7.2 HOW MEMORY WORKS

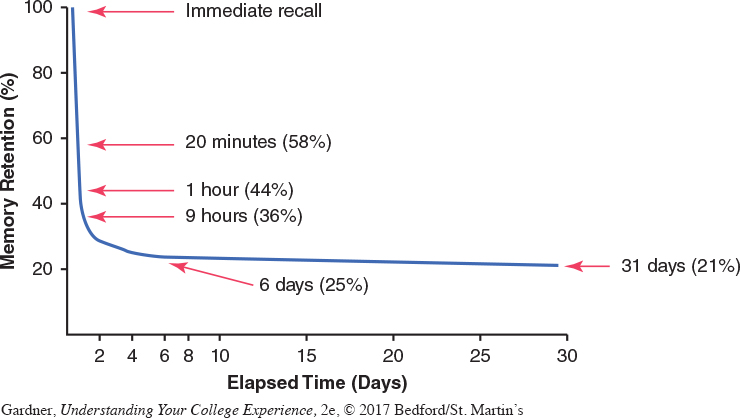

Learning experts describe two different processes involved in memory. The first is short-term memory, which involves retaining information, such as words or numbers, for about 15 to 30 seconds. After that you will forget the information stored in your short-term memory unless you take action to either keep that information in short-term memory or move it to long-term memory. Figure 7.2 shows that after nine hours, we remember less than 40 percent of the information!

Although short-term memory is limited, it has a number of uses. It serves as an immediate holding tank for information, some of which you might not need for long. It helps you maintain your attention span so that you can keep track of topics mentioned in conversation, and it enables you to focus on the goals you have at any moment. But even these simple functions of short-term memory fail on occasion. If you’re interrupted in any way, by a ringing phone or someone asking a question, you might find that your attention suffers and that you have to start over in reconstructing the contents of your short-term memory.

Long-term memory, the capacity to retain and recall information over the long term (from hours to years), is important to college success and can be divided into three categories:

Procedural memory deals with knowing how to do something, such as solving a mathematical problem or driving a car. You are using your procedural memory when you ride a bicycle, even if you haven’t ridden in years; when you cook a meal that you know how to prepare without using a recipe; or when you send a text.

Semantic memory involves facts and meanings without regard to where and when you learned those things. Your semantic memory is used when you remember word meanings or important dates, such as your mother’s birthday.

Episodic memory deals with particular events, their time, and their place. You are using episodic memory when you remember events in your life—a vacation, your first day of school, the moment your child was born. Some people can recall not only the event, but also the very time and place the event happened. For others, although the event stands out, the time and place are harder to remember.

Table 7.1 recaps the differences between short- and long-term memory.

| Short-Term Memory | Long-Term Memory |

| Stores information for about 15 to 30 secondsCan handle from five to nine chunks of information at one timeInformation either forgotten or moved to long-term memory |

Stores information for hours to yearsCan be described in three ways:

|

Connecting Memory to Deep Learning

Multitasking has become a fact of life for many of us, and many students believe that their use of multitasking makes them more efficient and productive. They even believe that multitasking is a necessity. However, this is not the case. Research summarized on the American Psychological Association website1 shows that trying to do several tasks at once can make it harder to remember the most important things. It is difficult to focus on anything for long if your life is full of daily distractions and competing responsibilities—school, work, commuting, and family responsibilities such as caring for children or parents—or if you’re not getting the sleep you need. Have you ever had the experience of walking into a room with a specific task in mind and immediately forgetting what that task was? You were probably interrupted either by your own thoughts or by someone or something else. Or have you ever felt the panic that comes when your mind goes blank during a test, even though you studied hard and knew the material? If you spent all night studying or partying, lack of sleep may have raised your stress level, causing you to forget what you worked hard to learn. Such experiences happen to most people at one time or another.

To do well in college and in life, it’s important that you improve your ability to remember what you read, hear, and experience. Concentration is a key element of learning and is so deeply connected to memory that you can’t really have one without the other.

The benefits of having a good memory are obvious. In college, your memory will help you retain information and earn excellent grades on tests. After college, at work, and in life in general, the ability to remember important details—names, dates, appointments—will save you energy and time and will prevent a lot of embarrassment.

Most memory strategies tend to focus on helping you remember bits and pieces of knowledge: names, dates, numbers, vocabulary words, formulas, and so on. However, if you know the date the Civil War began and the name of the fort where the first shots were fired but you don’t know why the Civil War was fought or how it affected history, you’re missing the point of a college education. College is a time to develop deep learning, understanding the why and how behind the details. So while remembering specific facts is necessary to do well in college and in your career, you will need to understand major themes and ideas. You will also need to improve your ability to think deeply about what you’re learning.

Myths about Memory

To understand how to improve your memory, let’s first look at what we know about how memory works. Although scientists keep learning new things about how our brains function, author Kenneth L. Higbee2 identifies some myths about memory (some you might have heard, and even believe). Table 7.2 lists four of these memory myths and what experts say about them:

| Myth | Reality |

| Some people have bad memories. | Although the memory ability you are born with is different from that of others, nearly everyone can improve his or her ability to remember and recall. Improving your concentration would certainly benefit your ability to remember! |

| Some people have photographic memories. | Some individuals have truly exceptional memories, but these abilities result more often from learned strategies, interest, and practice than from the natural ability to remember. |

| Memory benefits from long hours of practice. | Experts believe that practice often improves memory, but they argue that the way you practice is more important than how long you practice. For all practical purposes, the storage capacity of your memory is unlimited. In fact, the more you learn about a particular topic, the easier it is to learn even more. |

| People use only 10 percent of their brain power. | No one knows exactly how much of our brain we actually use. However, most researchers believe that we all have far more mental ability than we actively use. |