Think Critically to Set Goals

A goal is an outcome you hope to achieve that guides and sustains your effort over time. When you set goals, you think critically about yourself and the information you gather, using many of the skills you’ve just read about. Thus goal setting represents critical thinking in action. For instance, to set a goal, you evaluate your options. And as you work toward a goal, you analyze your progress and any obstacles facing you so that you can develop strategies for overcoming the obstacles.

Goal: An outcome you hope to achieve that guides and sustains your effort over time.

The goals you set provide a roadmap for your success — in college and in your personal and professional life. For instance, to achieve your longer-term goal of entering a particular profession, you need to meet another longer-term goal: graduating from college. And to graduate, you need to achieve shorter-term goals like passing required courses. Accomplishing these goals requires you to reach other shorter-term goals, such as completing assignments and class projects. So knowing how to use critical thinking to set and achieve your goals is vital. In this book you’ll have the opportunity to set many goals — many of them short-term ones that will support your longer-term goals.

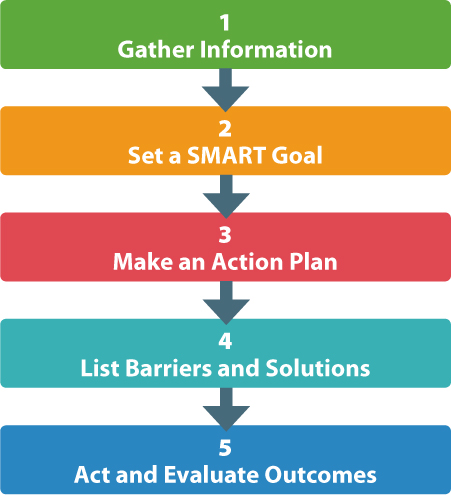

Setting any goal involves a five-step process (see Figure 2.2), and each step requires you to apply critical thinking skills. Let’s take a closer look at how the process works.

Step 1: Gather Information (about You)

The first step of goal setting isn’t actually stating your goal. Rather, it’s gathering information about yourself (like what you want to achieve and what your strengths are) so that you can define goals that are realistic and meaningful for you.

You can start by gathering information about your strengths and weaknesses. Review your ACES results and reflect on the classes you find challenging, the grades you’ve received, and past experiences you’ve had. Then consider whether you want your goal to focus on addressing a weakness or strengthening something you’re already good at. For instance, if you’re a chronic procrastinator, you may want to set a goal of improving your time-management skills. If you’re a masterful note-taker, you might want to set a goal of becoming a tutor, since teaching a skill to others often makes you even better at it yourself.

Step 2: Set a SMART Goal

Once you’ve gathered information about yourself, the next step is to set a goal that expresses what you want to achieve. Express it as a SMART goal — one that is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant to you personally, and time-limited. Avoid stating your goal in vague terms, such as “I’m going to study more” or “I want to get good grades.” Such goals are weak, because you’ll have a hard time knowing whether you’ve achieved them. (For instance, what does “to study more” actually mean?) By contrast, the SMART approach helps you create strong goals that you can realistically achieve by taking concrete steps to achieve them (see Table 2.3).

| Weak goal | SMART goal |

|---|---|

| Get good grades in class | Get a B or better in my algebra class this term |

| Spend more time studying for biology | Study my biology class notes and textbook at least five hours each week this term |

| Make some new friends | Attend a meeting of at least two on-campus clubs or organizations in the next month |

| Get some help writing my term paper | Meet with a tutor at the writing center each week for the next three weeks |

SMART Goal: A goal that is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant to you personally, and time-limited.

Specific. When you express a goal in specific terms, you know exactly what you’re trying to achieve. Contrast the specific goal “Get a GPA of 3.0 or higher this term” with the vague goal “Get good grades.” The vague goal doesn’t say what qualifies as a good grade (an A? a B+?), so you don’t have a clear idea of what you’re working toward.

CONNECT

TO MY EXPERIENCE

Think about a personal, professional, or academic goal you set but never achieved. Write down elements from the SMART goal system that might have helped you achieve your goal, and explain why they would have been useful.

ACTIVITY: Before class, create a goal that doesn’t fit the SMART criteria. Invite the class to explain why it doesn’t fit the criteria. Then, as a group, rework the goal to make it a SMART goal.

Measurable. When a goal is measurable, you know when you’ve reached it. For instance, it’s easy to determine if you’ve earned a GPA of 3.0 or higher by the end of the term. Your school calculates your GPA, so one quick look at your grades for the term tells you whether you’ve met your goal.

