GT.5 The Scientific Method and Easter Island

Apply the scientific method to Easter Island to study its history of human settlement.

Most people are drawn by the beauty of nature and are curious about what it is and how it works. Scientists are no exception. In most cases, scientists are driven by their interest in the world. Scientists follow the scientific method to answer questions about the world in a way that is based on rational thought and repeatable observations and conclusions. The scientific method loosely follows this sequence:

Observations: You observe something that interests you or that you do not fully understand. Your observations must be repeatable; that is, others must be able to observe the same phenomenon.

Questions: You might ask why a thing is present or absent, why it behaves the way it does, how old it is, or where it came from.

Develop a hypothesis: The information you collect stimulates a hypothesis, which is a well-

thought- out, testable idea that poses an answer to your original question. Hypotheses can be developed before, during, or after data collection. Collect data: You collect data (often in the form of measurements) to learn more or to test your hypothesis.

Test the hypothesis: Scientific hypotheses must be testable. For example, a hypothesis about a tree’s age is testable by counting the number of annual rings in the tree’s trunk, but a hypothesis about whether a tree feels pain is not testable. Your hypothesis may be supported by all available information. However, the information you gathered may not support your hypothesis. In that case, you must either modify your hypothesis or throw it out and develop a new one.

Further inquiry: Whether your original hypothesis was supported by the data or not, new information and new questions often lead to new ideas and further inquiry.

Easter Island: The Scientific Method Applied

Exploring the unusual history of Easter Island illustrates the sequence of observations, ideas, hypotheses, data collection, and hypothesis testing in the scientific method.

1. Observation: Stone Statues

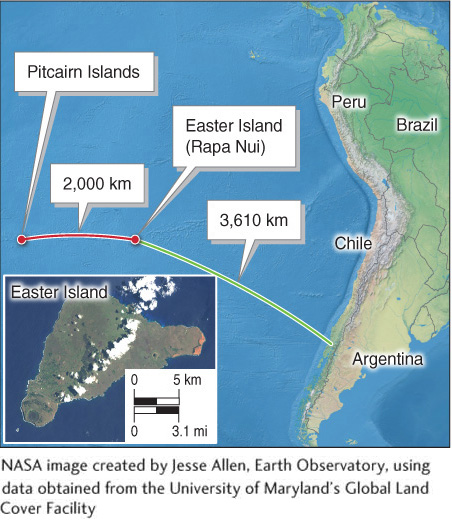

Easter Island is a small, 166 km2 (64 mi2) volcanic island in the South Pacific Ocean. A person can walk around the entire island in half a day. The closest human neighbors are about 2,000 km (1,240 mi) to the west in the Pitcairn Islands (Figure GT.31).

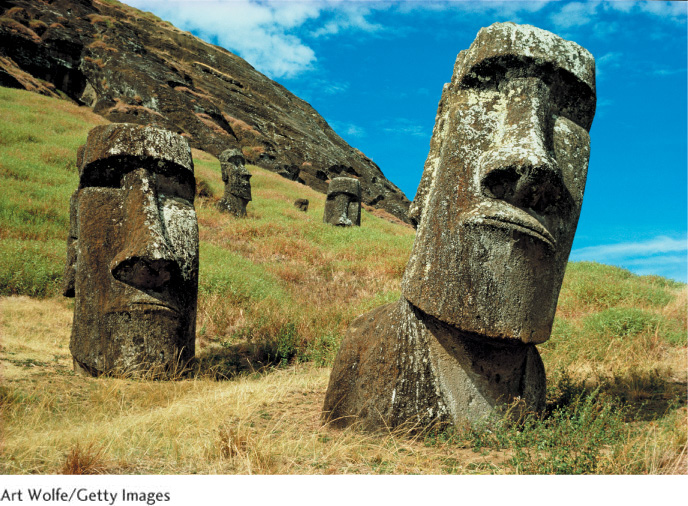

On Easter, 1722, the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen was the first European to visit Easter Island. Roggeveen found a small population of people who had no boats and no wood, and who were locked in state of warfare. The hundreds of large stone statues on the island, called moai, perplexed him (Figure GT.32).

When asked, islanders said the statues “walked” to their present locations. They did not know how the statues were moved to their current positions from the stone quarries where they were carved, which are located far away from where the statues stand on the island today. Roggeveen never solved the mystery.

2. Question: How Were the Statues Moved across the Island?

Question 901.16

Who built the massive statues on Easter Island and how?

