8.5 The Value of Nature

Assess the connection between the well-

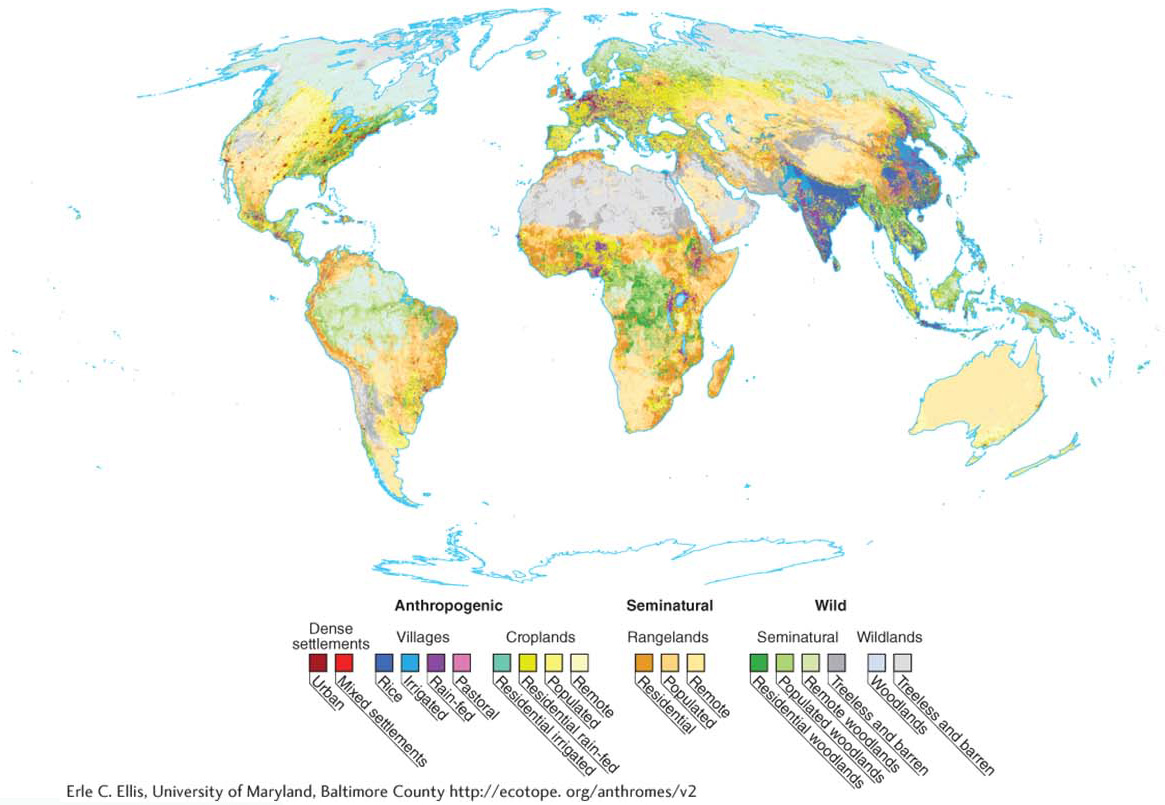

Human modification of the environment is one of the prevailing themes in our tour of biomes. All biomes have been modified by people, some more than others. The concept of natural biomes, as described in this chapter, provides a background for the current mosaic of human land uses, as shown in Figure 8.28.

Habitat fragmentation is the division and reduction of natural habitat into smaller pieces by human activity. In his book Song of the Dodo, David Quammen compares the process of habitat fragmentation to cutting up a Persian rug: A whole Persian rug functions exquisitely, but if the rug is cut into pieces, it becomes worthless. Our tour of biomes has revealed that habitat fragmentation is reducing Earth’s natural biomes and ecosystems into ever-

habitat fragmentation

The division and reduction of natural habitat into smaller pieces by human activity.

India, Java, and much of eastern China are bright blue and purple in Figure 8.28, indicating villages with large human populations engaged in irrigated and rain-

Food production accounts for a large proportion of human land use. The most widespread human land use is rangelands, where domesticated livestock graze. Rangelands are followed by croplands, the second most widespread human land use.

