Do-It-Yourself Studying: Create Your Own Study Tools

Mastering the basic study strategies described in the previous section is a great first step. As a next step, we focus on how to create your own study tools — an approach that helps you learn and gives you flexibility in how you study. You’ve spent hours sitting in class or responding to posts online, reading your textbooks, and taking countless pages of notes. When you create your own study tools, you bring all these efforts together to learn on a deeper level, strengthening your comprehension. Creating study tools is like using your working memory to encode information into your long-term memory: You actively process course material to make new memories, which you can use later on tests and projects. So take a look at the tools described in this section, and find the ones that interest you most.

ACTIVITY: Divide the class into groups, and assign each group one of the study tools presented in this section. Give the class a short article to read about a current event, and have each group create its assigned study tool using information from the article. Have the groups present their tool to the class and explain why they believe the tool is effective.

Write Flash Cards

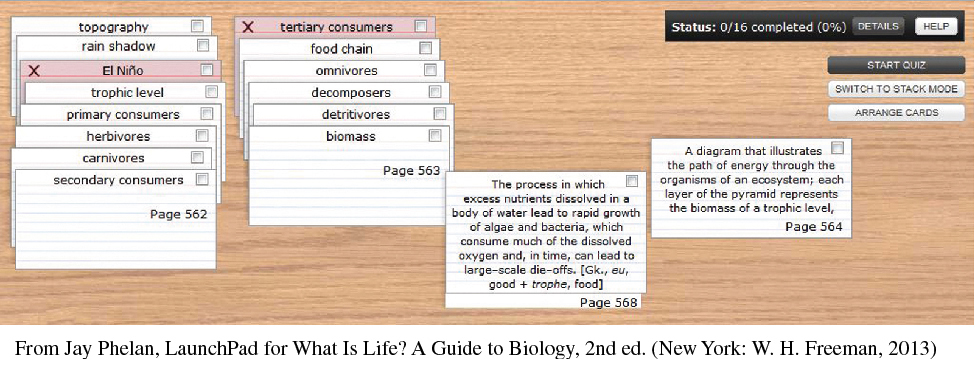

If you want a study system you can take anywhere, try creating flash cards. You can make these from paper note cards or even use a flash card app on your computer or phone (see Figure 8.2). Flash cards are a blank slate — you can put anything you want on them. For instance, you can put key words on one side of the card and definitions on the other, or write historical events on one side and the dates when they occurred on the reverse side. You can also use them to quiz yourself on broad concepts, themes, or theories.

How do flash cards help you remember? For some people, the act of writing helps the concepts stick. In addition, as you flip through the flash cards over and over, you use rote rehearsal; in other words, you memorize specific information or facts by studying the information repeatedly. This approach is valuable when you need to remember specific facts, such as the parts of the human body or mathematical formulas. In general, flash cards are less useful when you need to demonstrate comprehension of more complex information, such as how the Ottoman Empire changed from the thirteenth to seventeenth centuries. So, for a well-rounded study strategy, use flash cards in addition to other techniques in this chapter.

Rote Rehearsal: Memorization of specific information or facts by studying the information repeatedly.

As you use your flash cards to study, keep these tips in mind.

Shuffle the cards regularly and review them multiple times. Recognizing the content one time won’t help you master it.

Go through the cards twice a day for the entire week before an exam.

If you find yourself flipping through the cards mindlessly, set them aside for a few minutes and come back to them when you can stay focused.

Create Review Sheets

As you record information from lectures and reading assignments, you’ll find yourself building up mounds of pages and stacks of bulging notebooks. To manage all this information, try creating a review sheet by condensing pages of detailed notes into a one-page document. When you condense material, you include only the information you really need — such as the main ideas from your notes, annotations you made while reading a textbook chapter, problems from your math class, or dates from your history class. Give yourself some flexibility, though: If one page is too limiting, create a separate review sheet for each chapter that will be covered on a test. You can also share and compare your review sheets with classmates, and each person can offer ideas for improving them and filling in gaps.