Achievable. Nothing is more frustrating than establishing a goal that’s beyond your reach. What is and isn’t achievable differs from person to person. For example, if you’re working full time and raising two kids while attending college, setting a goal that involves taking five classes and studying four hours a day probably isn’t achievable. On the other hand, taking one or two classes and studying one and a half hours a day on weekdays and two hours a day on weekends may be a more reasonable goal.

If you have doubts about whether a goal is achievable, consider revising your goal to increase the chances you’ll reach it. Then, once you succeed, you can set the bar higher for yourself. The key is to set goals that are challenging enough to inspire you but not so challenging that you can’t reach them.

Relevant to You. When you set goals that matter to you personally (for example, they reflect your values, interests, and career plans), you’ll be more motivated to achieve them. So if you enjoy learning about science and want to become a pharmacist, it will be easier for you to reach a goal of studying chemistry three additional hours a week. And if you plan on a career in the food services industry and believe that hunger is a pressing social problem, volunteering once a week at a food pantry would be relevant to you.

CONNECT

TO MY CAREER

Imagine that you’ve just accepted a job offer for a position in your chosen field or a field that you’re considering. Write down the name of the position and create a career goal for yourself, using the SMART criteria.

Time-Limited. SMART goals include deadlines by which you aim to achieve the goals (such as earning a GPA of 3.0 or higher by the end of the term). Take care in setting deadlines. If the deadline is too far in the future, you may procrastinate on working toward the goal. But if you set a deadline that’s too soon, the goal may start to seem unachievable, and you might feel too overwhelmed and discouraged to tackle it. Setting a time limit for achieving a goal helps you assess whether you’ve actually accomplished what you intended.

Step 3: Make an Action Plan

To achieve your goals, you need an action plan, a list of the steps you’ll take to accomplish a goal and the order in which you’ll take them. Think of your action plan as a to-do list for achieving your goal.

Action Plan: A list of steps you’ll take to accomplish a goal and the order in which you’ll take them.

Write Down Your Actions. The first step in developing a good action plan is to write down the actions you’ll take to achieve your goal. You might be tempted to make a mental list of these actions, but writing them down is a much better idea. In a recent study at Dominican University, participants who didn’t write down their goals and plans achieved only 43 percent of their goals, whereas those who wrote them down achieved more than 76 percent of their goals.6 Don’t worry about making the list perfect or recording the steps in a particular order — just write them down as they pop into your mind. For example, if your SMART goal is to submit your English term paper on the day it’s due, you might brainstorm a list of action steps like this:

ACTIVITY: Ask a student volunteer to share a personal goal that he or she is working toward, or generate a hypothetical goal yourself. As a class, create an action plan designed to meet that goal. Students will feel more comfortable with the process once they’ve had a chance to practice with their classmates.

| Action Steps |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prioritize Your Action Steps. Once you’ve brainstormed action steps and written them down, determine which steps are critical and which aren’t. (Noncritical steps are those that, if ignored, wouldn’t jeopardize your goal.) In this example, you might decide that buying a dictionary isn’t a top priority — after all, there’s one on your computer — so you cross that off the list. The items that remain should be those that are most important.

Put Your Steps in Order and Set Deadlines for Them. Once you’ve eliminated noncritical steps from your list, arrange the remaining steps in the order in which you’ll complete them. For example, if you need feedback from the writing center before editing your paper, put a visit to the writing center higher on your list. Also, add a deadline for each step so you can track your progress.

Here’s how your action plan might look now:

| Action Plan Steps (in Order) | Deadlines |

|---|---|

| 1. Schedule appointment with writing tutor | This Friday |

| 2. Prepare rough draft of term paper | Three weeks before due date |

| 3. Submit rough draft to writing tutor | Same day as above |

| 4. Incorporate feedback from writing tutor into final version | Within one week of due date |

