10.5 Bundling

When to Use It Bundling

A firm has market power and can prevent resale.

A firm sells a second product and consumers’ demand for that product is negatively correlated with their demand for the first product.

bundling

A pricing strategy in which the firm sells two or more products together at a single price.

Another indirect price-

When you subscribe to cable or satellite television, for example, you are buying a bundled good. You pay a single monthly fee for service, and the cable or satellite company delivers a number of networks together. You don’t pick and choose every channel individually. For your $45 per month, you get, say, 90 channels rather than paying $6 per month for ESPN, $4 a month for MTV, and so on.

Sometimes, things can be bundled just because people prefer buying things together. Think about a pair of basketball shoes. Although shoemakers could sell shoes individually, there really isn’t much demand for single shoes or for mixing a Nike basketball shoe for the left foot with an Under Armour shoe for the right. People want to buy both shoes together. This sort of bundling, which occurs because the goods are strong complements to each other (i.e., one good raises the marginal utility of the other), is not a price-

In this chapter, we’re interested in ways that companies can use bundling as a way to price-

Take a cable company providing TV channels to your home. To make it easy, let’s say there are only two cable networks: the sports network ESPN and History, a channel that specializes in programming on historical topics (ESPN is among the most watched cable networks, and History is not). Why would the cable company force you to buy both as a bundle for some price rather than just sell them separately?

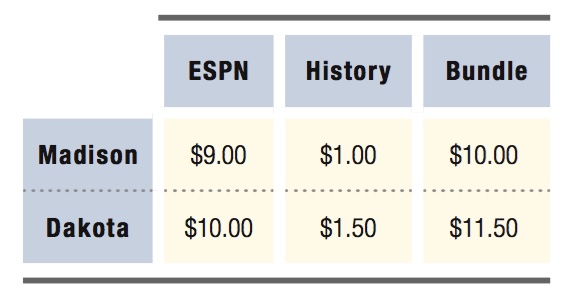

At first glance, people tend to think it’s a way for the cable company to leverage market power/high demand for ESPN to force people to pay more for the lesser product (History). But this “forcing it down their throat” argument usually does not make sense. To see why, suppose there are two customers (Madison and Dakota) in the market. Both like ESPN a lot and History less, as reflected in Table 10.2. Madison values ESPN at $9 per month and Dakota values it at $10 per month. Madison values History at $1 per month, while Dakota values it at $1.50. For simplicity, let’s assume the marginal cost of supplying the networks is zero.

Does the cable company raise its producer surplus by bundling the prized ESPN with History? If it sells the channels separately, it would have to price each channel at the lower of the two customers’ valuations for each channel ($9.00 for ESPN and $1.00 for History). Otherwise, the company would sell to only one of the customers and would lose the revenue from the other.7 Thus, it sells ESPN for $9 per month and History for $1 per month, earning a total surplus of $20 per month (2 × $9) + (2 × $1) from selling the channels separately.

405

Now suppose the cable company sells the channels as a bundle. The combined value the customers put on the bundle ($10.00 per month for Madison and $11.50 for Dakota) means the company will again set the price at the lower valuation so it won’t lose half of the market. It therefore prices the bundle at $10 and sells it to both customers. This yields a surplus of (2 × $10), or $20 per month, the same amount it earned selling the networks separately. Bundling has not raised the firm’s surplus.

Furthermore, if the company combines ESPN with something customers don’t actually want at all (say, e.g., that the valuation on History was zero or even negative), then the amount that customers would be willing to pay for that network plus ESPN would be that much lower. As a general matter, then, a company can’t make extra money by attaching a highly desired product to an undesired one.

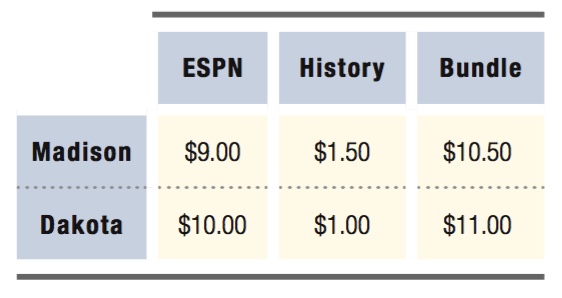

How should a firm bundle products to make more producer surplus? Suppose that, instead of the valuations being what they are in Table 10.2, the two valuations for History are switched. Both customers value ESPN far more, but now Madison has a higher valuation for History ($1.50 per month) than does Dakota ($1.00). The key condition that has changed, as will become clear in a minute, is that the willingness to pay for the two goods is now negatively correlated across the consumers. This means that one of the customers has a higher willingness to pay for one channel than the other customer, but a lower willingness to pay for the other channel. In our example, Madison has lower willingness to pay for ESPN than Dakota but greater demand for History, as shown in Table 10.3.

