6.2 STRATEGIES FOR READING TEXTBOOKS

As you begin reading, be sure to learn more about the textbook and its author by reading sections at the beginning of the book, such as the preface, foreword, introduction, and author’s biographical sketch. The preface, a brief overview usually at the beginning of a book, is typically written by the author (or authors) and tells you why they wrote the book and what material the book covers; it also explains the book’s organization and give insight into the author’s viewpoint—all of which will likely help you see the relationships among the facts presented and comprehend the ideas presented across the book. Reading the preface can come in handy if you are feeling a little lost at different points in the term. The preface often lays out the tools available in each chapter to guide you through the content, so if you find yourself struggling with the reading, be sure you are taking advantage of these tools.

The foreword is often an endorsement of the book written by someone other than the author. Some books have an additional introduction that reviews the book’s overall organization and its contents, often chapter by chapter. Some textbooks include study questions at the end of each chapter. Take time to read and respond to these questions, whether or not your instructor requires you to do so.

YOUR TURN > DISCUSS IT

How do you usually read a textbook chapter? Do you just read it? Do you highlight or take notes as you go?

Textbooks Are Not Created Equal

Textbooks in the major disciplines—areas of academic study—are different in their organizations and styles of writing. Some may be easier to understand than others, but don’t give up if the reading level is challenging.

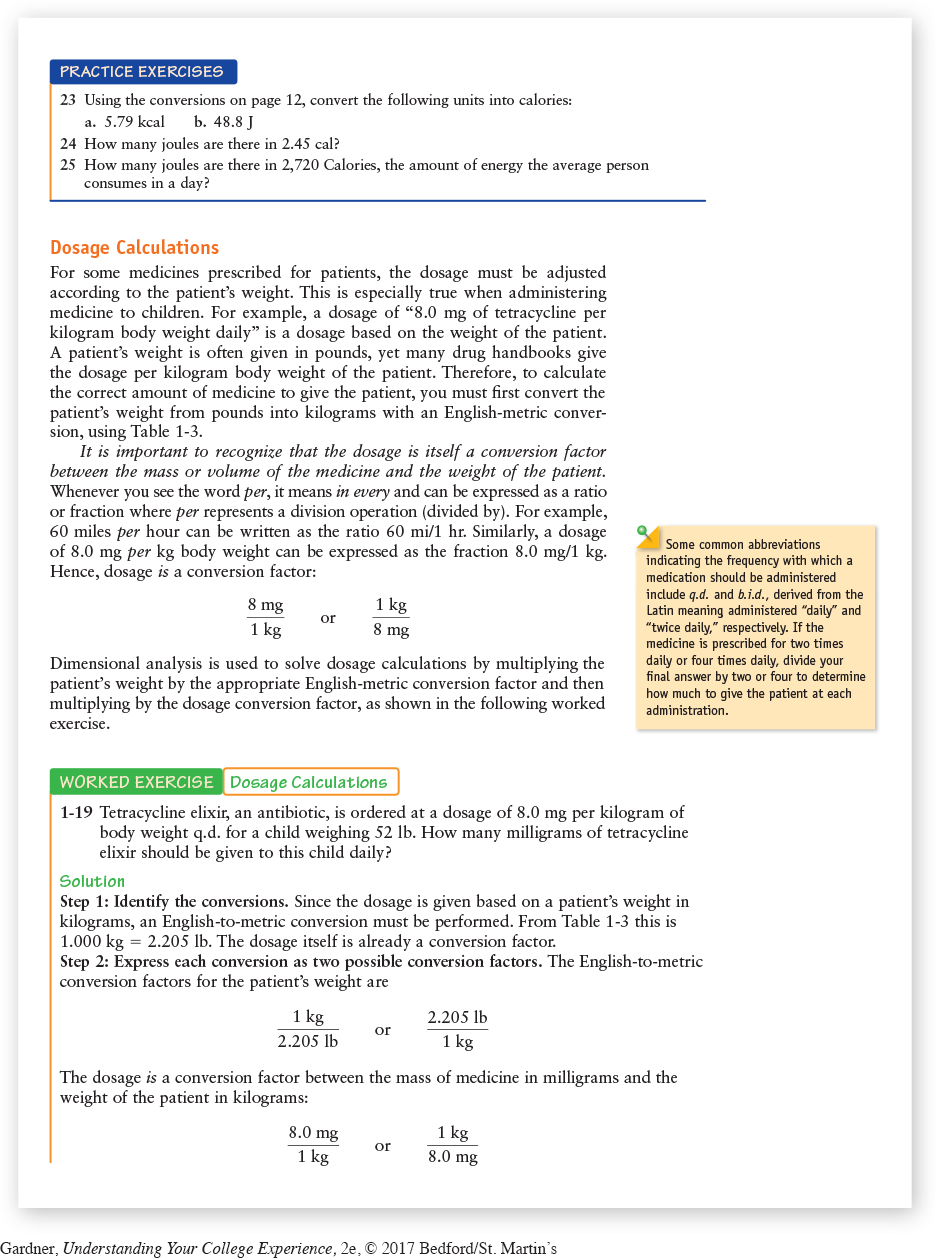

Math and science texts are filled with graphs and figures that you will need to understand in order to grasp the content and the classroom presentations. They are also likely to have less text and more practice exercises than other textbooks do. If you have trouble reading and understanding any of your textbooks, get help from your instructor or your college’s learning center.

