Consider Your Interests, Values, and Skills

Your academic and career choices will be as individual as you are, so the best way to start planning for these two important aspects of your life is to know yourself. And that means thinking critically as you gather and interpret information about your own interests, values, and skills — and then use the resulting insights about yourself to start building future plans.

WRITING PROMPT: Ask students to write about what their academic and career path has been up to this point. Have they been on a straightforward path or on one with many twists and turns? Are they just getting started along a path now? What do they want their path to look like going forward?

Explore Your Interests

As we discuss in the chapter on building a foundation for success, your interests are your personal preferences — for example, what you like to do in your free time, what course subjects you enjoy, how you like to work, and with whom. These preferences can shed light on what kinds of courses and careers you might find most satisfying. If you don’t have a clear idea of your interests or you want to learn even more about yourself, the strategies in this section can help.

Take an Interest Inventory. One way to investigate your interests is to take an interest inventory, which is a survey of your preferences. A useful and free inventory is the O*NET Interest Profiler, which you can access at www.mynextmove.org/explore/ip or by searching online using the phrase “my next move interest profiler.” Completing this inventory may take 10–15 minutes but it’s worth it — your results will help you think about jobs or professions that may appeal to you. Plus, the inventory can help you with academic planning by giving you insight into what kinds of courses and majors you’d find most intriguing. Complete this inventory now, and then we’ll discuss how to interpret your results.

FOR DISCUSSION: Discuss with students what it was like to take the interest inventory. Were they surprised by their results? How can these scores help them make decisions academically and vocationally?

FOR DISCUSSION: Point out to students that the inventory may also shed light on hobbies that they might enjoy. Having a hobby is a great way to guard against the stress of everyday life.

Understand Holland’s Interest Types. Once you have the results of your interest inventory, the next step is to look at what they mean. The inventory is based on the work of John Holland, a renowned career psychologist who developed a system that describes people and work environments using six categories: Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional.1

CONNECT

TO MY EXPERIENCE

Think about a job, an extracurricular activity, or a volunteer experience you had in the past. What Holland interest area best describes that experience? Write down which aspects of that experience you enjoyed the most and the least, and explain why. Use these insights to brainstorm the kinds of jobs you want to pursue (or avoid) in the future.

Realistic (R). People with Realistic interests enjoy working with their hands, working outside, using tools, installing and repairing things, or working with animals, and they enjoy studies that give them these opportunities. They’re drawn to occupations in such fields as construction, veterinary and earth sciences, landscaping, and other work that’s done primarily outdoors or in physically demanding environments — for example, forestry, physical education, athletics, personal training, and recreation or wildlife management.

Investigative (I). People with Investigative interests like analyzing and solving problems and enjoy science, technical, or medicine-oriented courses. They find satisfaction in almost all areas of science and may work as university professors, doctors, and engineers or do research and development work in most industries.

Artistic (A). People with Artistic interests are creative, intuitive, sensitive, and expressive. They prefer working with ideas and expressing their ideas through writing, sculpting, dancing, painting, acting, or musical performance. Some gravitate toward art-related studies and work as art instructors, as dance therapists, or in the fashion industry. Others write for newspapers or magazines or work as freelance writers.

Social (S). People with strong Social interests enjoy helping, coaching, teaching, or counseling others. They may be drawn to studies and careers related to teaching, child and elder care, or community leadership and social justice. They may become psychologists, physical therapists, social workers, or occupational therapists.

Enterprising (E). People with strong Enterprising interests like to influence, lead, persuade, and manage others. They may enjoy business studies and gravitate toward careers that emphasize fundraising, human resources, law, or management.

Conventional (C). People with Conventional interests usually prefer structure in their school and work environments. They tend to be detail oriented, enjoy working with numbers or data, and are precise in their work. They frequently find satisfaction in the banking and finance industries, the computer sciences, or organizational departments such as payroll and purchasing.

ACTIVITY: Ask students to group themselves according to their dominant Holland interest type. Then have each group brainstorm careers related to this type. Ask students to report their findings back to the class.

As you consider the results of your inventory, keep in mind that it’s perfectly normal to have interests in more than one of these areas. If your interests span two or three categories, the key is to consider which studies and occupations would let you combine your varied interest types. For example, in school, choosing more than one major might let you explore several academic interests, such as business and recreation. In the work world, being an art gallery director might let you express both your Artistic and Enterprising interests, and working as an outdoor adventure counselor might satisfy your Social and Realistic interests. Later in this chapter, we’ll look more closely at how to use knowledge of your interests to explore possible careers.

Explore Your Values

Your values are what you consider important — really important (see the chapter on building a foundation for success). They stem from your experiences with your family, your community, or your faith. Because you’re in college, your academic values probably include getting a good education; if you’re the first in your family to go to college, they may also include making your family proud.

In addition to academic values, you also have work values. These are the aspects of your work or your work environment that you consider important. To learn more about your work values, examine the items on the list below and ask yourself: How important are each of these values to me?2

Work Values: The aspects of your work or your work environment that you consider important.

