12.1 Infancy: Using Caregivers as a Base for Growth

In the mid-twentieth century, the psychoanalytically oriented child psychologist Erik Erikson (1963) developed an elaborate theory of social development. The theory posited that each stage of life is associated with a particular problem or set of problems to be resolved through interactions with other people. It also posited that the way the person resolves each problem influences the way he or she approaches subsequent life stages. In infancy, according to Erikson, the primary problem is that of developing a sense of trust—that is, a secure sense that other people, or certain other people, can be relied upon for care and help.

462

Other theorists, too, have focused on the infant’s need for care and on the psychological consequences of the manner in which care is provided. One such theorist was John Bowlby, a British child psychologist who, in the mid-twentieth century, brought an evolutionary perspective to bear on the issue of early child development. Bowlby (1958, 1980) contended that the emotional bond between human infant and adult caregiver—especially the mother—is promoted by a set of instinctive tendencies in both partners. These include the infant’s crying to signal discomfort, the adult’s distress and urge to help on hearing the crying, the infant’s smiling and cooing when comforted, and the adult’s pleasure at receiving those signals.

Human infants are completely dependent on caregivers for survival, but, consistent with Bowlby’s theory, they are not passively dependent. They enter the world biologically prepared to learn who their caregivers are and to elicit from them the help they need. By the time they are born, babies already prefer the voices of their own mothers over other voices (discussed in Chapter 11), and shortly thereafter they also prefer the smell and sight of their own mothers (Bushnell et al., 1989; Macfarlane, 1975). Newborns signal distress through fussing or crying. By the time they are 3 months old, they express clearly and effectively their interest, joy, sadness, and anger through their facial expressions, and they respond differentially to such expressions in others (Izard et al., 1995; Lavelli & Fogel, 2005).

Through such actions, infants help build emotional bonds between themselves and those on whom they most directly depend, and then they use those caregivers as a base from which to explore the world. In the 1950s, Bowlby began to use the term attachment to refer to such emotional bonds, and since then the study of infants’ attachment to caregivers has become a major branch of developmental psychology.

Attachment to Caregivers

At about the same time that Bowlby was beginning to write about attachment, Harry Harlow initiated a systematic program of research on attachment with rhesus monkeys. Harlow controlled the monkeys’ living conditions experimentally to learn about the developmental consequences of raising infants in isolation from their mothers and other monkeys. Most relevant to our present theme are experiments in which Harlow raised infant monkeys with inanimate surrogate (substitute) mothers.

Harlow’s Monkeys Raised with Surrogate Mothers

1

What was Harlow’s procedure for studying attachment in infant monkeys, and what did he find?

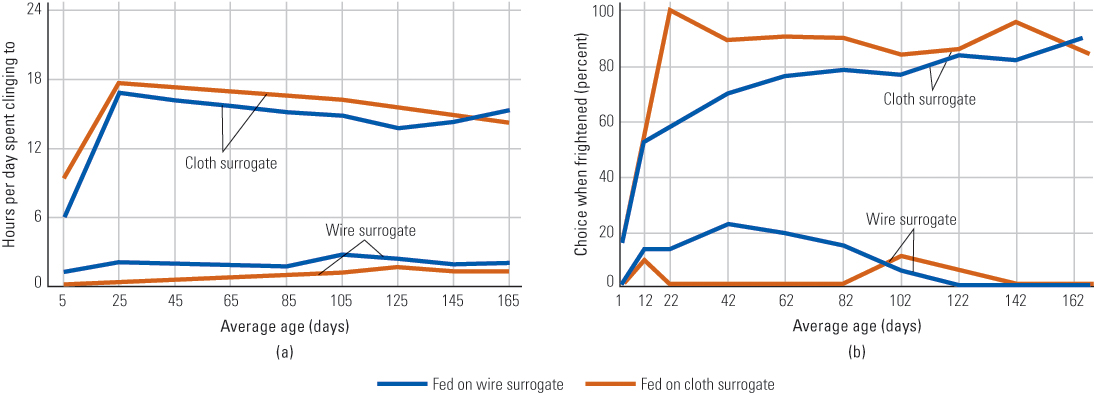

In one experiment, Harlow raised infant monkeys individually in isolated cages, each containing two surrogate mothers—one made of bare wire and the other covered with soft terry cloth (see Harlow & Zimmerman, 1959; Figure 12.1). The infants could feed themselves by sucking milk from a nipple that was affixed either to the wire surrogate or to the cloth surrogate. Harlow’s purpose was to determine if the infants would become attached to either of these surrogate mothers as they would to a real mother; he also wanted to know which characteristic—the milk-providing nipple or the soft cloth exterior—was most effective in inducing attachment.

