11.7 Monopolistic Competition

Model Assumptions Monopolistic Competition

Industry firms sell differentiated products that consumers do not view as perfect substitutes.

Other firms’ choices affect a firm’s residual demand curve, but the firm ignores any strategic interactions between its own quantity or price choice and its competitors’.

There is free entry into the market.

monopolistic competition

A market structure characterized by many firms selling a differentiated product with no barriers to entry.

In the models we’ve studied so far, we haven’t considered the possibility that other firms might want to enter markets in which firms are earning positive economic profits. Presumably, other firms exist that would like a piece of that action. If there are no barriers to entering a market such as the snowboard market, an additional firm will cause Burton and K2’s profits to decline. We saw in the Cournot model that adding more firms to the industry drove the equilibrium closer to perfect competition. In this section, we look at our last model of imperfect competition, and see what happens when there is entry into a market with differentiated products. Monopolistic competition is a market structure characterized by many firms selling a differentiated product with no barriers to entry. This term might sound like an oxymoron—

454

Every firm in a monopolistically competitive industry faces a downward-

Many markets are monopolistically competitive. For example, there are hundreds of fast-

Keep in mind that, while monopolistic competition is categorized as “imperfect competition” along with oligopoly, there are differences between these two market structures. One is that oligopoly markets have barriers to entry, while monopolistically competitive markets do not. However, the key distinction between oligopoly and monopolistic competition is the assumption about strategic interaction. In an oligopoly, firms know that their production decisions affect their competitors’ optimal choices, and all oligopolistic firms take this feedback effect into account when making their decisions. On the other hand, in monopolistic competition, firms do not worry about the production decisions of their competitors because the impact of any competitor on another is assumed to be too small for these firms to be concerned about.

Equilibrium in Monopolistically Competitive Markets

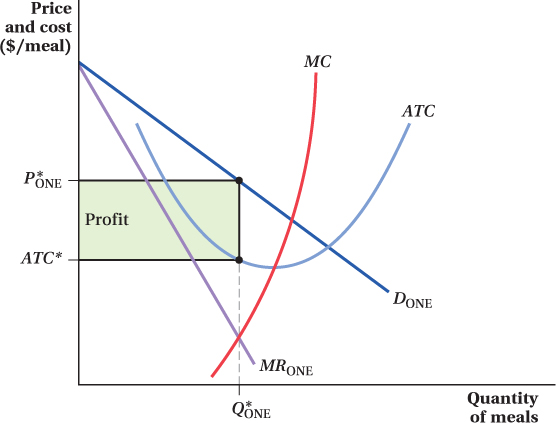

To analyze monopolistically competitive markets, let’s look at a single company with market power—

Because the restaurant in Figure 11.6 is a monopolist, it produces where its marginal revenue equals marginal cost, Q*ONE. The price it charges is P*ONE In addition to the marginal cost of production, however, the restaurant has to pay fixed cost equal to F (this fixed cost is the reason why the firm’s average total cost curve is U-

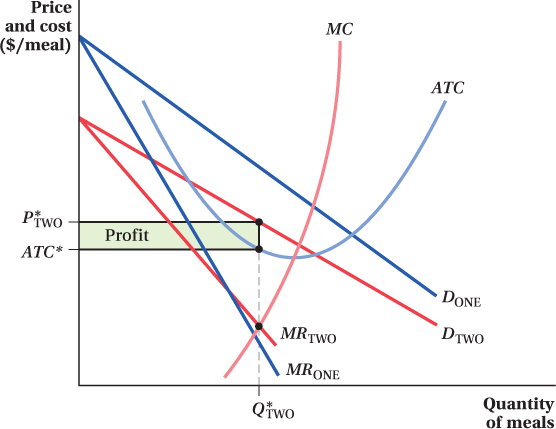

So far, this market is just a regular monopoly. But now suppose another restaurateur notices that this firm makes economic profit and decides to open a second, slightly different fast-

The key to understanding what happens in monopolistically competitive markets is to recognize what happens to the demand curve(s) of the market’s existing firm(s) when another firm enters. We know that when there are more substitutes for a good available, the demand curve for the initial good becomes more elastic (less steep). Having another restaurant open up means that more substitution possibilities now exist for consumers. Instead of there being one firm with a demand curve, as in Figure 11.6, the entry of a second firm means each restaurant now has a demand curve that is a bit flatter than the monopolist firm’s demand curve. And, because the demand is being split across two firms, not only is the monopolist firm’s demand curve flatter, but it has shifted in as well. Figure 11.7 shows this change from one to two firms, as the initial (monopolist) firm’s demand curve (now it is a residual demand curve) shifts from DONE to DTWO . Notice how DTWO is both flatter than DONE and to the left of it. The marginal revenue curves also shift accordingly. (The figure illustrates only what’s going on for one of the two firms in the market; the picture is exactly the same for the other firm.)

