Problems

(Solutions to problems marked * appear at the back of this book. Problems adapted to use calculus are available online at www.macmillanhighered.com/

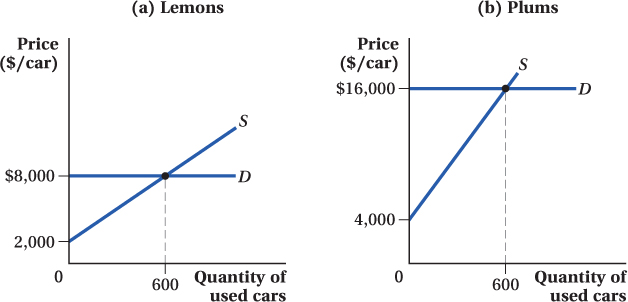

Consider the market for used cars shown in the figure below. The top panel (a) shows the market for low-

quality cars (lemons); the bottom panel (b) shows the market for high- quality cars (plums). If all buyers and sellers had full information about the quality of automobiles being offered for sale, lemons would sell for $8,000 and plums would sell for $16,000.

Suppose that buyers recognize that the chance of getting a lemon is 50%, but they are unable to tell whether a car is a lemon or a plum. What is the expected value of a used car to a buyer?

If the market works to the extent that prices reflect the expected value of a used car, how many high-

quality automobiles will be offered for sale at the price determined in (a)? How many low- quality automobiles will be offered for sale? Of the automobiles offered for sale, what is the proportion of low- quality automobiles? Compared to a market with perfect information, what kind of deadweight loss does the information loss generate in the market for high-

quality used cars? Is there a deadweight loss in the market for low- quality cars, too?

In Problem 1, we discovered that imperfect information about the quality of used cars caused fewer plums and more lemons to be offered for sale. Thinking in discrete steps,

How does this revision of the expected value affect the proportion of lemons to the total number of cars offered for sale by sellers?

How does the change in the proportion of lemons to the total number of cars offered for sale affect buyers’ willingness to pay for a used car?

How does the change in market price (buyers’ willingness to pay) affect the quantity of plums and the quantity of lemons offered for sale?

Briefly describe the logical conclusion of this feedback process.

In an isolated town, there are two distinct markets for cars. Buyers will pay up to $12,000 for a high-

quality car or $8,000 for a low- quality car. There are 100 high- quality cars for sale, and the sellers have a minimum acceptable price of $11,000. There are also 100 low- quality cars for sale at a minimum acceptable price of $5,000. The supply of automobiles is perfectly inelastic above the reservation price. 647

If there is perfect information, how many high-

quality and how many low- quality cars will be sold? If there is perfect information, 100 high-

quality cars and 100 low- quality cars will be sold. Suppose that the quality of a car is known to the seller, but not to the buyer. What price will prevail in the marketplace if buyers correctly estimate the chance of acquiring a low-

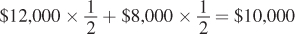

quality car at 50%? What happens to the number of high- quality cars for sale at that price? If the quality of the car is not known to the buyer, the expected value of a used car to a buyer is

No high-

quality cars will be offered for sale at that price as it is below the minimum acceptable price of $11,000. After sellers make all adjustments, what will the equilibrium price of cars be? What proportion of those cars will be high-

quality cars? No high-

quality cars will be offered for sale and the equilibrium price will range between $5,000 and $8,000 depending on the negotiation skills of buyers and sellers of low- quality cars. What happens to your answers to (a), (b), and (c) if sellers of high-

quality cars have a reservation price of $9,500 instead of $11,000? If there is perfect information, the answer to part (a) does not change. Similarly, the market price for a used car will remain the same, $10,000, as buyers’ valuation has not changed. Given the reservation price of $9,500 of the high-

quality sellers, 100 high- quality cars will be offered for sale as the price for a car exceeds the reservation price of high- quality car sellers. Moreover, 100 low- quality cars are also offered for sale at $10,000. All in all, the equilibrium price will be $10,000 and the proportion of high- quality cars to all cars will be  .

.

In the 1960s Yale University began offering students an alternative to taking out student loans. Instead, students could attend Yale in exchange for a specified percentage of their earnings over a significant length of time. Yale used historical data to determine the percentage so that the program would pay for itself—

large payments from high earners would offset the smaller payments from low earners. If you were planning on becoming a Wall Street financier, would you be more likely to take out loans or enroll in the Yale program? Why?

If you were planning on becoming a missionary, would you be more likely to take out loans or enroll in the Yale program? Why?

