or at the CCLC, students revealed an openness to sharing with a group of people they knew and trusted: “If it’s like a different class that I don’t know, then I’m not very comfortable sharing.” After being asked to describe why she liked sharing her work at the CCLC, one student explained: “I like sharing my work at the CCLC because they make me feel welcome and not to be scared of yourself. Like the director says, if you’re scared, just think of like you’re not, nobody’s there.” Recurring ideas of being made to feel safe, accepted, and welcome dominated the conversations. However, questioning students about sharing the CCLC journal creative writing assignment, which contains personal ideas and experiences, revealed a tendency to feel paradoxically that these creative artifacts were private but the CCLC was a safe enough space in which to share private thoughts: “Not if I’m putting personal stuff in it. Well, maybe I would because these people are like my family . . . and my family doesn’t laugh at me.” In a separate focus group, one student supported this awareness of the CCLC as a safe space: “Well, everybody’s like family, so you’re not scared to share stuff with your family, so you shouldn’t be afraid to share it.”

While this represented a general consensus of feelings, other students were comfortable enough to voice different opinions about why they felt comfortable writing in school. Two students indicated that they liked writing in school due to a supportive atmosphere of sharing: “In school I feel comfortable because there is a lot of good ideas going around the room at once.” A second student explained that “I like writing in school because I can do it in groups and I like to discuss my ideas out loud because the person next to me can kind of change them a little but keep them the same.” These responses represented the positive feelings the students could feel about themselves and writing in their in-school context if the classroom structure mirrored the safe and collaborative setup of the CCLC.

The analysis of student responses concerning their willingness to share different writing projects revealed minor instances in which the style of writing affected their feelings of safety and community. Far more prevalent was the importance of how students interpreted the safety of the writing context—both in-school and out-of-school.

Expressing Interests in Meaningful Ways

In writing projects, both creative and academic, students conveyed the importance of expressing their personal interests in assignments as a way to have fun and convey meaning to their audience. The one-on-one interviews offered particularly salient examples of the importance of being able to express matters of personal importance through academic reports or CCLC creative writing projects.

After developing the unfinished plot of a CCLC writing assignment, which consisted of students choosing three random words to write a story, the student who had received, “boy,” “New York,” and “truck” transformed the originally humorous beginning into a much more moral centered story:

I want to also give a message in it that people shouldn’t pick on other kids and, like, kids with disabilities because we were learning about that in school. It’s just terrible what some kids do to other kids with disabilities. And I just really want to put some action and stuff in it. . . . Well, [the main character] learns that he should do others good but even if they’re bad to him, you know, don’t cause other bad things to happen. Because one negative plus a negative . . . well, I guess that equals a positive (laughs). Well, you know, a fight plus a fight doesn’t equal something good.

This student’s acknowledgement of both the creative assignment as a place to express his interest in action and adventure and as a site to deliver a message points to the dual affordances of engaging students in creative writing assignments. Acknowledging the creative story as tool to express his personal beliefs gave the student a sense of authorial legitimacy and importance.

This student also shared a multimodal poem that included written text and a picture about his subject, which was the wolf. Explaining that he wrote a lot during that time due to his interest in the animal, he read the poem’s text: “Your fur is as fluffy as snow./You remind me of your close cousins, dogs./Your howl is sometimes relaxing to hear./You live in such a cold place./How do you survive?/You’re not as vicious as people think,/Are you?” When asked to explain the decision to end the poem with a question, he responded: “Because people . . . I’m just putting it out there that people should ask that question: are they really vicious? Because farmers kill them.” Again acknowledging the meaningful nature of his creative project, the student revealed his ability to express a personal desire to change on the world.

Another student I interviewed discussed the contents of and importance of a CCLC letter to the editor about Earth Day: “We wrote about things we could do to change—to make the world more beautiful. So we wrote they could plant some flowers and trees, turn off the lights to save energy and money, making bigger houses for people, recycling and picking up the trash.” After being asked why she chose the letter as her favorite CCLC writing project, she explained: “Because you got to tell what you wanted to change, what you would like to do for Earth Day.” Similarly, this student liked writing an ode to Hello Kitty since it let her express how she felt about an object that she found important.

While the multimodal assignments at the CCLC continually came up in the interviews, the focus groups brought about a discussion of how students also felt that in-school academic assignments allowed them to express interests. One student expressed that her favorite assignment centered on researching a state for a three-paragraph presentation because: “I just like researching and I only have two books and already found my favorite one because it has a lot of information.” Other students discussed school projects that allowed them to explore various subjects through writing about them, which afforded them a sense of learning and collecting new information. However, when in-school writing assignments related to practicing for standardized, timed, state tests were mentioned, students discussed in-school writing in a more negative manner. In the second focus group the negative implications of feeling restricted by time in a writing assignment revealed itself through the following discussion of timed in-school writing:

Girl a: Because they don’t let me think that much. They’re timed.

Girl b: I don’t like essays cuz they gotta be turned in by a certain date which doesn’t give people long.