455

456

Even after entry, however, both firms are essentially monopolists over their own residual demand curves. Each individual firm’s demand curve reflects the fact that (1) it is splitting the market with another firm and (2) the presence of a substitute product makes the firm’s demand more elastic. The competitor’s presence is accounted for, but it is incorporated in the firm’s residual demand curve. In monopolistic competition, the firm takes this residual demand as given. This is different from the oligopoly models we covered, in which firms realize that their actions affect the desired actions of their competitors, which in turn affect their own optimal action, and so on. This strategic interaction is captured in firms’ reaction curves. A monopolistically competitive firm, on the other hand, acts like it is in its own little monopoly world, even though its competitors’ actions affect the residual demand it faces. This assumption about monopolistically competitive firms’ ignorance of strategic interactions is more likely to hold in industries where there are a large number of firms selling related but differentiated products such as car washes, self-

Assuming the two firms have identical residual demand curves, both produce the quantity Q*TWO at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost and charge the profit-

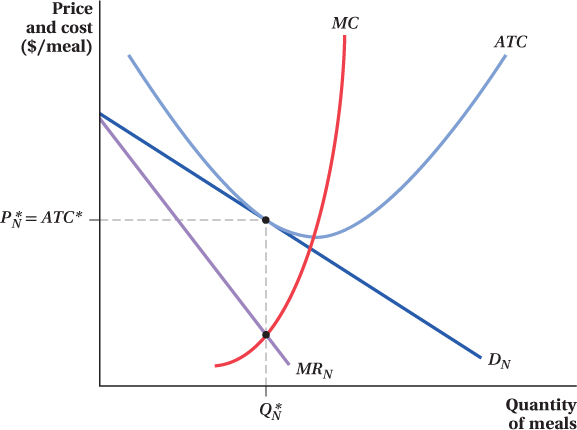

Because two firms in the market make positive economic profit, still more firms will want to enter. Each new firm that enters will further shift the other individual companies’ demand curves to the left and make them more elastic (flatter).

Entry will cease only when industry firms are no longer making economic profit. At that point, the market will look like Figure 11.8. When there are N firms in the market, each firm’s residual demand curve eventually shifts back to DN . Faced with this demand curve, the firm produces the quantity Q*N at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost, charges a price of P*N , and earns zero economic profit.

457

Why does economic profit equal zero at this point? Look at where the firm’s average total cost curve is relative to its demand curve. The two curves are tangent at Q*N and P*N. If price equals average total cost, profit is zero. The firm is just covering its costs of operation (variable and fixed) at this point.

Here’s an important point about monopolistically competitive markets: Even though entry occurs until profits are zero, the entry process does not ultimately lead to a perfectly competitive outcome in which price equals marginal cost. Firms in a monopolistically competitive market face a downward-

figure it out 11.5

Sticky Stuff produces cases of taffy in a monopolistically competitive market. The inverse demand curve for its product is P = 50 – Q, where Q is in thousands of cases per year and P is dollars per case.

Sticky Stuff can produce each case of taffy at a constant marginal cost of $10 per case and has no fixed cost. Its total cost curve is therefore TC = 10Q.

To maximize profit, how many cases of taffy should Sticky Stuff produce each month?

What price will Sticky Stuff charge for a case of taffy?

How much profit will Sticky Stuff earn each year?

In reality, firms in monopolistic competition generally face fixed costs in the short run. Given the information above, what would Sticky Stuff’s fixed costs have to be in order for this industry to be in long-

run equilibrium? Explain.

Solution:

Sticky Stuff maximizes its profit by producing where MR = MC. Since the demand curve is linear, we know from Chapter 9 that the MR curve will be linear with twice the slope. Therefore, MR = 50 – 2Q. Setting MR = MC, we get

50 – 2Q = 10

Q = 20

Sticky Stuff should produce 20,000 cases of taffy each year.

We can find the price Sticky Stuff will charge by substituting the quantity into the demand curve:

P = 50 – Q = 50 – 20 = $30 per case

Total revenue for Sticky Stuff will be TR = P × Q = $30 × 20,000 = $600,000. Total cost will be TC = 10Q = (10 × 20,000) = $200,000. Therefore, Sticky Stuff will earn an annual profit of π = TR – TC = $600,000 – $200,000 = $400,000.

Long-

run equilibrium occurs when firms have no incentive to enter or exit. Therefore, firms must be earning zero economic profit. From (c), we know that Sticky Stuff is earning a profit of $400,000. In order for its profit to be zero, Sticky Stuff must face annual fixed costs equal to $400,000.

See the problem worked out using calculus

See the problem worked out using calculus