463

Harlow’s main finding was that regardless of which surrogate contained the nutritive nipple, all the infant monkeys treated the cloth-covered surrogate, not the wire one, as a mother. They clung to it for much of the day and ran to it when frightened by a strange object (see Figure 12.2). They also were braver in exploring an unfamiliar room when the cloth surrogate was present than when it was absent, and they pressed a lever repeatedly to look at it through a window in preference to other objects. This work demonstrated the role of contact comfort in the development of attachment bonds, and it helped to revolutionize psychologists’ thinking about infants’ needs. Providing adequate nutrition and other physical necessities is not enough; infants also need close contact with comforting caregivers.

The Form and Functions of Human Infants’ Attachment

2

According to Bowlby, what infant behaviors indicate strong attachment, and why would they have come about in natural selection?

Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) observed attachment behaviors in young humans, from 8 months to 3 years of age, that were similar to those that Harlow observed with monkeys. He found that children showed distress when their mothers (the objects of their attachment) left them, especially in an unfamiliar environment; showed pleasure when reunited with their mothers; showed distress when approached by a stranger unless reassured or comforted by their mothers; and were more likely to explore an unfamiliar environment when in the presence of their mothers than when alone. Many research studies have since verified these general conclusions (Thompson, 2013).

Bowlby contended that attachment is a universal human phenomenon with a biological foundation that derives from natural selection. Infants are potentially in danger when out of sight of caregivers, especially in a novel environment. During our evolutionary history, infants who scrambled after their mothers and successfully protested their mothers’ departure, and who avoided unfamiliar objects when their mothers were absent, were more likely to survive to adulthood and pass on their genes than were those who were indifferent to their mothers’ presence or absence. Evidence that similar behaviors occur in all human cultures (Kagan, 1976; Konner, 2010) and in other species of mammals (Kraemer, 1992) supports Bowlby’s evolutionary interpretation.

3

From an evolutionary perspective, why does attachment strengthen at about 6 to 8 months of age?

Also consistent with the evolutionary explanation is the observation that attachment begins to strengthen at about the age of 6 to 8 months, when infants begin to move around on their own. A crawling or walking infant—who for good evolutionary reasons is intent on exploring the environment—can get into more danger than an immobile one. For safety’s sake, exploration must be balanced by a drive to stay near the protective caregiver. As was noted in Chapter 11, infants who can crawl or walk exhibit much social referencing; that is, they look to their caregivers for cues about danger or safety as they explore. To feel most secure in a novel situation, infants require not just the presence of their attachment object but also that person’s emotional availability and expressions of reassurance. Infants who cannot see their mother’s face typically move around her until they can (Carr et al., 1975), and infants who are approached by a stranger relax more if their mother smiles cheerfully at the stranger than if she doesn’t (Broccia & Campos, 1989).

464

The Strange-Situation Measure of Attachment Quality

4

How does the strange-situation test assess the security of attachment?

In order to assess attachment systematically, Mary Ainsworth—who originally worked with Bowlby—developed the strange-situation test. In this test the infant and mother (or another caregiver to whom the infant is attached) are brought into an unfamiliar room with toys. The infant remains in the room while the mother and an unfamiliar adult move out of and into it according to a prescribed sequence. The infant is sometimes with just the mother, sometimes with just the stranger, and sometimes alone.

Infants in this test are classed as securely attached if they explore the room and toys confidently when their mother is present, become upset and explore less when their mother is absent (whether or not the stranger is present), and show pleasure when the mother returns. Other response patterns are taken to indicate one or another form of insecure attachment. An infant who avoids the mother, acts indifferent to the mother when she leaves, and seems to act coldly toward her is said to have an avoidant attachment; and an infant who does not avoid the mother but continues to cry and fret despite her attempts to comfort is said to have an anxious attachment. By these criteria, Ainsworth and other researchers have found that about 70 percent of middle-class North American infants in their second year of life are securely attached to their mothers, about 20 percent are avoidant, and about 10 percent are anxious (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Waters et al., 2000).

