6.1 A PLAN FOR ACTIVE READING

Active reading involves participating in reading by using strategies, such as highlighting and note taking, which help you stay focused. Active reading is different from reading novels or magazines for pleasure, which doesn’t require you to do anything while you are reading. Active reading will increase your focus and concentration, help you understand what you read, and prepare you to study for tests and exams. These are the four steps in active reading designed to help you read college textbooks:

Previewing

Marking

Reading with concentration

Reviewing

YOUR TURN > WORK TOGETHER

With a group of your classmates, discuss which of these four steps you always, sometimes, or never take. Have one member of the group keep a tally and report results to the class. Which steps, if any, do your classmates think are necessary, and why?

Previewing

Previewing is the step in active reading where you develop a purpose for reading and take a first look at an assigned reading before you really tackle the content. Think of previewing as browsing in a newly remodeled store. You locate the pharmacy and grocery areas. You get a feel for the locations of the men’s, women’s, and children’s clothing departments; housewares; and electronics. You pinpoint the restrooms and checkout areas. You get a sense for where things are in relation to each other and compared to where they used to be. Then you focus on your purpose for coming to the store and identify where to find the items that you buy most often, whether they are diapers, milk, school supplies, or prescriptions. You get oriented.

Previewing a chapter in your textbook or other assigned reading is similar: The purpose is to get the big picture, to understand the main ideas in the reading and how those ideas connect with what you already know and to the material the instructor covers in class. Here’s how you do it:

Begin by reading the title of the chapter. Ask yourself: What do I already know about this subject?

Next, quickly read through the learning objectives, if the chapter has them (usually stated as the chapter begins—or check the course syllabus), or the introductory paragraphs. Learning objectives are the main ideas or skills students are expected to learn from reading the chapter.

Then turn to the end of the chapter and read the summary if there is one. A summary provides the most important ideas in the chapter.

Finally, take a few minutes to skim the chapter, looking at the headings, subheadings, key terms, and tables and figures. Look for study exercises at the end of the chapter.

As part of your preview, note how many pages the chapter contains. It’s a good idea to decide in advance how many pages you can reasonably expect to cover in your first study period. This can help build your concentration as you work toward your goal of reading a specific number of pages. Before long, you’ll know how many pages are practical for you to read at one sitting whether in your book or on your screen.

If instead of a printed textbook for one or more of your courses you are accessing digital content, you should find effective ways to do each step of actively reading the material. Chapters in digital textbooks are often “scrollable” by learning objectives and sections. In addition, quizzes and interactive exercises allow you to test your understanding of the material and to practice concepts. Get familiar with the tools and navigation functions available to get the most out of digital products.

Previewing will require some time up front, but it will save you time later. As you preview the text material, look for connections between the text and the related lecture material. Remember the related terms and concepts in your notes from the lecture. Use these strategies to warm up. Ask yourself: Why am I reading this? What do I want to know?

Keep in mind that different types of textbooks can require more or less time to read. For example, depending on your interests and previous knowledge, you might be able to read a psychology text more quickly than a biology text that includes many unfamiliar scientific words. If you experience difficulty in reading any of your textbooks, ask for help from your instructor, another student, or a tutor at the learning center.

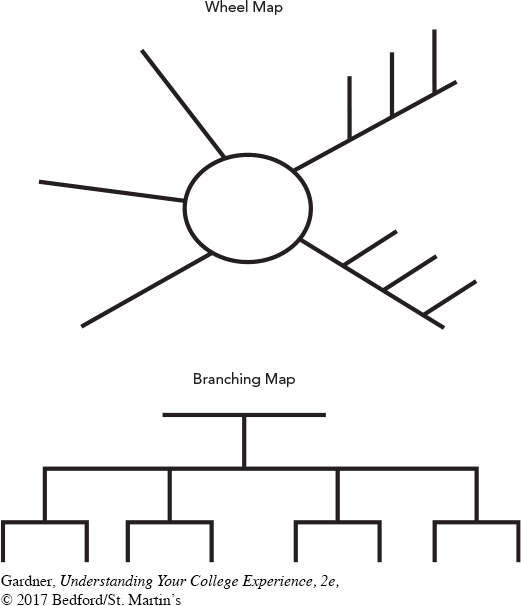

Mapping. Mapping is a preview strategy in which you draw a wheel or branching structure to show relationships between main ideas and secondary ideas and how different concepts and terms fit together; it also helps you make connections to what you already know about the subject (see Figure 6.1). Mapping the chapter as you preview it provides a visual guide for how different ideas in a chapter relate to each other. Because many students identify themselves as visual learners, visual mapping is an excellent learning tool not only for reading but also for test preparation.

