7.2 Costs That Do Not Matter for Decision Making: Sunk Costs

Unlike opportunity costs, which a firm must always consider when making production decisions, there are some costs that should never be taken into account when making such decisions.

fixed cost

The cost of the firm’s fixed inputs, independent of the quantity of the firm’s output.

In Chapter 6, we learned that some of a firm’s costs are fixed costs, payments to inputs that must be used no matter what the output quantity is, even if it is zero. Suppose you own a restaurant. Some of your fixed costs would be rent (if you have signed a lease), cookware, advertising expenses, and kitchen appliances such as refrigerators and ovens. If you go out of business, even though you produce nothing, you still must pay those fixed costs. Of course, you might be able to recover some of these costs if you could sell the cookware and the ovens, or sublet the building to someone else. These refundable types of fixed costs are sometimes said to be avoidable because the firm can take action so that it does not have to pay them if it stops operating.

sunk cost

A cost that, once paid, the firm cannot recover.

Some fixed costs, however, are not avoidable. A fixed cost that you cannot avoid is called a sunk cost. Once a firm pays a sunk cost, it can never be recovered. For a restaurant, for example, money spent on advertising is a sunk cost. You spent the money, and there’s no getting it back. If you’ve signed a long-

To sum up: If a fixed cost is avoidable, then it is not a sunk cost. If a firm cannot recover an expense even when shut down, then it is a sunk cost. The difference between sunk cost and avoidable fixed cost is crucial to the decisions a firm makes about how it will react if things begin to go south and the firm suffers a downturn in its business.

One part of a firm’s cost that is sunk is the difference between what the firm still owes on its fixed capital inputs (such as the equipment and cookware at your restaurant) and what the firm can resell this capital for. This difference should be relatively small for restaurant equipment, because most of it can be easily used by other restaurants.

But suppose your restaurant had a space theme, with every booth shaped like the inside of a spaceship, with tables that look like control panels. Such booths, tables, and other items (menus, staff uniforms/spacesuits, etc.) tied specifically to your space-

251

specific capital

Capital that cannot be used outside of its original application.

As you can see from this last example, whether capital can be used by another firm is an important determinant of sunk costs. Capital that is not very useful outside of its original application is called specific capital. Expenditures on buildings or machines that are very specific to a firm’s operations are likely to be sunk, because the capital has little value in another use.

Sunk Costs and Decisions

An important lesson about sunk costs is that once they are paid, they should not affect current and future production decisions. The reason is simple: Because they are lost no matter what action is chosen next, they cannot affect the relative costs and benefits of current and future production decisions.

For example, you’ve no doubt attended an event like a concert, sporting event, or movie where you got bored well before the end. Should you stay just because you paid for the ticket? No. Once you are at the event, the ticket price is sunk—

operating revenue

The money a firm earns from selling its output.

operating cost

The cost a firm incurs in producing its output.

To put this in a production context, let’s go back to the restaurant example. You, as the owner, must decide between staying open for business or shutting down operations. Some of the restaurant’s costs are sunk costs, including nonavoidable fixed costs and the possible losses you would incur if you had to resell capital for less than you paid. These costs are not recoverable and must be paid whether the restaurant remains open or is shut down. In thinking about staying open for business, you know there will be some potential benefits (the money brought in from selling meals and drinks—

If business falls off, then, how should you decide whether to stay open for business or close the doors? Generally, the restaurant should stay open if the value of staying open is greater than the value of shutting down. But here’s the important part: Sunk costs should not enter into this decision. You are going to lose your sunk costs whether you keep the restaurant open or not, so they are irrelevant to your decision about your restaurant’s future. The choice between staying open and shutting down depends only on whether the firm’s expected revenues are greater than its expected operating costs. If it costs more to stay open than you’ll bring in, you should close the restaurant. It doesn’t matter if you are facing $1 or $1 million of sunk costs.