| 5. Submit final term paper | On due date |

THE ACADEMIC BENEFITS OF GOAL SETTING

spotlight onresearch

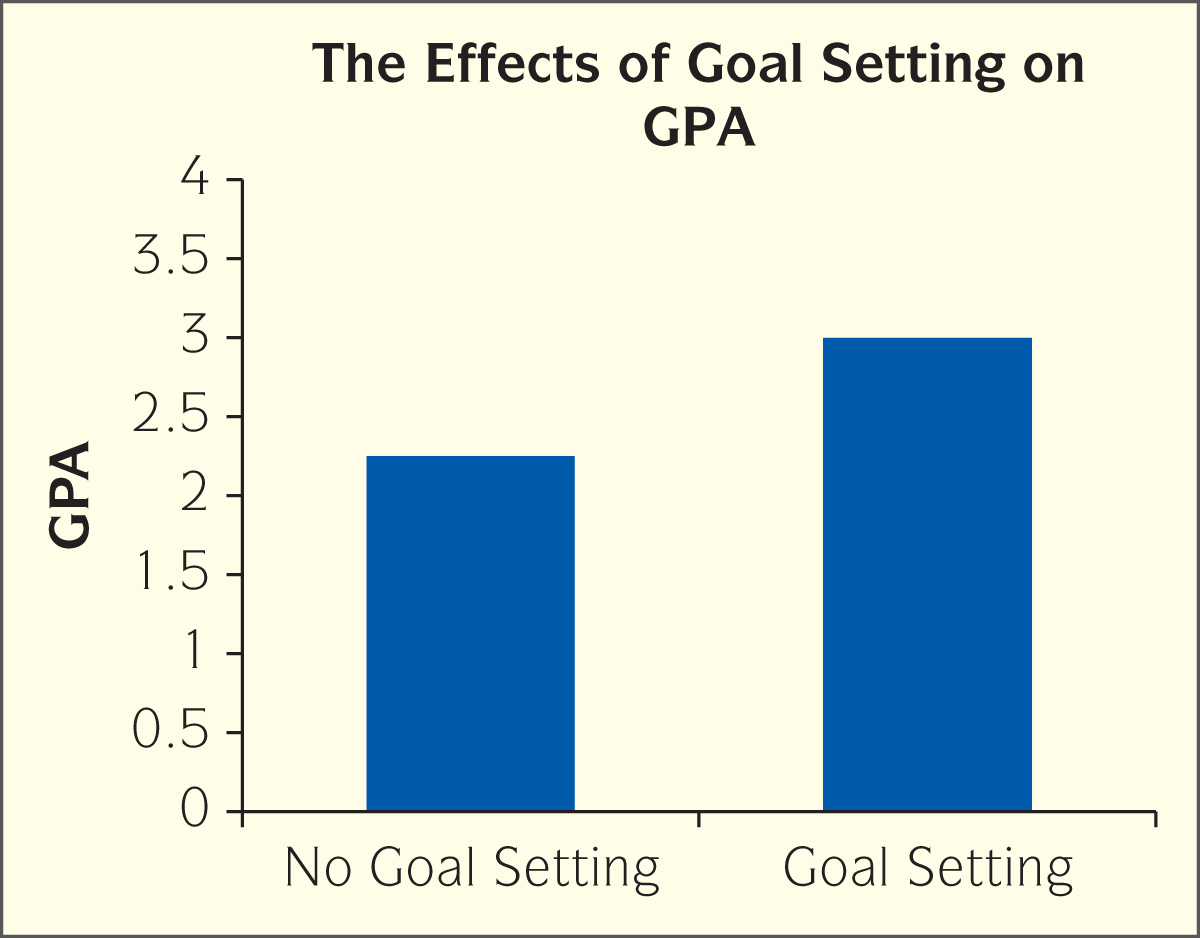

Hundreds of research studies have established the importance of goal setting in the workplace. Recently, a group of researchers conducted a study to see if goal setting also promotes college success. They took eighty-five undergraduate students who were having trouble with their studies and divided them into two groups:

Group 1: These students completed surveys measuring their career interests, curiosity, and initiative. They also listed past accomplishments that they were proud of. They received no training on setting and achieving goals.

Group 2: These students participated in a Web-based program introducing them to a process for setting and achieving personal goals. They wrote down seven or eight goals, prioritized them, and described how meeting those goals would improve their lives.

On average, students in group 1 achieved GPAs of 2.25. On average, those in group 2 achieved GPAs of almost 3.0. They also completed more academic credits. And compared to the group 1 students, they said they felt less anxious, less stressed, and more satisfied with life.

