8.3 Perfect Competition in the Short Run

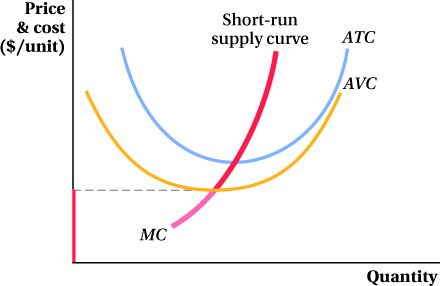

We’ve just learned that a perfectly competitive firm maximizes its profit where MR = P = MC, and that the firm will operate in the short run (even at an economic loss) as long as price is greater than or equal to average variable cost. We can now take our analysis one step further and derive the short-

A Firm’s Short-Run Supply Curve in a Perfectly Competitive Market

Because the supply curve shows the quantity supplied at any given price, and the firm chooses to produce where P = MC, the short-

Figure 8.6 shows that the firm’s short-

Because of this relationship between marginal cost and the firm’s short-

300

Application: The Supply Curve of a Power Plant

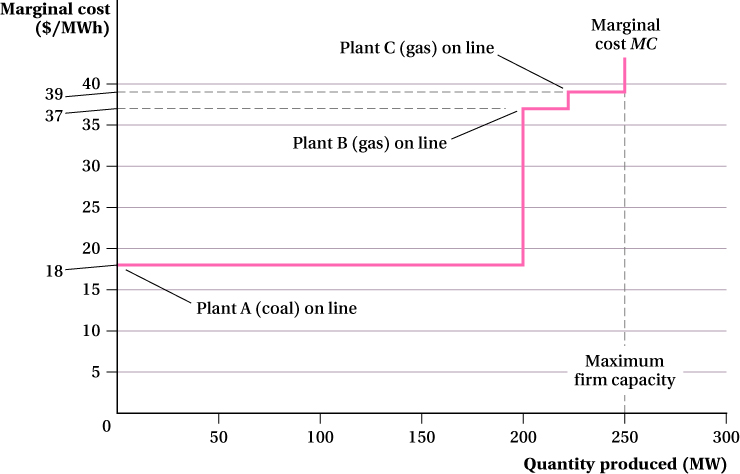

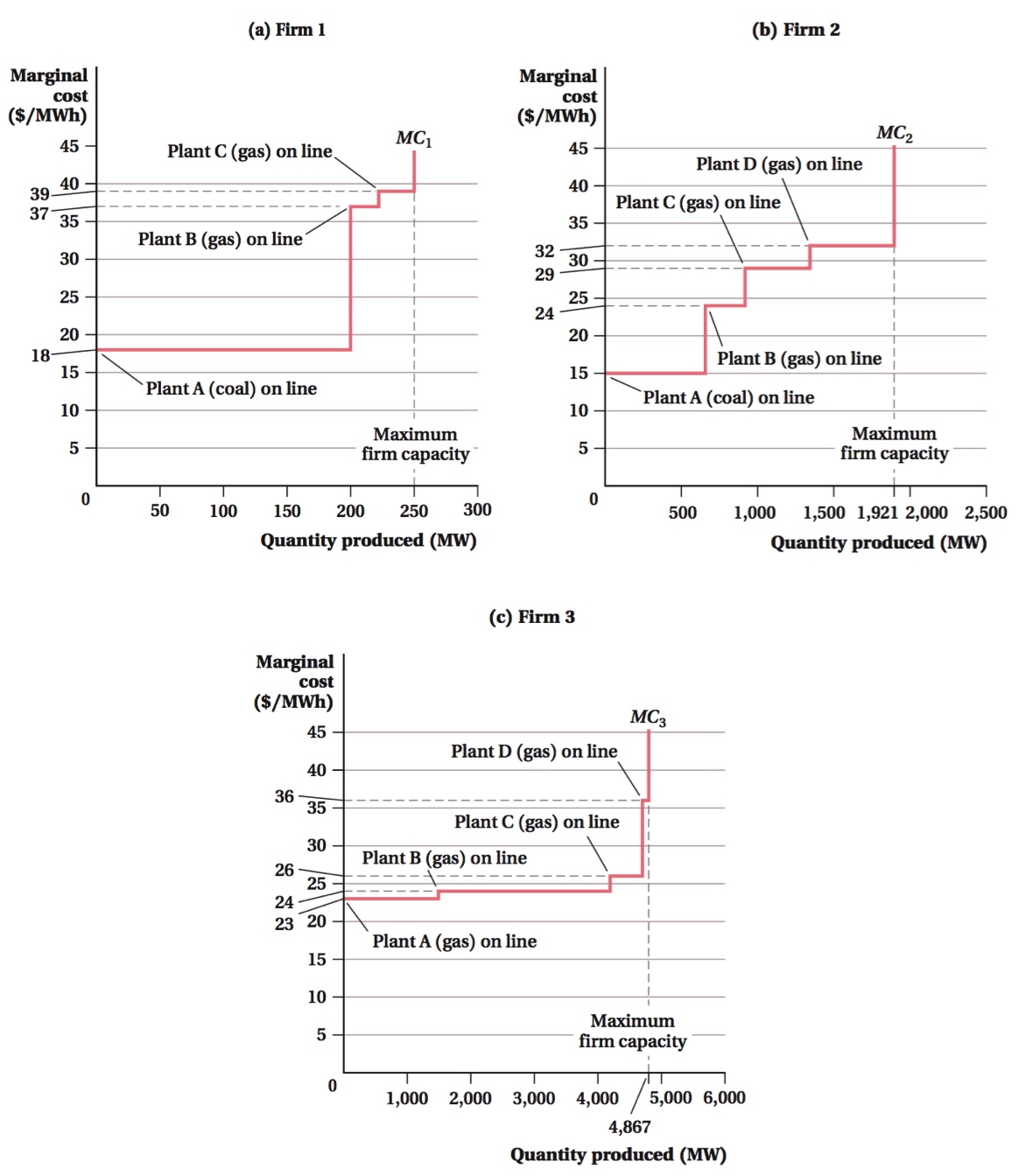

Economists Ali Hortaçsu and Steven Puller published a detailed study of the Texas electricity industry.3 Using data from this study, we can see how to construct the supply curve for a single electricity firm with several electricity plants (Figure 8.7). This, along with the supply curves of the other firms in the industry, is a building block in the industry supply curve that we construct later in the chapter.

The first and most important step in deriving the firm’s supply curve is to determine its marginal cost curve. In the electric power generation industry, marginal cost reflects the firm’s cost of producing one more megawatt of electricity for another hour (this amount of energy, called a megawatt-

Our firm has three power plants. Plant A uses coal to power its generator and has a capacity of 200 megawatts (MW); Plants B and C use natural gas and each has a capacity of 25 MW. Coal generators are generally cheaper to run than natural gas generators.

301

The marginal cost of running Plant A’s coal generator is $18 per MWh and it is constant across the plant’s production quantity up to 200 MW. The plant cannot produce quantities above this level, so the plant’s marginal cost is, in effect, infinite at quantities greater than 200 MW. Plant B’s natural-