Application: Gym Memberships

“Should I stay or should I go?” applies to more than just a Clash concert, as economists Stefano DellaVigna and Ulrike Malmendier can attest to.1 They studied consumers’ actual behavior in buying—

252

What they found probably won’t surprise you: People are overly optimistic about how many times they’ll go to the gym. Members who bought a membership that allowed unlimited visits ended up going to the gym just over four times per month on average, making their average cost per visit about $17. They did this even though the gym offered 10-

People often buy these memberships with the hope that such behavior will induce them to go to the gym more often. The fact that people then don’t take full advantage of their memberships might, at first glance, seem like an irrational action. But the key point is that a gym membership is a sunk cost. In other words, when you’re sitting on the couch watching TV and debating whether you should go work out, you’re not going to consider how much you paid for your membership. It’s sunk, after all. You will, on the other hand, consider the opportunity cost of going to the gym—

sunk cost fallacy

The mistake of letting sunk costs affect forward-

The Sunk Cost Fallacy When faced with actual choices that involve sunk costs, people and firms sometimes have a difficult time ignoring sunk costs. They commit what economists call the sunk cost fallacy. The fallacy is that they act like sunk costs matter (when they should be ignoring them). In making economic, finance, and life decisions, you want to avoid falling victim to this fallacy, but it’s not hard to imagine scenarios where you might be tempted to do so.

How does it work? Suppose you are responsible for overseeing the construction of a new manufacturing facility for your company. Construction has gone on for 3 years and has cost $300 million so far (we’ll assume this entire expenditure is sunk—

You should stop the original project and start building the new factory. That’s because the $300 million (and the last 3 years) are sunk costs. They are lost whether you finish the first project or abandon it. The only comparison that should affect your decision, then, is between the relative benefits of finishing the first project and building an entirely new factory. Both will result in equally good production facilities in the same timeframe, but the new factory will cost only $40 million rather than the $50 million you would spend to complete the original factory. Thus, you should build the new factory. Despite this logic, many people would be reluctant to write off $300 million and 3 years of effort. The important point to realize is that the mere presence of this type of reluctance does not make it a good idea to give in to the temptation of the sunk cost fallacy.

Application: Why Do Film Studios Make Movies That They Know Will Lose Money?

The feature film industry is a multibillion dollar enterprise. Blockbuster movies like Guardians of the Galaxy or franchises like The Hunger Games and Star Wars drive the industry. A single major blockbuster movie can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, but there are no guarantees that people will like it enough to make back the costs. It is a risky business.

253

Sometimes while filming a movie, things go so wrong that the studio making the movie knows even before the film hits theaters that it will lose money. Yet, filmmakers often finish these movies and release them. Why they do this can be explained by the existence of sunk costs and their irrelevance to decision making.

One of the most infamous movie productions ever was Waterworld. You have probably never seen it—

Waterworld is set in a future in which the ice caps have melted and water covers the earth. Kevin Costner stars as the Mariner, a mutant who can breathe under water. His job is to protect (from the evil Smokers on Jet Skis) a young girl who has what may be a map of land tattooed on her back. The movie was filmed almost entirely on and under water.

Waterworld was released by Universal Studios in 1995, and at the time it was the most expensive movie ever made. By the end of production, costs totaled almost $175 million, even before marketing and distribution expenses, basically guaranteeing Universal a loss no matter how well the film was received. And it did lose money, grossing only $88 million in the United States and about twice that amount overseas. Because studios get to keep only about half of total ticket sales, experts presume it flopped terribly.