With this change, the firm receives more producer surplus using the bundling strategy. If the cable company sells the channels separately, the calculation is the same as before: ESPN for $9 per month, History for $1, and earns a total of $20 of surplus per month. If the firm bundles the channels, however, it can sell the package to both customers for $10.50 per month. This earns the company (2 × $10.50) or $21 of producer surplus per month, more than the $20 per month from selling the channels separately.

The reason why bundling works in the second scenario is the negative correlation between the two customers’ willingness to pay, which occurs because Dakota values one part of the bundle (ESPN) more than Madison, while Madison values History more than Dakota. If the cable company wants to sell to the entire market, it can only set a price equal to the smaller of the two customers’ willingness to pay, whether pricing separately or as a bundle. In the first example with positively correlated demand (when Dakota had a higher willingness to pay for both channels), the lower of the customers’ valuations for the bundle ($10 per subscriber for Madison) is smaller by $1.50 than the larger valuation ($11.50 per month for Dakota) because it reflects Madison’s lower valuations for both channels. Therefore, if the cable company wants to sell the channels as a bundle, it must offer Dakota a discount that embodies the fact that Madison has a lower willingness to pay for both channels. As a result, the cable company does no better than having sold the channels separately.

406

With a negative correlation of demands across customers, there is less variation (only $0.50) in each customer’s willingness to pay for the bundle: $10.50 per month for Madison and $11.00 per month for Dakota. This reduced variation means the cable company doesn’t need to give as large a discount to Dakota to sell to both customers. Bundling has reduced the difference in total willingness to pay across the customers. What’s important is that the smaller of the two combined valuations is larger when the channel demands are negatively correlated. Madison will pay $10.50 instead of only $10, which allows the company to raise its price. In this way, bundling allows sellers to “smooth out” variations in customers’ demands, raises the prices sellers can charge for their bundled products, and increases the amount of surplus they can extract.

Mixed Bundling

mixed bundling

A type of bundling in which the firm simultaneously offers consumers the choice of buying two or more products separately or as a bundle.

The previous example shows why a firm might choose to sell two products as a bundle instead of separately. Sometimes, however, firms simultaneously offer the products separately and as a bundle and then let the consumer choose which to buy. This indirect pricing strategy is called mixed bundling. An Extra Value Meal at McDonald’s includes a sandwich, fries, and a drink for one price. McDonald’s also offers these three menu items individually. This is where mixed bundling acts as a form of indirect price discrimination because the firm offers different choices and lets customers sort themselves in ways that increase producer surplus.

pure bundling

A type of bundling in which the firm offers the products only as a bundle.

Mixed bundling is a lot like the bundling strategy we’ve just discussed (offering only the bundle is often called pure bundling). It is useful in the same type of situations, but is better than pure bundling when the marginal cost of producing some of the components is high enough that it makes sense to let some customers opt out of buying the entire bundle.

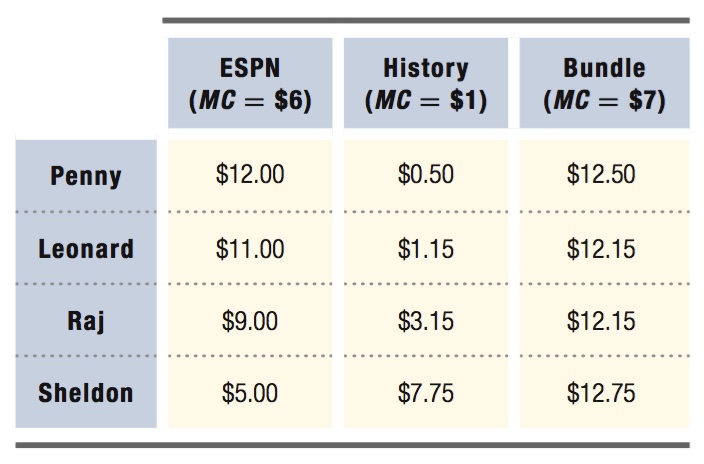

Returning to our cable network example, let’s suppose there are four customers and that they value the networks according to Table 10.4. The willingness to pay is negatively correlated across the networks, so we know bundling can work as a pricing strategy.