The tuition program turned out to be a financial disaster for Yale. Do your answers to (a) and (b) shed light on why? Explain.

What kind of information problem did the Yale program suffer from?

Toyota regularly takes its own cars in trade for new models. It then subjects them to a rigorous inspection process, fixing defects as it goes, and offers them for sale with an extended warranty. Explain how these procedures help Toyota deal with the adverse selection problem.

A few years ago, a new online insurer appeared. Found at www.ticketfree.org, the insurer offered, for a price, up to $500 of coverage against speeding tickets.

Who has more valuable information in this potential transaction, the buyer of speeding ticket insurance or the seller?

The buyer has more valuable information as he knows his driving type.

Explain why the existence of information asymmetries creates an adverse selection problem in the market for speeding ticket insurance.

Buyers are aware if they are likely to be caught for speeding. Thus, those choosing to enroll in the coverage are the speedy drivers. Those who do not exceed the speed limit will not buy the coverage. Hence, this asymmetric information creates an adverse selection problem in the market.

What is likely to happen to the behavior of both faster and slower drivers once they have purchased speeding ticket insurance? What is this kind of problem called?

Both types will be less careful and drive faster once they buy coverage. This kind of behavioral response is called moral hazard.

Ticketfree.org is no longer in operation. Use your answers to (b) and (c) to explain why.

The insurance was most likely overwhelmingly purchased by those drivers who were inclined to speed. Moreover, drivers are likely to be less careful once they have purchased coverage. Thus, revenues earned from insurance premiums were likely insufficient to offset the costs of paying out claims.

To assist in ensuring adequate and affordable health care for all, the federal government has mandated that health insurers provide health insurance to all, regardless of their physical condition. Insurers may not reject coverage for preexisting health problems.

Explain why this mandate, standing alone, creates tremendous potential for adverse selection problems.

A second part of recent health-

care reforms is a mandate that every person must either obtain insurance through his employer or through the private market. Explain how this mandate reduces (i) adverse selection problems in general and (ii) the adverse selection problems discussed in part (a) in particular.

Many health and casualty insurance policies require policyholders to pay a certain amount (called a deductible) for claims before the insurer itself will begin to pay.

Explain how the existence of a deductible reduces the problems of moral hazard.

Often, insurers will let policyholders choose a low deductible, or will offer them a larger deductible in exchange for a substantial reduction in the premium. Explain how this two-

tiered system helps insurers deal with the problem of adverse selection.

After a probationary period of six years, during which they teach, research, and serve on committees, university professors who meet acceptable standards are given tenure. Tenure offers these professors tremendous job security.

Explain why a tenure system makes universities susceptible to a moral hazard problem.

Explain why the problems of moral hazard caused by tenure are likely to be greater than the problems of adverse selection.

Suppose that, to deal with adverse selection problems, a new federal lemons law requires all used car dealerships to provide a one-

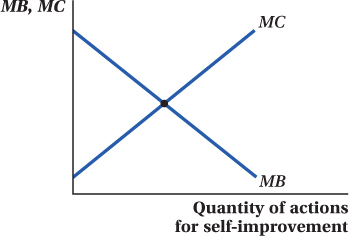

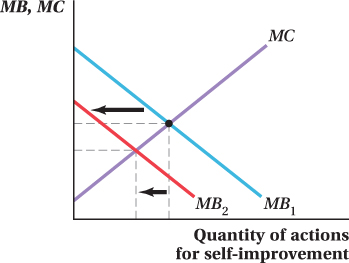

year warranty for each car they sell. Explain how this new law, designed to reduce adverse selection, might increase the problem of moral hazard. Harry is dating Sally. Because he is devastated at the thought of being dumped, he spends considerable resources making himself attractive to her: expensive haircuts, ballroom dancing classes, a gym membership, and so on. Harry’s marginal cost of making himself attractive to Sally is given by MC in the graph below. Sally, of course, appreciates his efforts: The marginal benefit Harry receives from his efforts (which account for the probability of being dumped) is shown as MB.

648

On the graph, determine the optimal amount of resources Harry should expend making himself more attractive to Sally.

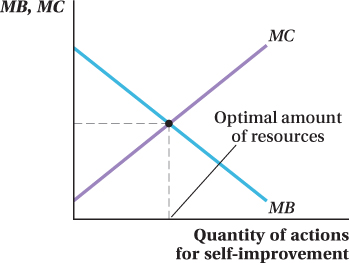

Harry marries Sally. The marriage contract raises the cost of exiting a relationship, and thus, for any given level of Harry’s expenditure, Sally is less likely to dump Harry. Illustrate the effects of the marriage contract in the accompanying graph by shifting the appropriate curve in the appropriate direction.

