Overcome Procrastination and Minimize Distractions

If you’re like most people, you sometimes put off getting down to work. You check Twitter one more time, send a text — do anything except what you’re supposed to be doing. In short, you procrastinate. When you procrastinate, you open yourself up to distractions — events or objects in your environment that take your attention away from the task you need to complete.

Procrastinate: To delay or put off an action that needs to be completed.

Procrastination and distractions can undo all the effort you’ve put into getting organized and taking control of your time. So the next time you find yourself procrastinating or getting distracted, use your critical thinking skills. Ask yourself: “Why am I putting off this task?” or “Why am I not focusing on what I should focus on?” The more you know about what’s causing you to fall victim to procrastination or distractions, the more you can work to change your behavior so that you can accomplish your goals.

Beat Procrastination

People procrastinate for various reasons. By understanding the most common root causes, which we’ll explore in the section that follows, you can identify when you’re falling victim to these causes — and apply the right antidotes.

Low Motivation. If you don’t feel motivated to complete a task, you might be tempted to procrastinate. Fight low motivation with these tactics.

CONNECT

TO MY EXPERIENCE

Think about a time when you overcame procrastination. Write down why you were procrastinating and what you did to refocus on the task at hand. Identify how you could use this same strategy to combat procrastination in school.

Engage in self-reflection. You may feel unmotivated because you lack a sense of self-efficacy regarding the task at hand, you don’t see it as relevant to you, or you have a negative attitude about your studies in general. (See the chapter on motivation, decision making, and personal responsibility.) Try to identify which of these three key ingredients of motivation you’re missing. Sometimes simply understanding why you’re unmotivated can spur you to take action.

Just get started. If you have reading to do, pick up your textbook and begin. If you have to do research for a paper, log on to the library’s Web site, and start searching for articles. In some cases, just telling yourself it’s time to work will revive your motivation.

Move. Grab your materials, go somewhere new, and clear your head. Physical motion may be enough to motivate you to focus on the work you need to do.

Perfectionism. Some people avoid starting projects because they want to achieve a perfect result and worry that they won’t be able to. If this happens to you, try these strategies to combat perfectionism.

Reframe your expectations. Give yourself permission to let go of perfectionistic thinking. Instead of telling yourself that everything you work on must be perfect, tell yourself that you’ll put your best effort into each project or task.

Start small. Complete some small tasks related to the work you’re procrastinating on; then use your success to gain momentum for finishing another set of tasks. Eventually, you’ll complete the whole project.

FURTHER READING: For more tips on how to stop procrastinating, visit Unstuck.com and search for the article “How We Procrastinate (and May Not Even Know It).” Unstuck also has a free app that students can download directly to their smartphones.

Feeling Overwhelmed. If you feel overwhelmed by the amount of work facing you, it may be daunting just to get started. Try these tactics to keep moving forward.

Be realistic. Remind yourself that you can’t do everything at once and that every journey — however long or short — starts with a single step. Then pick a place to start.

Trick yourself. Tell yourself that you’re going to read or write for only ten minutes or that you’ll read or write only three pages. Once you get involved in the work, you may look up forty-five minutes later and discover that you’re almost finished — and that’s a good reason to keep going.

Minimize Distractions

Distractions can be a big challenge for some students, causing them to veer off track. If you intend to study chemistry for two hours but then spend an hour online watching videos of cute cats, you’ll lose time you can’t get back. To protect yourself against distractions, consider these tips.

ACTIVITY: Ask students to identify possible schedule busters. Once you have a large list, brainstorm ways to avoid these distractions. For example, if one schedule buster is mindless Web surfing, have students find an app that can lock down the Internet for a period of time, removing the distraction.

FURTHER READING: For a closer look at why distractions can be so powerful and how to combat them, refer to the article “Five Reasons We Can’t Stop Distracting Ourselves,” written by Joanne Cantor, Ph.D. (Psychology Today, July 16, 2012).

Find strength in numbers. With your roommates or family members, agree on a time when everyone focuses on coursework (or schoolwork for your kids) or other quiet tasks. Doing so creates an environment of support and accountability: When everyone around you is studying or working quietly, you’ll find it easier to stay focused.

Use the “off” switch. Turn off the television, your phone, and any other devices that create visual or auditory distractions. Log out of Facebook, Twitter, and other social networking sites. Click the setting that turns off that annoying little chime that lets you know you’ve just received an e-mail. As you plan your study time, allow five minutes each hour to check these devices and respond to messages. That way, you won’t feel tempted to do so while you work.

Block out other sources of distraction. For example, close the curtains or pull down the shades in your room so you can’t see what’s happening outside. If your neighbor is playing loud music, invest in a set of earplugs to block out the noise.

GET IN THE ZONE: IT FEELS GOOD!

spotlight onresearch

Have you ever had the experience of being “in the zone,” or fully present while completing a task? If so, you were probably in a mental state of flow. You have this experience when you’re completely immersed in a task that you consider enjoyable, such as playing a musical instrument, studying, playing sports, praying, or playing video games. Flow involves concentration and reduced self-consciousness. People in a state of flow feel as though they’re in control, and they often lose track of time. In his book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi explains that individuals experience flow when they possess the skill needed to complete a task and find the experience challenging and intrinsically rewarding. When you eliminate distractions around you, you can help create the optimal conditions for flow.

