16.2 Moral Hazard

moral hazard

A situation that arises when one party in an economic transaction cannot observe the other party’s behavior.

Another information asymmetry that can cause problems in markets is moral hazard, which exists when the information gap involves the inability of one party in an economic transaction to observe another party’s behavior. That last word—

A stark example of a moral hazard problem is fraud. Suppose you pay a mechanic to fix a problem with your car, and he pockets the money without making any repairs, hoping that you will be unable to detect this. He’s relying on the fact that his action is unobservable. If you either literally cannot see whether the work has been done—

Fraud aside, numerous moral hazard situations are less malicious but still potentially damaging to markets. Insurance markets again offer many such cases. We talked about adverse selection in insurance, which deals with the unobservable riskiness of people seeking insurance coverage. Moral hazard is different. Moral hazard has to do with the effect insurance coverage has on individuals’ behaviors once they have it: specifically, that they will make fewer efforts to avoid having to make claims once they are already covered. Moral hazard is therefore a concern to insurers after a policy has been purchased.

628

An Extreme Example of Moral Hazard

An example will make this clear. (It’s slightly ridiculous in order to exaggerate the point.) Suppose movie producers could buy “box office insurance” that guaranteed them a specified gross revenue for a particular film if box office receipts did not reach this level. Producers wanting more coverage—

Such policies could be very valuable economically. Movie revenues are unpredictable. Producers might prefer to have a more certain income flow for planning purposes among many other reasons, and risky movies tend not to get made. Insurance companies could find selling such policies appealing in principle as well: If the insurers spread their risk over enough movies, they could earn enough premium revenue from the successful movies that didn’t need to cash in their policies to both pay claims on disappointing movies and make a profit.

The adverse selection problem is that producers of lower-

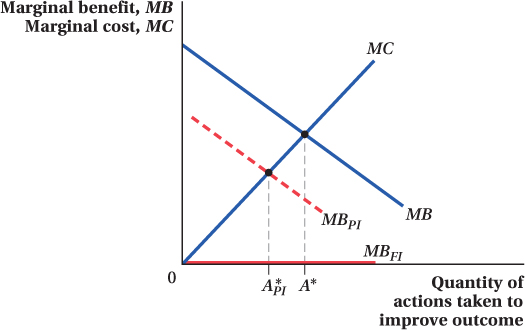

Again, this is a somewhat absurd example to make a point, but these forces operate in many markets. Figure 16.1 shows one way to think about how moral hazard works more generally. This figure plots a potential policyholder’s marginal benefit and the marginal cost of taking actions that increase the chance of a “good” outcome occurring.

What we mean by “good” outcomes depends on the particular situation. This could include a movie doing well at the box office, a driver not getting in an accident, a person not falling into ill health, and so on. Importantly, however, actions that raise the likelihood of such good outcomes are not costless to the potential policyholder. Those actions may involve financial cost, such as hiring a decent cast and crew and designing a solid marketing plan for a movie, and almost always involve effort, such as driving with care and resisting the temptation to text friends while behind the wheel, and eating well and exercising regularly. The cost in terms of money and effort of taking a bit more of these sorts of actions is shown in Figure 16.1 as marginal cost MC. We assume this marginal cost rises with the amount of actions already taken. This assumption is realistic; making initial efforts to put together a decent movie or to not drive recklessly is probably not too difficult and thus not too costly, but after having implemented the easier actions, taking further actions to improve outcomes becomes increasingly arduous and costly.

629

The benefit of such actions is the gain that the potential policyholder obtains when a good outcome occurs. Thus, the marginal benefit of the actions is the incremental increase in the good outcome (or the probability of the outcome) that taking further action creates. In Figure 16.1, these marginal benefits are shown as MB. We assume they decrease as the amount of action taken increases, because it’s likely that the actions taken to create a good outcome have diminishing returns.

