8.1 Market Structures and Perfect Competition in the Short Run

market structure

The competitive environment in which firms operate.

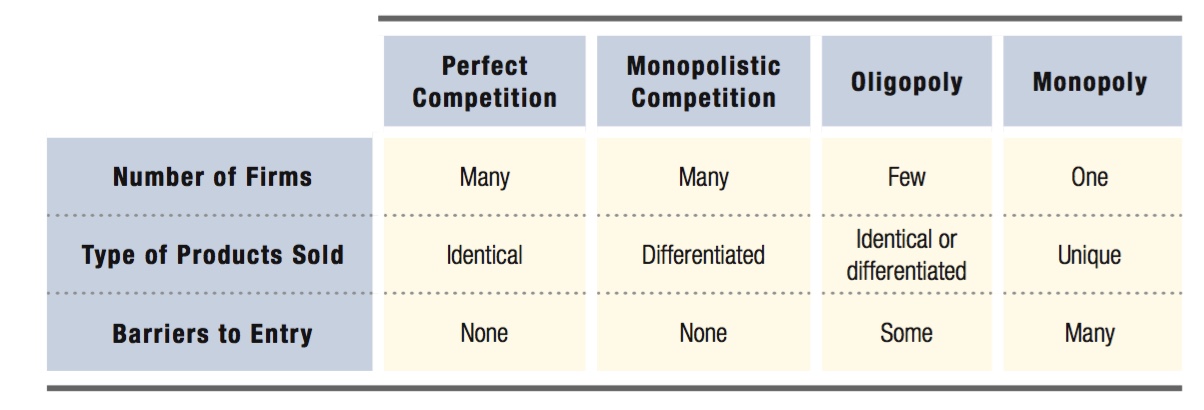

To say more about how a firm makes its production decisions, it is useful to think about the competitive environment, or market structure, in which it operates. There are four different types of markets that we explore in the next several chapters: perfect competition, monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly.

We categorize a market or industry using three primary characteristics:

Number of firms. Generally, the more companies in the market, the more competitive it is.

Whether the consumer cares which company made the good. Can a consumer distinguish one firm’s product from another, or are all of the goods identical? In general, the more indistinguishable the products are, the more competitive the market is.

Barriers to entry. If new firms can enter a market easily, the market is more competitive.

288

Table 8.1 describes each market structure using these characteristics.

These three characteristics tell us a lot about the production decisions of firms in a given industry. For example, firms that can differentiate their products may be able to convince some consumers to pay a higher price for their products than for products made by their competitors. The ability to influence the price of their products has important implications for these firms’ decisions. Only firms in a perfectly competitive market have no influence on the price of their products; they take as given whatever price is determined by the forces of supply and demand at work in the wider market. A truly perfectly competitive market is rare, but it offers many useful lessons about how a market works, just as the supply and demand framework does. In this chapter, we focus on perfectly competitive markets. In Chapter 9 and Chapter 10, we look at monopoly and how monopolies can use different strategies to gain more profit, and in Chapter 11, we examine market structures that fall in between perfect competition and monopoly.

Perfect Competition

There are three conditions that characterize a perfectly competitive market (Table 8.1). First, there need to be a large number of firms so that no one firm has any impact on the market equilibrium price by itself. Thus, any one firm can change its behavior without changing the overall market equilibrium.

The second requirement for perfect competition is that all firms produce an identical product. By identical, we don’t just mean that all the firms make televisions or all the firms make smoothies. We mean the consumers view the output of the different producers as perfect substitutes and do not care who made it. This assumption is more accurate for nails or gasoline or bananas, but less accurate for smartphones or automobiles.

Finally, for an industry to be perfectly competitive, there cannot be any barriers to entry. That is, if someone decides she wants to start selling nails tomorrow, there is nothing that prevents her from doing it.

The key economic implication of these three assumptions (a large number of firms, identical products, free entry) is that firms don’t have a choice about what price to charge. If the firm charges a price above the market price, it will not sell any of its output. (We’ll show you the math behind this result later in this section.) And because we assume that the firm is small enough relative to the industry that it can sell as much output as it wants at the market price, it will never choose to charge a price below the market price. For that reason, economists call perfectly competitive firms price takers. The price at which they can sell their output is determined solely by the forces of supply and demand in the market, and individual firms take that price as given when making decisions about how much to produce.

289

The classic example of a firm operating in a perfectly competitive market is a farmer who produces a commodity crop, such as soybeans. Because an individual farmer’s output is tiny relative to total production for the entire market, the choice of how much to produce (or whether to produce at all) isn’t going to create movements along the industry’s demand curve. One farmer’s decision to sell part or all of her soybean crop will not affect the price of soybeans. The combined effect of many soybean farmers’ decisions will affect the market price, however, just as everyone in a city simultaneously turning on their faucets might cause water pressure throughout the city to drop. The key is that the city’s water pressure won’t fluctuate simply because one person decides to take a shower.

Note one important thing: Having a large number of firms in an industry does not automatically mean the industry is perfectly competitive. In the United States, for example, there are over 2,000 firms that sell ready-

If firms have to meet such strict criteria to be considered perfectly competitive, you might wonder why we bother studying such a special case. There are several reasons why.

First, it is the most straightforward. Because a perfectly competitive firm takes the market price as given, the only decision a firm must worry about to maximize profit is choosing the correct level of output. It doesn’t need to think about what price to charge because the market takes care of that.

Second, there are a few perfectly competitive markets, and it’s useful to know how they work (maybe you’ve dreamed of farming soybeans). Further, there are many markets that are close to perfectly competitive, and the perfect competition model provides a fairly good idea about how these markets work.

Third, and most important, perfect competition is a benchmark against which economists measure the efficiency of other market structures. Perfectly competitive markets are, in a specific sense, the most efficient markets (as we see later in this chapter). In competitive markets, goods sell at their marginal costs, firms produce at the lowest cost possible, and combined producer and consumer surplus is at its largest. Comparing a market to the outcome under perfect competition is a useful way to measure how efficient a market is.

290

The Demand Curve as Seen by a Price Taker

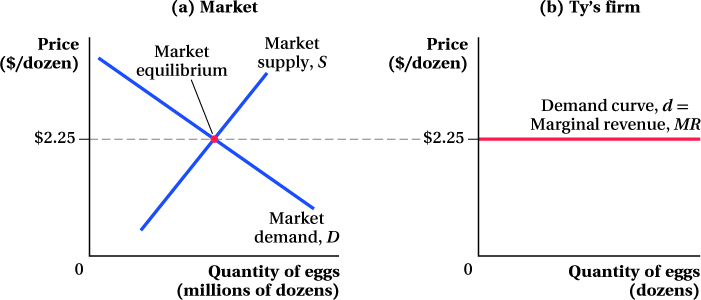

A perfectly competitive firm is a price taker. It must sell its output at whatever price is determined by supply and demand forces in the market as a whole. The small size of each firm relative to the size of the total market means the perfectly competitive firm can sell as much output as it wants to at the market price.

Let’s again think about Ty, our urban egg farmer. The price for a dozen Grade-

(b) Ty, an individual supplier of dozens of eggs in the market, must sell at the price set by the market. Hence, he faces a perfectly elastic demand curve at the market price of $2.25 per dozen.

As a producer in this market, Farmer Ty can sell all the eggs his hens can produce as long as he is willing to sell them at $2.25 per dozen. He can’t sell them for more than that price because, from a consumer’s standpoint, a Grade-

This means the demand curve Ty (or any other egg farmer like him) faces personally is horizontal—