THE BOTTOM LINE

When you learn how to set goals, you’ll likely improve your grades, feel more satisfied with your life, and achieve more of your goals.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Question 2.1

1. How often do you write down your goals and the steps needed to achieve them?

Question 2.2

2. Do you ever stop to evaluate your progress toward your goals? Why or why not?

Question 2.3

3. Which of the five SMART criteria do you think will be the most difficult to follow in defining your goals?

D. Morisano, J. B. Hirsh, J. B. Peterson, R. O. Pihl, and B. M. Shore, “Setting, Elaborating, and Reflecting on Personal Goals Improves Academic Performance,” Journal of Applied Psychology 95 (2010): 255–64.

Step 4: List Barriers and Solutions

CONNECT

TO MY RESOURCES

Write down two barriers that might prevent you from achieving your goals this term. Then list at least two resources on campus or in your community that could help you overcome these barriers.

Even when you have an action plan for achieving a goal, you can still encounter barriers. A barrier is something that prevents you from making progress toward your goal. It might be a personal characteristic (like a tendency to procrastinate) or something in your environment (like too many family commitments). Some barriers (such as poor time management) are under your control. With others (like family or work demands), you might have less control.

Barrier: A personal characteristic or something in your environment that prevents you from making progress toward a goal.

As you set your goals, write down the types of barriers you may face. By acknowledging potential barriers, you won’t get blindsided if you actually encounter them. Also, you can brainstorm in advance how to overcome them. For example, suppose you’re worried that your job will get very busy during midterms and interfere with your study time. By anticipating this barrier, you can figure out ways to avoid it — such as trading hours with a coworker.

And remember that you don’t have to face barriers alone. Many helpful resources are available to provide support and encouragement. Faculty members, tutors, and academic and career advisers, for example, can work with you to overcome common barriers. To get help, you just have to ask.

Step 5: Act and Evaluate Outcomes

As you start taking the steps in your goal-setting action plan, regularly evaluate your progress. Are the steps you’re taking effective? Are you completing them on time? Are they helping you get closer to meeting your goal? If you’re not making the progress you’d hoped for, evaluating your outcomes helps you know this immediately so that you can change your action plan or find resources to get you back on track. Also, evaluation can help you stay motivated to keep working toward your long-term goals. By recording and celebrating your progress on the short-term goals that support your long-term ones, you build up proof that you’re getting closer to your long-term goals.

If your evaluation shows that you’ve experienced a setback, stay positive. The point of evaluating your progress is to identify and deal with setbacks. Each time you do so, you’ll get even better at achieving your goals, and you can seek out help if you need it. Remember: Setting and achieving goals takes practice. You didn’t learn how to ride a bike on the first try either!

ACTIVITY: As a class, create a list of barriers that may impede finishing college. Fill the entire whiteboard. Next, ask the class to suggest solutions to these barriers. As a solution is found, erase the barrier. When the board is empty, explain that even though barriers look overwhelming, they can be overcome.

voices of experience: student

FOCUSING ON SOLUTIONS

| NAME: | Thamara Jean |

| SCHOOL: | Broward College |

| MAJOR: | Pre-Nursing |

| CAREER GOAL: | Nursing |

“Making mistakes doesn’t mean failure, unless you fail to learn from your mistakes.”

Since I was seven years old, I’ve wanted to be a doctor — I think my goal was influenced by my parents and from watching lots of doctor shows on TV. With that goal in mind, I arrived at college and really struggled with courses like organic chemistry and pre-calculus. It wasn’t until I attended a required advising meeting that I realized I wasn’t thinking very critically about my goal. I didn’t have much information about what was required to get through pre-med and medical school. I realized that semester that choosing medicine was probably a mistake but that making mistakes doesn’t mean failure, unless you fail to learn from your mistakes. My adviser and I discussed creating a backup plan that included switching to pre-nursing, getting experience in health care settings, and continuing to gather information about medical school.

That same semester I attended a leadership and goal-setting workshop where I learned about SMART goals and was encouraged to get more involved in campus leadership activities. It was part of a campus initiative called QEP — Questioning Every Possibility. I learned to question, assess, analyze, and even research everything, because my future depends on me!

I immediately set a number of specific goals, like joining Phi Theta Kappa and the campus Honors Committee, passing my classes the next semester, and researching information about how to get into nursing school. To support my goal of passing classes, I set additional goals like getting tutoring in math and science and getting feedback on my papers before submitting them in literature classes. I feel back on track. I recently transferred to Florida Atlantic University, where I’m applying for acceptance into the nursing program, and I’m looking forward to a successful career in nursing.

YOUR TURN: Have you ever set a goal and then discovered significant barriers blocking your way? If so, what did you do to overcome those barriers or adjust your goal to make it more realistic?