In a market with no insurance, the potential policyholder would take actions up to point A*. Here, his marginal benefit of taking further action just equals his marginal cost of doing so; taking any more or less action than this level would only reduce his net benefit. Action levels less than A* would decrease his expected benefit more than it saves him in cost. Actions beyond A* would cost more than they are worth in benefit.

Now suppose he obtains insurance against bad outcomes. If the movie is a flop, he gets in a car accident, or needs medical care due to unhealthy behavior, the policy will kick in. If the policy offers full insurance—that is, the policy pays off enough so that the policyholder is just as well off as he would have been had the good outcome occurred instead of the bad one—

Even without full insurance, the existence of a policy that pays off in case of a bad outcome will reduce the policyholder’s marginal benefit of taking actions to make good outcomes more likely—

These cases exemplify the moral hazard problem in insurance: Being insured against a bad outcome actually leads the insured party to act (or not act) in ways that increase the probability of the bad outcome. If the loss associated with having a low-

630

The role of information asymmetries in the moral hazard problem involves the insurer’s inability to observe and verify the actions of the policyholder. If the insurer could specify that the policyholder take certain actions and be able to observe that the policyholder follows through, moral hazard becomes less of a problem (more on this in the next section). An insurance company underwriting a movie’s box office receipts, for example, might specify certain production requirements: cast and crew members, minimum budget, running length, marketing expenditures, and so on. But as a practical matter, it is impossible to observe and verify every single action taken by a producer that affects a movie’s revenue. Thus, there will always be some moral hazard problem. Because such a large fraction of producers’ actions are unverifiable, the problem is so difficult that it would likely destroy the market for box office insurance altogether.

figure it out 16.2

Anastasia and Katherine own a café. Because of their equipment and business, they run a risk of loss due to small kitchen fires. This risk can be mitigated by taking precautions such as purchasing fire extinguishers or by increasing the training and awareness of the café’s employees. Assume that the marginal cost of these precautions can be represented by MC = 80 + 8A, where A is equal to the actions taken to mitigate the risk of a fire. Likewise, the marginal benefit of these precautions is MB = 100 – 2A.

If the café has no insurance, what would be the optimal level of precautions for Anastasia and Katherine to take?

Suppose the café has insurance that reduces the marginal benefit of taking precautions to MB = 90 – 4A. What happens to the optimal level of precautions? Explain why this is the case.

Solution:

With no insurance, the optimal level of precautionary actions would occur where MB = MC:

100 – 2A = 80 + 8A

10A = 20

A = 2

Once the insurance is in place, the marginal benefit of taking precautions falls to MB = 90 – 4A. The optimal level of precautions also falls:

MB = MC

90 – 4A = 80 + 8A

12A = 10

A = 0.83

The optimal level of precautionary actions falls when insurance is available. If a fire occurs, the café’s owners will experience a smaller loss as a result of the insurance coverage. Therefore, the owners’ incentives to try to prevent a loss are reduced.

Examples of Moral Hazard in Insurance Markets

Wrecked markets aside, moral hazard is still an issue in existing insurance markets. Many have argued that the United States’ National Flood Insurance Program encourages homeowners to build—

631

Auto insurers are always concerned about their policyholders’ unobserved driving habits. Insurance is usually priced by the period (per six-

Unemployment insurance, while offering some financial relief to workers who have lost their jobs by partially replacing their lost wages, can also reduce unemployed individuals’ incentives to look for work. While unemployment benefits are tied to the recipient actively looking for work, the agencies that administer the program cannot fully observe recipients’ true efforts to find employment. The intensity of the job search and the individual’s effort in interviews are difficult to monitor.

Moral Hazard outside Insurance Markets

Moral hazard problems aren’t restricted to insurance markets. They arise between lenders and borrowers in financial markets, too. Lenders often loan funds to borrowers to use for a particular purpose. Suppose a borrower asks for a loan to invest in new equipment for a business. Once he has the money, however, he may find expenditures on other items more appealing. Perhaps he would like some fancy antique furniture for his office. If the borrower uses the loan for the antiques and then skimps on equipment, and the lender can’t fully observe how the funds are used, there is moral hazard. By spending part of the loan on unproductive antiques and shortchanging expenditures on productive capital, the borrower reduces the probability that he will be able to repay the loan. This is bad news for the lender and it results from the lender’s inability to observe exactly how the borrower uses the loaned funds.

