13.4 The Labor Market in the Long Run

Our labor market analysis up to this point has been for the short run when the firm’s level of capital is fixed. Now we look at what happens when the firm can change its capital level.

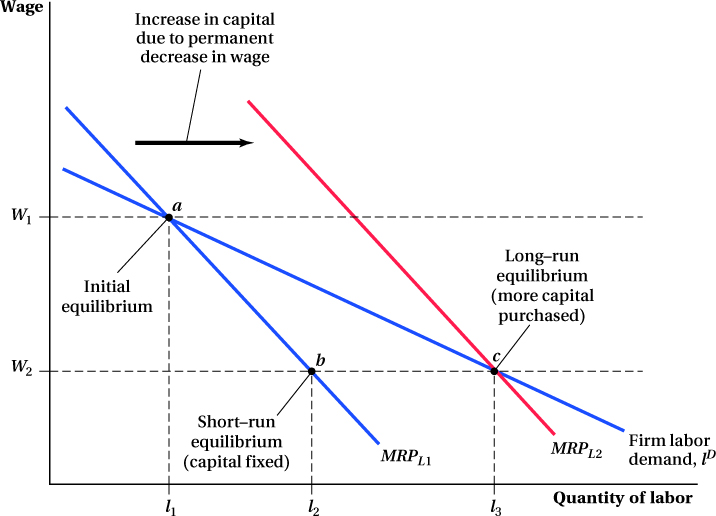

Earlier we learned that changes in the amount of capital a firm has alter the marginal product of labor MPL and thus shift the short-

Suppose that there is a permanent drop in the market equilibrium wage, as shown in Figure 13.8. The firm initially has a short-

524

FREAKONOMICS

Competition in the Market for Economists

Fifteen years ago, the average salary for academic economists was $58,730. The comparable number for historians was only a little bit lower—

What explains the divergence in wages between academic economists and historians? Ironically, it likely has little or nothing to do with academics. Rather, the reasons for economists’ rising salaries are two changes that took place on Wall Street. The first change is that Wall Street salaries, which were already high, have skyrocketed over the last fifteen years. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, employees in “Securities, Commodity Contracts, and Other Financial Investments and Related Activities” working in New York City earned an average pay of $384,344 in 2014.C The second change is that, over time, the set of skills that one learns when getting an economics degree have become more and more highly prized. Quantitative models, economic analysis, and the study of behavioral anomalies have become the norm in the finance industry. Sadly for historians, Wall Street has not (yet) come to appreciate the value of a good historical narrative.

So even though the day-

Just because universities compete with Wall Street for economists doesn’t mean, however, that they need to match Wall Street salaries dollar for dollar. For many people, being a professor is a much more attractive job (fewer hours, more freedom, less stress, the joy of interacting with students, among other perks). Thus, all else equal, most economics PhDs are willing to take a large (but not infinitely large) salary hit to go into academics.

The good news for you—

And if you need any additional evidence of the power of economics, you need look no further than the trends in college major choices. At the University of Wisconsin-

525

In the long run, however, this is not the total effect of the lower wage. The increase in labor hired to l2 also raises the firm’s marginal product of capital because, as we saw in Chapter 6, for most production functions, having more of one input raises the marginal product of the other. The increase in the marginal product of capital gives the firm an incentive to purchase more capital. When it does, the additional capital, in turn, raises the firm’s marginal product of labor, and thus its marginal revenue product of labor. The increased MRPL increases the amount of labor the firm demands at each wage and shifts out the firm’s short-

Step back for a second and think about the total effect of the decreased wage on the firm’s quantity of labor demanded. At wage W1, the firm demanded the quantity of labor l1. When the wage fell to W2, once it had enough time to adjust its amount of capital, the firm ended up demanding quantity l3. Therefore, the curve running through points a and c in Figure 13.8, lD, is the firm’s long-

The long-