Evidence indicates that Easter Islanders began building the large statues over 1,000 years ago and may have transported them across the island using a system of ropes and log rollers.

A person could claim the statues were once alive and walked to their present positions. This claim is not a scientific hypothesis, however, because it is easy to declare false—

3. Collect Data: Pollen

Without data, scientific inquiry is impossible. In 1977, British geographer J. R. Flenley was one of the first scientists to study the ecological history of Easter Island. His research team took cores of sediments from the marshes on the island and analyzed the pollen in the cores. Pollen from plants had been trapped in the marshes and preserved. The upper layers of the marshes reflect modern vegetation. The deeper sediments come from further back in time and contain ancient pollen from long ago. Changes in pollen types through time reveal the island’s dynamic ecological history.

When Jacob Roggeveen reached the island, it was grassy and windswept, with almost no trees, as it largely is today. Flenley and his colleagues suspected that conditions were different in the past. As they analyzed the pollen data, they found, much to their amazement, that the island was once covered with some 23 species of trees. They also saw a decline in tree pollen that began around 800 CE. By 1550, very little tree pollen was preserved in the sediments, indicating that Easter Island’s forests were gone by that time.

4. Hypothesis: Log Rollers

Hypotheses are testable ideas. They are statements that can be refuted. The pollen data provided enough information for researchers to develop a hypothesis about the transportation of the stone figures. Having discovered that the islands were once heavily forested, the scientists concluded that the statues were transported across the island using trees somehow. This conclusion led to a new hypothesis: Extensive track and roller systems made out of tree logs were used to move the statues.

5. Test the Hypothesis: Log Rollers Do Work

Is it possible to move the massive statues using logs as rollers? To test this idea, researchers later returned to Easter Island and attempted to move the statues using only those materials that would have been available to the original inhabitants. Although their efforts gave mixed results, they were able to move and right a statue after much labor using this technique. Other techniques using timber and twine made from trees met with mixed success.

A recent technique of “walking” the statues by lassoing them around the head with ropes and carefully balancing and rocking them back and forth to move them has also been tried with success on a 4.5-

6. Further Inquiry: Collapse of Society

One of the hallmarks of the scientific process is that scientists follow the data to an outcome, rather than having an outcome in mind first and seeking support for it. There is no place for personal bias or desires in the scientific process. The researcher follows the data wherever they lead, as long as the data are legitimate and are analyzed logically and rationally.

Scientists studying Easter Island examined the preserved garbage mounds left by its early inhabitants to study what they ate. The earliest material at the bottom of the garbage heaps was about 1,200 years old, although this earliest date is still being debated. That is about when the first Polynesians colonized the island, and that is when the pollen data show the forest decline beginning. The earliest garbage consisted in large part of bones from dolphins (porpoises), sea turtles, seals, shellfish, and fish.

The Polynesian settlers also brought rats with them to Easter Island. Rat bones were found throughout the garbage mounds. These rats were probably a food source for the colonizers, and they probably caused significant ecological harm to the island’s birds and trees by eating seeds and bird eggs.

Aside from shellfish, seafood can be acquired only with the use of boats. Yet scientists found fewer and fewer remains of seafood as time went on. The tops of the garbage mounds had no seafood whatsoever.

In some cases, scientists found cracked human bones in the garbage mounds, but only in the most recent parts of the piles. This evidence indicates that cannibalism began around 1600 on the island. Scientists hypothesize that when the forests were gone, the islanders could no longer build boats to fish. Famine, population collapse, and cannibalism followed.

How Is a Hypothesis Different from a Theory?

As the story of Easter Island started to unfold, scientists concluded that its inhabitants destroyed their forests, perhaps in large part to move statues. The statues are thought to have been a display of political power. It is thought that powerful chiefs competed to build the biggest and the most statues, at the expense of the well-

A scientific hypothesis is a specific testable idea. Theories are constructed from many hypotheses that are all tested and supported by the available evidence. Successful theories hold up as new evidence becomes available through time. Any theory can fail if new data contradict it. When this happens, either the theory must be adjusted or it must be thrown out altogether.

Some theories are called unifying theories because they explain a wide range of seemingly unrelated phenomena. The theory of plate tectonics (see Chapter 11), for example, is a unifying theory that explains a wide range of physical phenomena, such as volcanoes, earthquakes, and mountain building.

In some cases, theories are so strong that no one reasonably thinks that new facts will ever refute them. In such a case, the theory is elevated to a scientific law. The law of gravity is an example. If apples or anything else were ever to fall upward, the law of gravity would have to be modified, or even abandoned.