Use Bloom’s Taxonomy

Now that you’ve read about the basics of critical thinking, let’s explore how you can apply these skills to learning — which is, after all, your core reason for being in college. Just as there are different levels of thinking, there are different levels of learning — and some of them require more critical thinking skills than others.

To get a sense of how the different learning levels work together, think about your experiences in school over the years. When you were in elementary school, you focused mostly on the fundamentals, such as learning how to spell, do simple arithmetic, and remember facts (like names and dates for historical events). But you may not have thought deeply about what you were learning. For example, you probably knew that Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue from Europe to the Americas in 1492, but you may not have pondered why he made the trip or what impact his arrival had on the peoples already living in the Americas.

As you’ve progressed in your education, though, you’ve used critical thinking skills more and more. You’ve likely learned that some questions have more than one right answer and that there can be multiple opinions on a topic. For instance, you and others may have come up with different answers to the question of whether Columbus’s arrival in the Americas benefited the people already living there. To deal with such ambiguities, you used critical thinking skills (maybe without even knowing it) to compare, contrast, and evaluate information. Now that you’re in college, these sophisticated, higher-level thinking skills are more important than ever.4

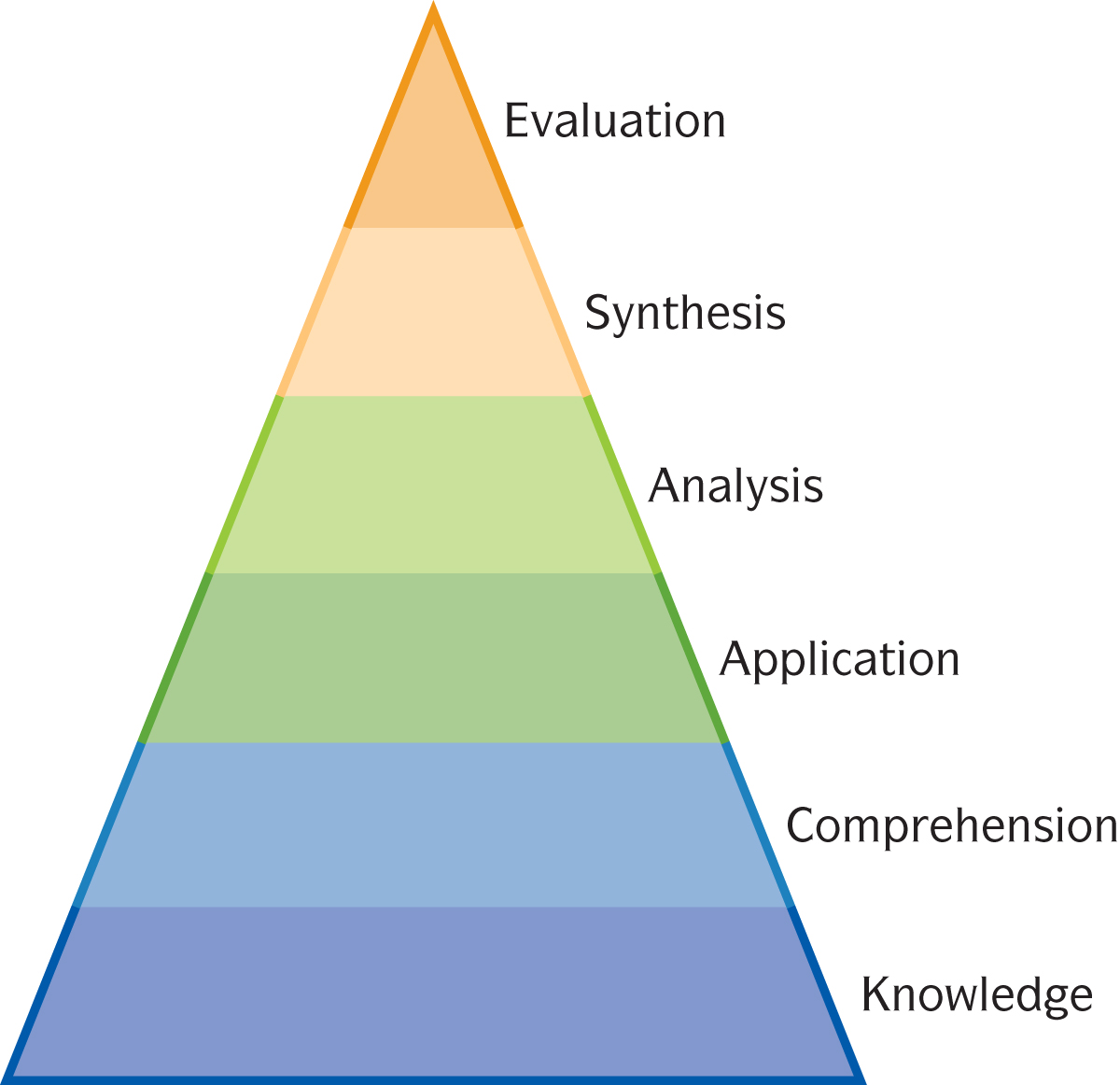

To better understand how learning moves from a simple to a more complex form, consider the work of educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom.5 Bloom’s taxonomy (Figure 2.1) shows how critical thinking relates to different levels of learning. The lowest level represents learning in its simplest form. At the higher levels, learning becomes more complex — and that’s when you really start needing critical thinking skills. Not everything you learn in college will involve these higher levels of learning, but much of it will. Let’s explore each level in more detail.

