9.6 Governments and Market Power: Regulation, Antitrust, and Innovation

We’ve seen the impact that market power can have on an industry—

361

Direct Price Regulation

When there is a concern that firms in an industry have too much market power, governments sometimes directly regulate prices. Often, this occurs in markets considered to be natural monopolies. If it appears that there is no way to prevent the existence of a natural monopoly because of the nature of the industry’s cost structure, the government will often allow only a single firm to operate but will limit its pricing behavior to prevent it from fully exploiting its market power. Governments have used this argument to justify regulating, at various times, the prices of electricity, natural gas, gasoline, cable television, local telephone service, long-

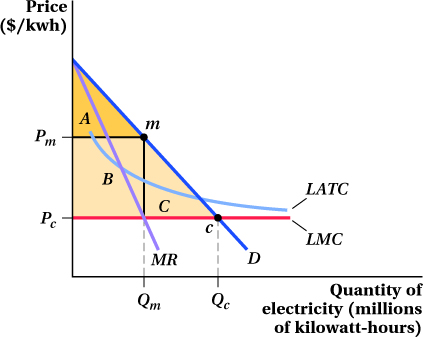

To understand the logic behind these actions, consider a typical natural monopoly case as shown in Figure 9.8. Let’s suppose it is the market for electricity distribution, which we argued earlier may, in fact, be a natural monopoly. With a demand curve of D, an unregulated electric company would produce at the point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. This would lead to a price of Pm, substantially higher than the firm’s marginal cost. The consumer surplus in this situation will be only the area A, rather than the area A + B + C, as would be the case if prices were instead set at Pc, a level equal to the firm’s marginal cost.

If the government imposes a price cap regulation that forbids the electric company from charging prices above Pc, output could equal its perfectly competitive level, and consumer surplus will equal area A + B + C. But there’s a problem. Pc is below the firm’s average total cost; if it sells every unit it produces at the regulated price, the firm will earn a negative profit, as it won’t be able to cover its fixed cost. Therefore, a simple price regulation requiring competitive pricing is not a sustainable solution in regulating a natural monopoly. However, any regulation that would allow a price above marginal cost in order to permit the natural monopolist to recoup its fixed cost would also lead to a deadweight loss and less consumer surplus than the competitive case (though the deadweight loss may be smaller and the reduction in consumer surplus smaller than in the unregulated monopoly case).8

362

Aside from this problem, there are several other serious difficulties involved in using direct price regulations. First and foremost, only the company knows its true cost structure. Government regulators don’t actually know the firm’s marginal cost or, for that matter, what the full demand curve is. It’s difficult to set the regulated price at the perfectly competitive level without knowing these two pieces of information. So, the regulator is left to estimate them. Further, the firm has an incentive to misrepresent the truth and make people believe its costs are higher than they really are, because this would justify a higher regulated price. In addition, companies that are regulated based on their cost often have no incentive to reduce their costs because the regulator would then reduce the regulated price, destroying any profit gained from the increase in efficiency.

Antitrust

antitrust law

Laws designed to promote competitive markets by restricting firms from behaviors that limit competition.

Another approach governments use to address the effects of market power is antitrust law (sometimes called competition policy outside the United States). Antitrust laws are meant to promote competition in a market by restricting firms from certain behaviors that may limit competition, especially if the firm is an established and substantial current player in the industry. In some cases, antitrust laws are used to prevent firms from merging with or acquiring other firms in order to stop them from becoming too dominant. Occasionally, these laws are even used to force the break-

One of the strongest and most common prohibitions in antitrust law is the ban on collusion among competitors with regard to pricing and market allocation (agreements to divide up a market among firms). In the United States, for example, even discussing prices or market entry strategies with your competitors is a criminal act.

The antitrust authorities are also allowed to investigate whether a firm is monopolizing an industry unfairly and, if so, they can sue to change the behavior. There have been many such investigations in recent years—

The drawbacks of antitrust enforcement as a way of preventing market power have to do with the large potential costs and uncertainties involved. The government should not fight mergers and acquisitions that would increase efficiency and make consumers better off, but only those that would harm them. The problem is that it’s often hard to tell those two cases apart ahead of time.

363

Promoting Monopoly: Patents, Licenses, and Copyrights

Even as the government tries to limit market power through regulation and antitrust policy, it sometimes encourages monopolies and helps them legally enforce their market power by conferring patents, licenses, copyrights, trademarks, and other assorted legal rights to exercise market power.