Like most measures of psychological attributes, the strange-situation test has limitations. The test assesses fear-induced aspects of attachment, but fails to capture the harmonious caregiver–child interactions that typically occur in less-stressful situations (Field, 1996). Moreover, the test is designed to assess the infant’s reactions to the caregiver in a mildly fearful situation, but for some infants, because of temperament or past experience, the situation may be either too stressful or insufficiently stressful to induce the appropriate responses.

Sensitive Care Correlates with Secure Attachment and Positive Later Adjustment

5

What evidence suggests that sensitive parenting correlates with secure attachment and subsequent emotional and social development? How did Ainsworth interpret the correlations, and how else might they be interpreted?

Ainsworth hypothesized that infants would become securely attached to mothers who provide regular contact comfort, respond promptly and helpfully to the infant’s signals of distress, and interact with the infant in an emotionally synchronous manner—a constellation of behaviors referred to today as sensitive care. Consistent with that hypothesis, Ainsworth, and other researchers subsequently, found significant positive correlations between ratings of the mother’s sensitive care and security of the infant’s attachment to the mother (Ainsworth, 1979; Posada et al., 2004; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997). In most such studies, the mother’s style of parenting was assessed through home visits early in infancy, and attachment was assessed with the strange-situation test several months later, after the baby could move about on his or her own.

Ainsworth (1989) also predicted that secure attachment would lead to positive effects later on in life. This view was very much in line with that of Bowlby (1973), who postulated that infants develop an internal “working model,” or cognitive representation, of their first attachment relationship and that this model affects their subsequent relationships throughout life. It was also consistent with Erikson’s (1963) theory that secure attachment in infancy results in a general sense of trust of other people and oneself, which permits the infant to enter subsequent stages of life in a confident, growth-promoting manner. Consistent with such views, children judged to be securely attached in infancy have been found, on average, to be more confident, better at solving problems, emotionally healthier, and more sociable later in childhood than those who had been found to be insecurely attached (Ainsworth, 1989; Raikes & Thompson, 2008; Schneider et al., 2001).

465

6

What experimental evidence supports the theory that sensitive care promotes secure attachment?

How do we know that maternal sensitivity is truly causing infants to become securely attached to their mothers, rather than some third factor such as infant temperament? Several studies in which parents were trained to interact with their infants in a certain way provide an answer. In one such study, mothers with temperamentally irritable babies—babies who by disposition are unusually fussy, easily angered, and difficult to comfort—participated in a 3-month training program, beginning when their infants were 6 months old, designed to help and encourage the mothers to perceive and respond appropriately to their babies’ signals, especially signals of distress. When the infants were 12 months old, all of them were tested with their mothers in the strange-situation test. The result was that 62 percent of the infants with trained mothers showed secure attachment, versus only 22 percent of the infants in a control condition who did (van den Boom, 1991). Other experiments have shown that parental training for foster parents can result in more sensitive parenting, more secure attachment, reduced physiological evidence of distress in the child, and fewer reported problem behaviors in the child (Dozier et al., 2006; Fisher et al., 2006).

Some Children Are More Susceptible to Parental Effects Than Are Others

Several studies have suggested that the relationship between parental care and infants’ attachment depends, at least partly, on the genetic makeup of the child (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2007; Belsky et al., 2007). The most dramatic such effect revealed to date comes from an experiment involving infants who differ in a certain gene that is involved in the manner by which the brain uses the neurotransmitter serotonin.

7

What evidence suggests that some infants are relatively invulnerable to negative effects of insensitive parenting?