Knowledge. Knowledge is the most basic level of learning. When you learn a set of facts and recall them on a test, you demonstrate knowledge. Perhaps you know that the American Revolution ended in 1783 or that the Cuban missile crisis happened in 1962. Think of these facts as forming a foundation you can build on to better understand a topic.

Comprehension. At this level, you can restate facts in your own words, compare them to each other, organize them into meaningful groups, and state main ideas. For example, in your communications class, you may learn two facts: Facebook was launched in 2004, and the current CEO is Mark Zuckerberg. You might categorize Facebook as a type of social media platform, a group that also includes Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram, and Flickr. You might further organize these platforms into groups that focus on sharing pictures and those that don’t.

Application. At this level, you use knowledge and your comprehension of it to solve new problems. For example, if you need to hire a new employee, you might read articles about how to attract top candidates and then use the information to conduct your search and to evaluate applicants for the job. In this way, you apply what you read to a real-life challenge.

In some college majors, including business, economics, the sciences, health care, and engineering, you’re expected not only to understand a topic but also to apply your understanding to real problems. In a science class, for example, you may learn how various metals react when subjected to high heat. Later, when asked to identify a mystery metal in science lab, you might heat the metal to test whether it behaves more like magnesium, aluminum, or nickel.

Analysis. At this level of learning, you approach a topic by breaking it down into meaningful parts and learning how those parts relate to one another. You may identify stated and unstated assumptions, examine the reliability of information, and distinguish between facts and educated guesses or opinions.

You’ll be expected to use this level of learning frequently in college. For essay exams, group projects, debates, and term papers, you’ll formulate arguments based on data. In a modern history course, for example, you may analyze how conflict in the Middle East influenced the foreign and domestic policies of President George W. Bush.

Page 29Synthesis. When you synthesize, you make connections between seemingly unrelated or previously unknown facts to understand a topic. As you weave new information into your existing understanding of a topic, you’ll understand that topic in new and more sophisticated ways. You can think of synthesis as advanced analysis.

Here’s an example of synthesis: To develop a research question for a psychology class, you review research findings on altruism (doing good things for others). You learn that people are less likely to help others when they don’t feel a personal sense of responsibility or when there are many other people around who could also help. You use this information to propose a new study on the likelihood that students in the college cafeteria would help a person who slipped and spilled her tray.

Evaluation. At this highest level of learning, you develop arguments and opinions based on a thorough understanding of a topic and a careful review of the available evidence. For instance, an essay question might ask you to establish a position for or against the current U.S. strategy to combat global terrorism. Evaluation is the “expert” level of learning — a level you’ll want to achieve in college, especially in your chosen major. After all, would you want to cross a bridge built by an engineer who hadn’t reached the expert level of engineering? We wouldn’t either.

FURTHER READING: For more information on applying Bloom’s taxonomy, you can find the following article on Google Scholar: Mary Forehand, “Bloom’s Taxonomy: Original and Revised,” in Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching, and Technology (Bloomington, IN: Association for Educational Communication and Technology, 2005), http://epltt.coe.uga.edu/.

ACTIVITY: Ask students to write down examples of how they can apply the knowledge they are learning in this class to the career they want after college. Also ask students to write down ways they can apply the knowledge from this class to their college life.

ACTIVITY: Divide the class into six groups. Assign each group a different level of Bloom’s taxonomy. Ask each group to create a tweet (140 characters or less) explaining their assigned level. Have each group present their tweet to the class.

Your college instructors want you to remember facts (knowledge) and understand concepts (comprehension). But they will also encourage you to apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information on tests, papers, and projects — in other words, to think critically. This book will help you practice learning at each of the six levels. For instance, later chapters provide tips on how to remember information, read textbooks strategically, take good notes, and study for exams, among other things. For now, review Table 2.2 to see examples of test questions associated with each level of learning.

CONNECT

TO MY CLASSES

Select two questions from a textbook reading or homework assignment you completed in another class this term. If possible, choose questions for which you’ve received feedback. Carefully examine each question and identify which level of learning in Bloom’s taxonomy it falls under.

| Level in Bloom’s taxonomy | Sample key words in test questions for this level | Sample test questions |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge |

who what where when choose list label match |

|

| Comprehension |

compare contrast rephrase summarize classify describe show |

|

| Application |

apply organize plan develop model solve |

|

| Analysis |

analyze categorize examine theme relationships assumptions conclusions |

|

| Synthesis |

synthesize propose predict combine adapt test discuss |

|

| Evaluation |

critique judge prove disprove opinion |

|