16.4 Signaling to Solve Asymmetric Information Problems

We talked earlier in the chapter about ways that sellers of high-

signaling

A solution to the problem of asymmetric information in which the knowledgeable party alerts the other party to an unobservable characteristic of the good.

It turns out this basic idea applies across many economic settings, enough, in fact, to have its own name: signaling. Signaling lets one party in a transaction communicate to another party something that is otherwise not immediately observable. It’s one way in which asymmetric information problems can be solved in markets.

Signaling was first formalized by economist Michael Spence in the early 1970s and he won the Nobel Prize for it.10 The basic idea of signaling is that there is some action, the “signal,” that conveys otherwise unknown information about the signal sender. For the signal to be meaningful—

The Classic Signaling Example: Education

Signaling can have surprisingly powerful effects. Even if a signal is inherently worthless—

640

Suppose that going to college does absolutely nothing to improve your productivity on a job. (This is not what labor economists who have studied the issue have found, but it will show how powerful signaling can be.) Let’s assume that productivity is a function of personal organization, perseverance, and the ability to concentrate and learn new things quickly. Employers would like to find workers with these qualities. They want to hire productive workers and pay them more. But, the problem of asymmetric information gets in the way. Employers cannot tell from an interview and résumé if a potential employee has these characteristics.

Highly productive workers would like to convince potential employers they would be good hires. But, applicants can’t just say, “Hey, I’m very productive.” That’s cheap talk. Less productive workers will say the same thing. Productive workers need some sort of “expensive talk” instead.

signal

A costly action taken by an economic actor to indicate something that would otherwise be difficult to observe.

That’s what a college degree offers. Why? College is costly, and, importantly, it’s more costly for some than others. It’s costly in a monetary sense, but also in the sense that it takes a lot of effort. To be able to expend the necessary effort, a student has to have certain qualities, like being organized, a willingness to persevere, and the ability to concentrate. The very same attributes that make a worker productive also make it easier for him to finish college. College is hard, but people without those attributes find it extremely hard. If you are a productive worker, therefore, a good way to demonstrate this to employers is by completing a college degree. You have made a costly choice that indicates something about your qualities that would otherwise be difficult to observe. That is, you have sent a signal. Here, the signal is aimed at employers with the intent of demonstrating your productivity.

The signal in this example won’t be meaningful if unproductive workers also receive college degrees. Employers can’t distinguish between high-

When more productive workers finish college and less productive workers don’t, employers can tell the difference between them. These employers are willing to pay the college graduates more, because they are more productive. We end up with the empirical fact we talked about earlier: College graduates earn more pay, even if they didn’t learn a thing in school.

Signaling: A Mathematical Approach Let’s use some specific numbers to make this result clearer. Suppose there are two types of workers, high-

CH = $25,000y

CL = $50,000y

where y is years in college, and CH and CL are the costs of attending school for high-

Let’s suppose that, over the course of a worker’s lifetime, a high-

641

To be willing to pay high-

Do only high-

CH = $25,000y = $25,000 × 4 = $100,000

Low-

CL = $50,000y = $50,000 × 4 = $200,000

The benefit to each worker of finishing college is actually the same. Employers pay a total premium of B = $125,000 in wages for completion of a college degree. Remember, because employers can’t tell directly how productive a worker is, they are trying to rely on college completion to make the distinction.

Therefore, the net benefit (NB) to completing college for high-

NBH = B – CH = $125,000 – $100,000 = $25,000

while for low-

NBL = B – CL = $125,000 – $200,000 = –$75,000

High-

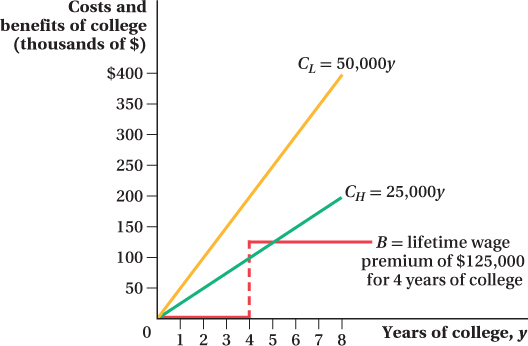

Signaling: A Graphical Approach With this example, we’ve shown that the employers’ strategy makes sense. They pay a wage premium to college graduates on the expectation that they will be high-

This outcome can be seen in Figure 16.3, which shows workers’ costs and benefits of college as a function of the number of years in college. Low-

For low-

642

This example demonstrates the potential power of signaling. Here, something that has no real benefit to society (because we assumed education does not enhance worker productivity) actually determines how much income each worker earns. The productive workers pay to go to college, but society gets nothing economically useful in return. A college degree doesn’t make these workers more productive, because they were already more productive before attending college. Yet, using a degree as a signal allows productive workers to indicate their productivity to employers, so these workers are paid more. However, four years of college is a rather expensive signal! If these workers could somehow find a cheaper way to signal their greater productivity, society would be better off.

