9.1 Sources of Market Power

Some industries, like computer operating system manufacturers, mobile phone service providers, and car manufacturers, for example, invariably end up with only a few companies having substantial market power. In this chapter, we investigate what differentiates these industries from perfectly competitive ones. We learn how firms in these industries gain the ability to influence the price at which they sell their goods—

barriers to entry

Factors that prevent entry into markets with large producer surpluses.

A key element of sustainable market power is that there must be something about the market that prevents competitors from entering it until the price is as low as it would be if the market were perfectly competitive. A firm with market power can generate a substantial amount of producer surplus and profit in a way that a competitive firm cannot. (Remember that producer surplus equals a firm’s profit plus its fixed cost. In the long run, when fixed cost is zero, profit and producer surplus are equal.) As we saw in Chapter 8, however, producer surplus should be an irresistible draw for other firms to enter the market and try to capture some of it. Barriers to entry are the factors that keep entrants out of a market despite the existence of a large producer surplus that comes from market power. The next few sections discuss the most important barriers to entry.

Extreme Scale Economies: Natural Monopoly

natural monopoly

A market in which it is efficient for a single firm to produce the entire industry output.

The existence of a natural monopoly is one barrier to entry. A natural monopoly refers to a situation in which the cost curve of a firm in an industry exhibits economies of scale at any output level. In other words, the firm’s long-

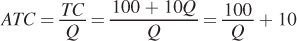

In this type of situation, it is efficient (from a production standpoint) for society if a single firm produces the entire industry output; splitting output across more firms would raise the average total cost of production. Suppose a company could produce as large a quantity as it wants at a constant marginal cost of $10 per unit and has a fixed cost of $100. In this case, average total cost (total costs divided by output) declines across all quantities of output. In equation form,

TC = FC + VC = 100 + 10Q

so

The larger the firm’s quantity produced, Q, the lower is its average total cost. If all the firms in an industry have this same cost structure, the lowest-

333

Many economists believe electricity transmission is a natural monopoly. The fixed cost of building a network of transmission lines, substations, meters, and so on, to supply homes and businesses is very large. Once the network is built, however, the marginal cost of delivering another kilowatt-

Because electricity transmission companies are often natural monopolies, they are regulated by the government. Later in the chapter, we discuss why the government often regulates the behaviors of firms with market power whether their market power is the result of a natural monopoly or not. All that said, it is important to realize that even natural monopolies can disappear if demand changes sufficiently over time. Demand can rise so much that average total cost eventually rises enough to enable new firms to enter the market. It has been argued that this happened in a number of markets formerly believed to be natural monopolies, such as the markets for telephone and cable television service.

Application: Natural Monopoly in Satellite Radio

A real-

The two services were similar technologically, so they tried to distinguish themselves from each other in customers’ minds based on content. XM signed an exclusive deal to carry all NFL football games on the radio, for example. Sirius signed deals to carry all MLB baseball games and to carry shock-

It didn’t work. Because the cost structure of a satellite radio company comprises a whopping fixed cost (operating dozens of radio channels and building and launching satellites) and a very low marginal cost, splitting the market meant that both companies operated at high levels of average total cost. They each incurred large losses as a result. The economics of the market said that two firms shouldn’t exist, and the market finally realized this: Eventually, XM and Sirius merged to become one firm.

Switching Costs

A second common type of barrier to entry is the presence of consumer switching costs. If customers must give something up to switch to a competing product, this will tend to generate market power for the incumbent and make entry difficult. Think of a consumer who flies one airline regularly and has built up a preferred status level in the airline’s frequent-

334

For some products, the switching cost comes from technology. For example, once you buy a DirecTV satellite dish and install it on your house, the only way to switch to the DISH Network is to get a new satellite dish and converter box installed. Similarly, once you have typed in all your shipping information at Amazon or built up your reputation at eBay, you can’t just transfer that information to a competitor. These conveniences for you are a barrier to entry in the market for online retailers or auction sites.

For other products, switching costs arise from the costs of finding an alternative. If you have your car insurance with one company, it can be very time-

Switching costs are not insurmountable barriers to entry. For example, some companies invest in trying to make comparing new options as easy as possible to convince people to swallow the switching costs and go with their (often) cheaper product. Progressive Insurance, for example, includes a feature on its Web site that lets customers compare what their auto insurance premiums would be not just with Progressive, but with several of their competitors as well. But switching costs don’t need to be insurmountable to be effective. To reduce the threat of competition and give the incumbent firm some market power, switching costs only need to be high enough to make entry costly, not impossible.

network good

A good whose value to each consumer increases with the number of other consumers of the product.