Now suppose instead of marginal costs being zero, the marginal cost of supplying ESPN is $6.00 per month and History is $1.00 per month. Therefore, the marginal cost of producing the bundled package is $7.00. If the cable company sells the bundle for $12.15 (the minimum valuation of the bundle across the customers), it will sell the bundle to all four customers. Subtracting costs, this will net a per-

But look more closely at Penny and Sheldon. Their relative values for the two channels are extreme. Penny really values ESPN and barely values History, while the opposite is true for Sheldon. And crucially, the value they put on one of these channels is below the marginal cost of supplying it: History for Penny and ESPN for Sheldon. As we will see, in these cases it makes sense for the cable company to try to split these customers off from the bundle, because it does not want to supply channels to customers who value them at less than the cost of providing them.

407

Figuring out the right mixed bundling strategy is slightly complicated because of incentive compatibility, so we’ll take it one step at a time. Given the issues we just discussed, the cable company would like to end up selling the bundle to Leonard and Raj, only ESPN to Penny, and only History to Sheldon. Because both Leonard and Raj value the bundle at $12.15 per month, that’s a reasonable starting point for thinking about the price of the bundle. If this is the price of the bundle, however, the company can’t charge Sheldon his full $7.75 valuation for History. If it tried to, Sheldon would choose the bundle instead because it would give him 60 cents more consumer surplus ($12.75 – $12.15) than if he bought only History (consumer surplus of zero if priced at $7.75). A price of $7.75 for History is therefore not incentive-

We can do the same type of calculations with ESPN and Penny. The cable company can’t charge $12.00 for ESPN alone, because Penny would opt for the bundle to get 35 cents ($12.50 – $12.15) of consumer surplus rather than zero from buying ESPN at $12.00. So, the company has to leave Penny with at least 35 cents of surplus from buying just ESPN. The highest price that will achieve this is $12.00 – $0.35, or $11.65. Again, offering this option won’t move Leonard and Raj away from the bundle, because both value ESPN at less than $11.65.

So with those three prices—

Producer surplus has increased because the cable company has saved itself the trouble of delivering a product to a customer who values it at less than it costs to produce.