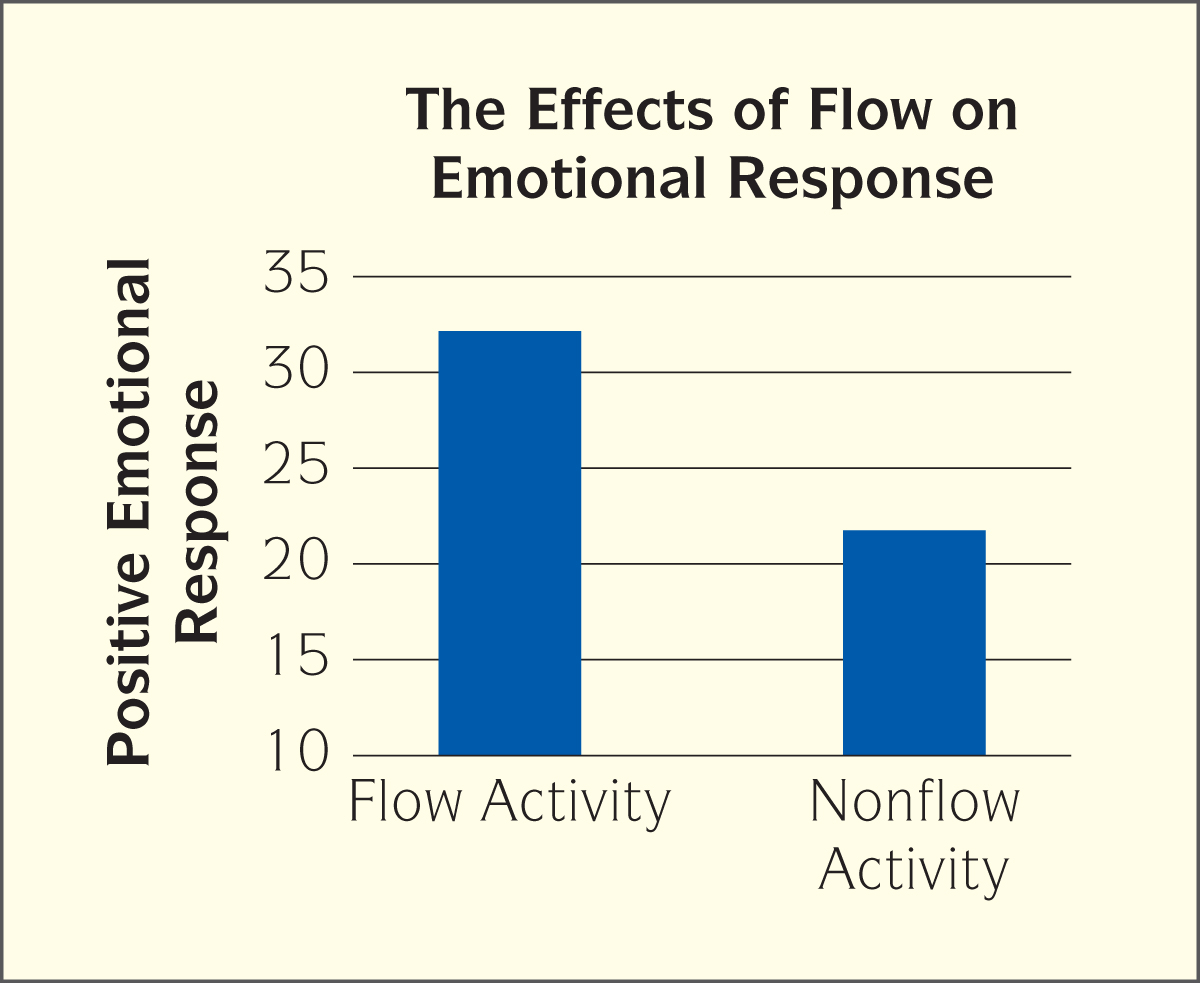

A recent study examined college students’ experience of flow and the impact on their emotions.

Half of the fifty-seven student participants were asked to identify a positive, focused activity they enjoyed (a flow activity) and to engage in that task once during a two-week period.

The other half of the students were asked to identify an everyday activity (a nonflow activity) and to participate in the task.

All the students recorded their experience of flow and their emotions before and after the activity.

Interestingly, the two flow activities chosen by the greatest number of students in this research were exercising and going to class/studying. The students who engaged in a flow activity experienced more positive emotions than did students who engaged in everyday activities. The more intense the flow experience, the greater the positive feelings.

THE BOTTOM LINE

You can get into a state of flow when you study. To do so, find something in your coursework that interests you, minimize distractions, and completely immerse yourself in that material. Not only will you learn, but you’ll also feel good.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Question 5.1

1. Have you ever experienced flow? If so, what were you doing at the time?

Question 5.2

2. What might prevent you from entering a state of flow?

Question 5.3

3. What could help you get “in the zone” while you study so you’re not tempted to procrastinate?

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper & Row, 1990).

T. P. Rogatko, “The Influence of Flow on Positive Affect in College Students,” Journal of Happiness Studies 10 (2009): 133–48.