Habitat and Species Loss

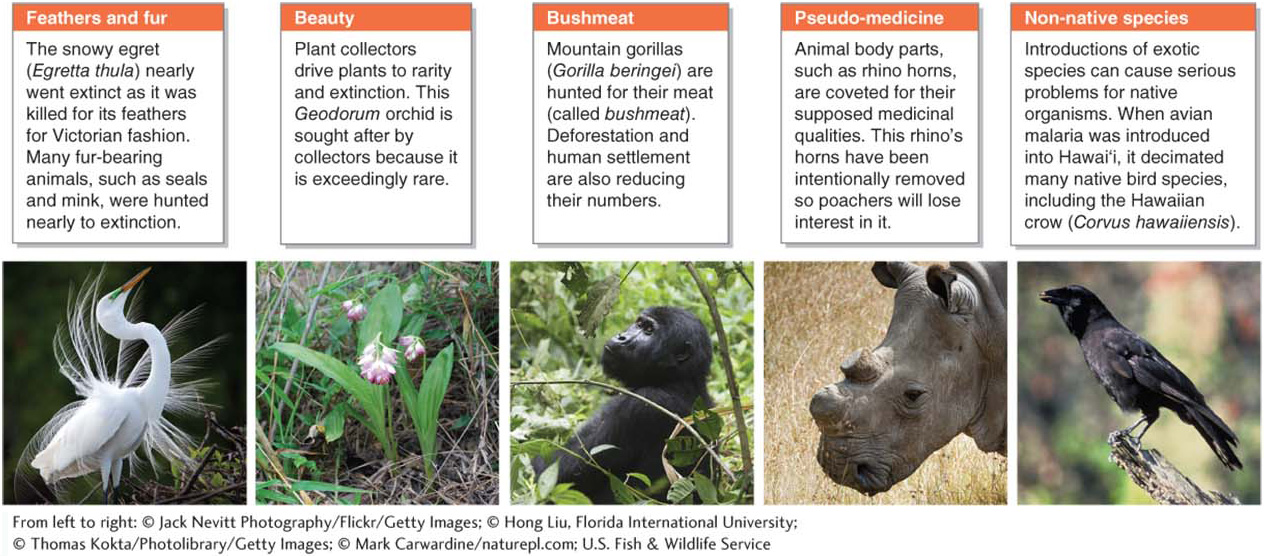

Over the last 500 years, hunting pressure was responsible for over 90% of the extinctions of mammals and birds. Today, habitat fragmentation, climate change, and competition from non-

