16.3 Asymmetric Information in Principal–Agent Relationships

principal–

Economic transactions that feature information asymmetry between a principal and his hired agent, whose actions the principal cannot fully observe.

Principal–

634

There are many, many examples of principal–

The divergence in an employer’s preferences (let’s call our employer Yvonne) and those of her employee (let’s call her Jean) is not in and of itself a problem. The two could write an employment contract with Jean’s pay contingent on her completing a set of tasks or conveying certain information specified by Yvonne. Jean would then have strong incentives to do as Yvonne wished, and Yvonne would have to compensate Jean enough for her to be willing to complete the requested actions. The problem lies in the fact that, because of the information asymmetry, the principal (Yvonne) can’t ever know for sure if the agent (Jean) has done what she requested. Yvonne must instead infer the adequacy of Jean’s responses as best as she can, using only imperfect information about Jean’s job performance. For example, Yvonne can’t just observe sales and know exactly how hard Jean worked. Maybe Jean didn’t work hard, but other things caused sales to be high. Or, maybe Jean did work hard but other factors caused sales to be low. Yvonne can’t know for sure. While sales are likely to be correlated with Jean’s effort, they are also influenced by unrelated factors. This makes sales an imperfect measure for Yvonne to gauge Jean’s actual level of effort.

This logic carries over to other types of principal–

The moral hazard problems facing insurers and their policyholders can also be cast as principal–

What can the principals do in these situations? The principals know how they would like their agents to act. The problem is that the principals cannot fully observe what the agents do. Otherwise, the principals could simply make the agents’ payoffs conditional on taking the desired actions. Instead, the principals must somehow set up incentives to make it in the agents’ own best interests to take the actions that the principals desire.

Principal–Agent and Moral Hazard: An Example

Let’s consider a simple example. Suppose that the daily profit of a small mobile phone kiosk in the local mall is higher when the kiosk’s employee, Joe, works harder. (We’ll assume for simplicity that Joe is the only employee.) Joe can work hard, in which case the kiosk’s daily profit is $1,000 with 80% probability and $500 with 20% probability. (The latter might happen if it rains so traffic at the mall falls.) Alternatively, Joe could laze about by staring blankly at passersby and texting his friends. If Joe does so, the probability of the kiosk’s profit will be reversed: There will be 20% probability of a profit of $1,000 and 80% probability of $500. Joe doesn’t like to work hard; he has to be paid at least $150 before he’s willing to do so. Otherwise, he’s going to text his friends all day.

How should the kiosk’s owner (Selena, the principal) structure Joe’s (the agent’s) compensation? Remember, the root of the principal–

635

When Joe’s effort is unobservable, however, his pay cannot be based on how hard he works. And, simply offering Joe a flat wage of $150 isn’t a solution either. Because he faces a cost of working hard but would take home the same pay regardless of whether he exerts any effort, he would choose to be lazy. This is clearly undesirable to Selena, who would pay $150 in wages but only earn the low expected profit of $600 rather than $900. When effort is unobservable, therefore, simply offering enough pay to compensate Joe for his effort does not actually lead to him working hard.

What Selena can do, however, is tie Joe’s pay to something she knows is related to Joe’s effort: namely, the kiosk’s profit. Because Joe can affect the likelihood that profits (and therefore his wages) are high by working hard, this offers him an incentive to exert effort. Of course, the extra wages he expects to earn working hard have to be high enough to compensate him for that extra effort.

Suppose Selena offers the following deal: Joe is paid $255 if the kiosk’s profits are high (i.e., $1,000) and $0 if profits are low ($500). What sort of behavior would this lead to? Think about Joe’s tradeoffs. If he works hard, he has an 80% chance of earning $255 and a 20% chance of earning nothing. His expected earnings are $204 (0.8 × 255 + 0.2 × 0). However, he also suffers an effort cost of $150, so his net gain from working hard is $54. If Joe chooses to be lazy, he will have an 80% chance of earning nothing and a 20% chance of earning $255, yielding expected earnings of $51. By being lazy, Joe pays no effort cost, so his net gain from being lazy is $51. Under this compensation plan, Joe prefers working hard to being lazy.

Does Selena also prefer this new plan? We already know that if Joe works hard, the kiosk’s expected profit will be $300 higher. Selena expects to pay Joe $204 (0.8 × 255 + 0.2 × 0) if he works hard. Thus, the new compensation scheme is worthwhile from Selena’s perspective, because by giving Joe the incentive to work hard, it raises her expected profit net of wages by $96.

Selena (the principal) can, in fact, give Joe (the agent) incentives to work hard. The key is to pay him much more when observable events occur that are correlated with his unobservable effort (i.e., when profit is high because Joe works hard). By tying the agent’s compensation to outcomes that the principal likes, the principal aligns the agent’s incentives on the margin with her own.

The Principal–Agent Relationship as a Game

This example, as with more general principal–

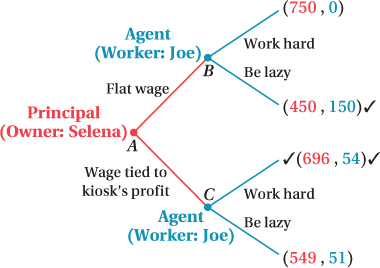

Figure 16.2 shows the game tree for the interaction between the mobile phone kiosk owner, Selena, and her employee, Joe. Selena moves first; she has the choice of paying Joe a flat wage of $150 that doesn’t depend on the kiosk’s profit or a wage that is tied to the kiosk’s profit: $255 if profit is high and $0 if it is low. Once the compensation structure is chosen, Joe then chooses his effort level: high or low. Given this choice, Selena and Joe earn their expected payoffs.