Why would the government do this if it cares about consumers and competitive markets? Why give inventors a 20-

Collectively, all of the monopolies created by the government add up to immense amounts of market power that inevitably lead to higher prices and lower quantities than would exist in a competitive market. The reason why it still might make sense for the government to do this is for the sake of encouraging innovation. Giving someone the exclusive right, at least temporarily, to the profits from innovation can provide a powerful incentive to create new things. Governments have decided that the consumer surplus created by these new goods can outweigh the deadweight loss from their producers having market power for a period of time. In some cases, innovation can be the upside of market power.

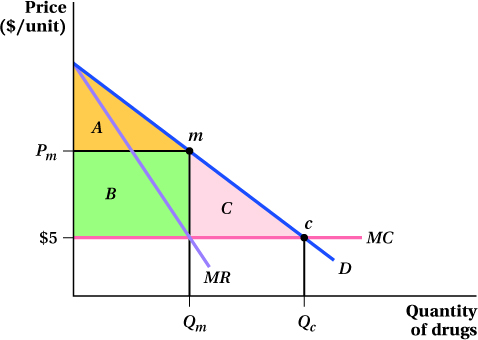

To see why, think about the market for a medical drug to cure the common cold, which affects hundreds of millions of people every year. There would certainly be demand for the product. We label that demand curve D in Figure 9.9.

Let’s assume that the marginal cost of producing a dose of this medicine once it is discovered is constant at $5. (Once a drug is in production, the marginal cost of manufacturing it is very low. It doesn’t cost much to make another pill or another dose of vaccine using a formula that’s been developed and a production line that’s already built.) The rest of the world would like the drug company that discovers the cure to act like a perfectly competitive firm and sell it at the marginal cost of $5 per dose, as at point c. This would create the largest possible consumer surplus of A + B + C.

364

The problem is that selling the drug for $5 would leave the drug company with no producer surplus. Because the firm would need to expend massive amounts of fixed cost on discovering and developing the drug, it will not bother to do so if it immediately has to sell the drug at marginal cost. In other words, having to act like a perfectly competitive firm as soon as it develops this new drug would mean the firm won’t want to actually develop the drug in the first place.

In theory, the government could try to subsidize the development cost (and it does subsidize many types of research and development), but all sorts of problems arise, such as trying to figure out what will work, avoiding corruption, and so on.9 Instead, the government makes a compromise. It promises the firm a monopoly on any drug it develops. The company realizes this means it can produce the quantity level Qm (where MR = MC) and charge a price of Pm, giving it a producer surplus equal to area B from selling a new drug. Therefore, as long as the firm expects the fixed cost of discovering the drug to be smaller than the producer surplus B, it will set out to discover the cure for the common cold. Ultimately, this benefits consumers by giving them a consumer surplus equal to area A. This is lower than the consumer surplus consumers would get in a competitive market (A + B + C), but given that the firm would not have developed the drug in the first place if it had to charge a competitive price, consumers are better off with the more limited consumer surplus of A than none at all.

Overall, the economics of intellectual property protection suggest that it will tend to lead to innovations in just the types of goods that people like most. If a market for an innovation is large because there are a lot of consumers who would want to purchase it, that will tend to also make the monopoly profits in that market big. In addition, recall that in Chapter 3, we saw that goods with steeper demand curves tend to be those with the highest consumer surplus. Earlier in this chapter, we observed that the steeper demand curves are exactly those where monopoly profits are largest. So, a patent, license, or copyright that gives innovators a monopoly will tend to encourage innovation in exactly the types of goods that people value. The downside, of course, is that this will tend to lead to high prices as well.

Application: Patent Length and Drug Development

In the United States as with most countries’ patent systems, the monopoly right granted by the patent lasts for a period (20 years in the United States). This period begins when the patent application is filed, not when the application is approved or when the product is first sold. This timing detail is important in explaining what kinds of drugs are developed, and often it distorts development away from drugs that could have greater benefits than the ones that are actually brought to market.

Economists Eric Budish, Benjamin Roin, and Heidi Williams looked at how this issue affected the development of cancer drugs.10 Different drugs are designed to fight cancer at different stages of the disease. Some are more effective for early-

365

The reason for this is built into the designs of the patenting and drug development process. Pharmaceutical developers typically apply for a patent on a new drug just before it begins clinical trials, because that is when the drug’s chemical compound must be released as public information. This compound could be easily copied by other companies if the developers didn’t apply for a patent. At the same time, the pharmaceutical manufacturers cannot start selling the drug just because they’ve applied for a patent. To do that, the drug has to first earn the approval of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is granted only after the drug has been shown to be safe and effective in clinical trials. This process means that there is a gap between when a drug’s patent application is made (and when its 20-

The length of that gap and how it varies across types of drugs are the key parts of the cancer drug story. The cancer drugs with the shortest clinical trials tend to be those designed to treat late-

The situation is different for early-

Pharmaceutical companies recognize this issue. The length of time during which they can sell their drugs under patent protection will be longer for late-