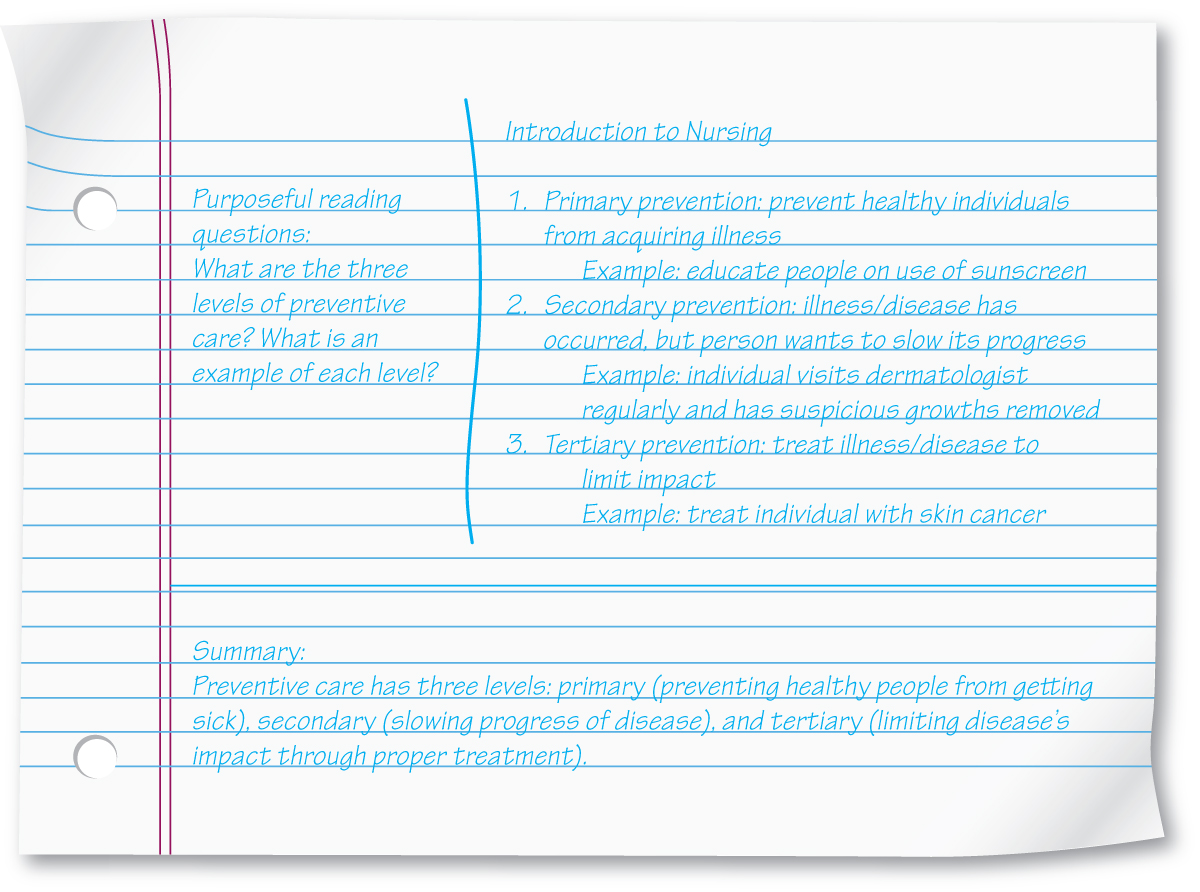

Use Purposeful Reading Questions

If you’ve created and answered purposeful reading questions while taking notes on a textbook chapter or other reading assignment (see the reading chapter), you have a ready-made study tool. Review the questions in your notes, cover up the answers, and answer the questions out loud to yourself or with a study partner. Or combine your purposeful reading questions with other study tools. You might make flash cards with a question on one side and the answer on the other. If you like the Cornell notes system, write your questions in the cue column on the left and your answers in the notes section on the right; then use the summary section at the bottom to restate in your own words the key ideas you want to remember (see Figure 8.3).

ANSWER PRACTICE QUESTIONS — IT WORKS!