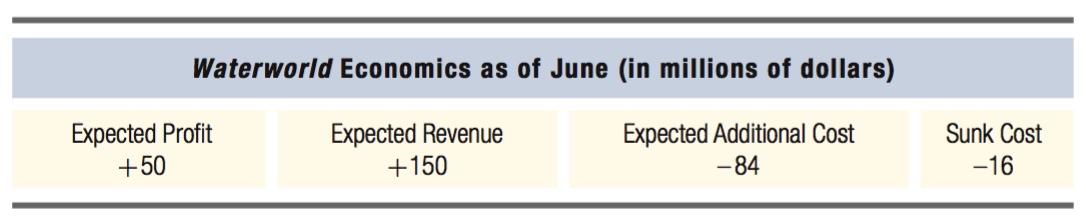

Let’s think through Universal’s decision to complete the movie and release it. At the outset, the studio expected the movie to bring in $150 million of revenue (a 50% cut of an expected $300 million of global ticket sales), and the movie’s budget (for a planned 96 days of filming) was $100 million.2 As filming began, about $16 million of the $100 million expected costs were sunk—

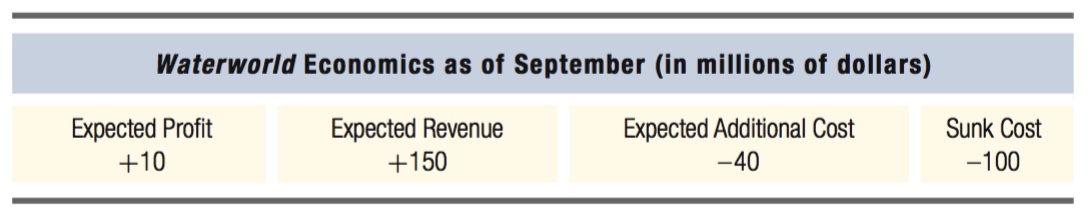

Things started to go wrong quickly. The filming location in Kawaihae Harbor on the Big Island of Hawaii was so windy that scores of the crew became seasick each day. The medicines to alleviate the symptoms made them drowsy and impaired their ability to use cameras and other equipment. Several divers suffered decompression sickness and embolisms from being underwater for too long. There were rumors of contractual meal penalties exceeding $2.5 million because of so many overtime shoots, and a one-

254

Then the biggest accident struck. During a big storm, the “slave colony,” a multi-

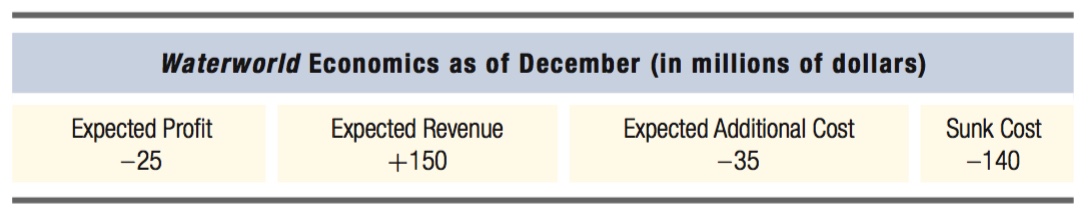

By now, the studio had to know the movie would lose money. If the studio considered sunk costs in making its decision to keep going or close down the production, it would stop production. But, in making this decision, the studio would have been falling for the sunk cost fallacy. To see why, compare the tradeoffs the studio faced when weighing whether to stop filming or to finish the movie. If the studio went ahead and paid the additional $35 million of expected costs to complete the movie, it would earn an expected $150 million of revenue. Of course, it would lose the $140 million of sunk costs, but that would also be true if the studio canceled production instead. Canceling would allow the studio to avoid the incremental $35 million cost, but it would forgo the $150 million in expected revenue. Looking forward and ignoring the sunk costs as it should have, then, the studio faced a choice between an expected incremental gain of $115 million ($150 million in revenue – $35 million in costs) from finishing the movie and an expected incremental loss of $115 million ($35 million in saved costs – $150 million in lost revenue) from halting production.

To be sure, if Kevin Costner and the makers of the movie had had a crystal ball at the start of filming to see what terrible events would transpire and the massive costs that were to come, the decision would have been different. They could have halted production at a loss of only $16 million. But, that would have been before the costs were sunk. Discovering the problems only after having sunk $140 million, on the other hand, meant that it made sense for the movie’s producers to hold their noses and take the belly flop.