Textbooks must try to cover a lot of material in a limited space, and they do not necessarily provide all the things you want to know about a topic. If you find yourself interested in a particular topic, go to the primary sources—the original research or documents on a topic. You’ll find those referenced in almost all textbooks, either at the end of the chapters or in the back of the book.

You might also go to other related sources that make the text more interesting and easier to understand. Your instructors might use the textbook only to supplement the lectures. Some instructors expect you to read the textbook carefully while others are much more concerned that you can understand broad concepts that come primarily from lectures. If your instructor hasn’t made it very clear how the text will be used, then you should ask the instructor for clarification. Ask your instructors what parts of the text the tests will cover and what types of questions will be used. It is also very important to ask if the tests will be cumulative, meaning going all the way back to the beginning of the course or just covering the material since the previous test.

Finally, not all textbooks are written in the same way. Some are better designed and written than others. If your textbook seems disorganized or hard to understand, let your instructor know your opinion; other students in your class may feel the same way. You could be helping future students by encouraging the instructor to change books! Your instructor might spend some class time explaining the text, its structure, and how it will be used in the course, and he or she can meet with you during office hours to help you with the material.

Math Texts

While the previous suggestions about textbook reading apply across the board, mathematics textbooks present some special challenges because they usually have lots of symbols and few words. Each statement and every line in the solution of a problem needs to be considered and processed slowly. Typically, the author presents the material through definitions, theorems, and sample problems. As you read, pay special attention to definitions. Learning all the terms that relate to a new topic is the first step toward understanding.

Math texts usually include derivations of formulas and proofs of theorems. You must understand and be able to apply the formulas and theorems, but unless your course has a particularly theoretical emphasis, you are less likely to be responsible for all the proofs. So if you get lost in the proof of a theorem, go on to the next item in the section. When you come to a sample problem, it’s time to get busy. Pick up pencil and paper, and work through the problem in the book. Then cover the solution and think through the problem on your own.

Of course, the exercises in each section are the most important part of any math textbook. A large portion of the time you devote to the course will be spent completing assigned exercises. It is absolutely necessary to do this homework before the next class, whether or not your instructor collects it. Success in mathematics requires regular practice, and students who keep up with math homework, either alone or in groups, perform better than students who don’t, particularly when they include in their study groups other students who are more advanced in math.

After you complete the assignment, skim through the other exercises in the problem set. Reading the unassigned problems will help you understand more about the topic. Finally, talk the material through to yourself, and be sure your focus is on understanding the problem and its solution, not on memorization. Memorizing something might help you remember how to work through one problem, but it does not help you learn the steps involved so that you can use them for solving other similar problems.

YOUR TURN > DISCUSS IT

Discuss with classmates two or three of your challenges in learning from your math textbooks. Share some strategies that you use to study math.

Science Texts

Your approach to your science textbook will depend somewhat on whether you are studying a math-based science, such as physics, or a text-based science, such as biology. In either case, you need to become familiar with the overall format of the book. Review the table of contents and the glossary, and check the material in the appendixes (supplemental materials at the end of the book). There you will find lists of physical constants, unit conversions, and various charts and tables. Many physics and chemistry books also include a mini-review of the math you will need in science courses (see Figure 6.5).

Notice the organization of each chapter, and pay special attention to graphs, charts, and boxes. The amount of technical detail might seem overwhelming. Remember that most textbook authors take great care in presenting material in a logical format, and they include tools to guide you through the material. Learning objectives at the start and summaries at the end of each chapter can be useful to study both before and after reading the chapter. You will usually find answers to selected problems in the back of the book. Use the answer key or the student solutions manual to increase your understanding of the chapters.

As you begin an assigned section in a science text, skim the material quickly to gain a general idea of the topic and to begin becoming familiar with the new vocabulary and technical symbols. Then look over the end-of-chapter problems so that you’ll know what to look for in your detailed reading of the chapter. State a specific purpose: “I’m going to learn about recent developments in plate tectonics,” or “I’m going to distinguish between mitosis and meiosis,” or “Tonight I’m going to focus on the topics in this chapter that were stressed in class.”

Should you underline and highlight, or should you outline the material in your science textbooks? You might decide to underline or highlight for a subject such as anatomy, which involves a lot of memorization. In most sciences, however, it is best to outline the text chapters.