In the wheel structure, place the central idea of the chapter in the circle. The central idea should be in the introduction to the chapter and might even be in the chapter title. Place secondary ideas on the lines connected to the circle, and place offshoots of those ideas on the lines attached to the main lines. In the branching map, the main idea goes at the top, followed by supporting ideas on the second tier, and so forth. Fill in the title first. Then, as you skim the chapter, use the headings and subheadings to fill in the key ideas.

YOUR TURN > TRY IT

Sketch either the wheel map or the branching map on a piece of notebook paper, and map this chapter.

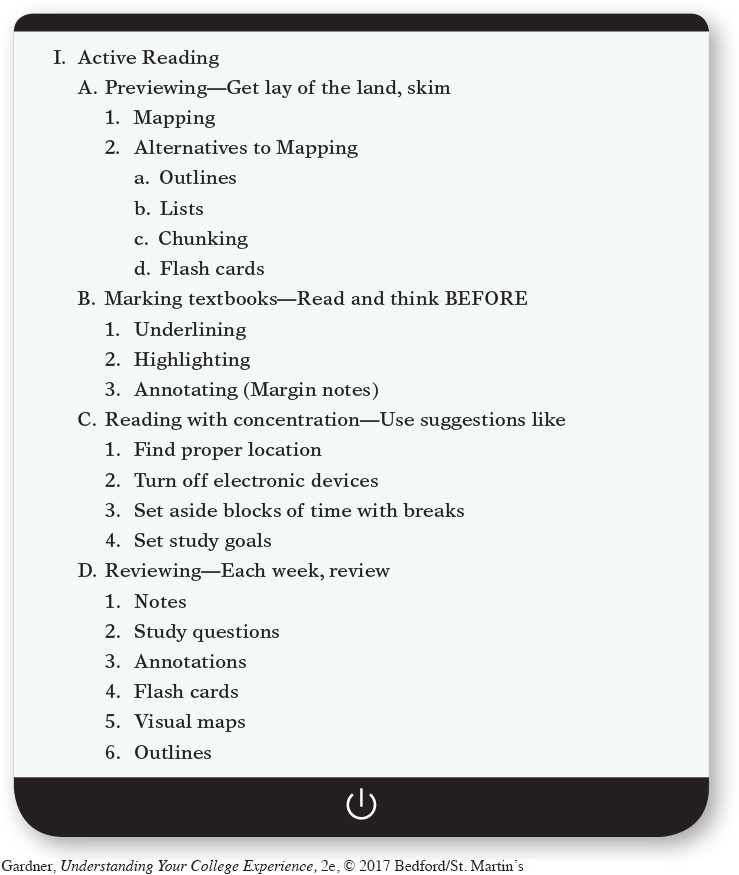

Outlining or Listing. Perhaps you are more of a read/write learner than a visual learner and prefer a more step-by-step visual image. If so, consider making an outline of the headings and subheadings in the chapter (see Figure 6.2, which shows an outline of the first section of this chapter). You can usually identify main topics, subtopics, and specific terms under each subtopic in your text by the size of the print. Notice, also, that the different levels of headings in a textbook look different. They are designed to show relationships among topics and subtopics covered within a section. Flip through this textbook to see how the headings are designed—look at the main headings and also the subheadings.

To save time when you are outlining, don’t write full sentences. Rather, include clear explanations of new technical terms and symbols. Pay special attention to topics that the instructor covered in class. If you aren’t sure whether your outlines contain too much or too little detail, compare them with the outlines your classmates or members of your study group have made. Check with your instructor during office hours. In preparing for a test, review your chapter outlines to see how everything fits together.

Another previewing technique is listing. A list can be effective when you are dealing with a textbook that introduces many new terms and their definitions. Set up the list with the terms in the left column, and fill in definitions, descriptions, and examples on the right as you read or reread. Divide the terms on your list into groups of five, seven, or nine, and leave white space between the clusters so that you can visualize each group in your mind. This practice is known as chunking. We learn material best when it is in chunks of five, seven, or nine.