figure it out 10.4

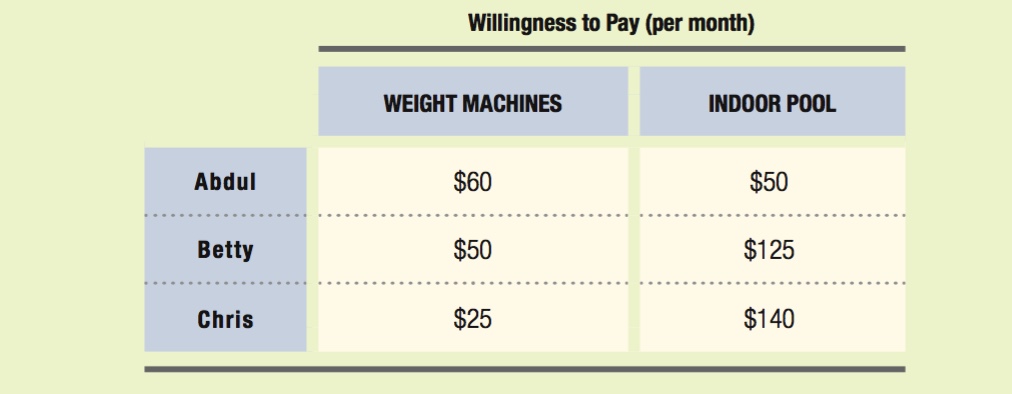

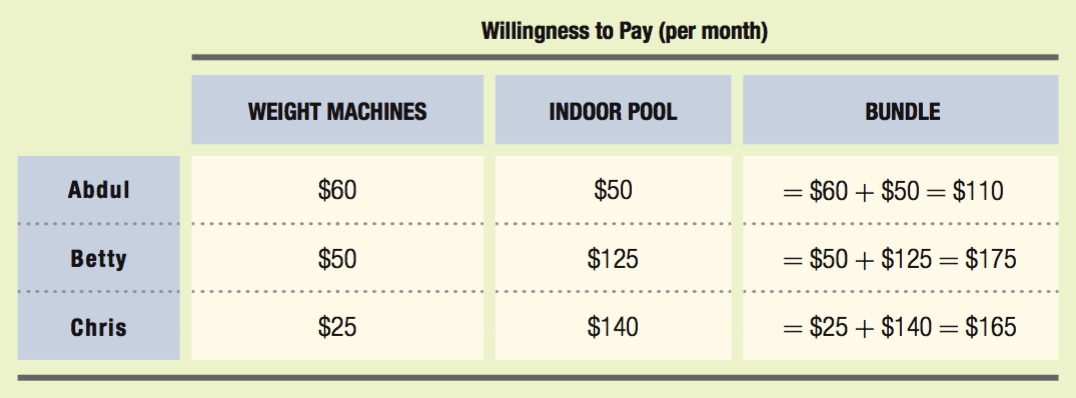

Fit Club, Inc. is a health club that offers two types of equipment: weight machines and a swimming pool. There are currently three customers (Abdul, Betty, and Chris), whose willingness to pay for using each type of equipment per month is listed in the table below:

The weight room and the swimming pool each have a constant marginal cost of $20 per month. In the case of the pool, the marginal cost is the price of the water and chemicals used, while the marginal cost of the weight machines is the cost of cleaning and maintaining them. Each customer is considering monthly access to each type of equipment, and the firm has to decide what type of membership package to offer the customers.

408

What price will the firm charge for each product if it wishes to sell a health club membership to all three customers? What is the firm’s producer surplus if it sells separate access to the weight room and the pool room at these prices?

What price will the firm charge for a bundle of access to both the weight room and the swimming pool if it wishes to sell the bundle to all three customers? How much producer surplus will Fit Club, Inc. earn in this case?

Suppose the firm is considering offering its customers a choice to either purchase access to the weight room and the swimming pool separately at a price of $60 for the weight machine and $140 for the pool, or to purchase a bundle at a price of $175. Which option will each customer choose? How much producer surplus will Fit Club, Inc. earn in this situation?

Solution:

To sell access to the weight machines to all three customers, the health club must charge a price no greater than $25, the lowest willingness to pay of the customers (Chris). For the same reason, the price for the pool will be $50.

At these prices, the firm’s producer surplus for its sales of access to the weight machines will be

Producer surplus for weight machine = (price – marginal cost) × quantity

= ($25 – $20) × 3

= ($5)(3) = $15

For access to the pool, producer surplus will be

Producer surplus for the pool = ($50 – $20) × 3

= ($30)(3) = $90

Total producer surplus will be $15 + $90 = $105.

To determine the price of the bundle, we need to calculate each buyer’s willingness to pay for the bundle. This is done simply by summing the customers’ willingness to pay for each product as shown in the table below:

So, the maximum price the health club can charge for its bundle (and still sell to all three buyers) is $110. It will sell three bundles at this price. Therefore, its producer surplus will be

Producer surplus for bundle = (price – marginal cost) × quantity

= ($110 – $40) × 3

= ($70)(3) = $210

409

We need to compare each buyer’s willingness to pay to the prices set for purchasing access to each room separately and the price of the bundle.

Abdul will only purchase a weight machine membership. His willingness to pay for the pool is below the price of $140. The same is true for the bundle, which he values only at $110. Therefore, the health club will only sell Abdul access to the weight machines.

Betty will not be willing to buy either membership separately, because her willingness to pay for each is below the set price. However, Betty’s willingness to pay for the bundle ($175) is exactly equal to the price, so she will purchase the bundle.

Chris will only purchase access to the indoor pool. His willingness to pay for weight machines is only $25, far below the price of $60. Likewise, Chris is willing to pay at most $165 for the bundle. Thus, the health club will only be able to sell pool access to Chris.

Total producer surplus will therefore be

Producer surplus for weight machines = (price – marginal cost) × quantity

= ($60 – $20) × 1

= $40

Producer surplus for the pool = ($140 – $20) × 1

= $120

Producer surplus for bundle = ($175 – $40) × 1

= $135

Total producer surplus when the health club offers customers a choice of bundling or separate prices is $40 + $120 + $135 = $295.