spotlight onresearch

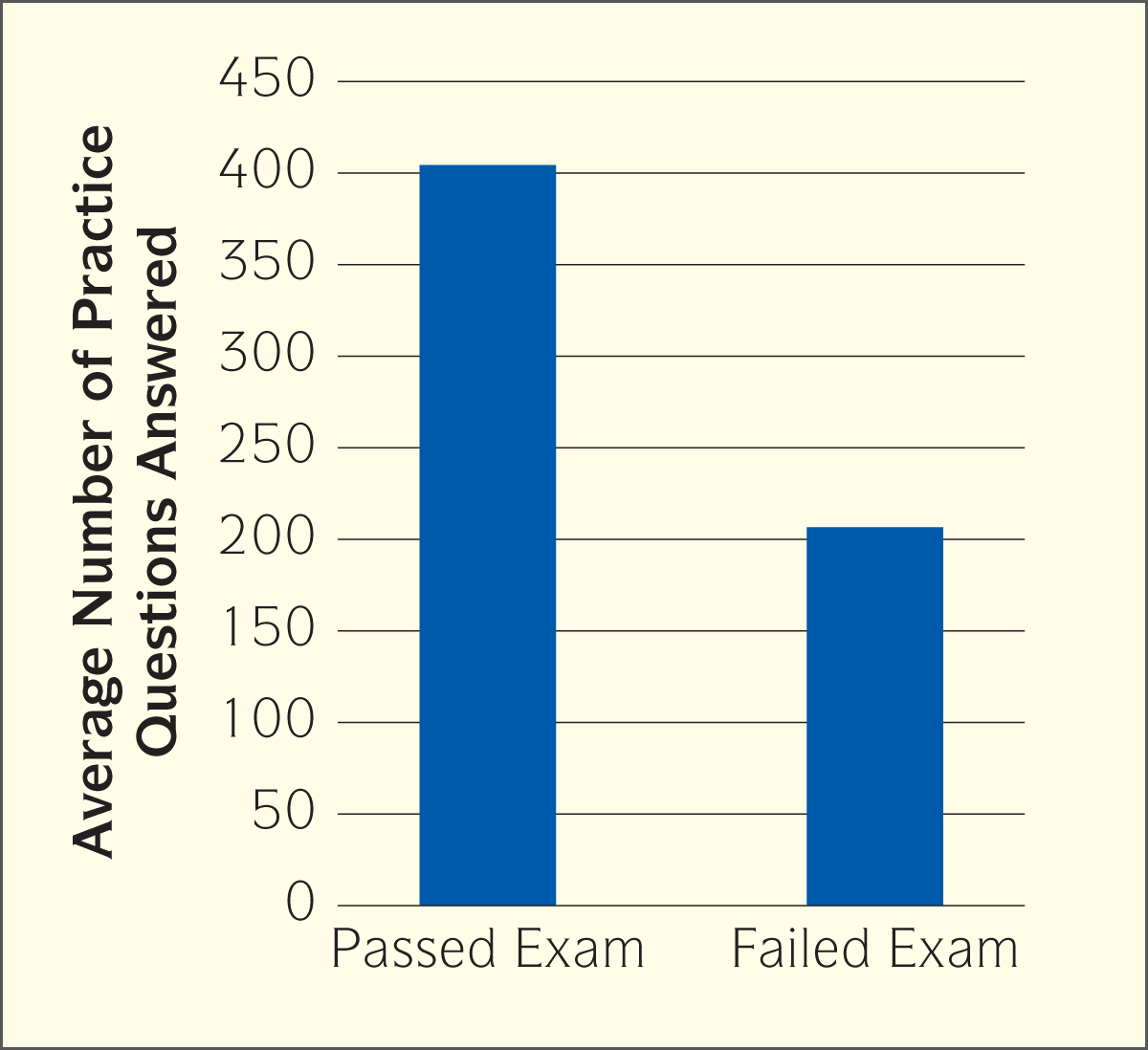

At the end of each chapter, many textbooks provide study or practice questions (which you can use as purposeful reading questions). Two Dutch researchers examined the impact of these questions on students’ performance in a psychology class. The researchers gave 201 students more than five hundred questions to help them plan their study time and prepare for an exam at the end of the class. These were short-answer essay questions, designed to help students focus on the main topics from their reading — for example, “What are the basic components of the central nervous system?” and “What causes Down syndrome?” At the end of the class, the researchers examined the relationship between the number of study questions the students answered and how they performed on the final exam. They found the following:

Only 51 percent of the students passed the exam.

The students who passed answered an average of 81 percent of the five hundred study questions before taking the exam.

The students who failed answered an average of 41 percent of the study questions before taking the exam.

The researchers also asked the students how the questions were helpful. The students said that the study questions helped them plan their studying, better understand the course material, and prepare for the exam.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Answering more practice questions before taking an exam can help you pass the exam.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

Question 8.1

1. How often do you use the practice questions included in your textbooks to study for tests? Have you found these practice questions helpful?

Question 8.2

2. Have you ever created your own study questions? If so, how did they work for you?

Question 8.3

3. Will you use practice questions to study for tests in the future? Why or why not?

P. Wilhelm and J. M. Pieters, “Fostering Effective Studying and Study Planning with Study Questions,” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 32 (2007): 373–82.

Create Practice Tests

Creating your own practice test is a powerful way to prepare for an exam. When you write your own test questions, you think about the exam topics in detail — and that can help you deepen your understanding of the material and commit it to memory. To create a practice test, first figure out the most important information you’ll need to know for the exam. Use your critical thinking skills to evaluate all the information from class lectures and reading assignments, and decide which information matters most. To do this, review your notes from class, your textbook, and notes you took while reading. And don’t forget to look over any purposeful reading questions you created — these are a great place to start.

ACTIVITY: Divide the class into groups, and give each group ten to fifteen minutes to create a practice test for the previous chapter in this book. After writing their tests, have the groups exchange tests, and give each group ten to fifteen minutes to take the test. Then, as a class, discuss how creating a practice test could help in retaining information.

Once you’ve identified the key topics, create questions that focus on these areas. You might create matching questions for dates and events in history class, essay questions for economics class, multiple-choice questions for accounting or biology, and practice problems for chemistry or math. Create answers for each question. Finally, trade test questions with classmates and challenge one another to answer them. As you answer more and more questions correctly, you’ll build up your confidence in the material.