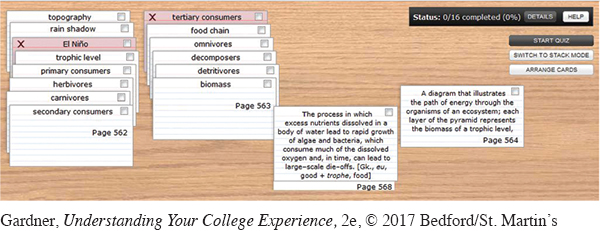

Creating Flash Cards. Flash cards are like portable test questions—you write a question or term on the front of a small card and the answer or definition on the back. Or in a course that requires you to memorize dates, like American history, you might write a key date on one side of the card and the event on the other. To study chemistry, you would write a chemical formula on one side and the ionic compound on the other. You might use flash cards to learn vocabulary words or practice simple sentences for a language course. Creating the cards from your readings and using them to prepare for exams are great ways to retain information and are especially helpful for visual and kinesthetic learners. Some apps, such as Chegg Flashcards or StudyBlue, enable you to create flash cards on your mobile devices (see Figure 6.3). If you are using digital course materials, it is likely that each chapter offers digital flash cards that you can click through. Often digital flash cards in college course materials give students the ability to sort the cards by front or back and to make virtual piles of the terms and concepts they need to practice and those they have mastered.

YOUR TURN > TRY IT

Prepare flash cards for the key terms that appear in this chapter. Bolded key terms are defined where they appear in the text.

Strategies for Reading and Marking Your Textbook

After completing your preview, you are ready to read the text actively. With your map, outline, list, or flash cards to guide you, mark the sections that are most important. To avoid marking too much or marking the wrong information, first read without using your pencil, highlighter, or any digital tools. This means you should read the text at least twice.

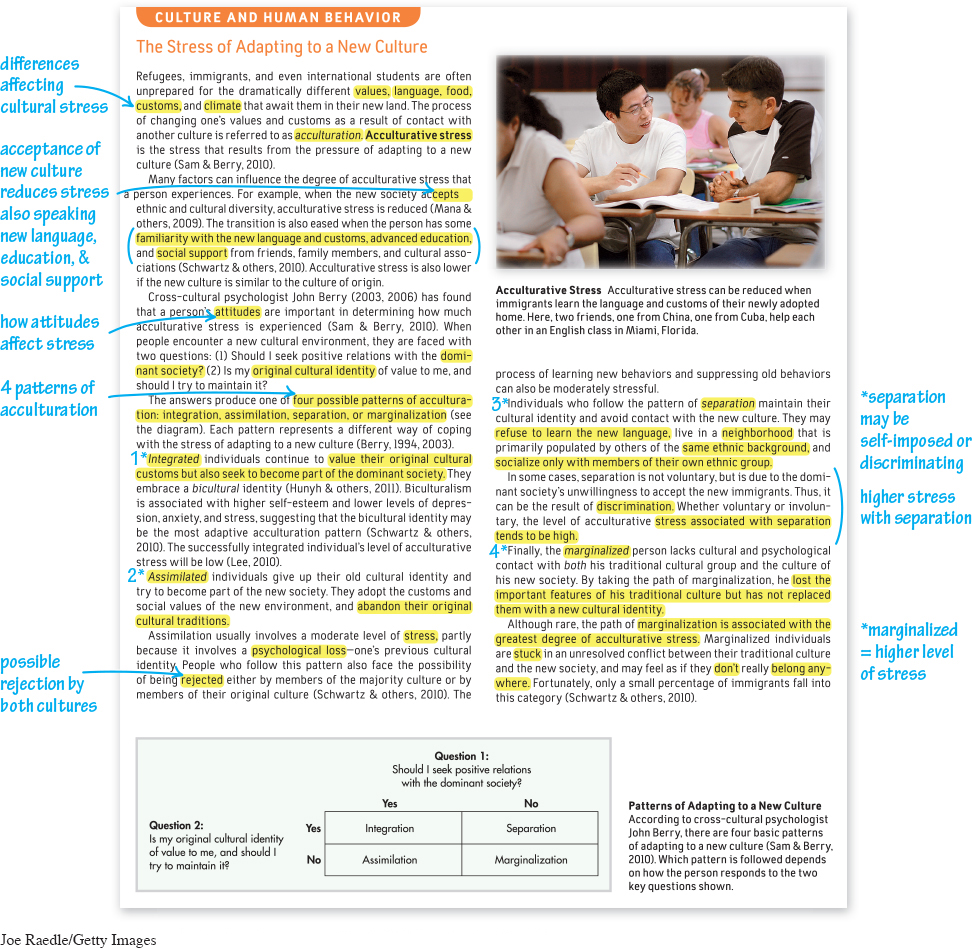

Marking is an active reading strategy that helps you focus and concentrate as you read. When you mark your textbook, you underline, highlight, or make margin notes or annotations—notes or remarks about a piece of writing—either on the book or digitally on your e-book pages. Figure 6.4 provides an example of each method. No matter what method you prefer, remember these important guidelines:

Read before you mark. Finish reading a section before you decide which are the most important ideas and concepts.

