10.2 DEVELOPING STRONG THINKING SKILLS

As you’ve read, a high-priority goal in college is to develop strong thinking and decision-making skills. Having these skills will help you become a competent and confident individual who is capable of contributing to the larger society by helping solve community and national problems. There are steps you can take to develop these skills.

Ask Questions

The first step of thinking at a deeper level, of true critical thinking, is to be curious. This involves asking questions. Instead of accepting statements and claims at face value, question them. Here are a few suggestions:

When you come across an idea or a statement that you consider interesting, confusing, or suspicious, first ask yourself what it means.

Do you fully understand what is being said, or do you need to pause and think to make sense of the idea?

Do you agree with the statement? Why or why not?

Can the statement or idea be interpreted in more than one way?

Don’t stop there.

Ask whether you can trust the person or group making a particular claim, and ask whether there is enough evidence to back up that claim (more on this later).

Ask who might agree or disagree and why.

Ask how a new concept relates to what you already know.

Think about where you might find more information about the subject, and what you could do with what you learn.

Ask yourself about the effects of accepting a new idea as truth.

Will you have to change or give up what you have believed for a long time?

Will it require you to do something differently?

Will it be necessary to examine the issue further?

Should you try to bring other people around to a new way of thinking?

Consider Multiple Points of View and Draw Conclusions

Before you draw any conclusions about the validity of information or opinions, it’s important to consider more than one point of view. College reading assignments might deliberately expose you to conflicting arguments and theories about a subject, or you might encounter differences of opinion as you do research for a project. Your own belief system will influence how you interpret information just as others’ belief systems and points of view might influence how they present information. For example, consider your own ideas about the cost of higher education in the United States. American citizens, politicians, and others often voice opinions on tuition and fees at two-year versus four-year colleges and universities and even whether college should be free. What do you think should be done about the cost of college, if anything, and why do you hold this viewpoint?

The more ideas you consider, the better your thinking will become. Ultimately, you will discover not only that it is OK to change your mind but also that a willingness to do so is the mark of a reasonable, educated person. Considering multiple points of view means synthesizing material, evaluating information and resources that might contradict each other or offer multiple points of view on a topic, and then honoring those differences.

As you begin to draw conclusions based on the many viewpoints and other types of evidence you’ve explored, you need to look at the outcome of your inquiry in a more demanding, critical way. In a chemistry lab, it might be a matter of interpreting the results of an experiment. In buying a tablet, it might require evaluating your needs and your budget, asking others about their experiences, and reading buyers’ reviews.

If you are looking for solutions to a problem, which ones seem most promising after you have conducted an exhaustive search for materials? If you have found new evidence, what does it show? Does what you are learning motivate you to investigate more about your topic? Do your original beliefs still hold up, or do you think they need to be modified or abandoned? Most important, consider what you would need to do or say to persuade someone else that your ideas are valid. Thoughtful conclusions are the most useful when you can share them with others.

After considering multiple viewpoints and drawing conclusions, the next step is to develop your own views based on credible evidence and facts, while staying true to your values and beliefs. Critical thinking is the process you go through in deciding how to align your experience and value system with your viewpoint. The end-game isn’t to arrive at the “right” answer but rather the one that you think is the most practical, or it might be a new idea of your own creation.

YOUR TURN > DISCUSS IT

Our experiences shape the way in which we think about the world around us. Name three people (such as family members, friends, coaches, religious leaders, celebrities, national figures) who have most influenced the way you think. Describe how these individuals’ values, actions, expectations, and words have shaped the way you think about yourself and the world. Have any of them influenced your purpose for being in college?

Make Arguments

What does the word argument mean to you? If you’re like most people, the first image it brings up might be an ugly fight you had with a friend, a yelling match you witnessed on the street, or a heated disagreement between family members. True, such unpleasant confrontations are arguments, but the word also refers to a calm, reasoned effort to persuade someone of the value of an idea.

When you think of it this way, you’ll quickly recognize that arguments are central to academic study, work, and life in general. Scholarly articles, business memos, and requests for spending money all have something in common: The effective ones make a general claim, provide reasons to support it, and back up those reasons with evidence. That’s what argument is.