Draw a Mental Picture

Another way to use your working and long-term memory is to visualize, or create a mental picture, of the material you’re studying. Start by looking at the image you want to re-create in your mind. It might be a figure from your chemistry text showing the molecular formula for benzene, or the parts of a blueprint for your construction course. Cover up the original image and try to picture what it looks like in your mind. Then look back at the actual image: How well does your mental picture match the image? Repeat this activity until the image in your mind matches the image you see on the page.

Use Mnemonics

If you want to memorize specific material you can create a mnemonic (pronounced “neh mon ik”), which is a trick or strategy to remember information. For example, the rhyme “Thirty days hath September, April, June, and November …” is a mnemonic for remembering the number of days in each month. Mnemonics help you remember specific information you need to recall for an exam or to solve a problem. Creating a mnemonic requires critical thinking, as well as some creativity. Try the following popular mnemonic strategies.

Mnemonic: A learning strategy that helps you memorize specific material.

FOR DISCUSSION: In class, ask students to list as many mnemonics as they can remember. Where did they learn these mnemonics? What do they stand for? Did students name different mnemonics for remembering the same information?

Acronyms. Make an acronym, a word created from the first letter of each word you want to remember. For example, the acronym HOMES can help you remember the five Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior). In your Introduction to Psychology class, the acronym OCEAN can help you remember the five major personality traits (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism). In this class, the acronym SMART can help you remember the steps of the goal-setting process (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-limited).

Associations. Create associations between new information and things you already know. Let’s say you want to memorize a list of Greek gods for your art history course. You start with Zeus, king of the gods, whom you associate with your uncle, who happens to be a large and powerful man. Zeus’s wife, Hera, you associate with your aunt Helen. (Both names start with H, which is easy for you to remember.) Next you associate Ares, the son of Zeus and Hera, with your cousin. You might take the association even further and imagine how all of these gods would interact at your family reunion. As you create these associations, you’re practicing elaborative rehearsal and building long-term memories of this new information.

Method of Loci. Associate words you need to remember with locations that are familiar to you. For instance, suppose you’re trying to remember the sequence of early U.S. presidents. You could associate each president with the sequence of actions you perform while getting from your apartment to school. You wake up and say good morning to George Washington (the first president), whom you imagine sitting on your dresser. Next you see John Adams (the second president) at the breakfast table. Then you greet Thomas Jefferson (the third president) as you leave your apartment. Finally, you see James Madison (the fourth president) at the end of your driveway. The memory links you choose don’t have to make sense. In fact, it’s better if they’re funny, outrageous, or off-the-wall: They’ll capture your attention, making them easier to remember.

Acrostics. An acrostic is a phrase or sentence in which the first letter of every word corresponds to a list of words you want to remember. Acrostics are especially useful when you want to memorize words in a particular order. Some common acrostics are “Every Good Boy Does Fine” (E, G, B, D, F) for lines on the treble clef, or “Kids Prefer Cheese Over Fried Green Spinach” (kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species) for the order of taxonomy in biology. Can you think of what the acrostic “My Very Energetic Mother Just Served Us Nachos” represents? Here’s a hint: We all live on “E.”

voices of experience: student

USING STUDY TOOLS TO SUCCEED

| NAME: | James Lawrence |

| SCHOOL: | Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College |

| MAJOR: | Psychology |

| CAREER GOAL: | Clinical Psychologist |

“You have to think of your brain as a muscle — if you don’t challenge it, it will become weaker!”

When I first started junior college, I was nervous about my classes and really didn’t know what to expect from my professors. I had heard that college was harder than high school and required more studying — something my mama called “burning the midnight oil.” I honestly didn’t know how to study because in high school I never had to. I just went to class, listened to the teacher’s lecture, completed my worksheets, and passed the test.

It was the second week of classes when the difference between high school and college really sank in. I realized that there were no more worksheets and that just attending class wasn’t going to allow me to succeed. Most of my classes included four exams — each covering material from up to six chapters — and I needed to do more than just memorize the material in all those chapters. I panicked, then made friends in each of my classes. We formed study groups, and in those groups I picked up some new strategies for learning. Some students in the group used flash cards to help them study, and others would review their notes repeatedly or make their own test questions to practice understanding the material.

Making flash cards worked best for me because it made me act on the material rather than just reading it over and over. I had to identify and write a concept on one side of the card and write the explanation on the other side. Having to write the material down was a concrete way for me to interact with the content. Then I could quiz myself using the cards no matter where I was on campus. You have to think of your brain as a muscle — if you don’t challenge it, it will become weaker!

YOUR TURN: Have you ever created flash cards? If so, how well did this study tool work for you? What were the advantages? The challenges?