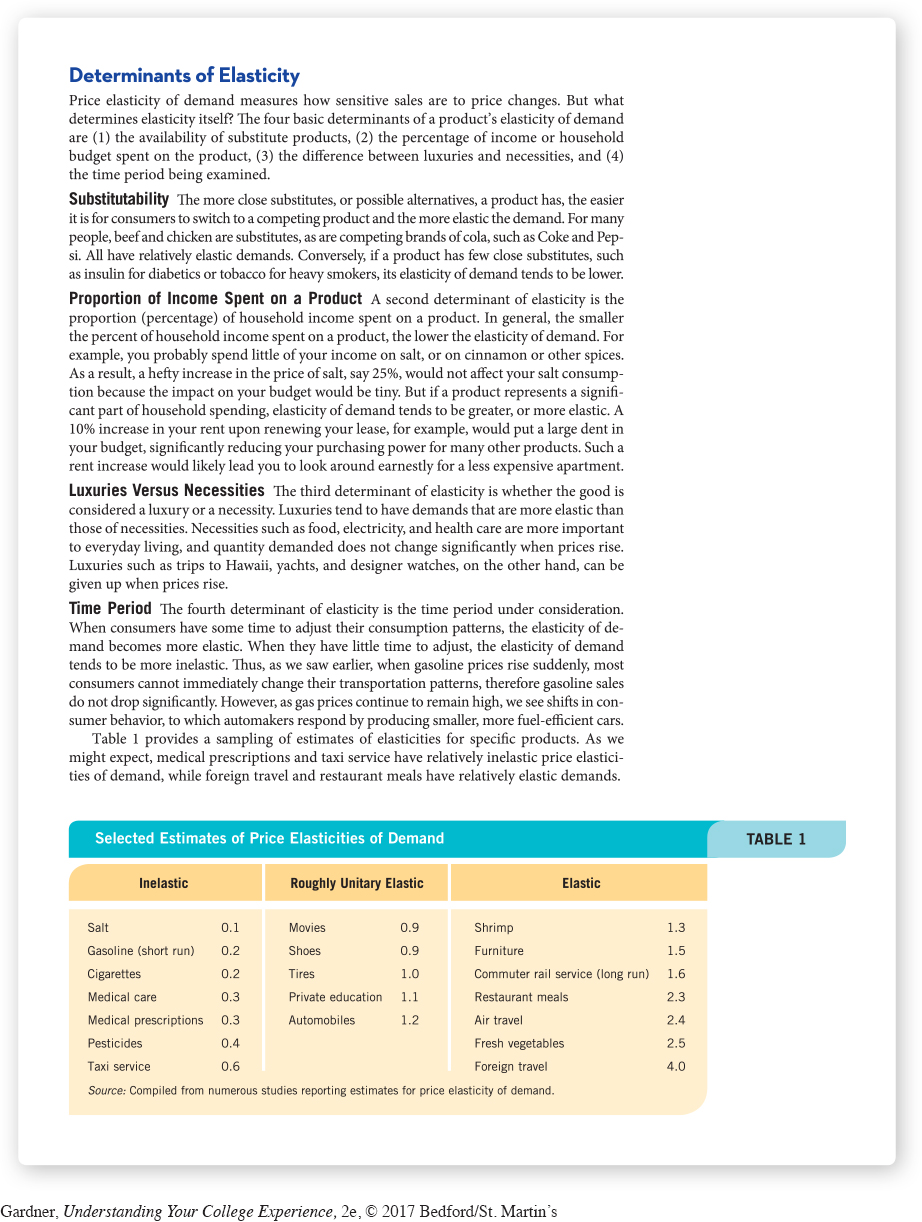

Social Science and Humanities Texts

Many of the suggestions that apply to science textbooks also apply to reading in the social sciences (academic disciplines that examine human aspects of the world, such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, economics, political science, and history). Social science textbooks are filled with terms specific to the particular field of study (see Figure 6.6). These texts also describe research and theory building and contain references to many primary sources. Your social science texts might also describe differences in opinions or perspectives. Social scientists do not all agree on any one issue, and you might be introduced to a number of ongoing debates about particular issues. In fact, your reading can become more interesting if you seek out different opinions about the same issue. You might have to go beyond your course textbook, but your library will be a good source of various viewpoints about ongoing controversies.

Textbooks in the humanities (branches of knowledge that investigate human beings, their culture, and their self-expression, such as philosophy, religion, literature, music, and art) provide facts, examples, opinions, and original material such as stories or essays. You will often be asked to react to your reading by identifying central themes or characters.

YOUR TURN > WORK TOGETHER

In a small group, discuss how important you think textbooks are in your courses in terms of what the instructor expects you to learn and master. What are some other ways to access the information you want and need in order to learn?

Supplementary Material

Whether your instructor requires you to read material in addition to the textbook, you will learn more about the topic if you go to some of the primary and supplementary sources that are referenced in each chapter of your text. These sources can be journal articles, research papers, or original essays, and they can be found online or in your library. Reading the original source material will give you more detail than most textbooks do.

Many of these sources were originally written for other instructors or researchers. Therefore, they often refer to concepts that are familiar to other scholars but not necessarily to first-year college students. If you are reading a journal article that describes a theory or research study, one technique for easier understanding is to read from the end to the beginning. That is, first read the article’s conclusion and discussion sections. Then go back to see how the author performed the experiment or formed the ideas. In almost all scholarly journals, articles are introduced by an abstract, a paragraph-length summary of the methods and major findings. Reading the abstract is a quick way to get the main points of a research article before you start reading it. As you’re reading research articles, always ask yourself: So what? Was the research important to what we know about the topic, or, in your opinion, was it unnecessary?