If the firm is generating 200 MW or less, only Plant A (its coal plant) will be on line (i.e., producing electricity) because that’s the lowest-

To generate quantities above 200 MWh, the firm has to use at least one of its other generators. If it wants to produce a quantity between 200 and 225 MWh, it only needs to run one of its natural gas plants, and it will put Plant B on line, the one with the smaller marginal cost of the two, $37 per MWh. Therefore, at a quantity of 200 MWh, the firm’s marginal cost curve jumps up to $37 per MWh. It stays at this level up to the quantity of 225 MWh. To produce a quantity above 225 MWh, it needs to put Plant C on line, its natural gas generator with the $39 marginal cost, so the marginal cost curve jumps up to $39 per MWh. The firm’s marginal cost remains at $39 per MWh up to the quantity of 250 MWh. At this point, the firm has exhausted its generating capacity and cannot produce any more electricity. Above 250 MWh, the firm’s marginal costs effectively become infinite. Figure 8.7 reflects this as a vertical line extending off the graph at 250 MWh.

The portion of this marginal cost curve at or above the firm’s average variable cost is its supply curve. We saw in Chapter 7 that a firm’s total variable cost at any quantity is the sum of its marginal cost of producing each unit up to and including that quantity. Therefore, the firm’s total variable cost of producing its first megawatt-

The Short-Run Supply Curve for a Perfectly Competitive Industry

We know that an individual firm in a perfectly competitive market cannot affect the price it receives for its output by changing the level of its output. What does determine the price in a perfectly competitive market? The combined output decisions of all the firms in the market: the industry supply curve. In this section, we look at how this combined output response is determined.