There is a shift-

in of the marginal benefit curve (to the left), which leads to a smaller optimal quantity of actions for self- improvement.

“Harry has really let himself go since we got married. He burps too much, seldom shaves, and never takes out the trash.” Is this commonly heard statement consistent with the illustration you have drawn?

Yes, it is consistent with the illustration. The quantity of actions for self-

improvement decreased. What kind of problem does this illustrate: adverse selection or moral hazard?

It is a moral hazard problem, as Harry’s behavior is likely to change with the change in incentives.

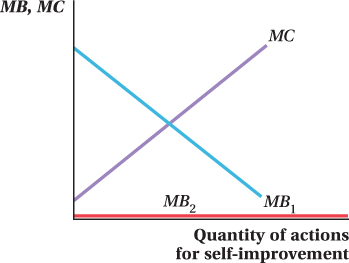

A “covenant marriage” is one that is virtually impossible to exit for a given period of time. Illustrate the effects of a covenant marriage on your graph, and comment on the predictions your graph holds for the quality of relationships fostered by covenant marriages.

The marginal benefit curve is a horizontal line with an optimal amount of actions for self-

improvement at 0. SB-

28

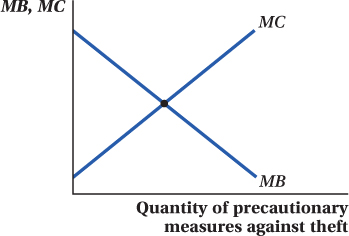

Consider the graph, which demonstrates the costs and benefits of theft-

proofing one’s home. The marginal costs increase as more precaution is taken: It’s cheap to install good locks, but more difficult to install invisible laser intruder- detection systems. The marginal benefit declines as more precaution is taken: If I am a burglar, adding a guard dog isn’t going to provide much deterrence if you already have an electric fence and 30 locks on each door and window.

Determine the optimal amount of precaution the homeowner would take if theft insurance were unavailable.

Suppose that the homeowner can obtain an insurance policy that covers half of any losses he might suffer. Assuming that the marginal benefit curve represents dollar losses to the homeowner, shift the marginal benefit curve by an appropriate distance and determine what happens to the homeowner’s optimal amount of care.

Suppose that the insurance company decides to institute a deductible: The homeowner pays the first $1,000 of losses, and after that the insurance company splits the losses with the homeowner 50-

50. Shift the marginal benefit curve by an appropriate amount (be sure to indicate the magnitude of the shift in an appropriate fashion). What effect does the deductible have on the precautions taken by the homeowner?

After years of training, Sara has landed a contract playing professional lacrosse. Eager to leverage her pro status by bringing in endorsements, she asks Jenny MacGuire to be her personal manager. Jenny has offered Sara a choice of two payment plans. Sara can engage Jenny’s services for a flat fee of $100,000. Alternatively, Sara can pay Jenny 15% of all endorsement revenue.

Sara estimates that if Jenny expends modest effort ($20,000 worth) in her job, she will generate $600,000 in endorsement revenue for Sara. But if Jenny expends high effort ($50,000 worth), she will bring in $1 million in endorsements.

Suppose Sara agrees to the flat-

rate plan. What can Sara expect to receive if Jenny expends modest effort? If Jenny expends high effort? What can Jenny expect to receive in either case? Explain the associated principal– agent problem. Who is the principal? Who is the agent? If Jenny expends modest effort, Sara can expect to receive $600,000 in revenue, but will spend $100,000 on Jenny’s services, for a net of $500,000. If Jenny expends high effort, Sara can expect to receive $1 million in revenue, but will spend $100,000 on Jenny’s services, for a net of $900,000.

If Jenny expends modest effort, she will be paid $100,000 while expending $20,000 of effort, for a net of $80,000. If Jenny expends high effort, she will be paid $100,000 while expending $50,000 of effort, for a net of $50,000.

Here, Sara is the principal and Jenny is her agent. The problem is that Jenny expending high effort is in Sara’s best interest, but Jenny expending modest effort is in Jenny’s best interest.

For both possible effort levels, determine the rewards to Jenny and Sara if Sara chooses the 15% plan. What happens to the principal–

agent problem if Sara chooses this plan? Under the 15% plan, if Jenny expends modest effort, Sara can expect to receive $600,000 in revenue, but will spend $90,000 on Jenny’s services, for a net of $510,000. If Jenny expends high effort, Sara can expect to receive $1 million in revenue, but will spend $150,000 on Jenny’s services, for a net of $850,000.