It’s important to consider different arguments in tackling new ideas and complex questions, but arguments are not all equally valid. Whether examining an argument or making one, a good critical thinker is careful to ensure that ideas are presented in an understandable, logical way.

Challenge Assumptions and Beliefs

To some extent, it’s unavoidable to have beliefs based on gut feelings or blind acceptance of something you’ve heard or read. However, some assumptions should be examined more thoughtfully, especially if they will influence an important decision or serve as the foundation for an argument.

We develop an understanding of information based on our value systems and how we view the world. Our family backgrounds influence these views, opinions, and assumptions. College is a time to challenge those assumptions and beliefs and to think critically about ideas we have always had.

Well-meaning people will often disagree. It’s important to listen to both sides of an argument before making up your mind. If you follow the guidelines in this chapter, you will have critical-thinking skills to figure things out instead of depending purely on how you feel or what you’ve heard. As you listen to a lecture, debate, or political argument about what is in the public’s best interest, try to predict where it is heading and why. Ask yourself whether you have enough information to justify your own position.

YOUR TURN > DISCUSS IT

Have you ever read a book or watched a movie introducing ideas that made you question your own thinking or your opinions about something? Discuss your experience in class and explain how those ideas changed your way of thinking.

Examine Evidence

Another important part of thinking critically is checking that the evidence supporting an argument—whether someone else’s or your own—is of the highest possible quality. To do that, simply ask a few questions about the argument as you consider it:

What general idea am I being asked to accept?

Are good and sufficient reasons given to support the overall claim?

Are those reasons backed up with evidence in the form of facts, statistics, and quotations?

Does the evidence support the conclusions?

Is the argument based on logical reasoning, or does it appeal mainly to emotions?

Do I recognize any questionable assumptions?

Can I think of any counterarguments, and if so, what facts can I use as proof?

What do I know about the person or organization making the argument?

What credible sources can I find to support the information?

If you have evaluated the evidence used in support of a claim and are still not certain of its quality, it’s best to keep looking for more evidence. Drawing on questionable evidence for an argument has a tendency to backfire. In most cases, a little persistence will help you find better sources.

Recognize and Avoid Faulty Reasoning

Although logical reasoning is essential to solving any problem, whether simple or complex, you need to go one step further to make sure that an argument hasn’t been compromised by faulty reasoning. Here are some of the most common missteps—referred to as logical fallacies or flaws in reasoning—that people make in their use of logic:

Attacking the person. Arguing against other people’s positions or attacking their arguments is perfectly acceptable. Going after their personalities, however, is not OK. Any argument that resorts to personal attack (“Why should we believe a cheater?”) is unworthy of consideration.

Begging. “Please, officer, don’t give me a ticket! If you do, I’ll lose my license, and I have five little children to feed, and I won’t be able to feed them if I can’t drive my truck.” None of the driver’s statements offer any evidence, in any legal sense, as to why she shouldn’t be given a ticket. Pleading might work if the officer is feeling generous, but an appeal to facts and reason would be more effective: “I fed the meter, but it didn’t register the coins. Since the machine is broken, I’m sure you’ll agree that I don’t deserve a ticket.”

Appealing to false authority. Citing authorities, such as experts in a field or the opinions of qualified researchers, can offer valuable support for an argument. However, a claim based on the authority of someone whose expertise is questionable relies on the appearance of authority rather than on real evidence. We see examples of false authority all the time in advertising: Sports stars who are not doctors, dietitians, or nutritionists urge us to eat a certain brand of food; famous actors and singers who are not dermatologists extol the medical benefits of a costly remedy for acne.

Jumping on a bandwagon. Sometimes we are more likely to believe something that many others also believe. Even the most widely accepted truths can turn out to be wrong, however. At one time, nearly everyone believed that the earth was flat, until someone came up with evidence to the contrary.

Assuming that something is true because it hasn’t been proven false. If you go to a library or look online, you’ll find dozens of books detailing close encounters with flying saucers or ghosts. These books describe the people who had such encounters as completely honest and trustworthy. Because critics could not disprove the claims of the witnesses, the events are said to have actually occurred. Even in science, few things are ever proved completely false, but evidence can be discredited.