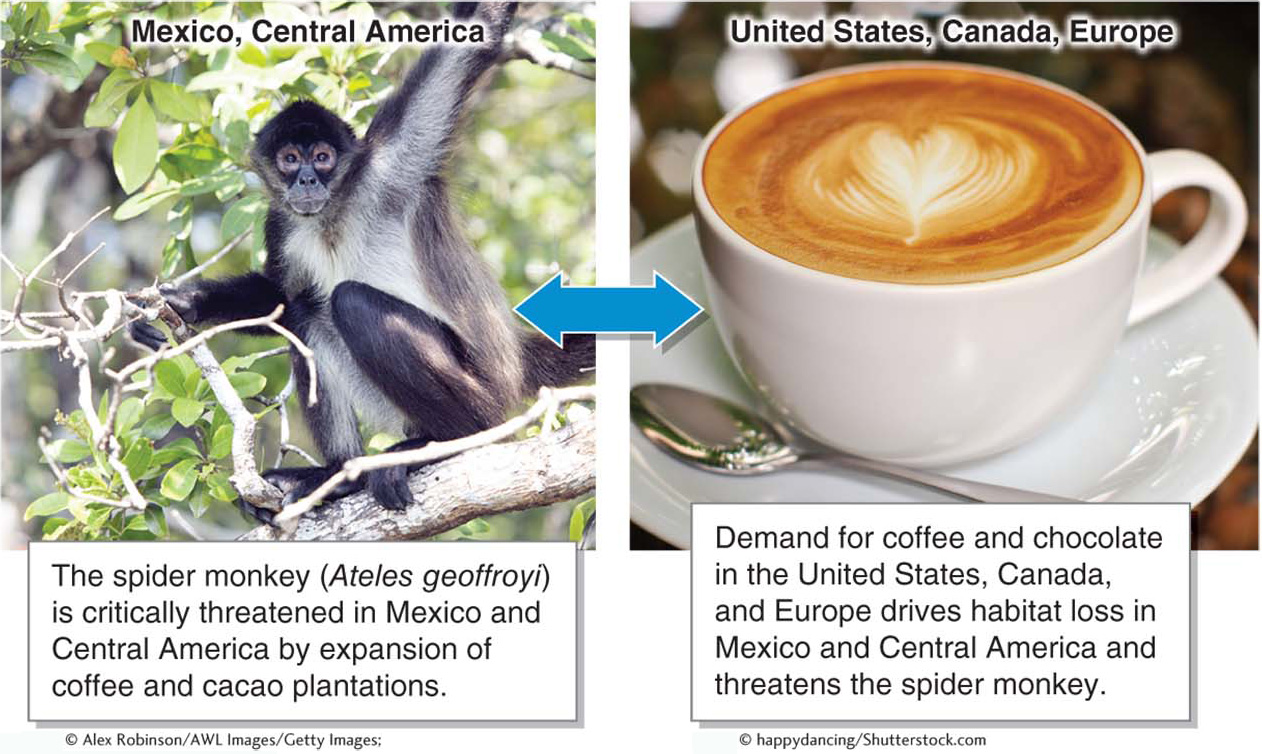

Most of us do not hunt rhinos for their horns or orchids for our collections. But we all contribute to species loss through habitat fragmentation. The materials people use and the foods people eat come to us through a global network of trade. International trade, driven by consumer demand, accounts for 30% of the threats to species worldwide. Research published in the journal Nature in June 2012 details the relationships between international demand for goods and threats to species resulting from those demands. Many of the goods and materials North Americans and Europeans enjoy originate overseas, where their extraction or production takes an environmental toll. Coffee, for example, comes from Brazil, beef from Argentina, cacao (chocolate) from Central America, and palm oil from Indonesia. Figure 8.30 links these goods to the ecosystems from which they come.

The Value of Natural Biomes

Why should anyone care about the loss of a rare orchid, or a spider monkey in Central America? It is unfortunate that 21,000 km2 (8,100 mi2) of Amazon rainforest are lost each year, and with it, probably several thousand species never before seen by people. But does it matter in a practical sense? Most people will never see a tropical rainforest. Fewer still will ever see a spider monkey outside a zoo.

Trade in coffee and chocolate is thriving. Is that not good? People matter, too. Why should we value orchids and spider monkeys? In a strictly self-

Material resources: Think about the materials around you right now—

the table, your phone, this book, your clothes and food, the materials in the building you are in. All of these materials, without exception, were at one point resources found in nature. Humans depend on nature for raw resources. When we degrade ecosystems we reduce their natural resources. Ecosystem services: Natural ecosystems and the species in them provide humans with clean air and drinking water, fertile soil, filtration of pollutants along coastal zones, buffers against hurricane storm surges, pollination of food crops, and potential new compounds for medicines. These benefits can all be viewed as services because people need them for their health and sustenance.

Aesthetic delight: Without vibrant and healthy nature, the world would be gritty, boring, and monotonous. Ecosystems and their species do more than clean the air and water and fill our stomachs—

they feed our spirits. Without the complete Persian rug of life, the world is less interesting and nurturing for people. Ecotourism revenue: Although not without controversy, ecotourism provides important revenue sources for many regions. People travel long distances to see wild places, and in so doing, they create a significant revenue source for people in the places they visit.

Climate stabilization: Saving species forestalls climate change. Saving the orangutan, for instance, requires saving the forests in which these animals live. Healthy forests absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and slow the rate at which this greenhouse gas warms the planet (see Chapter 6). Deforestation releases the carbon stored in trees and the soil to the atmosphere.

Humans are connected to and supported by the biosphere. Saving species and their habitats maintains natural resources, preserves ecosystem services, generates revenue through ecotourism, and preserves a richer and more interesting world. Saving species also addresses the problem of climate change. So the answer to the question, “Do people matter?” is resoundingly yes. The health and well-