If Jenny expends modest effort, she will be paid $90,000 while expending $20,000 of effort, for a net of $70,000. If Jenny expends high effort, she will be paid $150,000 while expending $50,000 of effort, for a net of $100,000.

The 15% payment scheme makes the principal agent problem disappear: Expending high effort is not only in Sara’s best interest, but it is also in Jenny’s.

649

The board of directors of a major corporation is trying to determine how to structure the salary of the new CEO. One option is for the board to offer the new CEO a flat salary of $1 million per year. A second option is to offer a profit-

sharing plan with a base salary of $200,000 plus 10% of the firm’s profit. If the CEO puts a lot of effort into the job, she will generate a $10 million profit for the firm. If the CEO exerts modest effort, the corporation will earn $7 million in profit. Expending a lot of effort costs the CEO $500,000; expending modest effort costs her $300,000. Draw the extensive-

form game tree for the game played between the board and the CEO. Assume that the board moves first, choosing the type of salary offer. Assume that the CEO moves second, choosing her effort level. Be sure to enumerate payoffs to the board (and the shareholders they represent) and the CEO. What is the equilibrium outcome for this game? What kind of contract should the board offer? What level of effort should the CEO choose?

Consider the questions faced by the board and the CEO in Problem 14. Assume that, as before, expending modest effort costs the CEO $300,000. But, assume now that expending high effort costs the CEO $750,000.

Draw the extensive form for this game and find the equilibrium. Does the change in the cost of high effort alter the outcome? Explain.

Demonstrate that the directors cannot improve their outcome by changing the base salary in the profit-

sharing plan. What is the minimum share of the firm’s profit that will induce the CEO to expend high effort?

You have decided to produce a line of moisture-

wicking skateboarding clothes. You’re a wonderful designer, but a lousy tailor, and as a result, you decide to hire your roommate (who is a wonderful seamstress) to produce the clothes for you. Is it better for you to pay your roommate by the hour or to pay by the garment? Explain. Princess Buttercup has a multitude of potential suitors. She wishes to separate them into two groups—

those who are truly interested in her hand in marriage, and those who are only interested because she’s convenient, pretty, and rich. Let’s call these two groups “interested” and “nonchalant,” respectively. In an attempt to separate the two groups, Princess Buttercup devises a plan under which potential suitors must slay dragons before coming to the castle to court her. Those who slay the requisite number of dragons,

, will be allowed to court her.

, will be allowed to court her.Those who do not slay the requisite number of dragons will only be allowed to court Princess Buttercup’s ugly half-

sister, Princess Poison Ivy. To a member of either group, the benefit to courting Princess Buttercup is equal to $1,000.

To a member of either group, the benefit to courting Princess Poison Ivy is $64.

To a member of the “interested” group, who pursue their goal with unbridled passion, the cost of passing Princess Buttercup’s test is given as D2, where D is the number of dragons slain.

To a member of the “nonchalant” group, who pursue their goal halfheartedly, the cost of passing Princess Buttercup’s test is given as D3, where D is the number of dragons slain.

Princess Buttercup wants to sort the interested suitors from the nonchalant suitors. What is the minimum number of dragons Princess Buttercup can ask potential suitors to slay if she wants them to separate into groups? (You can round to an appropriate integer.)

Suppose that Princess Buttercup asks suitors to slay three fewer dragons than you indicated in your answer to (a). Why will asking suitors to slay this many dragons not help Princess Buttercup filter out the nonchalant suitors?

What is the maximum number of dragons Princess Buttercup can ask potential suitors to slay if she wants to be able to distinguish between interested and nonchalant suitors? (Again, you may round your answer to an appropriate integer.)

Suppose that Princess Buttercup asks potential suitors to slay three more dragons than you indicated in your answer to (c). Why will asking suitors to slay this many dragons not help Princess Buttercup filter out the nonchalant suitors?

Suppose that Princess Buttercup has appropriately set the number of dragons, filtered out the nonchalant suitors, and chosen her prince from the pool of interested suitors. Now, she wishes to see if her prince wants her because of love, or whether her prince is only interested given her vast fortune. What modern American legal device might Princess Buttercup use as a screening tactic to discover the true answer? Explain your response.