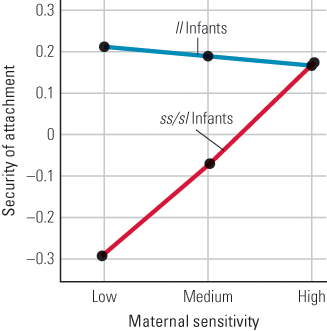

The gene at issue (called the 5-HTTLLPR gene) comes in two forms (or alleles, as defined in Chapter 3), a short (s) form and a long (l) form. The l allele results in greater uptake of serotonin into brain neurons than does the s allele. Previous research had shown that children who are homozygous for the l allele (in other words, have l on both paired chromosomes, as discussed in Chapter 3) are less affected by negative environmental experiences than are other children. For example, they are less likely to become depressed or highly fearful as a result of living in abusive homes (Kaufman et al., 2004, 2006). In the study of attachment, parents were assessed for their level of sensitive care when their infants were 7 months old, and then the infants’ attachment behavior was assessed using the strange-situation test when the infants were 15 months old (Barry et al., 2008). A genetic test revealed that 28 of the 88 infants had the ll genotype, and the rest had either ss or sl.

The results of the study are shown in Figure 12.3. Attachment security increased significantly and rather sharply with increased maternal sensitivity for the ss/sl group, but was not significantly affected by maternal sensitivity for the ll group. The ll infants showed highly secure attachment regardless of the level of maternal sensitivity. Currently much new research centers on this and other relationships between parenting and children’s genetic makeup. It will be interesting to see how such work turns out.

466

High-Quality Day Care Also Correlates with Positive Adjustment

8

What have researchers found about possible developmental effects of day care?

Most studies of attachment have focused on infants’ relationships with mothers, because mothers usually are the primary caregivers to infants. But research has shown that infants can also develop secure attachments with fathers, grandparents, older siblings, and day-care providers (Cox et al., 1992; Goossens & van IJzendoorn, 1990). During the decades after Bowlby and Ainsworth developed their theories, the use of day-care providers increased dramatically. Currently in the United States, roughly 80 percent of preschool children are in some form of day care, usually with caregivers who are not relatives, for an average of 35 hours per week (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Concern about the developmental effects of such care has led to many research studies aimed at correlating variations of day care with children’s subsequent behavioral development.

The results, taken as a whole, suggest that high-quality day care correlates with positive development just as high-quality home care does (Marshall, 2004; NICHD, 2006). High-quality day care is generally defined as that in which children are with the same familiar caregivers each day; the caregivers are warm, sensitive, responsive, and happy; and developmentally appropriate, interesting activities are available to the children. The higher the quality of day care during infancy and toddlerhood, by these measures, the better is the social and academic adjustment of children in their early school years (Hrdy, 2005; Marshall, 2004). Researchers have also found that day care generally does not interfere with the abilities of infants and toddlers to maintain secure attachments with their mothers and fathers, and that parental attachments are better predictors of positive subsequent adjustment than are attachments with day-care providers, regardless of the amount of time spent in day care (Marshall, 2004).

Cross-Cultural Differences in Infant Care

Beliefs and practices regarding infant care vary considerably from culture to culture. Our Western, Euro-American culture is in many ways less indulgent of infants’ desires than are other cultures. Are such differences in care associated with any differences in infant social behavior and subsequent development?

467

Caregiving in Hunter-Gatherer Societies

During the great bulk of our species’ history, our ancestors lived in small groups, made up mostly of close relatives, who survived by gathering and hunting food cooperatively in the forest or savanna. The biological underpinnings of infants’ and caregivers’ behaviors evolved in the context of that way of life. Partly for that reason, an examination of infant care in the few hunter-gatherer cultures that have survived into recent times is of special interest.

9

What observations suggest that hunter-gatherers are highly indulgent toward infants? What parenting styles distinguish the !Kung, Efe, and Aka?

Melvin Konner (1976, 2005, 2010) studied the !Kung San people, who live in the Kalahari region of Botsawana. He observed that !Kung infants spend most of their time during their first year in direct contact with their mothers’ bodies. At night the mother sleeps with the infant, and during the day she carries the infant in a sling at her side. The sling is arranged in such a way that the infant has constant access to the mother’s breast and can nurse at will—which, according to Konner, occurs on average every 15 minutes. The infant’s position also enables the infant to see what the mother sees and in that way to be involved in her activities. When not being held by the mother, the infant is passed around among others, who cuddle, fondle, kiss, and enjoy the baby. According to Konner, the !Kung never leave an infant to cry alone, and usually they detect the distress and begin to comfort the infant before crying even begins.