Achievement: using your abilities and gaining a feeling of accomplishment

Independence: trying out your own ideas, making your own decisions, and working without supervision

Recognition: having opportunities to advance in your career, direct the work of others, and be recognized for your accomplishments

Relationships: getting along with coworkers, doing things for other people, and not having to do things that violate your ideals

Support: receiving helpful supervision, being treated fairly by your organization, and getting appropriate training

Working conditions: being busy all the time, receiving appropriate pay, feeling secure in your job, and constantly doing different activities

ACTIVITY: Ask students to write down the list of work values presented in this section. Next, have students rank order the values using numbers 1 to 6, with 1 being the most important to them and 6 being the least important, based on how they view work today. Then, if possible, have students rank order the work values based on how they viewed work a year ago. Did the order change? Why or why not?

Understanding your work values — and their relative strength — can help you identify careers, and academic programs related to those careers, you might find satisfying. It can also help you make trade-offs. For example, if you become an elementary school teacher, you may have relatively little opportunity for advancement, and you probably won’t get rich. But you’ll go to work each day knowing you’re helping others learn. Depending on your work values, this trade-off might be worthwhile — or it might not. Also note that some careers reinforce certain values and not others, depending on the setting or specialty. In the law profession, for instance, corporate lawyers typically earn a lot more money than public defenders do. If the law appeals to many of your work values but one of your strongest values is financial security, you might aim for a career in corporate law.

WRITING PROMPT: Ask students to think about their ideal job and then list at least ten values they think are associated with this job. Are these values similar to their own work values? Have them compare and contrast the results.

As you consider your work values, keep two things in mind: First, if you don’t have much work experience, you may not have a clear picture of your work values just yet. That’s okay: Your values will come into sharper focus as you get experience. Second, work values can change. For instance, someone who’s raising a family may consider job security a critical work value. Once his children are grown, however, job security may not be as important, and perhaps he’ll place more value on work that lets him feel that he’s contributing to society. The upshot? Understanding your work values is an ongoing process, not a one-time event.

Explore Your Skills

As a college student, you probably excel at, and enjoy using, certain academic skills more than other skills. For instance, maybe you take detailed, accurate notes and ace most tests, but you find it more challenging (and terrifying) to make class presentations. The same is true about the work world. Take Janelle, a computer programmer. Her work involves writing computer code, reading project specifications, using logic and reasoning to solve problems, understanding her clients’ and supervisors’ needs, and managing her time so her projects stay on schedule. She loves writing code, but she dreads meeting with clients. By understanding her skills, she can look for a programming job that emphasizes what she’s good at and what she enjoys — a position that focuses more on writing code than on tending to client relationships.

When it comes to work skills, here’s another important point: Some are specific and are needed in only a few careers — such as writing computer code. Others are transferable and are used in many different careers — such as solving problems with logic and reasoning, listening to others, and managing your time. Your transferable skills let you cast your “career net” more widely, opening up a wider range of occupations that you could succeed in.

WRITING PROMPT: Ask students to make a list of transferable skills they possess and to think about specific examples they can use to demonstrate each skill listed. How can these skills transfer to jobs that interest them?

But you don’t have to limit your options to work experiences that call for only your best skills. You can also seek out experiences that will let you develop new skills or strengthen your current skills. For instance, suppose you’d like to enhance your leadership skills. You could identify volunteer opportunities, leadership positions in campus clubs and organizations, part-time work, and training opportunities at your employer (if you’re currently working) that would help you become a more confident leader. You might even establish a goal to develop this skill over the next few months, which you can document in your Personal Success Plan.

ACTIVITY: Ask students to think about their ideal job, or a job that interests them. Does this job require skills that they currently lack? If so, encourage students to create SMART goals to develop these skills.

HOPE AND ENGAGEMENT PROMOTE ACADEMIC SUCCESS AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

spotlight onresearch

According to a study presented in the chapter on building a foundation for success, students who have high levels of hope stay in school and graduate at a higher rate than those with less hope. But hope is also related to other important components of academic and career success, as revealed by a recent research collaboration between Penn State and the University of British Columbia.

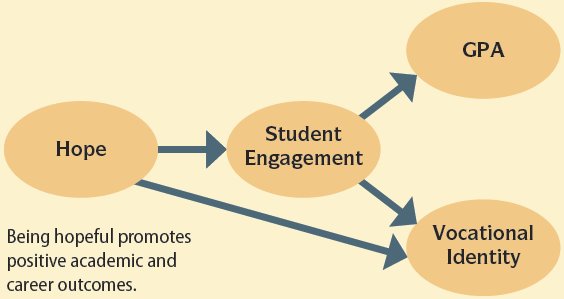

Researchers measured a number of items: levels of hope, student engagement on campus (such as active and collaborative learning and student-faculty interactions), grade point average (GPA), and vocational identity, which is a person’s understanding of his or her career goals, interests, and strengths. They discovered the following relationships.

Students with higher levels of hope were more engaged, and students with high engagement scores achieved higher GPAs.

Students who had high levels of hope and who were engaged on campus also had much stronger vocational identities.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Maintaining a positive attitude, including remaining hopeful, may help you engage more actively in your learning, earn higher grades, and gain the personal insights needed to make good career-related decisions.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Question 13.1

1. How hopeful are you about your career future?

Question 13.2

2. On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the strongest, how would you rate your vocational identity? That is, how well do you understand your own career goals, interests, and strengths?

Question 13.3

3. What steps could you take today to strengthen your vocational identity?

N. Amundson, S. Niles, H. J. Yoon, B. Smith, H. In, and L. Mills, “Hope-Centered Career Development for University/College Students: Final Project Report,” last modified 2013, http://www.ceric.ca/ceric/files/pdf/CERIC_Hope-Centered-Career-Research-Final-Report.pdf.