650

Suppose that there are two types of workers in the world: Charlie Hustles, who are high-

productivity workers, and Lazy Susans, who are low- productivity workers. The market would pay $70,000 (this and all numbers in this question are in present value terms) to hire a Charlie Hustle, but only $20,000 to hire a Lazy Susan. The problem, of course, is that a firm cannot tell on sight whether a job applicant is a Charlie or a Susan. One way to attempt to separate the Chucks and the Suzies is to require a college degree. It is easy for a Charlie Hustle to obtain a degree (the degree takes four years to complete and costs $40,000 in total). It is harder for a Lazy Susan to obtain a degree (six years and a cost of $60,000). Assume that a college education adds nothing to either worker’s productivity. If the company, operating blindly with no degree requirements, were to pay an average wage of $45,000, what would most of its applicants look like?

If the company were to pay an average wage of $45,000, most of its applicants would look like Lazy Susan.

Suppose that the company announces that it will pay $70,000 to those with college degrees, and $20,000 to those without. What is the net benefit of a college education to a Charlie? To a Susan? Does the degree requirement allow the firm to filter out low-

quality applicants? The market is willing to pay $70,000 to those who signal ability through a college degree. Otherwise, the pay offered will be $20,000 now that this requirement is in place. Thus, the net benefit of obtaining a degree is the $50,000 difference minus the cost of a degree. For Charlie Hustle, this difference is +$10,000 ($50K minus $40K). For Lazy Susan, the net benefit is –$10,000 ($50K minus $60K).

Therefore, the degree requirement does permit the firm to separate the two groups of applicants.

Suppose that a new federal subsidy to assist low-

productivity workers reduces the cost of obtaining a degree to $46,000. What is the net benefit of a college education to a Charlie? To a Susan? Does the degree requirement allow the firm to filter out low- quality applicants? The net benefit to a college education to a Charlie remains unchanged, whereas the net benefit to a Susan now becomes $50,000 – $46,000 = $4,000. In this case, the net benefit for both types of applicants is positive. Therefore, the degree requirement is not sufficient anymore to allow the firm to filter out low-

quality applicants. In light of your answers to (b) and (c), discuss the following assertion: To be effective, a signal must be costly, but it must be more costly for a low-

productivity applicant.The assertion is correct. Obtaining the signal to low-

productivity applicants must be more costly; otherwise, the filtering will not be possible. Colleges and universities have been accused of practicing grade inflation. In fact, some colleges have actually outlawed awarding a grade of “F.” Given your answer to (d), discuss the impact of this practice on the signaling value of a college diploma. Is this practice good for students? Does your answer depend on the quality of the student? Explain.

Grade inflation is definitely a bad practice for students as it bridges the qualitative differences among students in a way that makes it almost impossible to differentiate the level and potential of students. A B or a B+ student who is pushed in the A range prevents the appropriate sorting and inhibits the efficient functioning of merit. This is bad for high-

quality students who would like to distinguish themselves. It also is bad for both types of students because this signal then becomes an “arms race” (as explained in the chapter) of who will be able to (get into and) graduate from the most prestigious (most expensive) institutions of higher learning.

Peacocks, with their fabulous tails, live wild in the jungle. There, a tail is a detriment—

it slows the birds in flight, and presents an excellent handle for a predator to grab hold of. Nevertheless, males continue to grow them because peahens love bling, and the more, the better. Explain the value of a long tail as a signal, focusing on the general principle that signals must be costly to a strong bird, but even more costly to a weak bird.

The signal is costly to both types of birds because it represents an expense in terms of being slower in flight and thus susceptible to predators. However, it is even more expensive to a weak bird given that he is already more likely to fall victim to a predator’s attack.

Peahens would receive the same information if all peacocks cut their tails in half. In light of this truth, explain why the signal is socially costly.

If the same signal could be achieved at a lower cost (represented by the lower danger of being caught by predators when the tails are half as long), then any growing of tails longer than that is just a waste of resources from society’s point of view.

Suppose all male peacocks agreed to cut their tails in half. Explain why such an agreement is unlikely to last, and why the disintegration of the agreement makes all peacocks worse off.

Such agreement is unlikely to last as peacocks have an incentive to cheat and grow their tails in order to signal greater attractiveness to peahens. Therefore, the scheme would break apart, which would result in peacocks growing their tails long. Such a signal would be costly as peacocks would be slower in flight and more susceptible to predators.

In the late 1800s “wildcat banks,” which were easy to charter and largely unregulated, sprang up across the American West. Some new banks chose to operate out of simple and inexpensive wooden structures, but others built elaborate buildings out of stone, with lots of gilding and other adornment.

Explain how the variety of building types that sprung up can be attributed, at least in part, to the potential for moral hazard.

Explain how the building choices of bankers in late 1800s America illustrate the inherent wastefulness of signaling.