Studies of other hunter-gatherer cultures have shown a similarly high degree of indulgence toward infants (Lamb & Hewlett, 2005), but the people who provide the care can vary. Among the Efe, who gather and hunt in the Ituri forest of central Africa, infants are in physical contact with their mothers for only about half the day (Ivey Henry et al., 2005; Morelli & Tronick, 1991). During the rest of the day they are in direct contact with other caregivers, including siblings, aunts, and unrelated women. Efe infants nurse at will, not just from their mothers but also from other lactating women in the group. However, at about 8 to 12 months of age—the age at which research in many cultures has shown that attachment strengthens—Efe infants begin to show increased preference for their own mothers. They are less readily comforted by other people and will often reject the breast of another woman and seek the mother’s.

In no culture yet studied is the average father nearly as involved as the average mother in direct care of infants and young children; but, in general, paternal involvement appears to be greater in hunter-gatherer cultures than in agricultural or industrial cultures (Hewlett, 1988). The record on this score seems to be held by the Aka of central Africa, a hunter-gatherer group closely related to the Efe (Hewlett, 1988). Aka fathers have been observed to hold their infants an average of 20 percent of the time during daylight hours and to get up with them frequently at night. Among the Aka, the whole family—mother, father, infant, and other young children—sleep together in the same bed.

Issues of Indulgence, Dependence, and Interdependence

Many books on infant care in our culture (for example, Spock & Rothenberg, 1985) commonly advise that indulgent parenting—including sleeping with infants and offering immediate comfort whenever they cry—can lead infants to become ever more demanding and prevent them from learning to cope with life’s frustrations. Konner (1976, 2010), however, contends that such indulgence among the !Kung does not produce overly demanding and dependent children. Indeed, by all reports, !Kung children are extraordinarily cooperative and brave. In a cross-cultural test, !Kung children older than 4 years explored more and sought their mothers less in a novel environment than did their British counterparts (Blurton-Jones & Konner, 1973).

10

How might indulgence of infants be related to interdependence and to living in extended families?

Some researchers speculate that high indulgence of infants’ desires, coupled with a complete integration of infants and children into the community’s social life, in non-Western societies may foster long-lasting emotional bonds that are stronger than those developed by our Western practices (Rogoff, 2003; Tronick et al., 1992). The result is apparently not dependence, in the sense of fear when alone or inability to function autonomously, but interdependence, in the sense of strong loyalties or feelings of obligation to a particular set of people. In cultures such as the !Kung San and the Efe, where people depend economically throughout their lives on the cooperative efforts of their relatives and other members of their group, such bonds may be more important to each person’s well-being than they are in our mobile society, where the people with whom we interact change as we go from home to school to work, or when we relocate our place of residence from one part of the country to another.

468

In our culture, where nuclear families live in relative isolation from one another, most parents cannot indulge their infants to the degree seen in many other cultures. !Kung mothers are constantly in contact with their young infants, but they are also constantly surrounded by other adults who provide social stimulation and emotional and material support (Konner, 1976). A survey of infant care in 55 cultures in various parts of the world revealed a direct correlation between the degree of indulgence and the number of adults who live communally with the infant (Whiting, 1971). Indulgence is greatest for infants who live in large extended families or close-knit village groups, and least for those who live just with one or both parents.

SECTION REVIEW

Infants develop emotional attachment bonds with the caregivers on whom they depend.

Attachment to Caregivers

- Harlow found that infant monkeys became attached to a cloth surrogate mother but not to a wire one that provided milk.

- Bowlby found that human infants also exhibit attachment behaviors. Such behaviors, which help protect the baby from danger, intensify when the baby can move around on its own.

- Secure attachment of infants to caregivers, measured by the strange-situation test, correlates with the caregiver’s responsive, emotionally sensitive care.

- Infants who have a particular genotype appear to develop secure attachment regardless of the sensitivity or insensitivity of care.

- Secure attachment to caregivers and high-quality day care are both correlated with positive behaviors later in life.

Infant Care in Different Cultures

- Hunter-gatherer societies such as the !Kung treat infants with extraordinary indulgence, keeping them in nearly constant physical contact, permitting nursing at will, and responding quickly to signs of distress.

- The indulgent approach taken by hunter-gatherers appears to produce a strong sense of interdependence and group loyalty, not demanding or overly dependent individuals.