Girl c: Um, my least favorite would be writing prompts for ISTEPS because you’ve only got like 25 minutes to get everything planned and then like 15 minutes left to write.

Girl d: That didn’t give me much time either.

The negative feelings associated with timed writing revealed the potential for writing to negatively affect a students’ sense of self as a thinker and developer of ideas.

The first interview, which contained the wolf poems, also revealed a positive association with meaningful writing in conjunction with a negative feeling about in-school writing. The student explained: “I like the CCLC more because I get more of a chance to write . . . because we actually barely write at school and I’m like seriously, we gotta write more, then we actually do things with our hands. Today we dissected fruits. . . . I guess it was fun.” The ending comments about the in-school activities were very sarcastic and the student’s language expressed a frustration with engaging in projects that seemed void of any meaning.

The CCLC as an important alternative space also gained prominence as a meaningful theme in the creative projects of another one-on-one interview. When given the opportunity to choose a potential subject for a poem, the student chose the CCLC. After being asked to explain her choice, she described her own positive feelings toward the CCLC and her desire to bring her experience to other students: “I think the CCLC is a lovely place to go to and [I would] tell them how fun it is and then they might come there next year. . . . I’ll tell them we have a lovely staff here . . . every staff helps them with their homework and [we] have fun projects at the end of tutoring, and Fridays we have all kinds of fun things.” Later in the interview, the student related the personal idea that the CCLC and specifically the creative writing class had helped her grades go up in school:

When I came here we started reading stories with Ms. Smith and she gave us one project and well we had to make a map and then write about it and then all of a sudden I wrote about the girl and she finds a necklace. And then when I got all about writing, my grades came up. Because when, I wasn’t very good at writing at first and then when I came with Ms. Smith she taught us, she helped me out. Yeah and like when we had a test about writing, I did it right and I got an A.

Placing the student’s creative projects against her belief that the writing center helped her gain a stronger in-school writing identity reveals the ability for creative projects to mark sites of deep personal meaning. She conveys the possibility that out-of-school writing experiences can yield positive results in a student’s in-school context.

Ownership

Students provided distinct examples concerning the importance of ownership in their writings and creative expression. When discussing his sense of self as an author, one student stated: “I’m not creative but at the same time I like to mash up a lot of things together at once to make something new.” Though not defining himself as an author, he expressed a positive identity as a constructor and connector of seemingly different ideas. Another student agreed that pulling random ideas together helped him become a better writer. A key recurring idea was the phrase “make our own.” The sense of writing allowing the students to enact an identity of being an individual creator provided them with positive feelings of innovation and development. The focus group conversations revealed the importance of being the creator of something unique in writing. One student said he “like[s] writing fictional stuff, like things that wouldn’t normally exist.” A second student commented that she “like[s] writing about, just random things, funny things, putting things into blobs, saying one thing then making another and then just putting it into one whole collaboration no matter where it goes.” And still another student mentioned that “I have a blank book I could actually make a comic and I’m learning how to draw manga ‘very slowly’ so I can understand how to draw it because manga, it’s just like a whole world.” A pattern emerges from these student responses: creative writing affords students the possibility of designing stories that stretch their imagination and surprise their readers. In the same vein, some students brought up their preference for in-school expository essays and as a way to express arguments and develop their knowledge of various subjects.

During a one-on-one interview, a student expressed the feeling that making the CCLC creative writing assignment “Make Your Own Constellation” was the best one because: “What I liked about it is how we got to make our own story and the stars, the thing, got up in the sky so I made a heart.” The project design allowed students the freedom to choose an object, draw it as a constellation and then write a story about how the constellation came to be in the sky. A number of other students cited this project as their favorite and used the expression “make our own.” The following passage includes the student’s explanation of what she made and what influenced her constellation project (the italics mimic what the student verbally emphasized words during the interview):

Well, I had to make a story about how [to] put art, um, stars in sky. So I made a king who was . . . he saw his daughter with a boy and he didn’t want her to be with him so he broke up love and then threw it in the sky. . . . I only had it when she was with a boy first and then Ms. Smith came over and said probably you should put a little bit more and then I said, oh, and then I saw it lit up in my mind and I said, oh we should have him take away a heart, love. And she said “Yeeeah.”

Even though the student clearly felt guided by the help of Ms. Smith, both the project and the story matter are still marked by a pattern of language that denotes personal ownership and control over the creative project. These patterns emerged across the multiple interviews and focus groups and revealed a collective engagement and positivity toward being ‘makers’ regardless of how the self-identified as authors and writers.

Implications

The stories children tell about writing contribute to developing a more nuanced understanding of the possible affordances that students gain from different kinds of writing in different contexts. Though the study’s original aim and research questions sought to develop a picture of the affordances of multimodal versus academic writing in order to strengthen the rationale for integrating more multimodal practices in the classroom, the results pointed to the fact that the affordances of writing, regardless of type, are inherently connected to a student’s feelings toward the context and space in which the writing takes place. The overarching themes created a portrait, albeit an unexpected one, of how deeply a student’s context informs their sense of the legitimacy of their writings and authorial power. My study adds a concrete element of how the feeling of occupying a safe space informs how students respond to different writing assignments and apply meaning to what they create. Clearly the creative writing class at the CCLC allows the students to explore, develop mystery, surprise, and fun new ideas but the student discussion about academic assignments revealed the ability for more regimented writing to help students develop self-esteem as researchers and learners.