Think before you mark. When you read a text for the first time, everything can seem important. After you complete a section, reflect on it to identify the key ideas. Ask yourself: What are the most important ideas? What terms has the instructor emphasized in class? What will I see on the test? This can help you avoid marking too much material. On a practical note, if you find that you have made mistakes in how you have highlighted or that your textbooks were already highlighted by another student, select a completely different color highlighter to use. It is easier to correct highlighting mistakes on e-books by undoing them.

Highlight or underline purposefully. Highlights and underlines are intended to pull your eye only to key words and important facts. If highlighting or underlining is actually a form of procrastination for you (you are reading through the material but planning to learn it at a later date) or if you are highlighting or underlining nearly everything you read, you might be doing yourself more harm than good. You won’t be able to identify important concepts quickly if they’re lost in a sea of color or lines. Ask yourself whether your highlighting or underlining is helping you be more active in your learning process.

Take notes while you are marking. Rather than relying on marking alone, consider taking notes as you read. Just noting what’s most important doesn’t mean you learn the material, and it can give you a false sense of security. When you force yourself to put something in your own words while taking notes, you are not only predicting exam questions but also evaluating whether you can answer them. You can add your notes to the map, outline, list, or flash cards you created while you previewed the text or use the digital tools available for note taking on e-books. You can then review your notes from the reading with a friend or study group when preparing for tests and exams.

Although these active reading strategies take more time at the beginning, they save you time in the long run because they help you focus on the reading and make it easy to review.

Reading with Concentration

You might have trouble concentrating or understanding some content when you read textbooks. This is normal, and many factors contribute to this problem: the time of day, your energy level, your interest in the material, how you manage nearby distractions, the amount of sleep you have had in the past 24 hours, and your study location.

YOUR TURN > TRY IT

The next time you are reading a textbook, monitor your ability to concentrate. Check your watch when you begin, and check it again when your mind begins to wander. How many minutes did you concentrate on your reading? What can you do to keep your mind from wandering?

Consider these suggestions, and decide which would help you improve your reading ability:

Find a quiet study place. Choose a room or location away from traffic and distracting noises such as the campus information commons. Avoid studying in your bed because your body is conditioned to go to sleep there.

Mute or power off your electronic devices. Store your cell phone in your book bag or some other place where you aren’t tempted to check it. If you are reading on a device like a laptop or tablet, download what you need and disconnect from WiFi, so you’re not tempted to e-mail, chat, or check social media sites.

Read in blocks of time, with short breaks in between. Some students can read for 50 minutes; others find that a 50-minute reading period is too long. By reading for small blocks of time throughout the day instead of cramming in all your reading at the end of the day, you should be able to process material more easily.

Set goals for your study period. A realistic goal might be “I will read 20 pages of my psychology text in the next 50 minutes.” Reward yourself with a 10-minute break after each 50-minute study period.

Engage in physical activity during breaks. If you have trouble concentrating or staying awake, take a quick walk around the library or down the hall. Stretch or take some deep breaths, and think positively about your study goals. Then go back to studying.

Actively engage with the material. Write study questions in the margins, take notes, or recite key ideas. Reread confusing parts of the text, and make a note to ask your instructor for clarification.

Focus on the important portions of the text. Pay attention to the first and last sentences of paragraphs and to words in italics or bold type.

Understand the words. Use the glossary (a list of key words and their definitions) in the text or a dictionary to find definitions of unfamiliar terms.

Use organizers as you read. Keep the maps, outlines, lists, or flash cards you created during your preview as you read, and add to them as you go. For example, you can use Table 6.1 to organize information while you are reading:

| Date: | Course: |

| Textbook: | Chapter # and Title: |

| What is the overall idea of the reading? | |

|

What is the main idea of each major section of the reading? Section 1: Section 2: Section 3: |

|

|

What supporting ideas are presented in each section of the reading? Examples? Statistics? Any reference to research? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. |

|

| What are the key terms, and what do they mean? | |

| What are the conclusions from the reading? | |

|

What are two or three things I remember after reading? 1. 2. 3. |

|

Reviewing

The final step in active textbook reading is reviewing. Reviewing means looking through your assigned reading again. Many students expect to read through their text material once and be able to remember the ideas four, six, or even twelve weeks later at test time. More realistically, you will need to include regular reviews in your study process. Here is where your class notes, study questions, margin notes and annotations, flash cards, visual maps, or outlines will be most useful. Your study goal should be to review the material from each chapter every week. Here are some strategies for using your senses to review your reading:

Recite aloud.

Tick off each item on a list on your fingertips.

Post diagrams, maps, or outlines around your living space to see them often and visualize them while taking the test.