Discussions about policy responses to the financial crisis of 2008 have involved moral hazard concerns. Governments around the world have bailed out banks and other financial institutions in an effort to stave off a collapse of the financial system. There is concern, however, that such policies could backfire by encouraging overly risky behavior by banks in the future. This criticism is based on moral hazard arguments. Specifically, a bailout keeps institutions that played too fast and loose in the run-

632

Unobserved actions play an important role in labor markets, too. Employers cannot typically observe all the actions of their employees. Employees may wish to engage in work-

Lessening Moral Hazard

Just as with adverse selection and the lemons problem, many market mechanisms have developed to reduce moral hazard. One possibility for insurance markets that we hinted at above is the insurer’s specifying certain actions that must be taken by the policyholder as a condition of coverage. This is often followed up by the insurer verifying that the actions have, in fact, been taken. For example, commercial property insurance companies may require smoke detectors and firefighting equipment to be installed and maintained in buildings they insure. These insurers may then send inspectors to verify compliance with such regulations. Many life insurance policies include an exemption from paying benefits if the policyholder commits suicide.

These approaches seek to head off moral hazard problems directly, by specifying and monitoring what the policyholder does. That is, these methods recognize that while the actions of the policyholder might not be perfectly observable, key behaviors that greatly impact the insurer’s payoff can be specified by contract (assuming that the insurer maintains the ability to monitor and verify the policyholder’s actions).

A related approach is for insurers to structure policy contracts to give policyholders incentives to take actions that reduce risk. Homeowners typically get a break on their policies if they install smoke detectors, dead-

Deductibles are the portion of claims that the policyholder must pay out of his own pocket. A person with a $500 deductible on his auto insurance who causes an accident leading to damage of $5,000 will only obtain $4,500 from the insurer for repairs. By imposing some cost of claims directly on the policyholder, the insurer gives him an incentive to take actions that reduce the likelihood of claims. Copayments work similarly. These are payments (most commonly applied in health insurance markets) that the policyholder must dole out whenever making a claim. A $5 fee you have to pay for each prescription you obtain through a prescription drug plan, for example, is a common type of copayment. In co-

These and other practices reduce the impact of moral hazard on insurance markets, preserving much of the economic gains from their existence. It’s important to remember, however, that even when damped by these institutions, moral hazard can still affect the structure of the markets in which it is a factor.

633

Application: Usage-Based Auto Insurance

As we discussed above, the typical structure of car insurance policies leads to moral hazard problems. Insurance is priced by the time period, and premiums are weakly (if at all) related to the actual intensity or riskiness of driving within the coverage period. Policyholders therefore don’t fully pay for the extra risk their insurers bear when they drive many miles or drive aggressively. As a result, they have too little incentive to reduce risk.

The solution to this problem is conceptually clear: Insurers should monitor their policyholders’ actual driving behavior and adjust premiums based on the observed actions. Particularly heavy or risky driving during the coverage period should cost more.

This solution has not been widely implemented, however, because of the practical difficulties in monitoring drivers’ habits. It would be impossibly expensive for your auto insurer to, for example, pay a monitor to sit in your back seat and record your routines as you drove around.

Things may be changing, though. Technological advances have reduced the barriers to such monitoring. Small electronic devices that interface directly with cars’ onboard computers can now gather data on miles driven, acceleration and deceleration rates, and the times of day at which the wheels were rolling. Auto insurers have started to experiment with these technologies. U.S. insurer Progressive has the Snapshot program, which lets participating drivers earn discounts off the standard premium if they drive fewer miles at the right times of day or if they can reduce hard accelerations and stops. The program is available in all but five states and offers discounts of up to 30% for low-

Such policies, called usage-