Perhaps the most extreme version of switching costs exists with a network good: a good whose value to each customer rises with the number of other consumers who use the product. With network goods, each new consumer creates a benefit for every other consumer of the good. Facebook is one example of a network good. If you are the only person in the world on Facebook, your account is not going to be much fun or very useful. If you’re one of millions with accounts, however, now you’re talking (. . .to each other).

The combination of large economies of scale (at or approaching natural monopoly levels) and network goods’ attributes creates powerful entry barriers. Computer operating systems like Microsoft Windows are prone to become monopolies because they both have major economies of scale in production (software is a high-

Product Differentiation

product differentiation

Imperfect substitutability across varieties of a product.

Even if firms sell products that compete in the same market, all consumers might not see each firm’s product as a perfect substitute for other firms’ versions. For example, all bicycle makers operate in what could be thought of as the same market, but not every potential bike buyer will see a $500 Trek as exactly the same thing as a $500 Cannondale. That means firms can price slightly above their competition without losing all of their sales to their competitors. There is a segment of consumers who have a particular preference for one firm’s product and will be willing to pay a premium for it (a limited premium, but a premium nonetheless). This imperfect substitutability across varieties of a product is called product differentiation, and it is another source of market power.

In some industries, product differentiation can be spatial. When location matters, some sellers are in more convenient, appealing, or noticeable locations for some customers than others. Those sellers will have some market power because even if their price is a bit higher than another more distant competitor, not all of their customers will be willing to switch to the other seller. Likewise, their competitor has some customers who prefer its location, giving it some market power as well.

335

Product differentiation exists in one form or the other in most industries. Regardless of its specific source, it prevents new firms from coming into the market and stealing most of the market demand just by pricing their product version a bit below the incumbents’ prices. We discuss product differentiation in greater detail in Chapter 11.

Absolute Cost Advantages or Control of Key Inputs

Another common barrier to entry is a firm’s absolute cost advantage over other firms in obtaining a key input. If a firm has control of a key input, that means it has some special asset that other firms do not have. For example, a key input might be a secret formula or a scarce resource. Controlling this input allows a firm to have costs lower than those of any competitor. To give an extreme example, suppose one firm owns the only oil well in existence and can prevent anyone else from drilling one. That would be a major advantage, because everyone else’s cost of producing oil is infinite. The control of the input does not need to be that extreme, though. If a firm has one oil well whose production cost is substantially below that of everyone else’s wells, that would be a cost advantage, too. These other firms would find it difficult to take business away from the low-

Application: Controlling a Key Input—The Troubled History of Fordlandia, Brazil

In the 1800s, there was no synthetic rubber. All rubber came from trees, and Brazil’s rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) were the world’s leading source. Rubber was one of Brazil’s great exports.

In their natural state, the trees were often miles apart and hard to reach. In addition, because South American leaf-

In 1927 Henry Ford needed rubber for car tires and tried to copy the British. He set up a rubber plantation city in the Amazon and called it Fordlandia. Unfortunately, because Ford never consulted any experts on rubber trees, the Fordlandia plantation rapidly fell prey to the leaf-

Britain’s market power from the absolute cost advantage of controlling this key input (rubber plants not threatened by the fungus) survived until the development of cheap synthetic rubber after World War II. It’s still true, though, that if you travel from Brazil to Malaysia, the Malaysian government requires you to walk through a fungicide treatment at the airport and irradiates your luggage with ultraviolet radiation to kill any South American leaf blight you might be harboring.

336

Government Regulation

A final important form of entry barrier is government regulation. If you want to drive a cab in New York, you need to have a medallion (a chunk of metal that is actually riveted to a car’s hood to show that the New York Taxi & Limousine Commission has granted the cab a license to operate). The number of medallions is fixed; currently, there are just over 13,000 available. If you want to enter this industry, you need to buy a medallion from its current owner, and the price runs in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. That’s a considerable entry barrier for a taxi driver.

Uber, a ride-

There are numerous other rules that prevent entry, such as licensing requirements in many occupations and industries. Note, however, that some regulatory barriers are intentional and probably good, as we discuss later in the chapter when we consider government responses to monopoly. Examples include things like patents and copyrights, which explicitly give companies protection from entry by forbidding direct competitors.

Where There’s a Will (and Producer Surplus), There’s a Way

One important aspect to remember about barriers to entry is that they seldom last forever. If the producer surplus protected by entry barriers is large, competitors can often eventually find their way around even the most formidable barriers to entry. DuPont invented Nylon, the synthetic material, and patented it. In theory, this should have prevented entry. In reality, other companies figured out ways to develop competing, though not identical, synthetic fabrics that ultimately undermined the Nylon monopoly. Because there is no limit to the inventive capacity of the human mind, in the long run entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial firms will often find ingenious ways to encroach on other firms’ protected positions.