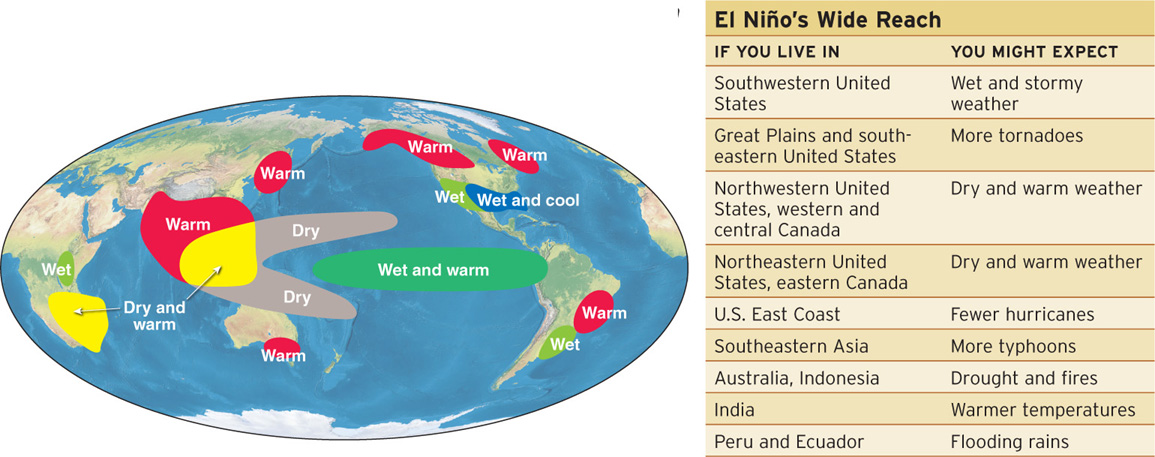

5.5 El Niño’s Wide Reach

Discuss how El Niño forms and describe its global effects.

For generations, fisherman in Peru have reaped the bounty of the sea. Commonly around Christmastime, their catches decrease as cold, nutrient-

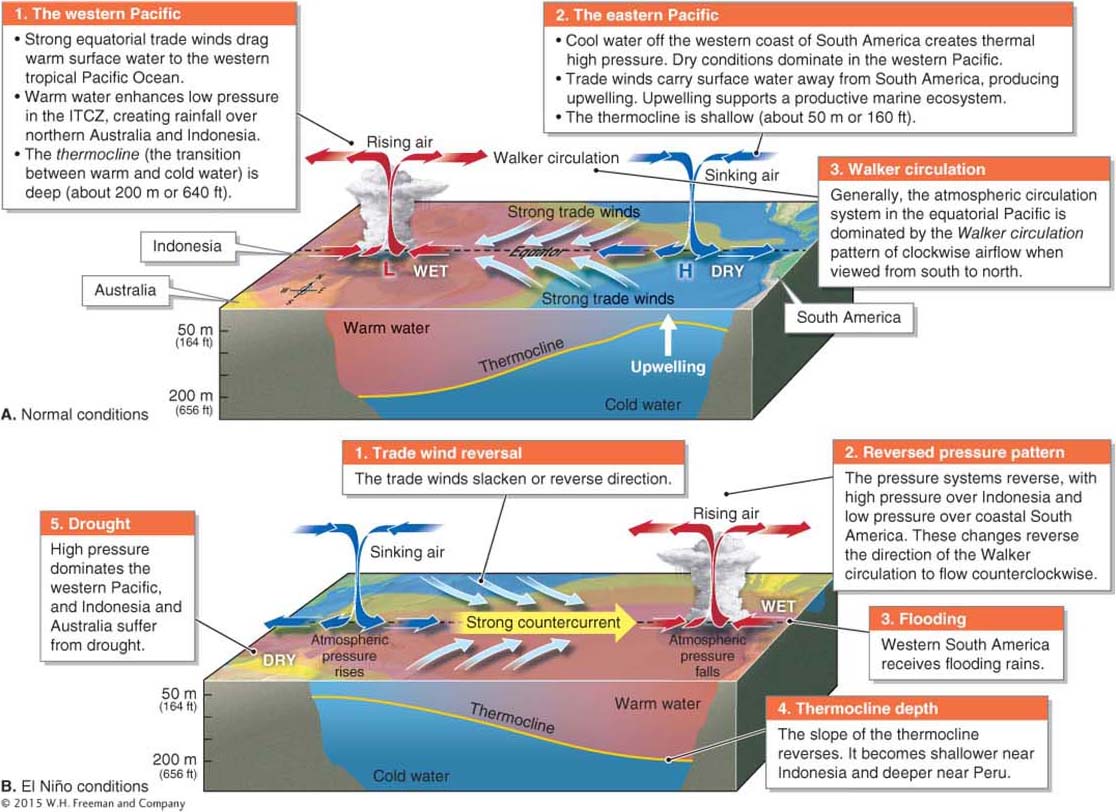

El Niño is not a storm system. It is a periodic shift in the state of Earth’s climate caused by the temporary slackening and reversing of the Pacific equatorial trade winds and increased surface temperatures in the seas off coastal Peru. Normally, El Niño lasts only a few weeks and does not go beyond the coast of western South America. During some El Niños, however, the cold waters do not immediately return. Instead, the warm surface water persists and gets warmer. This warm water affects climates around the world within a few months, creating a global El Niño event that can influence all the storm systems discussed thus far in this chapter.