Falling victim to false cause. Frequently, we make the assumption that just because one event followed another, the first event must have caused the second. This reasoning is the basis for many superstitions. The ancient Chinese once believed that they could make the sun reappear after an eclipse by striking a large gong because they knew that on a previous occasion the sun had reappeared after a large gong had been struck. Most effects, however, are usually the result of several causes. Don’t be satisfied with easy before-and-after claims; they are rarely correct.

Making hasty generalizations. Sometimes it is tempting to draw a conclusion based on a few anecdotes or limited evidence. For instance, if your high-school-age sister and some of her friends were scrambling to get tickets to a Zendaya concert, could you assume that all teenage girls are Zendaya fans? Generalizations based on only a few examples are almost always inaccurate. Can you think of times when you have been guilty of this?

Slippery slope. “If we allow tuition to increase, the next thing we know, it will be $20,000 per term.” Such an argument is an example of “slippery slope” thinking. Fallacies like these can slip into even the most careful reasoning. One false claim can derail an entire argument, so be on the lookout for weak logic in what you read and write. Never forget that accurate reasoning is a key factor in succeeding in college and in life.

YOUR TURN > DISCUSS IT

Have you ever used or heard someone use any of these logical fallacies to justify a decision? Do logical fallacies sometimes persuade others of the truth of an argument? Share an example with the class, and discuss why people use logical fallacies.

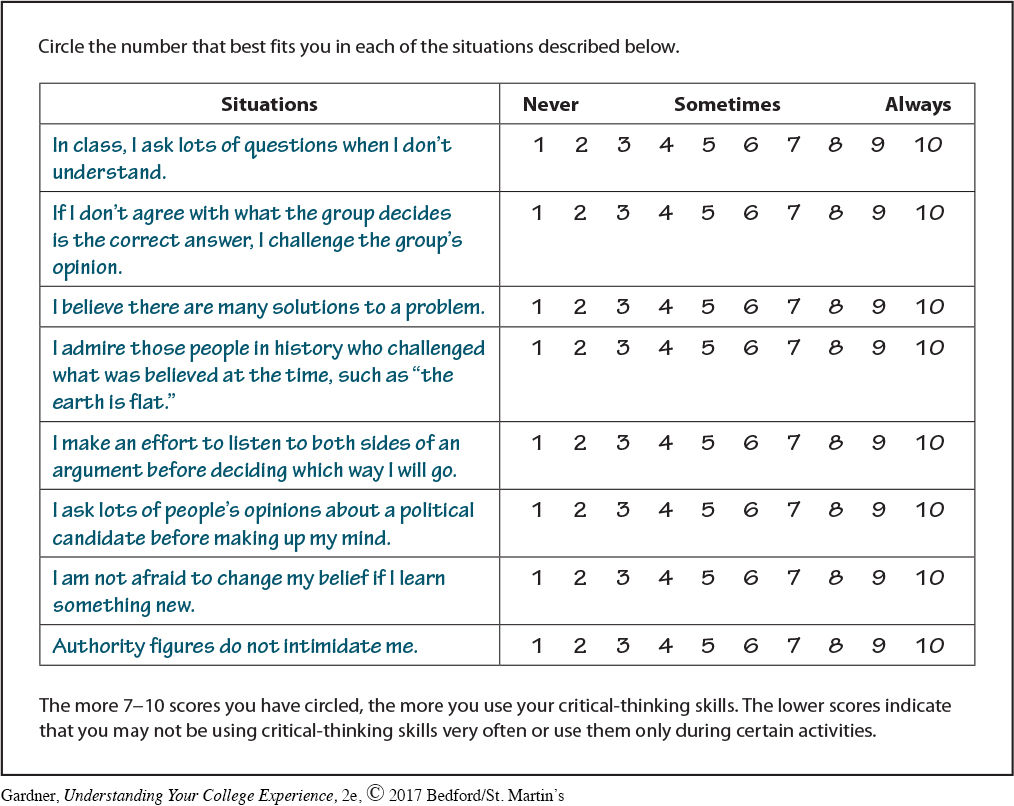

Now that you have read about critical thinking, it would be beneficial to rate yourself as a critical thinker. Use Figure 10.1 to rate your critical-thinking skills.