636

As with any sequential game, we can find the equilibrium using backward induction. Suppose Selena chooses the flat $150 pay structure. If Joe works hard, Selena’s expected payoff is $750 (the $900 profit from the kiosk minus the $150 wage she pays Joe), and Joe’s payoff is $0 (his $150 wage minus his $150 effort cost of working hard). If Joe chooses to be lazy, Selena’s expected payoff is $450 ($600 kiosk profit minus wages of $150), while Joe’s payoff is $150 (his wage alone, because he has no cost of effort). Selena prefers Joe to work hard, but Joe’s payoff is greater from being lazy. As a result, Joe chooses to be lazy under this compensation plan.

Now suppose Selena chooses to link Joe’s pay to the kiosk’s profit: Joe receives $255 for high profit and $0 for low profit. Joe works hard in this case, Selena’s expected payoff is $696 ($900 in expected kiosk profit minus the expected $204 in pay to Joe), and Joe’s expected payoff is $54 (his $204 expected wage minus his $150 effort cost of working hard). If Joe chooses to be lazy, Selena’s expected payoff is $549 ($600 kiosk profit minus wages of $51), while Joe’s expected payoff is $51. Joe’s expected payoff from working hard is higher in this scenario, so he makes the extra effort and raises the kiosk’s expected profit.

Now that we’ve solved for the last stage of the game, we can figure out Selena’s equilibrium action in the first stage. If she chooses the flat $150 pay structure, Joe doesn’t work hard and her expected payoff is $450. If Selena chooses to link pay to the kiosk’s performance ($255 for high profit and $0 for low profit), then Joe works hard and her expected payoff is $696. Therefore, Selena’s optimal action in the first stage is to choose the performance-

That’s the equilibrium of this principal–

Again, what Selena would really prefer is to monitor Joe’s effort directly, specify that he works hard as a condition of employment, and pay a flat wage of $150 to compensate Joe for working hard. In this case, Selena’s expected payoff would be $750, higher than in the equilibrium above. Selena can’t do this, however, because she is unable to continuously monitor Joe’s effort. As a result of the principal–

637

More General Principal–Agent Relationships

The Selena–

You might wonder, if principal–

Application: The Principal–Agent Problem in Residential Real Estate Transactions

Home sellers face an asymmetric information problem when they hire a real estate agent. An agent typically knows more about the state of the housing market than does a home seller. Indeed, the agent’s extra information is one of the reasons why people want to hire a real estate agent.

In addition to this information gap, contracts in the industry typically give agents very weak marginal incentives to get the highest price for the houses they sell. Most agents are paid a commission that is a small fraction of the selling price of the home. Typically, the total commission on a sale is around 6%, but after the buyer’s agent and the brokerage for which the agent works receive their shares of the commission, the seller’s agent takes home only about 1.5% of the sales price.

You might think that having compensation tied to the outcome the seller would desire (a higher sales price) fits the optimal principal–

The combination of the information gap and the misaligned incentives can create distortions, as two of this book’s authors (Steven Levitt and Chad Syverson) point out in their study of real estate transactions.9 Because agents bear much of the cost of selling a house (hosting open houses, buying ads, showing the home to potential buyers, etc.), but gain much less from a higher price, the agents have an incentive to convince the homeowner to sell faster at a lower price. For example, while most homeowners would wait two extra weeks if they could get an offer that is $10,000 higher (that’s worth an extra $9,400 to the sellers), agents may not be willing to pay two extra weeks’ worth of selling costs for an incremental commission increase of only $150. And, because sellers know less than agents about the likely offers forthcoming on their houses, sellers are susceptible to being convinced to quickly accept a lower offer.

The test of this theory compares house-

The results confirm the predictions above. When real estate agents sell their own houses, they keep their homes on the market longer and sell them for a higher price than comparable non-

638

figure it out 16.3

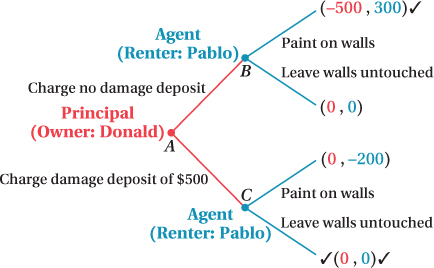

Pablo is a struggling artist who wants to rent an apartment from Donald. Pablo loves to draw, so much so that he often draws on any surface he can find, including walls. In fact, Pablo would get $300 in utility from being able to draw his artwork on the walls in his apartment. On the other hand, Donald would like Pablo to leave the apartment walls clean and free of any marks. If Pablo draws his art on the walls, it will cost Donald $500 to have the apartment repainted. Therefore, Donald is considering charging Pablo a damage deposit of $500.

Explain why this situation could be considered a principal–

agent problem. Who is the principal? Who is the agent? Draw the extensive form of this principal–

agent problem and use backward induction to solve for the Nash equilibrium.

Solution:

Donald is the principal and Pablo is the agent. Donald would like Pablo to treat the apartment the same way he (Donald) would. However, Donald cannot be at the apartment to monitor Pablo’s behavior all of the time. Therefore, a principal–

agent problem exists. Donald’s and Pablo’s interests do not coincide. The extensive form of this principal–

agent problem is shown in the illustration below. We can use backward induction to solve the game. If no damage deposit is charged, Pablo will want to paint on the walls because $300 > $0. If Donald charges a damage deposit, Pablo will leave the walls untouched because $0 > –$200. Given this information, we can see that Donald will charge the $500 damage deposit (because $0 > –$500). Thus, the Nash equilibrium is that Donald will charge the $500 damage deposit and Pablo will leave the walls untouched.

639