Faulty Reasoning and Logical Fallacies

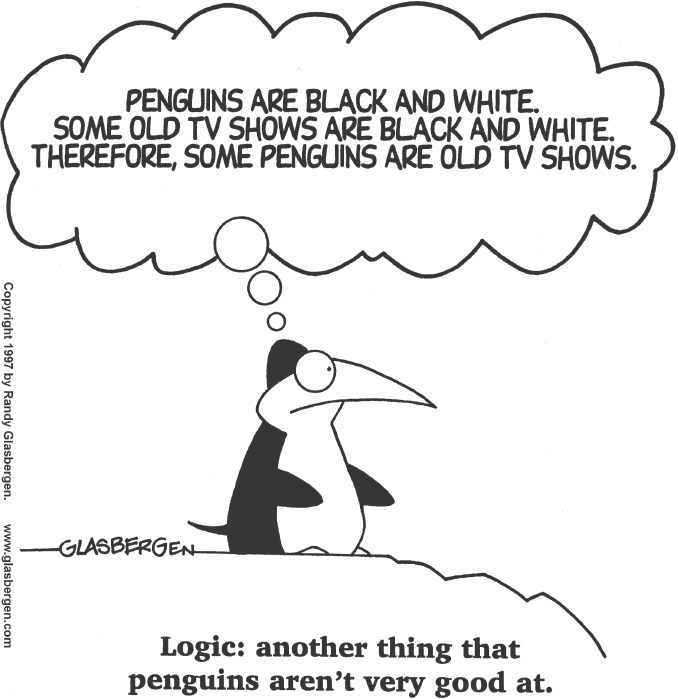

A critical thinker has a healthy attitude of wanting to avoid nonsense, to find the truth, and to discover the best course of action. Logical reasoning is essential to solving any problem, whether simple or complex. A critical thinker needs to go one step further to check that an argument hasn’t been based on any logical fallacies, which are mistakes in reasoning that contain invalid arguments or irrelevant points that weaken the logic of an argument. When confronted with logical fallacies, critical thinkers aim to be logical instead of defensive or emotional.

Here are some of the most common logical fallacies:

- Attacking the person. It’s perfectly acceptable to argue against other people’s positions or to attack their arguments. It is not acceptable, however, to go after their personalities. Any argument that resorts to personal attack (“Why should we believe a cheater?”) shouldn’t be considered.

- Appealing to emotion. “Please, officer, don’t give me a ticket because if you do, I’ll lose my license, and I have five little children to feed and won’t be able to feed them if I can’t drive my truck.” None of the driver’s statements offer any evidence, in any legal sense, as to why she shouldn’t be given a ticket. Appealing to emotion might work if the officer is feeling generous, but an appeal to facts and reason would be more effective: “I fed the meter, but it didn’t register the coins. Because the machine is broken, I’m sure you’ll agree that I don’t deserve a ticket.”

- Arguing along a slippery slope. “If we allow college tuition to increase by 2 percent, the next thing we know it will have gone up 200 percent a term.” Such an argument is an example of slippery slope thinking: claiming that one small event will definitely lead to a larger, more significant event without allowing for the possibility of other alternatives.

- Appealing to false authority. Citing authorities, such as experts in a field or qualified researchers, can offer valuable support for an argument, but a claim based on the authority of someone who isn’t an expert only gives the appearance of authority rather than real evidence. Many ads that use celebrity spokespeople reply on such appeals.

- Jumping on a bandwagon. Sometimes we are more likely to believe something that many others also believe. Even the most widely accepted truths, however, can turn out to be wrong. At one time, nearly everyone believed that the sun revolved around the earth—until astronomers proved that the sun is at the center of the solar system and the earth revolves around it.

- Assuming that something is true because it hasn’t been proved false. Go to a bookstore or online, and you’ll find dozens of books claiming to report close encounters with flying saucers and extraterrestrial beings or ghosts. Because critics could not disprove the claims of the witnesses, the events are said to have really occurred. Even if you can’t completely prove that something is false, you can question the evidence.

- Falling victim to false cause. Frequently, people assume that just because one event followed another, the first event must have caused the second. This reasoning is the basis for many superstitions. The ancient Chinese once believed that they could make the sun reappear after an eclipse by striking a large gong, because they knew that one time the sun reappeared after a large gong had been struck. Most effects, however, are usually the result of a complex web of causes. Don’t be satisfied with easy before-and-after claims; they are rarely correct.

- Making hasty generalizations. If you selected one green marble from a barrel containing a hundred marbles, would you guess that the next marble would be green? There are ninety-nine marbles still in the barrel; they could be any color. If, however, you had drawn fifty green marbles from the barrel, you might conclude that the next marble you draw would be green, too. (Of course, you would still have to be careful; the next marble might be a different color after all.) Reaching a conclusion based on one instance or one source is like figuring that all the marbles in the barrel are green after pulling out only one.

Fallacies like these can slip into even the most careful reasoning when someone is trying to make a point. One false claim can change an entire argument, so be on the lookout for weak logic in what you read, write, hear, or say. Check the facts presented in an argument. Do not just accept them because several other people do. Remember that accurate reasoning is a key factor for success in college and in life.

YOUR TURN > DISCUSS IT

Have you ever used or heard someone use any of these logical fallacies to justify a decision? Why was it wrong to do so?