2.1 Markets and Models

Modern economies are amazingly complex. Producers from all over the world offer a nearly unlimited variety of goods and services that consumers can choose to purchase. A large supermarket will have more than 100 different kinds of cold cereal on the shelf. There are thousands of degree-

12

Answering these questions might seem like a hopelessly complex task. Indeed, if we tried to tackle them all at once, it would be hopeless. Instead, we follow the economist’s standard approach: Simplify the problem until it becomes manageable.

The supply and demand model represents the economist’s best attempt to capture many of the key elements of real-

What Is a Market?

The idea of a “market” is central to economics. What does it mean? In the strictest sense, a market is defined by the specific product being bought and sold (e.g., oranges or gold), a particular location (a mall, a city, or maybe the Internet), and a point in time (January 4, 2016). In principle, the buyers in a market should be able to find the sellers in that market, and vice versa, although it might take some work (what economists call “search costs”) to make that connection.

In practice, the kinds of markets we talk about tend to be broadly defined. They might be broader than above in terms of the product (e.g., fruit or groceries rather than oranges), the location (often we consider all of North America or even the world as the geographic market), or the time period (the year 2016 rather than a specific day). These broader markets are often of more interest and have more data to analyze, but as we will see, defining markets so broadly makes the assumptions of the supply and demand model less likely to hold. Thus, we face a tradeoff between studying small, less consequential markets that closely match the underlying assumptions and broader and more important markets that do not match the assumptions as well.

Now that we have defined a market, we are ready to tackle the key assumptions underlying the supply and demand model.

Key Assumptions of the Supply and Demand Model

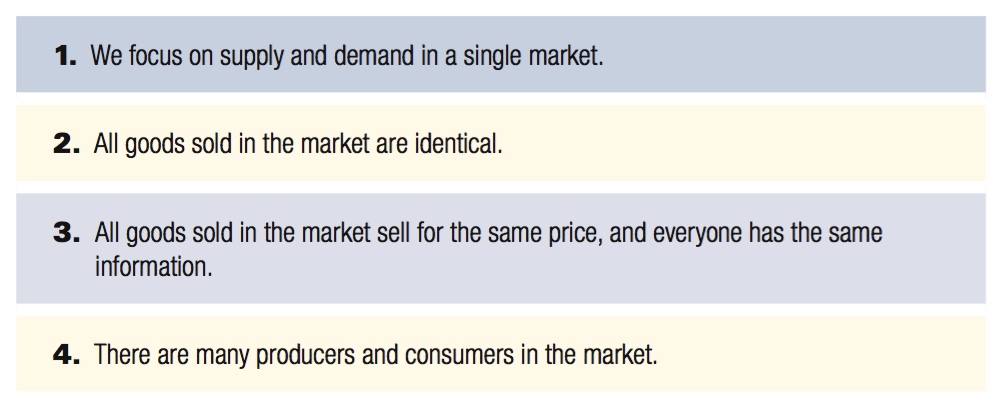

There are four basic assumptions that underpin our development of the supply and demand model. Table 2.1 summarizes these assumptions. Notice that the assumptions of the supply and demand model are in many cases unrealistic, and few of the markets you participate in satisfy all of them. It turns out, however, that a strength of this model is that when some (or even most) of the specific assumptions of the model fail, it still manages to provide a good description of how markets work. No model is perfect, but the supply and demand model has survived the test of time and is the workhorse of economics. Developing a deep understanding of the basic supply and demand model is one of the most important tools you can have as an economist, even if the model does not perfectly fit every market. Plus, economics isn’t completely wedded to the most stringent form of the model. Much of the rest of this book, and the field of economics more generally, are devoted to examining how changing the model’s assumptions influences its predictions about market outcomes.

supply

The combined amount of a good that all producers in a market are willing to sell.

demand

The combined amount of a good that all consumers in a market are willing to buy.

We restrict our focus to supply and demand in a single market. The first simplifying assumption we make is to look at how supply (the combined amount of a good that all producers in a market are willing to sell) and demand (the combined amount of a good that all consumers are willing to buy) interact in just one market to determine how much of a good or service is sold and at what price it is sold. In focusing on one market, we won’t ignore other markets completely—

indeed, the interaction between the markets for different kinds of products is fundamental to supply and demand. (We focus on these interactions in Chapter 15.) For now, however, we only worry about other markets if they influence the market we’re studying. In particular, we ignore the possibility that changes in the market we’re studying might affect other markets. 13

Figure 2.1: Table 2.1 The Four Key Assumptions Underlying the Supply and Demand Model

Figure 2.1: Table 2.1 The Four Key Assumptions Underlying the Supply and Demand ModelAll goods bought and sold in the market are identical. We assume that all the goods bought and sold in the market are homogeneous, meaning they are identical, so a consumer is just as happy with any one unit of the good (e.g., any gallon of gasoline).1

commodities

Products traded in markets in which consumers view different varieties of the good as essentially interchangeable.

The kinds of products that best reflect this assumption are commodities, goods that are traded in markets where consumers view different varieties of the good as essentially interchangeable. Goods such as wheat, soybeans, crude oil, nails, gold, or #2 pencils are commodities. Custom-

made jewelry, cars, the different offerings on a restaurant’s menu, and wedding dresses are not commodities because the consumer typically cares a lot about specific varieties of these goods. All goods sold in the market sell for the same price, and everyone has the same information about prices, the quality of the goods being sold, and so on. This assumption is a natural extension of the identical-

goods assumption, but it also implies that there are no special deals for particular buyers and no quantity discounts. In addition, everyone knows what everyone else is paying. There are many buyers and sellers in the market. This assumption means that no one consumer or producer has a noticeable impact on anything that occurs in the market and on the price level in particular.

This assumption also tends to be more easily justified for consumers than for producers. Think about your own consumption of bananas, for instance. If you were to stop eating bananas altogether, your decision would have almost no impact on the banana market as a whole. Likewise, if you thought you were potassium-

deprived and increased your banana consumption fourfold (because bananas are rich in potassium), your effect on the market quantity and price of bananas would still be negligible. On the producer side, however, most bananas (and many other products) are produced by a few big companies. It is more likely that decisions by these firms about how much to produce or what markets to enter will substantially affect market prices and quantities. We’re going to ignore that possibility for now and stick with the case of many sellers. Starting in Chapter 9, we analyze what happens in markets with one or a few sellers.

14

Having made these assumptions, let’s see how they help us understand how markets work, looking first at demand and then at supply.