The unexpected shift in focus due to the student responses focused the study’s results less on the affordances of multimodal writing and more toward the necessity for writing to take place in a safe, supportive, meaning centered space. A supportive atmosphere of social relationships truly does provide a safe and powerful avenue for students to develop agency as students, writers, and members of a larger community. With the CCLC’s positive out-of-school context clearly yielding positive effects on the students’ in-school context, once again, my study points to the need for schools to replicate the ways that the CCLC successfully empowers its students to develop multiple and positive academic/personal identities. Based on the student responses, the CCLC as a whole informs the students that they are entering a supportive space similar to their own family. While some students pointed to teachers who managed to create an atmosphere of collaboration and positive social support, many more students revealed that the CCLC helped them develop an identity as a writer that then bled into their in-school experience.

With the overarching theme revealing that genre matters little if a student’s context fails to provide a sense of safety and the assignment fails to elicit personal meaning, my study expands on the notion that the current atmosphere of standardization and tracking truly does impinge upon a student’s sense of authorial power and legitimacy. As one of the quieter students in the focus group passionately said, timed writing takes away their ability to think—and, in my analysis, sense that their thinking matters. While the sampled students are not representative of the larger population in their schools and the CCLC, my study points to the fact that expanding the population in order to probe how students feel about and develop identities as writers across genre and context could provide larger support for studies that assert the need for multimodal practices in the standardized in-school classroom. Changing the focus to how different context affects the student’s multiple sense of identity both in and out-of-school could allow researchers to probe the way an empowering space can facilitate a student’s sense of empowered writing regardless of specific style.

References

Alvermann, D., Marshall, J., McLean, C., Huddleston, A., & Joaquin, J. (2012). Adolescents’ Web-based literacies, identity construction, and skill development. Literacy Research and Instruction, 51(3), 179–195.

Binder, M., & Kotsopoulos, S. (2011). Multimodal literacy narratives: Weaving the threads of young children’s identity through the arts. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 25(4), 339–363.

Buckingham, D. (2007). Digital media literacies: Rethinking media education in the age of the Internet. Research in Comparative and International Education, 2(1), 43–55.

Hall, T. (2011). Designing from their own social worlds: The digital story of three African American young women. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 10(1), 7–20.

Hughes, J. (2009). New media, new literacies and the adolescent learner. E-Learning, 6(3), 259–271.

Hull, G., & Katz, M. (2006). Crafting an agentive self: Case studies of digital storytelling. Research in the Teaching of English, 41(1), 43–81.

Ranker, J. (2007). Designing meaning with multiple media sources: A case study of an eight-year-old student’s writing processes. Research in the Teaching of English, 41(4), 402–434.

Rclc.nd.edu. Retrieved April 27, 2013, from http://rclc.nd.edu/

Vasudevan, L., Schultz, K., & Bateman, J. (2010). Rethinking composing in a digital age: Authoring literate identities through multimodal storytelling. Written Communication, 27(4), 442–468.

<<COMP: Insert: Poster2.pptx>>

<<COMP: Insert: Presentation1.pptx>>

Presentation Poster Guidelines and Sample

If Laura were asked to give a presentation based on her research, she might very well create poster like the one included here, a format that is becoming more common at undergraduate and professional research conferences. The purpose of the poster session is to allow scholars to employ visual forms to initiate conversations about their research. As you plan a poster of your own, the following guidelines might help:

- Decide who your audience is and who want to know about your research

- Determine the key points that you want to convey

- Provide a one-sentence overview of your project

- Create a poster that allows viewers to skim your poster and identify your key ideas

- Use images when possible instead of lots of text

- Keep to the principle of “less is more.” You don’t need to fill your poster with every detail of your research

- Help viewers understand how your research makes a unique contribution to your field of study

For more detail, consult the following websites:

The University of Wisconsin – Madison website at http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/presentations_poster.html

Designing Conference Posters

Michigan State University Faculty and Organizational Development

Analyzing Strategies for Writing

Now that you have read this essay and our annotations, we would like you to answer the following questions in writing or in small groups:

Question 11.1

1. What do you think are the strengths and weaknesses of the ways this writer presented her research? Identify specific concerns you have in the review of relevant research, method, results, and implications.

Question 11.2

2. What have you learned about how to develop a review of relevant research? The level of detail necessary to explain to readers the methods used for collecting and analyzing information from interviews, focus groups, and field notes? The use of examples in presenting results and drawing conclusions in the implications section of an essay like this?

Question 11.3

3. What would you do differently in writing up your own study?

<<textbox>>

<<Settings>>