Before we begin, we must clarify what we mean by firms’ “combined” decisions. What we do not mean is “coordinated.” Firms in a perfectly competitive market do not gather at an annual convention to determine their output levels for the year, or have an industry newsletter or website that serves the same function. (Such a practice would typically get a firm’s executives indicted for price fixing, in fact.) “Combined” here instead means aggregated—

302

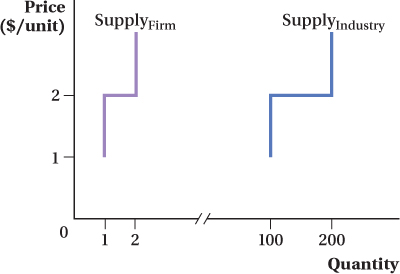

It’s easy to see how you can add up firms’ short-

To derive the industry short-

The Short-

In Figure 8.8, all industry firms have the same short-

303

To illustrate this point, let’s now suppose that the industry (which still has 100 firms) has 50 firms with supply curves like those in Figure 8.8 and another 50 that have different supply curves. Let’s say these other firms have higher costs and therefore will not produce any output at a market price less than $2. For prices greater than or equal to $2 and less than $3, they produce 1 unit of output, and at prices at or above $3, they produce 2 units. Now the industry supply curve is 0 units for prices under $1 because no firms can profitably produce below that price. For prices from $1 to just under $2, industry supply is 50 units; only the 50 low-

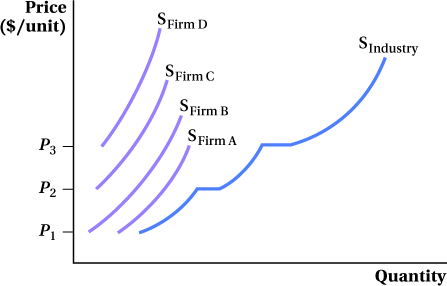

In general, the industry supply curve is the horizontal sum of the supply curves of the individual firms within it. The examples above use very simple “step-

These examples make an interesting point: Industry output increases as price increases for two reasons. One is that individual firms’ supply curves are often upward-

304

Application: The Short-Run Supply of Crude Oil

U.S. politicians are constantly calling for the country to reduce its dependence on oil from the Middle East. About 20% of the oil the United States consumes comes from OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), and about 60% of that (12% of U.S. consumption) is supplied by Middle Eastern countries that are members of OPEC. Many politicians take this to mean that reducing the country’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil is simple: Cut consumption by 12%, and that will effectively eliminate imports from the Middle East. This will also increase the share of imported oil that comes from “friendlier” nations such as Canada.

This type of logic ignores what we know about how perfectly competitive firms make production decisions. We’ve seen that a competitive firm’s short-

While the crude oil market is not perfectly competitive, the same relationship between price and average variable cost holds for all firms. If we reduce our consumption of oil, the countries that will be hurt by a decrease in demand and the price drop that accompanies it will be those with the highest costs—

This outcome has been borne out historically. At least until the drop in oil prices at the end of 2014, the United States actually imported more oil from Canada than it does from the Middle East. In the late 1990s, on the other hand, when crude oil prices were at historic lows, only about 8% of U.S. oil consumption came from Canadian imports, while about 12% of consumption was imported from the Middle East. Thus, if we want to reduce our dependence on the Middle East, cutting back consumption a bit isn’t the answer.

Producer Surplus for a Competitive Firm

The intersection of the short-

At all but the lowest market price levels, firms will sell some units of output at a price above their marginal cost of production. In the Application on Texas electricity generation, for example, Figure 8.7 shows that if the market price is at or above $37 per MWh, the firm would be able to sell the electricity generated by its coal plant at a marginal cost of $18 per MWh at a considerably higher price.