Economists sometimes use “money burning” as a shorthand phrase to refer to the wasteful expenditure of resources for the purposes of sending a signal. In fact, literally burning money can itself be a signal in some cases. Suppose wealth were imperfectly observable (perhaps it’s difficult to show people all your assets at once or to convince them of their value), and that a person wished to signal his wealth to another. He could do so by starting a cash bonfire. While burning money is obviously costly, it is less costly—

Education and Productivity As we said, economists have found a lot of evidence that, in reality, college (and more years of education in general) does have positive effects on actual on-

643

This sheepskin effect has shaped the recent debate about college costs and whether the actual productivity benefits of higher education are overstated. After all, if tuition levels double not because college has actually made graduates more productive but instead because students are trying harder to signal their abilities by going to highly regarded (and more expensive) colleges, this situation is like an arms race among students, that is, a situation where competitors just try to stay ahead of their competition without any real improvement in rank. (The term is often used in military discussions as countries manufacture or purchase more and more weapons to try to stay ahead of one another.) In this example, students are spending large amounts of resources without any real change in their job market prospects because they’re sending the same signal as before, but it’s now more expensive. In addition, the increased spending does not provide any additional benefits to society in the form of more productive workers.

The evidence also suggests, however, that signaling effects are largest right after a worker is hired and quickly disappear thereafter. This isn’t surprising; after employees work for a while, firms can directly observe their actual productivities. The employees’ wages respond in turn. More productive workers—

To sum up, there are two reasons why schooling is important and increases wages: (1) because it raises productivity and (2) because it works as a signal that the person is more productive. While both matter in the labor market, the evidence suggests that Reason 1 plays a bigger role in explaining the relationship between income and schooling than does Reason 2.

Other Signals

Signaling is present in all sorts of economic situations beyond our example. As we mentioned earlier, for instance, warranties signal that a good is of high quality.

Buying an engagement ring for a fiancée can signal one’s commitment to getting married. If, as sometimes happens, the woman keeps the ring should the wedding be called off, only men expecting the wedding to occur will be willing to pay for the ring. The ring, as with attending college and offering warranties, allows men to substitute “expensive talk” regarding their (imperfectly observed) true feelings for what would otherwise be cheap talk.

The choices people make about the products they use or the ways in which they live their lives can be signals. They may want to inform family, friends, neighbors, or even strangers about some aspect of their personalities that would otherwise be difficult to convey. Some monks take vows of poverty. This, in part, signals their devotion. Dressing up to go to work can be a signal of one’s commitment to and seriousness about a job. Consumption patterns can be used to signal income or wealth to one’s social network.

These examples only scratch the surface of the wide span of signaling that occurs in our society. They also indicate both the frequency of asymmetric information in economic interactions as well as the power signaling can have to reduce it.

644

Application: Advertising as a Signal of Quality

Firms use advertising to send all kinds of messages about their products: newer, cheaper, cooler—

The argument for advertising as a signal goes something like this. Advertising is costly, but it’s really costly for unsuccessful, unprofitable companies. Why would a company be unsuccessful? Because it makes products that consumers don’t like. So, the only firms that can afford to advertise are those that make things that consumers want to buy. By advertising, companies are effectively saying to consumers, “Our product is so excellent and will make us so much profit that we can afford to spend all this money advertising it. Companies that make lousy products aren’t able to do that.” All that’s needed for this signaling effect to work is for the company to spend money on advertising. The ad doesn’t need to offer any particular information at all about the product.

Perhaps one of the best examples of an “all-

The ad was widely considered to be a success. Evidently millions of people thought, “That must be some kind of trading firm if they can afford to waste their money on Super Bowl ads like that.” Signal sent; signal received.

figure it out 16.4

Last year, Used Cars “R” Us sold very few cars and ended up with a large economic loss. The owner, Geoffrey, has developed two strategies to help the dealership sell more vehicles in the coming year by signaling that it deals in only high-

Change the name of the dealership to Quality Used Cars “R” Us.

Offer a 60-

day bumper- to- bumper warranty for every car sold.

Which of these two strategies is the best signal of high quality? Explain.

Solution:

To be a good signal of quality, a signal must be cheaper for high-

The change of the name of the dealership would just be “cheap talk.” Any dealership can alter its name, and the cost of doing so will not vary across high-

645