El Niño

A periodic change in the state of Earth’s climate caused by the slackening and temporary reversal of the Pacific equatorial trade winds and increased sea surface temperatures off coastal Peru.

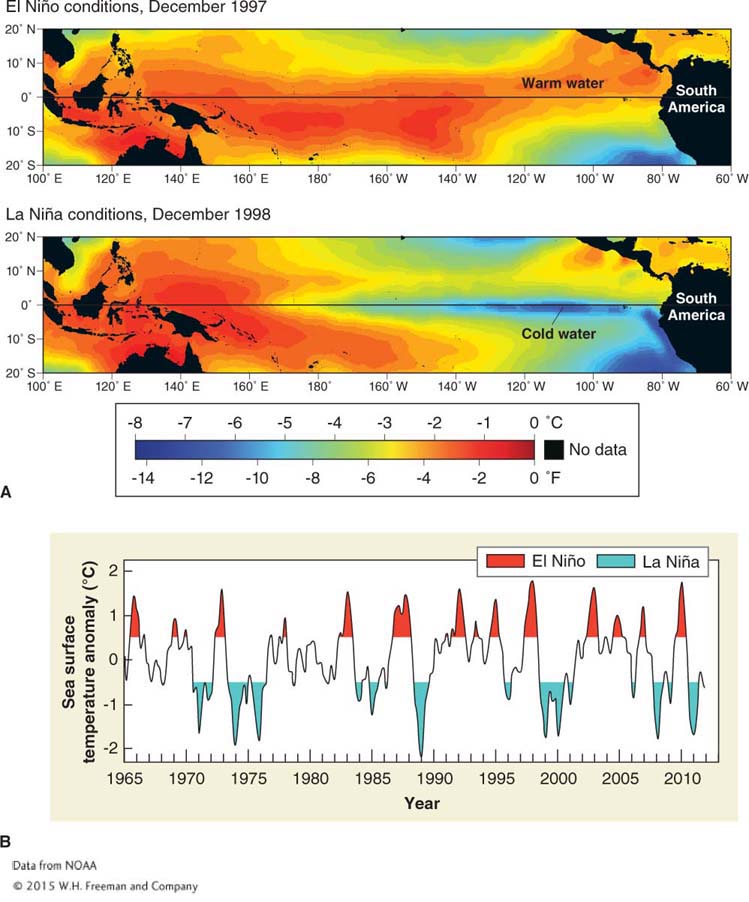

El Niño events occur randomly, about every 3 to 7 years on average. They develop in March through June and reach peak intensity between December and April, when equatorial sea surface temperatures are highest. By July, they usually dissipate, although some weak El Niños have lasted as long as four years.

El Niño’s Global Influence

The global influence of El Niño events illustrates the connections among the oceans, the atmosphere, and climate patterns around the world. For instance, during El Niño years, hurricane activity usually decreases in the Atlantic Ocean and increases in the Pacific Ocean. Tornadoes in North America increase. The Asian monsoon often weakens, resulting in dangerous drought and potential food shortages for millions. El Niño alters air temperature and precipitation patterns worldwide, usually in the pattern shown in Figure 5.25.

El Niño Development

Figure 5.26 shows the typical sequence of events in the tropical Pacific Ocean that lead up to an El Niño event. Slackening and reversal of the trade winds in the Pacific is one of the most prominent changes that lead up to an El Niño event.

Toward the end of an El Niño event, the pattern of atmospheric pressure returns to normal. After some El Niño events, the pressure pattern returns to an “enhanced normal,” a phenomenon called La Niña. During La Niña, the low pressure over Indonesia is deeper than normal and the high pressure near western South America is higher than normal. La Niña does not always follow El Niño, but when it does occur, it typically lasts about 9 months to a year.

El Niño and La Niña events and the changes they cause in the climate system are collectively referred to as ENSO (the El Niño-

Scientists still do not know what triggers El Niño, and they cannot reliably predict El Niño events more than 6 months in advance. During the last 50 years, El Niños and La Niñas occurred about half of the time (in a total of about 25 years). The other half of the time, ocean conditions were near normal. Given how often these patterns develop, many scientists question whether “normal” conditions are simply transitional states and the ENSO system is normal. Furthermore, recent research on corals indicates that El Niño intensity has been greater in the last several decades than at any other time in the last 7,000 years, and perhaps much longer. These data are leading scientists to question the potential influence of anthropogenic climate change on El Niño.