305

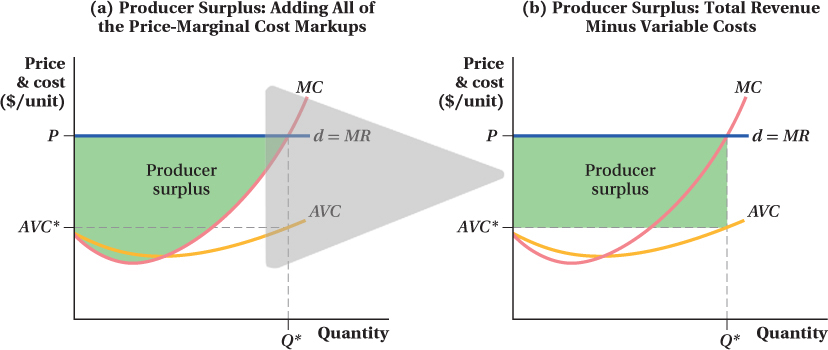

We can see this in a more general case in Figure 8.10 , which shows the production decision of a particular firm. Profit maximization implies the firm will produce Q*, the quantity where the firm’s marginal cost equals the market price P. Notice that for all units the firm produces before Q*, the firm’s marginal cost of producing them is lower than the market price. The firm earns a markup for each of these units.

(b) Producer surplus can also be calculated by a firm’s total revenue minus its variable cost. A firm’s total revenue is the entire rectangle with height P and length Q*, and its variable cost is the rectangle with height AVC* and length Q*. Its producer surplus, therefore, is the area of the rectangle with height (P – AVC*) and length Q*.

If we add up all these price-

There’s another way to compute producer surplus. First, remember from Chapter 7 that marginal cost involves only variable cost, not fixed cost. If we add up the firm’s marginal cost for all the units of output it produces, we have its variable cost. And if we add up the firm’s revenue for every unit of output it produces, we have its total revenue. That means the firm’s total revenue minus its variable cost equals the sum of the price-

PS = TR – VC

In panel b of Figure 8.10 , the firm’s total revenue is the area of the rectangle with a height of P and a base of Q*. Variable cost is output multiplied by average variable cost, so the firm’s variable cost is the area of the rectangle with a base of Q* and a height of AVC* (AVC at the profit-

306

Producer Surplus and Profit

You’re probably not going to be surprised when we tell you that producer surplus is closely related to profit. But it’s important to recognize that producer surplus is not the same thing as profit. The difference is that producer surplus includes no fixed costs, while profit does. In mathematical terms, PS = TR – VC and π = TR – VC – FC.

A new firm may operate with profit less than zero. It will never operate with producer surplus less than zero because that means each unit costs more to produce than it sells for, even without fixed costs. In fact, we can rewrite the firm’s shut-

Producer Surplus for a Competitive Industry

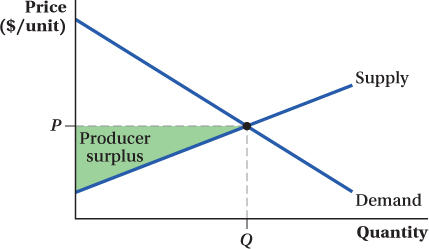

Producer surplus for an entire industry is the same idea as producer surplus for a firm. It is the area below the market price but above the short-

figure it out 8.3

Assume that the pickle industry is perfectly competitive and has 150 producers. One hundred of these producers are “high-

Derive the short-

run industry supply curve for pickles. If the market demand curve for jars of pickles is given by Qd = 6,000 – 300P, what are the market equilibrium price and quantity of pickles?

At the price you found in part (b), how many pickles does each high-

cost firm produce? Each low- cost firm? At the price you found in part (b), determine the industry producer surplus.

Solution:

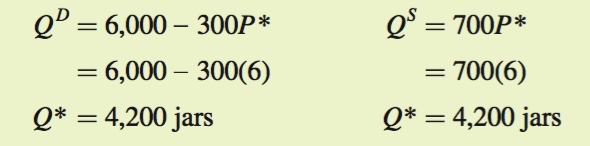

To derive the industry short-

run supply curve, we need to sum each of the firm short- run supply curves horizontally. In other words, we need to add each firm’s quantity supplied at each price. Since there are 100 high- cost firms with identical supply curves, we can sum them simply by multiplying the firm supply curve by 100: QHC = 100Qhc = 100(4P) = 400P

Similarly, we can get the supply of the 50 low-

cost firms by summing their individual supply curves or by multiplying the curve of one firm by 50 (since these 50 firms are assumed to have identical supply curves): QLC = 50Qlc = 50(6P) = 300P

The short-

run industry supply curve is the sum of the supply by high- cost producers and the supply of low- cost producers: QS = QHC + QLC = 400P + 300P = 700P

Market equilibrium occurs where quantity demanded is equal to quantity supplied:

QD = QS

6,000 – 300P = 700P

1,000P = 6,000

P* = $6

The equilibrium quantity can be found by substituting P = $6 into either the market demand or supply equation:

At a price of $6, each high-

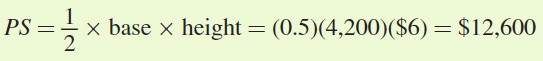

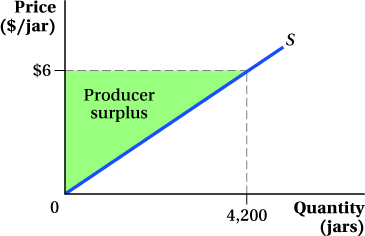

cost producer will produce Qhc = 4P = 4(6) = 24, while each low- cost producer will produce Qlc = 6P = 6(6) = 36 jars. The easiest way to calculate industry producer surplus is to graph the industry supply curve. Producer surplus is the area below the market price but above the short-

run industry supply curve. In the figure below, this is the triangle with a base of 4,200 (the equilibrium quantity at a price of $6) and a height of $6:

307

Application: Short-Run Industry Supply and Producer Surplus in Electricity Generation

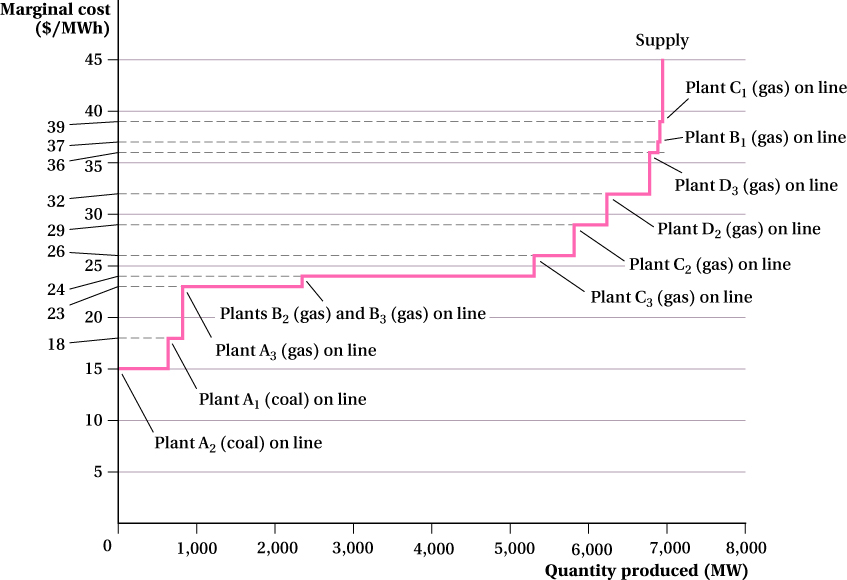

Let’s suppose that Firm 1 from the Application on the Texas electricity industry earlier in this section is in an industry with two other firms. (In reality, the Texas electricity industry comprises many firms, but we have chosen three to make it less complicated.) Like Firm 1, Firm 2 has both coal and natural gas plants, and it relies on its relatively low-

We can construct the industry marginal cost curve by finding the horizontal sum of the three firms’ individual marginal cost curves. This is demonstrated in Figure 8.13. As was true for Firm 1’s marginal cost curve, the industry will rely first on generators with relatively cheaper marginal costs. In other words, the industry will first use all available coal generators. For the first 675 MW, only Firm 2’s coal plant operates, because it has the lowest marginal cost of all the industry’s plants ($15 per MWh). If a higher quantity is produced, Firm 1 brings its 200-

308

309

For all market prices at or above $18 per MWh, the industry is going to have at least one plant operating at a marginal cost that is below the market price. For example, if the market price were $23 per MWh, Firm 1 and 2’s coal plants would both be operating at marginal costs that are smaller than the market price. In other words, price equals marginal cost only for the marginal plant—

310

See the problem worked out using calculus

See the problem worked out using calculus